|

cover & contents page | Rise & Fall of Kerry & Co | The Man & The Photographer | The Collection | The Plates | Biography | Kerry page

Charles Kerry, the collection

The collapse of the Kerry photographic business in the 1920s made the firm's enormous plate glass collection redundant. A mere fragment of what must have been a large depository then resided for many years in Tyrrell's Bookshop at Crows Nest, in Sydney.

It had been bought by the grandfather of the present owner, W. T. Tyrrell, when the bookshop was sited in George Street, only a few hundred metres from Kerry's offices at 308 George Street. In 1980 this collection was sold to Consolidated Press Holdings Ltd, Sydney. The greater proportion – ninety per cent – is made up of 10 cm x 8 cm dry plate negatives, used for the postcard business. There are also a few boxes of 25 cm x 20 cm negatives. The quality of the 25 cm x 20 cm images is generally superior to that of the smaller plates.

Together they are a mere fragment of the large business Kerry established in the rural areas of New South Wales and Queensland, when graziers, stud owners and engineering interests commissioned his firm to record their farms, their geldings and their artesian bores. There are also a few studio portraits, ranging from sensitive pictures of attractive or striking women to boxes of very dull, mechanical portraits of young men in khaki about to sail for the Dardanelles, Palestine and the Somme.

|

Wedding Group

|

A few miscellaneous items, such as stereoscopic views, plates of greeting cards garnished with artwork, and a handful of gelatin panoramic negatives complete a collection of about 7,000 items.

When these negatives were sorted through as part of the selection for this book and exhibition, some dominant themes emerged. These were confirmed by reference to Kerry & Co.'s sales lists which give full descriptions of the firm's stock in postcards and photographs.

The subject matters preferred by Kerry & Co. and appreciated by the public fall into neat categories – scenic views of New South Wales, New Zealand and Queensland, views -of country towns, downtown Sydney, Aborigines, rural life, native flora and fauna, sentimental genre and a few items of current interest, notably the Federation festivities.

To turn to the scenic views first. By the time Edward VII was on the throne, eastern Australia was served by a network of railways radiating from the three state capitals into the bush. Until the 1870s this system was only rudimentary but, from then until the 1890s, New South Wales financed a railway boom to the cost of $60,000 resulting in 4,500 kilometres of new track.

The first important achievement was the piercing of the Blue Mountains by John Whitton, NSW Engineer-in-chief, whose Zig-Zag line brought the central west into rapid communication with Sydney in 1876. The last was the movement of the main railway station from Redfern to Central in 1906. This relieved the congestion at what should have been only a stop on a suburban line and provided facilities for travellers which increased their use of the railway system.

For interstate or trans-Tasman transport and travel, Sydney was the main port, almost a thousand vessels being registered there by 1890. Circular Quay was rebuilt in the 1870s to handle the increased shipping; the Customs House was enlarged in 1885 to cope with the increase in business; and, during the 1890s, extensions to Circular Quay continued to allow passenger vessels to berth almost in the heart of the city, as Charles Conder's painting, The Departure of the S.S. Orient (1888), depicts so well.

Such a network of transport, combined with the rapid increase of an urban middle class fattening on the substantial pickings left by the cultivation of the golden fleece and the mining of gold, produced a new Australian phenomenon – the mobile businessman and holidaymaker. Railway travel, and the subsidiary growth of hotels for the business travellers, weekend jaunters and holidaymakers, opened up to inquisitive eyes areas that had been hitherto limited to those riding on horseback or in jolting coaches.

To cater for such an increasingly mobile and knowledgeable crowd, Kerry produced postcard series like his 'Special Blue Mountains Series' which, the sales lists announced, included 'dainty pictures of Orphan Rock' and 'charming pictures of Govett's Leap'. Then there was 'Hawkesbury River', described as 'a striking series of an Australian Rhine', as well as 'The Haunt of the Trout' – a series on the 'beautiful Snowfield rivers of the Monaro'. For those who travelled overseas, there were souvenirs like 'Geysers and Hot Springs, New Zealand', forty-eight hand-coloured pictures, 'illustrating the various beauty spots of New Zealand'.

