|

cover & contents page | Rise & Fall of Kerry & Co | The Man & The Photographer | The Collection | The Plates | Biography | Kerry page

The rise and fall of 'Kerry & Co

Charles Henry Kerry was born on his father's sheep property – Bobundra Station – on the Monaro Uplands near Bombala and Cooma in 1857*. An early interest in the new-fashioned photography was not enough to distract him from his decision to become a surveyor.

He spent some time as an adolescent working in the field and intended, on leaving school, to spend time learning draughting and the theoretical part of surveying. As the result of encounters while at secondary school in Sydney, Kerry became increasingly interested in photography and arranged to accompany a travelling photographer on his country tours.

Although the photography done was almost exclusively portrait work, the remuneration Was good.1 The nature of the work and its reasonably high financial returns appealed to Kerry. His plans for surveying were dropped.

At seventeen, Kerry left school and entered the portrait studio of A. H. Lamartiniere at 308 George Street, Sydney. It was not a happy introduction to the business world. |

|

|

| |

Charles Kerry at 60 |

Dogged by debts, Lamartiniere quit the firm, leaving behind many unhappy creditors. Forced to sell his comfortable home at 'Seven Oaks', Homebush, Lamartiniere moved and, in 1858, Sand's Directory recorded him as running a modest portrait business at 3 Albermarle Street, Newtown.

Left with only the name of the firm and substantial debts, young Kerry refused to capitulate. He worked long hours improving the portrait business and by 1883 had paid off all the creditors, and was recorded as working under the name of 'Lamartiniere & Kerry'. In the following year, Kerry decided to go it alone and Sand's Directory described the firm as 'Chas. H. Kerry, Photographer and Artist, 308 George Street'.2

Writing seventy years later, Harold Cazneaux, the grand old man of Sydney photography, recalled those portrait studios of Kerry's business days as being 'filled with old imitation furniture and painted backgrounds, ponderous cameras and iron head rests'. As to the photographers, he was accurate, if harsh. There were 'few operators who possessed artistic imagination – they were in a rut and just followed the technique and practice that was being done by others. Very few have lived on as pioneers or as ones who have contributed to the advance of artistic photography. They closed their doors, their pockets full of money, and just slipped into the past.'3

Kerry was a man of initiative and hard work, aided by a good business sense. He subscribed to photographic journals regularly and eagerly studied the reports of overseas innovations. Thus, in 1888, Kerry began using magnesium flashlight, inspired both by Dr Vogel's paper read to the Berlin Society in 1887 and the experiences of another Sydney photographer, Henry King.4

Ten years later, in 1898, Kerry read an account of a London photographer who had used electronic light to take photographs of a ball. Kerry was impressed. At a fancy-dress ball at Leigh House, he erected a temporary studio on the roof with two large arc lamps fed by a galvanic battery of 400 cells. '

It was the most brilliant object of illumination and deservedly obtained universal admiration.' In all, seventy-six photographs of over a hundred people were taken — 'an unprecedented performance'.5

|

The Palace Theatre

This is a stereoscopic and flashlight photograph of the play, A Bunch of Keys, at the Palace Theatre, George Street. Opened in 1896, the 'Palace' was described as being decorated in 'elaborate Indian ornamentation', an effect made possible by the embossed sheet metal manufacturers, Wunderlich Patent Ceiling and Roof Company Ltd.

|

Flashlight continued to intrigue Kerry. Reviewing his photographs of the Palace Theatre in 1898, The Australasian Photographic Review commended the work of Kerry's studio, noting that he had made 'a specialty of this class of work'.6

Following his reading of overseas journals, Kerry then designed a multiple flash machine which his good friend, H. J. Quodling, Inspecting Engineer for New South Wales Railways, constructed. It consisted of a frame holding six blow-through magnesium lamps. These could be used in any combination. The release of the air pressure from a pumped-up air reservoir produced a spectacular flash, which Kerry used frequently for large interior views.7

From the mid-1880s, Kerry's business boomed. In 1885 Lord Carrington arrived as Governor of New South Wales, and Kerry was soon assisting Lady Carrington, an amateur enthusiast, with her photographic endeavours. In 1890 Vice-Regal patronage was made official. The royal coat of arms and the superscription, 'By appointment to His Excellency Lord Carrington', now graced Kerry's shopfront.

Kerry's enthusiasm for the outside life was not dimmed by the need to spend hours with his staff dealing with wedding groups, baby photographs or official portraits. He still clung to his hobby of outdoor photography, even though it meant using the wet plate process. This was a cumbersome method. The collodion-coated glass plates needed to be developed immediately in the portable darkroom that accompanied every foray out of the studio.

