|

Laurence Le Guay - From Fighter Planes to Fashion, Anna Ridley (2002)

Part Three

|

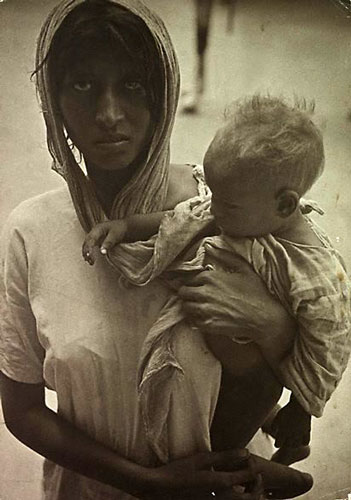

| Indian Woman with child 1943 |

Introduction / Contents / Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 - lists / Part 5 - interview / Main Page

Promoting Photography

"Photography as a new art form with its roots in the twentieth Century, is a correct medium for the representation of contemporary life."35

Even after Contemporary Photography closed down, Le Guay still passionately promoted Australian photography in many ways.

In 1972 David Moore, Wesley Stacey, Daniel Thomas, Peter Keys and Harry Williamson started lobbying the government to set up a national centre for photography. Two years later, they asked Craig McGregor and Laurence Le Guay to join them on the founding committee for the Australian Centre for Photography. They chose Graham Howe as the first director, but after eighteen months he resigned and Le Guay stepped in as acting director.

Through the ACP and other activities, Le Guay promoted photography to the wider world and fought for greater recognition for photographers. He felt that it was very important for photography to be taught properly in universities and art schools, with the greatest emphasis placed on the artistic aspects of the profession. "In photography how the photograph was made...is totally unimportant. It is what the photograph says that is the most important thing. ….I think that photography does not need in the future to worry very much about technique. The camera is going to look after all that, it's going to be so automatic that it is what you are seeing and what you are trying to say that matters much more."36

He was also scathing of the salons in their practice of continually showing the same works by the same photographers. He was particularly annoyed that one image could come to define a photographer through constant hangings in the salons around the world.

Le Guay has always believed that an exhibition should include a selection of a photographer’s work. Of the famous Family of Man Exhibition, in which his one of his works was hung, Le Guay said "The Family of Man indicated a great deal about

Steichen but little about the individual photographers who were mostly represented by a single print."37

He also believed this to be true of photographic publications, and to this end he preferred to choose more works by fewer photographers in each of the Australian Photographic Reviews that he edited. These included Australian Photography 1976 & 1980 and Australian Photography a Contemporary View. He was also an honorary editor of Australian Photography Magazine for many years.

One of the constant irritations that Le Guay had were publishers. These issues started with Contemporary Photography and the battle to get good quality photographic reproductions. This was only partly the publisher's fault as there was a general shortage of quality paper after the war and the costs were high. However, publishers at the time did not think that a photographic magazine was worthy of having time and money spent on its reproductions.

Le Guay spent a lot of time fighting to have better reproductions for his books, especially during the 1960's and 1970's. He was very disappointed with the publication of Sydney Harbour, which was originally intended to be a glossy full colour coffee table book. However, the publishers decided not to spend the money on it and redesigned it as an A4 publication with half the images reproduced in black and white. Afterwards, Le Guay wished that he had never been associated with the project. 38

In his promotion of photography, Le Guay often quoted Susan Sontag in saying that "there is no such thing as good or bad photography, but only more interesting or less interesting".39 This is a maxim he seems to have believed in for sometime and developed more in the later days of his career.

Le Guay firmly believed that photography was a new method of communication and that it could develop its own language, resulting in the photograph being seen as important as the written word. He felt that "because photography today is primarily concerned with visual communication it remains an enigma in traditional art circles. As a new language it has to be learnt like any other."40 "The visual image itself will not need a script and I hope will develop a language of its own with proper guidelines"41 that "is largely what photography is, it's seeing and communicating'42

As an advocator of photography as a visual language and art form, Le Guay was ahead of time and his predictions are now confirmed. Many photographers have benefited from his vision and dedication to the art form, and have a freedom of expression that he pioneered. And how many of us can read the visual more readily than text, as we are now surrounded by images in every facet of life.

|

| Sailing |

After Retirement

In 1970, Le Guay left the studio in the hands of John Nesbitt and David Mist in order to indulge his other passion, sailing. This was prompted by a messy divorce from his wife Ann, who had run off with a good friend of his. The trip was part a desire to get away from all the problems and also as he felt that he had had enough of working life.

He set off around the world on a forty-two-foot steel yacht Eclipse, with three friends and occasionally accompanied by his daughter Melanie, also a photographer. The trip took then from Australia to South Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope and around the Horn to Brazil and then back across the Pacific, the voyage lasting the better part of two years. They also took part in the inaugural Cape Town to Rio race, now a must for serious yachting racers.

While on his voyage, Le Guay sold his share in the studio to David Mist, who continued to run it for another decade. After returning from his sailing trip, and now in retirement, Le Guay undertook a number of projects that he had previously been unable to do.

In 1975 he published his book about his travels on the Eclipse, Sailing Free; Around the World with a Blue Water Australian. He enlisted the help of Olaf Rhuen, a respected travel writer who he had met in New Guinea to put the book in order.

