Laurence Le Guay - From Fighter Planes to Fashion, Anna Ridley (2002)

Part One

|

| Dance Movement 1946 |

Introduction / Contents / Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 - lists / Part 5 - interview / Main Page

Background - Photography in Australia

Photography came to Australia in 1841 when a Frenchman, Captain Lucas, demonstrated the daguerreotype process in Sydney. In 1942, George Barron Goodman arrived from England and became the first professional photographer. Photography soon began to spread around the colonies and various photographic studios, mostly dedicated to portraiture, were opened.

By the late 1850's, photography was widespread and the photographers were allowed to exhibit at the Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts in Australia, giving them their taste of artistic status.

Photography was also being used as a scientific tool, to record fossil finds and geological structures, and by the government, to record the growth of the colonies and to survey the surrounding lands.

In the 1870's Henry Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss began touring the cities and country areas to take views and portraits of the locals. These were favourably received and usually included the family in front of their business or house. They also spent a large amount of time photographing all the important buildings in Sydney, images that they later sold as tourist style postcards to people in the country.

In the 1890's amateur photographers started to form photographic societies and the numbers of amateur photographers swelled accordingly. Several important photographers began working around this time, including Paul Folsche who photographed many areas of the Northern Territory and completed many studies of the aboriginal population.

Press photography started in the 1900's with the mainstream introduction of the halftone printing process (developed in the 1880's) that allowed photographic images to be reproduced on the same page as text. This led to most of the major newspapers employing photographers by 1910.

During the 1920's and 1930's the press photograph gave a distinctly nationalist view of Australia. These images were used to spread the nationalistic fervour brought on by federation and to encourage people during the depression years. The press also developed a basic documentary style, which was to evolve rapidly several decades later.

The 1920's saw the new German photography emerge in Europe, with practitioners such as Man Ray, Laszio Maholy-Nagy and Hebert Bayer experimenting with new forms and subjects. This style of photography became known in Australia during the 1930's and several practitioners here, such as Max Dupain, adapted it to great effect.

During the 1930's new areas of business also opened up for the professional photographer. Advertising, fashion and industrial commissions were adding to the stock in trade of portraiture. This subject matter was seen as ideal for the new aesthetic of sharp lines and focus and clear detail. Colour photography also became commercially available during the 1930's and was to add to the new aesthetic being developed.

This was the new world of photography that was to be the breeding ground for some of Australia's best photographers, including Max Dupain, Damien Parer, David Moore and Laurence Le Guay.

.

Laurence Craddock Le Guay

"I hesitate to call the practice of photography a profession ...I encounter odd pangs of guilt that I have never done a day's work in my life"1

Laurence Le Guay was born in Sydney on the 25th December 1916. His Grandfather was a sea captain from Jersey in the Channel Islands who migrated to Kurraba Point in Sydney in the 1850's.

Laurence grew up around Sydney Harbour, living on both the North Shore and in the Eastern Suburbs. He learnt to sail at early age, a passion that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Le Guay's interest in photography began while he was at school. He took a camera on most holidays and outings, and started to learn the technical aspects of photography. His mother was somewhat displeased when he began to develop his photographs in the family bathroom. 2

He bought all the books he could and was thrilled to meet and be taught by Harold Cazneaux. Cazneaux fostered his interest in photography further and helped Le Guay to learn some of the tricks of the trade. He also encouraged him to start a career in photography.

In 1935 Le Guay began as an assistant at Dayne Studios. They produced fairly standard portraiture and Le Guay soon grew dissatisfied with this type of work. He felt that he was entering a profession that was taking on the challenges of the new and the modern and saw no reason to stay behind doing portrait work. Le Guay always had a love of the new, so new technology and creative ideas held a special appeal for him.

In order to take up the kind of work that would be challenging he and a friend, John Nisbett, opened their own studio at 17 Martin Place in 1937. Aged only 20, Le Guay began to specialize in the illustrative and fashion photography that would make him famous. To start the studio off, they also did society portraiture and weddings.

