Laurence Le Guay - From Fighter Planes to Fashion, Anna Ridley (2002) Part Two  | | Fashion Illustration 1948 |

Introduction / Contents / Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 - lists / Part 5 - interview / Main Page

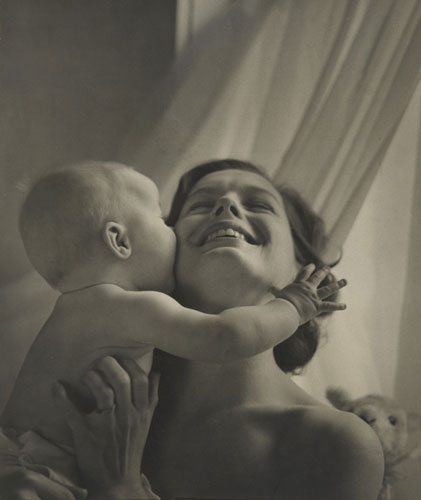

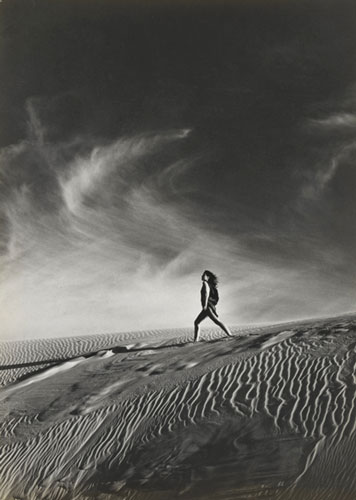

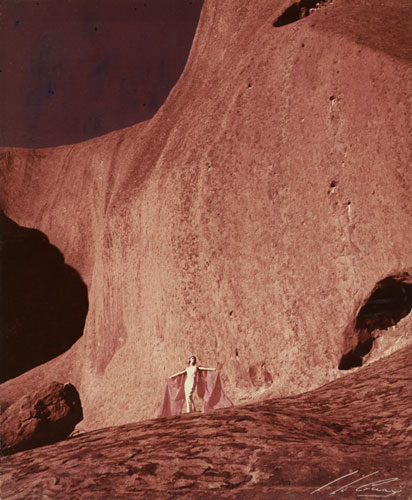

Contemporary Photography Magazine and The Australian Documentary Movement "Contemporary Photography will welcome from photographers, any comments or articles, no matter how controversial their subject, which attempt to improve the status of photography as an art, a science or a casual hobby"13 In 1946 Le Guay founded Contemporary Photography Magazine. The magazine was the first photographic publication in, Australia not funded by one of the photographic supply companies. This helped to guarantee its independence and kept it free from the advertorial style of previous publications. Le Guay allowed much space for the new and the different in the magazine. He published without favour or prejudice, giving equal time to both professionals and amateurs. He reproduced the works of Harold Cazneaux and Max Dupain (among others), alongside that of enthusiastic amateurs, giving both the same level criticism and encouragement. He gave special room to Harold Cazneaux, his mentor, and reproduced many of his works from the earlier part of the century. These were re-interpreted in a documentary way, and gave inspiration to another generation of photographers. Le Guay always called on photographers to challenge themselves artistically and to express their personal creativeness. In his love of all things new and modern, Le Guay promoted the new styles of photography that were emerging overseas. He published many examples of the work of Horst, Beaton and others with praise, and the exhortation that Australian photographers needed to follow and adapt the modern styles being pioneered overseas. He tried to foster an Australian style in photography, based on the new techniques emerging from overseas, but rendered in a uniquely Australian way. The documentary was given life in the magazine and made much of the works of Max Dupain, David Moore and Axel Poignant among others. These photographers and others established the documentary tradition in Australia through the pages of Contemporary Photography and helped a new generation of photographers to work in the social realist mode. Along with Geoffrey Powell, Edward Cranstone and David Moore, Le Guay was one of a group of post war photographers who called for photography with a social conscience. Although Le Guay had produced strong documentary work during the war, on his return he did not actively pursue the documentary style. He mainly used the documentary style as backgrounds for his fashion images, photographing models in front of slum dwellings, and found that the contrast in the glamour of the fashion to the squalor of the surroundings worked well visually. However, Le Guay was happy to promote the documentary in the pages of Contemporary Photography Magazine. He gave space to the documentary photographers and helped to bring many of them, such as Geoffrey Powell, into prominence. According to Anne-Marie Willis in Picturing Australia, Le Guay's interest in the documentary occurred because "it challenged the gentle pictorialism still prevalent in camera club photography. The documentary philosophy produced "new, exciting" subject matter."14 This reflects Le Guay's interest in the new and the challenging and anything that was totally opposite in style to the salon type images that he disliked. Le Guay himself said in an editorial "If the photographer is sincere in his attempt to document contemporary life with honesty and sufficient understanding - if he can read and translate the fear, love, hatred and humour of life into an art form which will live and can be readily understood, he can present a challenge to many of the petty values so evident in much of present-day art and photo-pictorialism. "15 Although he gave space to many photographers with many different images, Le Guay was also quite harsh when it came to reproducing works. David Moore's famous image, Redfern Interior 1949, was cut in half by Le Guay as he felt that it had more impact that way. Very few photographers dared to complain about this treatment of their works, both because Le Guay could quite intimidating and as it was common for editors to have this kind of artistic control in that period. While he had exhibited regularly in the salons in his early years, Le Guay now attacked them periodically through Contemporary Photography. In an editorial he stated that "In the average Salon there are still too many landscapes, too many portraits and too few glimpses of reality through the personal interpretation of the photographer."16 Le Guay felt that the Salons were not encouraging new work and were stuck in the traditions of the pictorial movement that was now losing its dominance in other areas of the profession. As time went on, Contemporary Photography became more oriented towards commercial photography. Le Guay and many other photographers made their livings through commercial work, and few had the luxury of time to allow the production of personal images. Le Guay wrote many editorials in support of the commercial photographer and called for higher rates of pay and greater recognition of the photo-illustrator as distinct from the studio photographer. The magazine eventually became the official publication of the Professional Photographers Association of Australia, of which Le Guay was not actually a member.17 Le Guay edited and produced the magazine for around five years, although the fire at his studio destroyed many submitted images and interrupted the magazine for several months in 1947, Le Guay