The growth of skiing and winter sports, which Kerry himself helped to promote, was marked by the publication of such series as the 'Kosciusko Series', and 'Hotel Kosciusko', described breathlessly as a "Wonderfully Unique Series of Pictures'.

The period between the 1890s and 1910 was marked by great growth in rural townships. The arrival of the railway line revolutionised the economic life of the farmer and the consequent rise in wealth was reflected in a spate of building in rural areas.

The bush inn gave way to the hotel equipped with verandas, iron lace, baths and white table linen. Country towns developed a 'scrub aristocracy' of doctor, parson, headmaster and solicitor, and they in turn urged the erection of neo-Gothic churches, neo-classical banks and neo-Tudor schools. Kerry & Co. captured this pride in local achievement and sold the resultant postcards to visiting relatives and business travellers.

Over 250 New South Wales country towns were photographed by Kerry's field photographers, the list from Austinmer to Yamba filling two pages of the firm's catalogue.

|

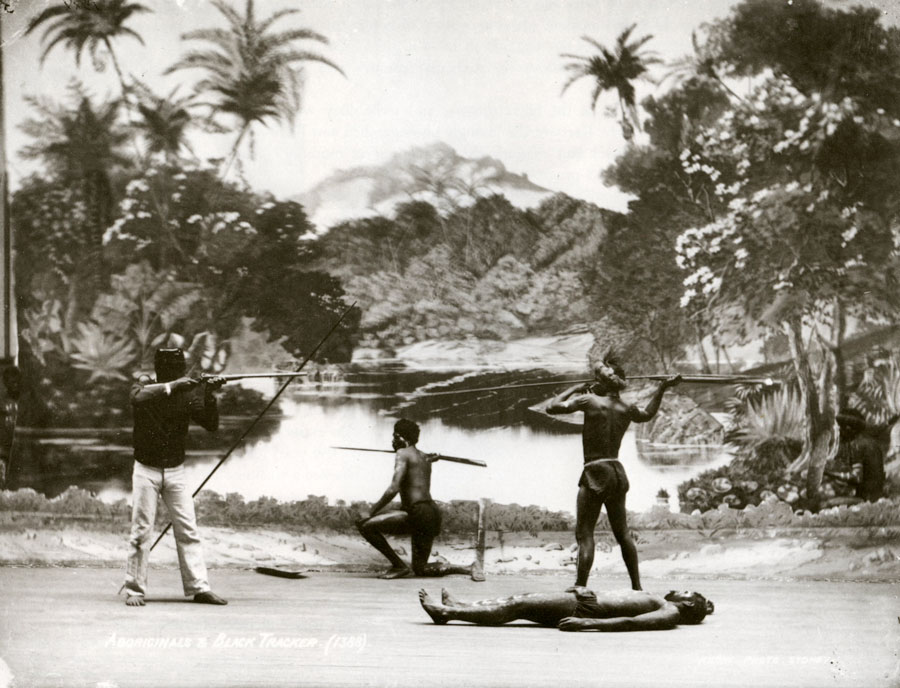

Aboriginals and Black Tracker

(postcard studio photograph)

|

Another series of photographs produced by Kerry & Co. were those on Aborigines. Three sets were printed – and reprinted several times – the justification being that they were 'splendid studies of our fast disappearing natives'. If this justification was the real one, the claim needed no more proof than the Commonwealth statistics which showed that, between 1901 and 1911, the Aboriginal population had dropped by half, to a mere 19,000.

One suspects, however, that there were other reasons for the popularity of these prints. The constant parade of bare-breasted Aboriginal girls staring sullenly at the camera suggests that Victorian prudery and racism had raised its head again – nudity was acceptable as long as it was not Anglo-Saxon. There may have been another reason. Now that the native race was broken and seemingly dying, the viewer would no longer be culturally threatened by Aborigines and could regard them as elements of exotica, upon whom the urban Australian could safely expend some mild curiosity.