At this time, he also began exhibiting at the various national photographic salons. Le Guay did not much like the Salons, but this would have been a way to get himself noticed and accepted by the acknowledged experts of the era. His Symphony in Grey (Plate 1 unavailable) entered in the 1937 Victorian Salon shows his use of form and design to lift the image out of the ordinary, which contrasted markedly with the pictorial style still dominant in the salons.

He also joined the Sydney Camera Circle, which was by then already past its glory days. Harold Cazneaux, Cecil Bostock, James Stenning and James Paton had formed the Camera Circle in 1916. The Circle members aimed to pull pictorialism out of the shadows and halftones and into the sunlight of the Australian environment. At the time, this was a major change from the European form of pictorialism and would help with the progression of modernism in Australia.

However, like Max Dupain and David Moore, Le Guay took a much more distinctly modernist approach to photography and he did not endear himself to some of the older members of the circle.

For the Sesquicentenary in 1938, the photographic societies organised an international salon which they declared "The finest exhibition of modern photography ever displayed in Australia."3 However, Max Dupain and the other young modernists felt that the exhibition was lacking in contemporary photography and that it still retained too many pictorialist elements.

In reaction to the salon, Max Dupain and several other prominent photographers formed the Contemporary Camera Groupe. 4 They rebelled against the predominate pictorial style of the time to allow more modern work to be considered as artistic.

Interesting, the Groupe contained the pictorialists Harold Cazneaux and Cecil Bostock, as well as photographic illustrators such as Le Guay and Russell Roberts. Although the Groupe only lasted a year and only had one exhibition, they did succeed in changing the views of modern photography then held by many in the photographic world.

One review of the time noted "Lawrence (sic) Le Guay presents some highly interesting and attractive compositions, notably "Metamorphosis" (a face in double exposure) and the "The Life Saver". In "Yesterday" a study of an old wheel, he shows brilliantly the significance which can lie in simple things." Another reviewer felt that "Mr. Le Guay has in the past been disposed to a reckless bravura. Now, he has organised some good qualities, and in "Still Life" and "Street Scene" there is a note of sincerity."5

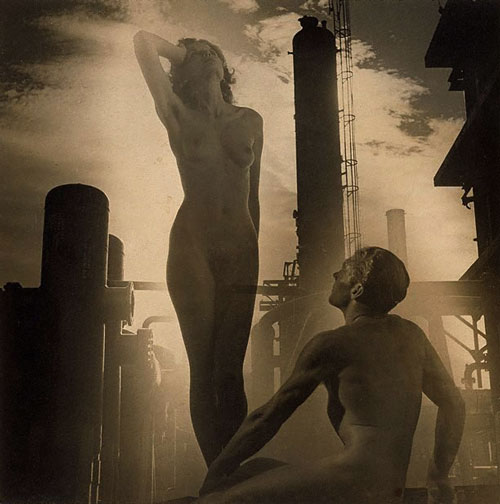

Le Guay's work was influenced by the new ideas emerging in overseas photography. Style and subject at this time was linked to ideas of modernism and machinery, complemented by images of humans and humanity. Along with Max Dupain, he experimented with montages of bodies and machinery or images of war to gain a surrealist effect that implied the conflict of man and machine.

One such image was The Progenitors (plate 2), which uses themes of man versus machine and human reproduction. A man gazes up at a woman who is in turn looking to the heavens, both are nude. This image is superimposed over a photograph of a factory, implying the battle that man has with machine and his supremacy over machines. The image also implies humanity and the divine right of man to conquer the world and reproduce as needed.

One of his most famous montage images at the time was used as a poster to promote the war and recruiting (plate 3). However, it was quickly recalled when people realised it had an anti-war effect with its depiction of a beautiful yet sad women and a child playing with toy submarine and soldiers. This image was super-imposed over newspaper headlines that announce missing or sunken submarines, giving a sense of the loss that war can bring. |

|

|

| |

#2 The Progenitors 1938 Art Gallery of NSW |

| |

|

| |

|

#3 War Poster 1938, Art Gallery of NSW |

.