Then came the break which Kerry was to exploit with such commercial success. The marketing of the dry plate in Europe in 1878 took away all the hassles associated with the wet plate process. Using gelatin instead of collodion to hold the light-sensitive silver on to the plate, it was no longer necessary to travel with a horse-drawn darkroom and a range of chemicals. All the landscape photographer now needed was a camera, tripod and a box of plates.

Although dry plate techniques were slow in winning acceptance, Charles Kerry was quick to take advantage. By the 1880s his dry plate business was firmly established. To handle the increasing business, Kerry went into partnership with C. D. Jones, an ardent amateur in photography.8

'Kerry & Jones' now became well known for their scenic views, and for selling multiple prints of recent events or rural scenes – the forerunners of the postcard business of Edwardian Australia.

The ease in using the dry plates meant that within hours of taking a photograph, the display window at 308 George Street would have copies for sale. Before the advent of the illustrated newspaper, such rapidity paid dividends, and the window became the pictorial news-sheet of Sydney. Pictures of Vice-Regal levees, processions, foundation stone layings, race meetings, cricket matches and religious processions were produced, and sold, in their hundreds.9

In 1892 Kerry exhibited several bromide enlargements of life and scenery of New South Wales which had been selected for exhibiting at the Chicago International Exhibition (World's Columbian) of 1893.

Included in these were thirteen 'curious pictures of caves taken by flashlight. One of these caves [was] discovered by Mr Kerry himself last year...' There were panoramic views of the match between Lord Sheffield's XI and Australia in 1891, whilst special praise was reserved for his enlargements of ‘Lanyon Woolshed, near Queanbeyan', and 'Fishing Rock, Clifton'.10

|

A Homestead on Cox River

|

Enlarging was then in its infancy and the manipulation of the apparatus required a great deal of skill. Enlarging was mostly by sunlight, subject therefore to the vagaries of the weather, whilst bromide paper was an uncertain quality, with no two batches being the same.

Throughout the 1890s, Kerry continued to build up his stocks of scenic views. In 1895, a peak year for travelling, he was commissioned by the New South Wales Government to travel through New South Wales and secure a set of portraits of Aborigines and corroboree scenes. Kerry also commenced his 'Squatters' service', travelling by train and horseback to homesteads all over the state.

The negatives would be developed on the spot and from the resultant contacts, orders would be taken which would be filled from Sydney on his return.11

In such a way, a marvellous collection of Australian bush life was commenced which Kerry added to over the subsequent years.

Photographic journals are peppered with allusions to Kerry's growing involvement in the view trade. Thus, for instance, in 1902 it was reported that 'a good Christmas trade is being done in local views',12 whilst in 1893, another journal had already noted that 'Kerry & Co. are just now tempting the public with a fetching series of the best of New South Wales Art Gallery pictures. They are most effectively coloured.'13

In 1885 Kerry met his gravest photographic and business challenge. Walter Barnett, the dignified and urbane Melbourne photographic entrepreneur, opened his Falk Studios in Sydney.

Surrounded by a team of highly proficient craftsmen, Barnett produced portraits whose quality was unchallenged and whose presentation was lavish. A master of the control of light, he used the newly invented dry plate process to produce portraits which caught the bone structure and skin tone of the sitters. Supported by a luxuriously appointed studio and clever advertising, Barnett turned Falk Studios into a veritable goldmine.

If Kerry was to seek out the company of sportsmen, graziers and businessmen, Barnett's became the studio for actors, society women, artists, writers and architects. It was a galaxy that included Rolf Boldrewood, 'Banjo' Paterson, Sir John Longstaff, Sarah Bernhardt and all the actors who worked for J. C. Williamson.

In the face of such opposition, Sydney photographers were stunned. Technically they were inferior and socially they were not as attractive. Their only weapon was price-cutting. Throughout the late 1880s and early 1890s the war raged, with several firms folding up because of the competition – competition made even more vicious by the depression of the 1890s.

Kerry shrewdly surveyed the future. He attempted to cut prices. He succeeded only in breaking up the partnership. Jones refused to accept lower prices and withdrew from the business.

Re-established as 'Kerry & Co.' in 1901, he decided on a new tack. He would leave Falk's portrait work virtually unchallenged, but place an increasing amount of time and energy into the view trade. As a lover of the outdoor life, it was not a hard decision to make. The increasing interest in tourism as the railway network rapidly covered the state, and the rise in national pride as the country was swept on the tide that led to Federation, proved it to be the correct one.