A large proportion of Kerry's photographs depicts rural life. These series – 'Pioneer Life', 'With the Settler', 'Bush Sketches' and the like – portrayed rural life that most people thought of as the 'real' Australia.

It is significant that series no. 105, although entitled 'Australian Life', included no photographs of urban existence. They are all pictures of country life – 'Cutting out Cattle', 'Rabbit Industry', 'Teamster's Camp', 'Tank Sinking', 'Mail Coaching', 'Swagmen', etc,

|

Drafting Sheep

Photographed in the New England District, it shows a small number of the 45,560,969 sheep that, in 1911, were grazing on New South Wales paddocks.

This was one of many photographs lor the Government of New South Wales and it was reproduced with the more likely title of 'Penning Sheep for Shearing' in the Immigration & Tourist Bureau's 1912 publication, Pastoral NSW.

|

| |

|

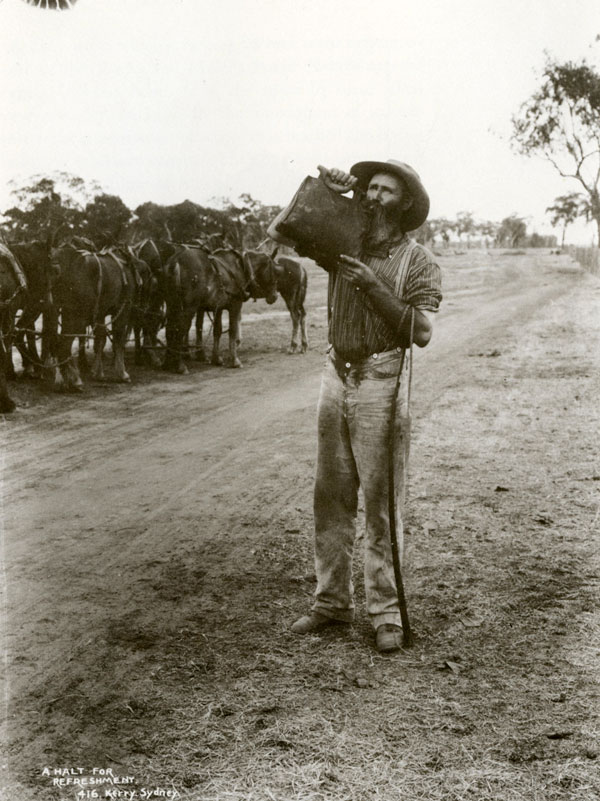

A Halt for Refreshment

This is a George Bell photograph of a drover. By the time this photograph was taken, bullock wagons were everywhere being replaced by horse teams. Because horses could travel twice as fast as bullocks, farmers preferred to use them when the roads improved. Unlike bullocks, however, horses were expensive, and spare ones were always needed. |

The Australian myth – that real moral values were to be found on the frontier, and that Australia was, like the United States of America, peopled by God's chosen race, free from the vices of the old world and called into being to redress the balance of the old – was at its zenith in Edwardian Australia. This myth, trumpeted by the Bulletin with its egalitarian and democratic sentiments, was expressed vividly in Henry Lawson's poems. The Heidelberg School of painters, notably Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin, painted an urban idealisation of the bush, with depictions of settlers down on their luck, woolshed hands embracing the golden fleece, and rural anti-heroes committing robbery under arms.

The adulation of the frontier was carried on by Kerry & Co. It is noteworthy that the scenes of rural life are rarely specific in their location. These 'stirring pictures of life and incident' are seen as icons of honest toil and egalitarian virtue. Their anonymity does not degrade them – it gives them a universal Australian quality that lifts them above the particular country area in which they were taken.

If virtue resided in the bush, progress and technology were at home in the towns. Accordingly, Kerry & Co. lovingly photographed new buildings, fresh from the builder's trowel and mason's chisel, standing as monuments to Victorian wealth, planning and progress.