World War II

Despite his ambiguous attitude towards the war seen in his montages, Le Guay closed his studio in October 1940 when he enlisted in the RAAF for the duration of World War II. His partner, John Nisbett also joined the RAAF and was sent to New Guinea.

Le Guay tells a story of how a big wedding assignment went wrong and all the films were ruined. As a consequence, the next day they closed the studio and enlisted in order to escape the bride's father.6 However, like many other young men, Le Guay had a well-developed sense of adventure and it is more likely that he enlisted due to a desire to see some of the world and have a bit of fun.

After training at Richmond, he was sent to the 451 Squadron in February 1941 as a photographer. He was posted to the Middle East and served in the Western Dessert, Tobruk and Cyprus. His assignments depicted the troops at work on the ground and in the air, and he also did many formal group photographs of the various officers and flight crews.

In July 1943 he was transferred to the RAAF liaison office in the Middle East and undertook assignments for the Public Relations section. These assignments sent him all around the Middle East, Italy, England and Eastern Europe. In December 1943 he was given a Flying Officers commission in the Administration and Special Duties branch and continued service with the Liaison Office until January 1946.

Over four thousand of Le Guay's war photographs are held at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. There is also a reel of German training film that Le Guay and his team found in a captured German bunker, and which he later donated to the museum.

One of the most personal and poignant images is of Pope Pius XII greeting soldiers in Rome in 1944 (plate 4). Le Guay recalls, "When the Allies entered Rome during World War II, Pope Pius granted an audience to some of the victorious troops.

I was lucky enough to grab this in the small audience chamber before being hustled out by the Swiss Guards".7 The image shows the emotion of the soldiers in meeting the Pope and the gratitude of the Pope for the work of the soldiers in liberating Rome. It also conveys a sense of the impact of war in the soldier's lives and the relief in having won such a victory.

A service report by the Air Force in 1944 notes that Le Guay "stands out in the performance of his duties" but "does not organise things very well" His Senior Officer also notes that "Le Guay is an exceptionally good photographer from the technical angle, but his knowledge of pure press photography is immature. He is more attracted to the art side than to the news side of his trade."8

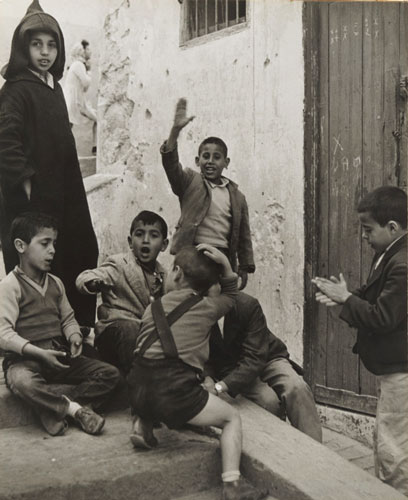

While he may not have had a good knowledge of "pure press photography", the documentary images that Le Guay took while working for the RAAF stand out as examples of social realist photography. Le Guay was taking personal photographs of the civilians affected by the war, which depicted the hardships and trauma suffered by the women and children whose husbands and fathers were fighting in the war.

These images, such as Children of Tangiers (plate 5), show Le Guay's documentary sensibilities as well as his personal reaction to the war. These images would not have been welcomed by the RAAF as they were clearly styled to show the social realities of the war and its effects on ordinary people.

Le Guay did not use this documentary style after the war, however his war experiences made him sympathetic to the documentary and social realist photographers and he always remained on good terms with them. |

|

|

| |

#4 Pope Pius XII, Rome c1944, Art Gallery of NSW |

| |

|

| |

|

#5 Children of Tangiers,c1943 National Gallery of Australia |

.

Post War Freelancing

After demobbing, Le Guay spent some time in England working at the photographic studio of a London fashion magazine. In 1947, Le Guay opened a studio with Hal Missingham in Lower George St, calling themselves the Society of Realist Art.9 Unfortunately, there was an explosion and fire not long after they started operating and the two of them went separate ways. Le Guay did freelancing work for several years before returning to set up a new studio with John Nisbett in premises on Castlereagh Street.