eventually had to finish with the magazine as his attempts to find someone else to run it had failed. He was under increasing pressure with his studio work and he found he had limited time and a lack of support in the running of the magazine. The magazine had proved to be an important focus for photographers during its time, and through it Le Guay helped to encourage and inspire many new practitioners. Fashion Illustration "Of all the qualities and talents that go into the making of a first-rate photographer, I believe that taste is the most essential. Without taste, technical brilliance and imagination are useless. Without taste, energy and drive are wasted. Without taste, experience becomes a rut. "18 The studio which Le Guay and John Nisbett had set up in 1938 specialised in photographic illustration and fashion photography. Le Guay did most of the photographic work, while Nisbett keep the studio running and dealt with the business aspects of the partnership. Even though he was so heavily involved with Contemporary Photography and the promotion of photography, to Le Guay fashion and commercial illustration were always the most important part of his photographic career. As in other areas of his work, Le Guay was never a conventional fashion photographer. He felt that traditional fashion photography was too staid and rigid, so he took a pro-active approach and started to change the way in which models and clothes were captured on film. In the early days of fashion photography, the photographers were competing with fashion illustrations in the magazines. Many editors and retailers were happy to introduce photography into their publications, but alongside the more traditional drawings. Because of this, the photographers tended to follow the style of the illustrations in their image design. The models were often posed standing in simple, subdued manner, set in elegant rooms or the studio. In the 1930's fashion photography started to change from the placid poses of models to more dramatic poses, with close-ups and angles being a feature. The studio of Russell Roberts in Melbourne was a noted leader in this new form of fashion photography. Models were also starting to be photographed outside the studio, although the outdoors was not allowed to intrude upon the model or the clothes. The changes in fashion photography mirrored the changes in fashion itself. Dior's 'New Look' gowns in the late 1940's was perfectly matched by the glamorous studio photography that usually used famous movie or stage actresses as models. Athol Shmith in Melbourne used this technique to great advantage in very formal portraiture to enhance the glamour look that every housewife dreamed of. The 1950's saw fashion photography once again move out of the studio and onto the streets, this time with the setting playing more of an important role in the image. However, many of the retailers and editors did not find this type of creative photography so pleasing and the photographers were forced to continue with more traditional poses. They faced an uphill battle to get creative photographs of the creative clothes that would not be won until well into the 1960's. During the 1950's Le Guay, like many photographers, used a mix of the classical portraiture style and the newer outdoor style. Affection, Mother & Child (plate 8) shows the more formal style of photography that Le Guay used in the early days. He often did society and wedding portraits, and it is likely that this was a private commission rather than a fashion image. However, the work demonstrates the power that Le Guay could give to an image, as the bond and love between the pair shine out of the work. The visible joy of the mother is lifted further by the light entering from the right-hand side. In 1951, Le Guay's wife Ann gave birth to twin daughters, Melanie and Candy. In Affection, Mother & Child Le Guay is possibly expressing some of his newfound fatherhood instincts. Le Guay did many nudes during the late 1950's and early 1960's, photographing them for K.G Murray's Men Only publication. However, they were always the tasteful, almost pictorial nudes that the period required and not in any way related to the style now seen in many men’s magazines. Examples of these can be seen in the Powerhouse Museum collection. A typical fashion illustration from the late 1950's is one that Le Guay took on a visit to Hollywood (plate 9). In some ways this image goes back to his earlier 1940's images contrasting glamour clothing with the Sydney slums. The image places the model in a street scene, with a large movie light on the right-hand side. The effect intended is that of a movie set, and the model in her fabulous dress clearly stands out as though she were not quite in the right world. This only serves to place more focus on the model, despite the crowded scene. | |  | | | #8 Affection, Mother & Child c1955 National Gallery of Australia | | |  | | | | #9 Fashion Illustration (Hollywood) late 1950s, Art Gallery of NSW | To help creative commercial photography became more widespread and acceptable, the Professional Photographers Association was formed. David Mist and David Moore were both members, however Le Guay did not join. He did allow them the use of Contemporary Photography to promote themselves and Le Guay used editorials to call for better conditions and rates of pay for professional photographers. Along with Rob Hiller and Ray Leighton, Le Guay and John Nisbett were two of the pioneers of movement that worked towards using outdoor locations. They tried to make the setting and the clothes work together to show off both to the best advantage. When placing his models outdoors, Le Guay used naturalistic poses and angles that highlighted the idea of the clothes rather than directly showing off the clothes. This was early kind of lifestyle