There are in the Tyrrell collection some notable omissions and individualities. Whether it was Kerry's trenchant Irish background or not, the firm showed a distinct preference for Roman Catholic subjects over all other religious bodies – Cardinal Moran, St Mary's Cathedral, country catholic churches or bush presbyteries predominate.

Another oddity of the Tyrrell collection is the surprisingly small number of pictures of Victorian or Edwardian rail or sea transport. Such an omission is rare for one of Kerry's tradition where pictures of trains snorting at stations or clippers resting at wharves were commonplace. It is even rarer when one considers the importance of Sydney to the whole network of public and private transport.

There is no doubt that the postcard business turned out, aesthetically, to be a blind alley for Kerry. Although it saved his firm from extinction and, indeed, raised it to a peak of great commercial success, within a few years it had imposed upon him and his field operators a straitjacket that emphasised a weakness inherent in late nineteenth century photography.

For a view to be attractive to a wide range of buyers, there had to be a certain blandness of presentation – views had to be on their best behaviour, neat, tidy and scrubbed clean. They had also to avoid any strong emotional content. Hence the escapist quality of much postcard photography, shown in an extreme form in Series 33, 'Canine Friends', Series 35, 'Sydney by Moonlight' and Series 34, entitled 'Youthful Australia', depicting '12 pretty and artistic pictures of Australian children taken especially for postcards'.

Victorian documentary photography could, on occasions, be a probing eye, sometimes nostalgic, sometimes brutal, often fascinating. Frank Sutcliffe conscientiously recorded the vanishing life of Whitby fishermen. William Brady documented the sadness of Civil War and J. A. Riis covered the East Side for a campaign to cleanse New York of its slums. In Australia, H. B. Merlin documented the goldfields, although most of the credit was to go to his patron, B. O. Holtermann.

|

The Equitable Building

This fine building was designed by the American architect, E. E. Raht, for the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the USA. It followed current American fashion in its rusticated lower levels, round Romanesque arches and clustered columns. It was the first building in Sydney to dispense with load-bearing walls, most of the internal structure being carried by internal columns and beams.

|

It is this aspect of Kerry & Co.'s work which is lacking. Where is the documentation of the bubonic plague of the Rocks and Miller's Point? Where are the views of the incredible housing building boom from the 1880s to 1910, when the fields of Sydney disappeared within weeks under the foundations of terraces or villas?

Where is the systematic documentation of scenes that marked the laying down of one of the world's largest tramway systems? There is no documentation of the bitter strikes that rent the social fabric of Australia in the 1890s as miners, shearers and seamen fought for a fair wage and fair conditions.

Sydney was famous for its brick-kilns and sandstone quarries but Kerry & Co. never went there. Nor did they follow the process of changing these materials into such grand buildings as Queen Victoria Markets and the Lands Building.

None of these subjects would have been suitable for the postcard business. Pictures with implied social comment or criticism would have been of sectional interest only and of no interest at all to the mass of card buyers. The series on rural life was no exception. Here the prevailing emotion is one of misty-eyed sentimentalism for the lot of the 'fair dinkum Aussie in the bush'.

They are pictures of heroic toil and transcendent national pride. No one looking at the firm's rural card selection would guess that the 1890s was a period of depression, foreclosed mortgages, brutalising rural child labour and blasted hopes. Nor would they know that the farmer's lot was vulnerable to fire and high bank rates and that, at the turn of the century, Australia experienced the worst drought in its recorded meteorological history.

|

Mrs Chapman

|

If the overall selection of views is bland and sentimental in its choice of subjects, the treatment is no different. The photograph has a quality of immediacy and the stare of the photographed can dominate the image.

Victorians did not appreciate this stare, as Manet discovered in 1863 when he painted his cheeky Olympia which at the Paris Salon had to be repositioned at considerable height in a desperate attempt to avoid attention and attack. This frontal, staring face was usually avoided by Kerry, except for Aborigines and children.