According to Gael Newton in Silver and Grey, Le Guay made a film of the Harbour Bridge in late 1947. No other record of this film has been found.10 However, if this information is correct, it shows that Le Guay was experimenting with other forms of creativity at this time. In 1967, Le Guay admitted that he had dabbled with some painting, however other forms of creativity where never as important to Le Guay when compared to his photography.11

One of Le Guay's early freelance assignments was for the newly formed Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions. The expedition was primarily undertaken for scientific research and the mapping of the Antarctic. Phillip Law, the chief scientific officer, noted that Le Guay was a very handy member of the crew and proved to be a great wit.12

The expedition left Australia in early 1948 on the HMAS Wyatt Earp, intending to land at Mawson's old base in Commonwealth Bay. However, the pack ice was too thick and they were forced to survey the Balleny Islands further to the east. As the official photographer for the Department of Information, Le Guay took photographs of the landing party going ashore and of various other aspects of the voyage.

One image of the landing party going ashore (Plate 6) shows the harsh conditions of the Antarctic and the primitive equipment available to the explorers in those times. The image is a very dynamic one, and shows the power the men had to use in order to row ashore. As a close-up image of the men, it is atypical of most of Le Guay's Antarctic work, the majority of which show the landscape or figures at a distance involved in the scientific research. These images are now held at the Australian Antarctic Division in Hobart.

The expedition to Antarctica lasted eight months, and on his return Le Guay spent several years doing assignments for the National Geographic in outback Australia, including Cape York, the Gulf of Carpentaria and the Barrier Reef as well as in remote locations overseas.

Sir Edward Halstrom commissioned another major freelance trip to the highlands of New Guinea where he owned land. On this assignment Le Guay took what is possibly his most famous non-fashion image, the Kanama Ceremony (plate 7).

This image depicts an intimate mating ritual among young New Guinea boys and girls, where they rub noses and cheeks with each other. A sense of the couple's awkwardness in the ritual and the obvious importance of the ritual to the tribe can be clearly seen in the image. This ceremony had not been documented before, nor indeed many of the highland areas where few white people went. The photograph was one of two Australian images which were later included in Steichen's Family of Man exhibition in New York.

After several years of doing these assignments, Le Guay returned to the work of the studio. He and John Nesbitt reformed their partnership and set their new studio up at 148 Castlereagh Street. This partnership was to last until 1972. He was still able to travel overseas for location shooting, but from 1950 until his retirement, he devoted himself exclusively to fashion photography, commercial illustration and other portraiture work. |

|

|

| |

#6 Landing Party, Belleny Islands 1948, Antarctic

Scanned photocopy - higher quality photo unavailable

|

| |

|

| |

|

#7 Kanama Ceremony, New Guinea c 1948 National Gallery of Australia |

Notes to part one

- Laurence Le Guay, Sailing Free; Around the World with a Bluewater Australian, pg 9 -11

- Laurence Le Guay, in Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 178

- Gael Newton. Shades of Light pg 112

- The Contemporary Camera Groupe Members: Cecil Bostock, Harold Cazneaux, Russell Roberts, Max Dupain, William G. Buckle, George J. Morris, Douglas Annand, A. E. Dodd, Louis Witts, Olive Cotton, Damien Parer and Laurence Le Guay.

- Both Quotes from clippings in the AGNSW Library file, Authors and Publications unknown, 1938

- Laurence Le Guay, in Kevin Aston, Australian Photography, March 1967, pg 23

- Laurence Le Guay, Happy Snaps and Snippets, pg 2

- RAAF Service Report, Australian National Archives Canberra

- Laurence Le Guay in Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 181

- Gael Newton, Silver & Grey, unpaginated

- Laurence Le Guay, in Kevin Aston, Australian Photography, March 1967 pg 22

- Phillip Law, 7"he Antarctic Voyage of HMAS Wyatt Earp, pg 43

Introduction / Contents / Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 - lists / Part 5 - interview / Main Page

|