photography, where the models were carefree and the clothes formed part of an overall way of living. In this way, Le Guay had an impact on fashion photography, liberating it with the use of movement, colour and a sense of fun not seen before. In 1956, Le Guay shot the cover photograph for the first issue of Vogue Australia magazine. It was a very Australian image of a swim-suited model on the beach. This was a supplement that went with English Vogue and was available quarterly. Along with Flair magazine, Vogue was one a few magazines in Australia that was interested in any sort of outdoor settings. They were after an Australian feel for the new supplement, and Le Guay's work fit in very well. However, the major retail stores, such as David Jones and Farmers and the major advertising agencies were not yet accepting of the changing trends. It took until the 1960's for this type of photography to become accepted by the agencies, some magazines and retailers. In setting his models outdoors, Le Guay used many different styles. He posed models walking over sand dunes or lying in the park. He used movement by the models to give the clothes more power or set the models in unexpected locations. One such image shows a model walking across a huge sand dune at Cronulla (plate 10). The sheer scale of the dunes totally overwhelms the model, and the clothes she is wearing are almost unrecognisable. However, the scale adds power to the image, and the viewer is forced to give attention to the model. The image sells the clothes through the use of feeling and the idea that anyone could end up in this remote looking landscape just by wearing the clothes. It is also a very Australian image, with the endless sky and vast amount of sand. Le Guay also used scale within the camera to give the impact to one of his most powerful images, an advertisement for Courtaulds Fabrics shot at Uluru (plate 11). Placing the model in front of rich orange/red of Uluru gave contrast to the pink colour of the dress and helped to give a feeling of an otherworldly place. This otherworldly feeling is evident in much of Le Guay's fashion work, and is perhaps the only consistency within his works. The image also shows off the dramatic colours of the Australian landscape and Le Guay loved to use colour as often as possible. All these elements combined to give a greater impact both to the clothes and to the model herself. Le Guay had a great sense of fun in his fashion work, and his most famous fashion image reflects this. Fashion Queue 1960 (plate 12), shows the models posed in amongst the regular travellers at a bus queue, with two young boys in masks running around them. The models are very formally dressed and posed, including the wearing of hats and gloves. The men in the queue are not paying any attention to the models or the boys, one reading his paper and the other looking for the bus. The action of the boys and the reaction of the model on the right prevent the image from being to static, while adding an element of frivolity to the scene. This image shows the progressive ideas that Le Guay used to bring something unique and fun to his work. Le Guay also used cheekily different poses to give a point of difference to his images. A great example has the model posed next to a kitsch sculpture of an Indian Brave (plate 13) mocking the pose of the sculpture. The whole look is fun, cheeky and very effective. The clothes are still the feature, but the image takes a somewhat ordinary outfit and gives it a new attitude. In the early 1960's Le Guay and Nisbett invited a young English photographer, David Mist, to join them as a partner in the studio. According to Mist, one of Le Guay's main attributes as a photographer was his willingness to experiment.19 | |  | | | #10 Fashion Illustration, Cronulla Sand Dunes NGA | | |  | | | | #11 Fashion for Courtauld Fabrics, c1960 NGA |  | | #12 Fashion Queue 1960, Art Gallery of NSW | | | | |  | | #13 Fashion Illustration c1967 from Australian Photography, March 1967 pg 23 Scanned photocopy - high quality photo unavailable | Le Guay used different forms of image manipulation, including darkroom work and in camera manipulation to create different effects in his images. "He enjoyed going into the darkroom and getting ferrous cyanide and running it all across the picture and seeing what he could do, he was an experimenter... He'd play around and experiment and break all the rules, which was just as well."20 Kevin Aston, a photographer who wrote for Australian Photography noted that, "Le Guay's forward looking approach, perhaps even more than his talent, has surely kept him in the forefront of commercial photography in Australia"21 Of his work in fashion and about photography in general, Le Guay said "We must be prepared to experiment to some degree, and now and then, be prepared to break away from approved concepts or run the risk of becoming stale."22 "This is easily the most exciting and freest time for photographers. You can innovate. You must."23 One example of this type of experimentation is a fashion illustration from 1976 (plate 14). Le Guay either covered his camera lens with water droplets before shooting the image, or gave it a watermarked appearance in the darkroom. However it was manipulated, the effect is striking, with the vivid colours and watermark patterns helping to focus attention on the model and her clothes. There are also other examples of Le Guay manipulating images during printing to give a better effect. He did a series of fashion illustrations in London in the late 1960's where he elongated the image during printing to give the model more height and a greater impact in the image. | |  | | | | #14 Fashion Illustration 1950s, Art Gallery of NSW | Le Guay did many fashion shoots overseas, in places such as England, Spain, Tahiti, as well as other