Like the photographs of criminals, their stare could be outgazed from a position of racial or adult superiority. But in this respect, the firm of Kerry and Co. was no different from many of its contemporaries, which also followed the painting convention that eyes should be either averted from the gaze of the viewer or distanced from the lens so that no stare intruded upon the viewer's personal space.

But even the averting or distancing of the eyes could still produce photographs that had an immediacy, although the human figure might be reduced to a static element rather than an instrument of action or confrontation. Henry King, Kerry's less flamboyant contemporary, could add that edge to many of his photographs.

It is disappointing to note that when Kerry or his operators took the same view or scene, in every case where I have had the opportunity to compare, there is a prevailing blandness in Kerry's work that King frequently overcame.

Having commented on the character and quality of much of the photography that came from Kerry's business, it is necessary to look at the historical context of the work. Only when one has done so can one realise why topographical subjects dominated Victorian photography in such a wholesale fashion. For the fact is that, had photography been born at another time, its history would have been totally different.

To read photographic history today is to be assailed by an all-pervasive historiography. Underlying most writing is the supposition that photography is a story of progress – from the Camera Obscura to the Leica, from the collotype to fast film colour photography. Such a history of progress is therefore dominated by the triumphs of applied science.

One forgets in this triumphal procession that there were others for whom technical innovations were only part of a larger process – the development of an artistic potential and rationale. W. H. Fox Talbot, the well-to-do gentleman of Lacock Abbey, brought photography to the United Kingdom with his creation of paper-prints or collotypes.

But he also endeavoured in his photography around the abbey to create compositions that showed the imposition of order by man upon the unruly world of nature.

A Norwich painter/photographer of the 1840s, W. H. Hunt showed a fascination for spatial relationships in his photography. Julia Margaret Cameron had artistic intentions too – hence her preference for large-scale, soft-focus portraits in the 1860s. It was an artistic intention which Dr P. H. Emerson was also to attempt in the next two decades.

Such an attitude towards photography was never successful. Putting energies at the service of art through photography resulted in artistic frustration and public apathy. For what the public wanted, and was to get with increasing skill, was sharply rendered, rich toned realism.

The great proponent of this was Roger Fenton. His glass plate negatives of the Crimean War, his prints of ruined abbeys, rural England and foreign lands were greatly admired, much more than the speculative work of Talbot, Hunt and, later, Cameron and Emerson.

|

Blue Gums

These country girls are swinging from Blie Gums that have been inundated by a Riverina flood.

|

By the 1860s photography was a popular medium. Its techniques were no longer imprisoned by copyright and the dry plate process was soon to sweep all before it. High Art in photography was a lost cause and realism was triumphant. The middle class, whether they be Florentines of the Quattrocento, Dutch importers of the eighteenth century, or Birmingham industrialists of the nineteenth, have always enjoyed realism, and photography began to exploit this preference on a scale that no painter could emulate.

The public was master, and was both generous and undemanding – undemanding of originality. The increasing financial rewards for this topographical photography became so lavish that they acted as a bulwark against any inspiration beyond the commonplace. No wonder Baudelaire was to wail that photography was 'an upstart bourgeois industry, which, like all material progress, has contributed to the impoverishment of the artistic greatness of France'.

It would, however, be wrong to see the history of photography as the suppression of imagination by the juggernaut of Victorian technology – as a battle between the aesthetic few and the philistine masses. There was a rationale for this enthusiasm for topography which, in a pluralist world, has as much justification as any other art movement.

That photography did not see itself as an art form at this time, despite the muffled protests of the few, was the result of the milieu into which it was born and the implicit prevailing philosophy that shaped, and was shaped, by photography.

Not that photographers read the philosophy of philosophers but they were aware, even if darkly, of the philosophy of applied scientists.

The fine arts were increasingly influenced by an Hegelian enthusiasm for the world of the spirit – for moral uplift, for every picture to tell a story. Photography, at this time, turned its back on Hegel and followed J. S. Mill and the empiricists, whose empiricism was built on, and validated by, the observed phenomena – phenomena which must only be observed and not manipulated or interpreted.