Kerry's decision to rationalise his business on the basis of local views at this time was fortuitous – the picture postcard craze was about to begin. Prior to this, Kerry had produced multiple prints of views. But by 1901 the new fad was well underway.

The fashion had begun modestly in the United Kingdom about 1894. Since 1899, when Raphael Tuck & Sons commenced in business as picture card printers, the fashion had become firmly established. Thus, in 1903, Kerry had over 50,000 postcards of '37 colonial views reproduced in single, or 3 colour process'14

Kerry's monopoly of the postcard business in New South Wales was established early, and he was soon having his bestsellers reproduced by collotype in Germany. It was a financial bonanza that was to rocket him into a position of considerable economic security.

In this enthusiasm for scenic views and the postcard trade, Kerry & Co. did not neglect the local event. For this, assistants would toil for long hours to have the dozens of photographs ready for display and sale within a short time after the event.

In 1895 the untimely death of the Governor, Robert Duff, was scooped by the firm.'5 In 1897 a flashlight photograph of the Federal Conventioneers was taken and reproduced in the Sydney Mail.15 The picture was happily lit, the detail excellent, and the likenesses all good', enthused the Australasian Photographic Review.16 In 1901 Anthony Hordern's disastrous fire provided Kerry's with a golden opportunity,17 whilst the picture of Lord Hopetoun taking the oath as first Governor-General of Australia was a scoop in the future tradition of photojournalism.18

There were two spectacular events in 1908 that provided Kerry's with great opportunities. The first was the visit of the American Fleet, known as the Great White Fleet. The second was the Burns-Johnson fight.

Gleaming in its fresh white paint, the American Battle Squadron, led by Admiral Sperry, was a most impressive sight as it steamed into Sydney Harbour in April 1908 for a ten-day junket. Sydney gazed in awe at the largest show of naval strength it had ever seen. In anticipation it had festooned its city streets with triumphal arches and bunting.

Kerry was anxious to capture the procession of battleships and cruisers. He toyed first with the idea of a camera suspended from a kite, but settled for a movie film and panoramic views. The film footage was ruined by hasty drying of the thirty-metre lengths of cine film, but the forty-centimetre 'Cirkut' panoramic camera, specially imported for the purpose, overcame difficult teething problems and a large number of 115 cm x 50 cm prints were obtained, many being sold to enterprising commercial firms as showcase advertisements.19

The Burns-Johnson fight took place at Rushcutters Bay stadium in 1909. It was a world championship fight in which Jack Johnson, the big American negro, almost slaughtered the American heavyweight Tommy Burns until, in the fourteenth round, police had to intervene to stop the fight.

Kerry & Co. secured all rights to supply photographs. The Daily Telegraph arranged with Kerry to supply photographs that could be made into half-tone blocks ready for publishing in the evening edition of the paper the same day. Kerry had special cabs in readiness and, the moment the fight was over, the operators jumped into them. Twenty-six minutes later five 40 cm x 50 cm enlargements were delivered to the paper and within two hours 10,000 newspapers were printed and ready for distribution.20

Ten half-plate negatives were selected as being the most interesting and for eight hours two operators, assisted by a lad, produced 590 enlargements, each man working from three developing dishes. At 6.00 a.m. they emerged, their work done, to be taken by Kerry to breakfast at a Hunter Street cafe, and having the satisfaction of filled display cases and plenty of stock for the 27 December crowds who subsequently poured into the shop. In all, Kerry had a contract to supply 2,000 enlargements of the fight in sizes 25 cm x 20 cm or larger.21