exotic locations and all over Australia. He used these assignments as a way to indulge his adventurous nature and get free travel. According to David Mist "He was a wizard at putting together trips...could always work a deal for a free airline ticket to get him somewhere... which in those days was quite hard to do."24 One factor that frustrated Le Guay was the limitations of the large format cameras. David Mist explains "a lot of the agencies and a lot of the retailers, would not accept 35mm, you had to use large format and in a lot of cases it was 5x4."25 Le Guay felt that the "miniature" camera, as it was known, could produce just as good results as the large format and was much easier to cart around. When 35mm did become acceptable for publications, it allowed the photographer much greater freedom as they could walk around the shoot and get a greater variety of angles and close-ups much more easily than before. In 1978, Le Guay was happy to note that "Fashion Photography... is at last being recognised with some interesting exhibitions overseas as an integral element in photographic sociology."26 Le Guay made one other important contribution to the Australian fashion industry from the 1950's to the 1970's. He had close ties with the famous Eileen Ford modelling agency in New York, and would send them pictures of the Australian models that he thought were the best. These models were often picked up by the Ford Agency who would fly them to New York to model. Many girls made their names and fortunes this way, including Margot McKendry and Jean Newington.27 This was important to the models, as there was not much money to be made from modelling Australia at that time. Le Guay was awarded an Australian Photographic Society Commonwealth Medal in 1963 for "his contributions to the professional fields and through the continued high standards of his personal work, his published papers, lectures, editorial contributions and work for professional organizations in Australia."28 He was also a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and an EFIAP. Colour Photography "Why, when everything out there is in colour do they insist on reducing the world to black and white?"29 Colour photography began in Australia with the advent of the additive screen plate process in the 1900's, mainly used for the production of transparencies. Autochrome plates followed quickly, these gave a slightly pointillist effect and were embraced by the amateurs in the photographic clubs as an ideal technique for pictorialist images. However, it was during the 1930's when colour photography really made its mark in Australian photography. Dufaycolour was the first roll film available in colour and allowed the amateur to easily reproduce colour transparencies with use of basic box brownie camera. Kodachrome, developed at the end of the 1930's, gave an even better colour result and by the end of World War II it had become the film of choice for serious amateurs and professionals. After the war, Le Guay embraced colour photography with a passion. This may have just been his way of staying ahead of the pack but it certainly acknowledges his love for the new and the progressive. Some early images were captured while still in Europe and he had access to colour film. Le Guay said, "we should be demanding and searching more and more for the total use of colour."30 He felt that there was no reason to photograph in black and white unless the situation was so dark or lacking in colour that it made the use of colour redundant. Of his Kanama Ceremony (plate 7) photograph, he said "There was no possibility there, if you used available light, of getting any image at all in colour... The people were black, and the surroundings were black... If they'd had a lot of bright colours on, I'd be rather arguing that I shouldn't have attempted to do it in black and white, because it didn't show the colours, which would have been part of their make up."31 In this he acknowledged that colour wasn't always appropriate, and that black and white still had its uses. However, he felt that many of the black and white images on show in exhibitions around the world would have benefited from being colour instead. He did not mean that everything had to be bright and brazen, indeed of colour he said "It needs to be toned down, it needs to be reduced in colour contrast, an aid to the image in every way. It doesn't need to be blatant except in exceptional circumstances."32 For the 1978 retrospective of Le Guay's work, Nancy Borlase noted "A majority of colour prints reflect Le Guay's current interest in the increasing hegemony of colour over black and white. Some of his most brilliant action snaps, taken at the bullring or racecourse, are in a saturated monochromatic range"33 Unfortunately, Le Guay often could not use colour film as it was very difficult to get up until the late 1960's. Kodak Eastman only imported the film in small amounts and there were few places that could develop it. The demands of the fashion magazines for large format film also limited the use of colour, which was often only available in 35mm format. Le Guay also loved to experiment with colour. "We are just beginning to enjoy ignoring the admonitions of the manufacturers and to find a whole new world of imagination by using the wrong exposure, the wrong colour temperature old uncorrected lenses, or maybe outdoor colour films with floodlights and vice-versa."34 Some of his more experimental colour images were of sail boats, where he enlarged the negatives so much that the grain stood out clearly, giving a soft pointillist effect to the water and sails. Le Guay's persistence with colour certainly paid off in the end, as magazines and editors came to embrace it Le Guay and his partners were at the forefront of colour fashion and commercial photography.