This empiricism was the philosophical foundation of much Victorian intellectual life, explaining and inspiring an age which was the golden one of the natural sciences. Exploration, improved transport and massive emigration opened up a vast and uncatalogued world of bugs, beetles and botany.

Taxonomy flourished as European man endeavoured to classify and, in many cases, exploit them. Zoologists used empiricism to support Darwin's Origin of Species. Natural science museums and taxonomic biologists became a growth industry; geologists were employed by colonial governments to look for gold or tin; while on a lesser level, individuals began butterfly collections, country parsons reported on the migration of birds, and schoolboys risked life and limb to add yet another egg to their cotton-woolled collections.

Even the fine arts were affected. Courbet, while painting the Barbizon countryside, snorted that he would only include angels in his paintings if he could be shown one. The Pre-Raphaelites developed an almost surreal concern for the detail of every lily and wildflower. Of such was John Brett's The Stone Breaker (1857-8), whose geological exactitude so delighted Ruskin that he wrote, 'it is a marvellous picture, and may be examined inch by inch with delight.'

|

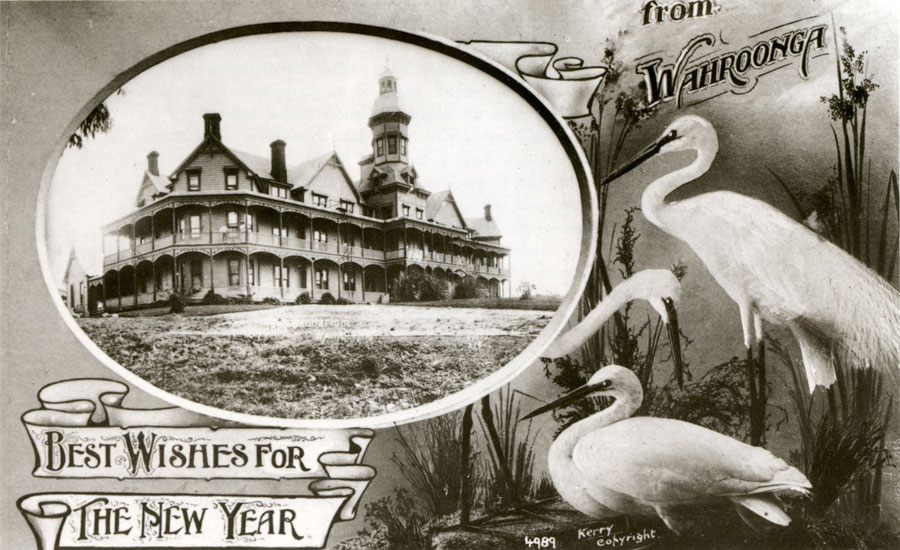

Postcard depicting the Sydney Sanatarium at Wahroonga

|

Photography reinforced and was vitalised by this all-pervasive enthusiasm for empiricism. It would record the observable phenomena, whether it be the battlefields of Gettysburg, the windmills of Montmartre, the slums of lower East Side, or the locomotive techniques of a galloping horse or a running man.

In this respect, Kerry & Co. were typical of their era. The regret is that economic constraints (or was it imaginative ones?) frequently limited the scope of the firm's cameras to a restricted and socially acceptable slice of the observable world. But to criticise Kerry for having no Hegelian soul is to regret that African bushmen do not paint frescoes or employ the rules of perspective.

To conclude. Photography was a Victorian product. It harnessed the current enthusiasm for applied science and technology. It served the current philosophy of empiricism. When it emphasised the transitory quality of life and the immediacy of the medium, it could become, without the props of Hegel, a great art form in its own right.

The work of Charles Kerry and his operators is as much an exemplar of prevailing tastes and of Victorian attitudes towards photography as a documentary record of the period.

>>cover & contents page | Rise & Fall of Kerry & Co | The Man & The Photographer | The Collection | The Plates | Biography | Kerry page

|