Unfortunately, in 1975 one of Le Guay's twin daughters, Melanie, tragically died in an accident while at the cliffs at Clovelly. Melanie was also a photographer and had started to produce some very good work, more in the style of her father’s early social documentary works and in line with her contemporaries such as Carol Jerrems.

In 1976 Le Guay edited the annual Australian Photography 1976, which brought together all the contemporary Australian photographers of the time. Le Guay used the opportunity to display some of his pet likes, and included much colour photography. He also presented several works of each photographer. In 1978 he edited a similar publication Australian Photography: A Contemporary View and he later edited Australian Photography 1980.

In 1978, Le Guay had a retrospective at the Australian Centre for Photography, including images from all the aspects of his career. During an interview for The Australian, Le Guay said of his work "It's not hard to do. Anyone can do it. I've enjoyed it. But I haven't been the first in anything." 43 The interviewer, Sandra McGrath noted "he may not have been the first, but is certainly one of the best."44

Le Guay also travelled around the top end of Australia and in 1980 published a book on Australian Aboriginals, Shadows in a Landscape. This book and its accompanying exhibition received some attention from the art world, leading Max Dupain to write that "The phenomenon of a top fashion photographer like Le Guay emerging as a champion of Australian Aborigines is interesting and pictorially stimulating."45

He also took on the occasional freelance trip, if the destination was one that was appealing to him. The last of these was to China in 1988 for Vogue. It involved a trip down the Yangtze River, which would have definitely appealed to his adventurous nature.

Le Guay had his boat, Eclipse, moored at Coasters Retreat, Palm Beach and lived on board frequently. He died on the boat on the 2nd February 1990 and a large memorial service was held in a nearby reserve a few weeks later. His daughter Candy still lives at Pittwater and sails Eclipse occasionally.

Conclusion

Laurence Le Guay brought together all the elements of a full and varied career to become one of the leading photographers of his time.

His early work and his relationship with Harold Cazneaux gave him an appreciation of the traditional pictorial style of photography, and this knowledge allowed him to break the conventions with his own work.

His experiences during the war lead to a greater understanding of documentary practice and lead him to promote the documentary on his return. He also gained a love for adventure that was to remain for the rest of life.

He encouraged numerous people in the practice of photography, both amateur and professional, through the pages of Contemporary Photography. He used the magazine to promote the documentary movement in Australia and to fight for the recognition of photography as an art form. He also helped gain better work conditions and pay for many photographers by his promotion of commercial photography.

He promoted photography continually throughout his life, helping to set up the Australian Centre for Photography and being involved in other photography schools. He believed it was essential for photographers here to develop a distinctly Australian style, based on the modernist outlook of the leading European artists. He also believed that photography must taught properly, so that people with an instinct for it could develop the new visual language properly.

Le Guay's biggest contribution was in the area of fashion photography, where he promoted the new and exiting techniques involved in outdoor photography and the use of colour. He used many different forms and styles and happily experimented to keep his practice at the forefront of commercial photography in Australia.

His use of movement, colour and sense of fun kept his images alive and dynamic and perfectly suited the changing lifestyles through the 1950's and 1960's. These new ideas were soon taken up by the raft of new, young commercial photographers who began to appear at the end of the 1960's.

His use of colour and 35mm film in fashion shoots helped to make the new format acceptable to magazines and advertising agencies. The use of 35mm helped to liberate fashion photography from the static set ups required by larger cameras and allowed greater freedom for the photographer.

Although he travelled extensively for fashion shoots and for pleasure, he always felt that Australia was the best place to live. Instead of going overseas to make a name for himself, he preferred to work here and help to promote and further Australian photography.

In all these ways, Le Guay helped to make radical changes in the way fashion was photographed, and this was to the benefit of not only the photographers, but the whole of the Australian fashion industry.

The numerous publications, which he edited or contributed to in later life, played a leading role in helping young photographers to become recognised, and raised their work to artistic status. Without Le Guay, many of these publications would not have happened. He also fought to make these publications the best possible, insisting on quality paper and reproductions to ensure the works were shown to their best advantage.

Le Guay continued to travel, do occasional photographic assignments and promote photography right up to his death.

Although he may not have been the best photographer of his generation (Dupain and Moore were better artists), he was the leader in commercial photography and made the biggest impact on the state of Australian photography through his constant promotion of it.

Laurence Le Guay's tireless work and innovative spirit contributed immeasurably to the Australian photographic industry and helped to gain photography its artistic status. His work and that of his peers allows contemporary photographers to have the freedom of expression that they currently enjoy.

Notes to part two

- 3Laurence Le Guay, Contemporary Photography, Issue 1, pg 7

- Laurence Le Guay, in Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 202

- Laurence Le Guay, Australian Photography; a Contemporary View, pg 5

- Laurence Le Guay, Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 200

- Laurence Le Guay, The Bulletin, April 22 1980, pg 88 and Australian Photography; a Contemporary View, pg 5

- Laurence Le Guay, Happy Snaps and Snippets, pg 1

- Laurence Le Guay, Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 186

- Laurence Le Guay, Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 190

- Laurence Le Guay, in Sandra McGrath, The Australian, 13th March 1978, pg 8

- Sandra McGrath, The Australian, 13th March 1978, pg 8

- Max Dupain, The Sydney Morning Herald, 28th February 1980, pg 8

Introduction / Contents / Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 - lists / Part 5 - interview / Main Page

|