Notes to part two - Laurence Le Guay, Contemporary Photography, Jan-Feb 1947, pg 7

- Anne Marie Willis, Picturing Australia, pg 193

- Laurence Le Guay, Contemporary Photography, May - June 1947, pg 7

- Laurence Le Guay. Contemporary Photography, Issue 3 March 1947, pg 9

- See Appendix 3, Interview with David Mist pg 5

- Laurence Le Guay, in Kevin Aston, Australian Photography, March 1967, pg 21

- See Appendix 3, Interview with David Mist pg 3

- See Appendix 3, Interview with David Mist pg 3

- Kevin Aston, Australian Photography, March 1967, pg 25

- Laurence Le Guay, in Kevin Aston, Australian Photography, March 1967, pg 24

- Laurence Le Guay, in Gavin Souter, The Sydney Morning Herald, 26th August 1966, pg unknown

- See Appendix 3, Interview with David Mist, pg 3

- See Appendix 3, Interview with David Mist, pg 4

- Laurence LE Guay, Australian Photography, A Contemporary View, pg 5

- See Appendix 3, Interview with David Mist, pg 6

- Australian Photography 1976, dust jacket notes

- Laurence Le Guay, in Sandra McGrath, The Australian, 13th March 1978, pg 8

- Laurence Le Guay. Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 187

- Laurence Le Guay, Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 187

- Laurence Le Guay, Interview with Hazel De Burg, pg 187

- Nancy Borlase, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 March 1978, pg 16

- Laurence Le Guay, in Kevin Aston, Australian Photography, March 1967, pg 25

Introduction / Contents / Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 - lists / Part 5 - interview / Main Page

|