|

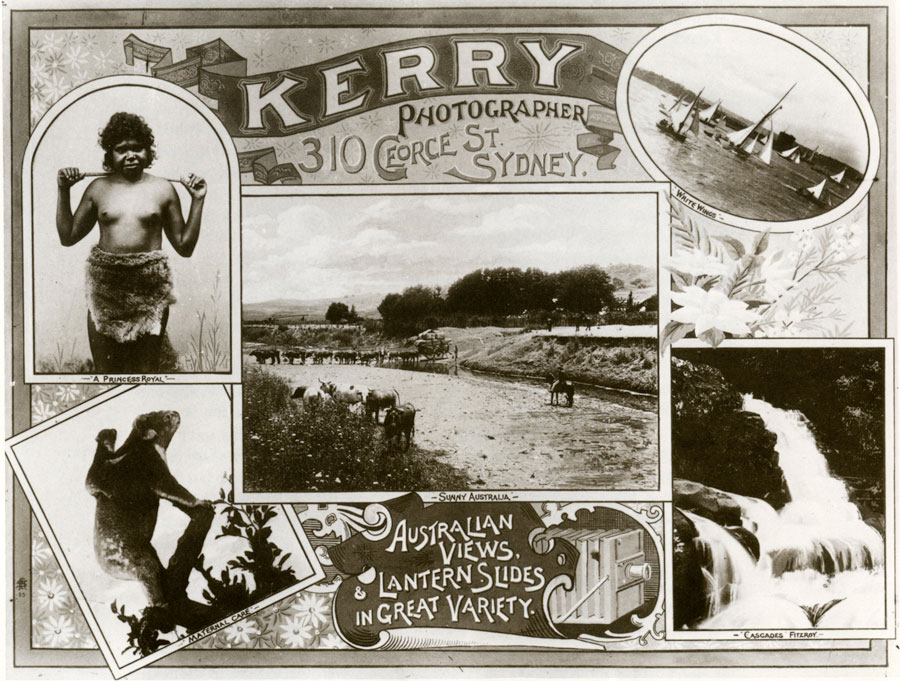

Kerry & Co's Studio Advertisement, 1895

|

Kerry's reputation as a photographer who was easy to get on with and who always produced the goods as promised, resulted in several Government commissions.

In 1895 he made photographic records of the Royal National Park, south of Sydney, for the New South Wales Government. Later he made a complete coverage of Queensland's widely scattered artesian bore system for the Government of that state. Working in the Queensland summer posed its problems, as the heat rapidly increased the sensitivity of the dry plates.

With no refrigeration or air-conditioning, Kerry was forced to travel with the plates encased in blankets and even then found that a quarter of the normal exposure was sufficient.22

The most difficult commission he ever received from the New South Wales Government was photographing the Jenolan Caves. By the light of candles, Kerry and his team clambered through the caves, an arduous job. To take the photographs, Kerry had constructed blow-through flash lamps. But on firing, these emitted a dense cloud of magnesium oxide dust which, in the still of the caves, took a day to settle and forced the team to move on to a new cave for each exposure. 'The man who would systematically explore the caves and make records should be of muscular build and have great strength and endurance. One is forced to place himself in the most awkward positions and places... In my climbing about, I have had many falls, and have, in cave working, smashed up three cameras beyond repair.'23

By 1891 Kerry had begun to weather the economic storm caused by the price-cutting which resulted from the establishment of the Falk Studio.24 Staff began to increase dramatically in number from the small team that had originally worked for him.

The complexity of his business is illustrated by the agreement reached in 1904 between Charles Kerry and the Employees Association, a union established under the new Arbitration Act of 1901. A career structure was thereby laid out for staff, along with overtime rates, holiday and piecework rates.25

It is an interesting comment on the way photographic studios treated their staff that this decision by Kerry raised a storm of protest amongst several of his fellow businessmen, who felt he had not taken them into his confidence. Within weeks of these fair conditions being agreed upon, a meeting was held to establish an association of photographic employers to oppose the industrial agreement entered into by Kerry & Co.

If such an agreement became a common rule, commented one irate member of the meeting, it would force large employers into establishing workrooms in adjacent states. Kerry was known as a strict employer, but the sweatshop conditions that prevailed in some other institutions were not to his liking.26

In 1896 an attempt was made to establish the Photographic Union of New South Wales – a body for professionals, stock dealers and process workers. Established on 29 June at Aaron's Exchange Hotel, with Kerry as its secretary, it aimed to hire clubrooms, exchange technical advice and organise exhibitions. Rooms were eventually found at 10/12 Hunter Street, but the pressure of private commitments – Kerry married in January 1897 were such that he resigned in five months. Within a short period the Union had collapsed, leaving all to its rival, the Photographic Society of New South Wales.27

At the age of forty, Kerry was firmly established. The cost cutting war was won and the depression of the 1890s beaten. On 23 February 1898 the Minister of Works, the Hon. J. H. Young, officially opened the firm's new premises at 310 George Street.

The architect, H. C. Kent, had designed a four-storey building whose lavishness and size had no rivals in Australia. The vestibule and stairways were elaborately furnished in polished cedar and rosewood fittings. On the first floor a large gallery showing 75 cm x 100 cm enlargements of New South Wales views was sited, complete with display tables and albums.

The studios on the third floor could take up to seventy people. They were furnished with opaque curtains to achieve the same light effects as Walter Barnett had capitalised upon so successfully in his Falk Studios. Water pipes in the roof were filled with flowing cold water in an attempt to keep the temperature down to a more comfortable level. On the top floor were the enlarging, printing, retouching and mounting workrooms, while the roof was equipped for outdoor printing.28 It was a monument to Kerry's initiative, hard work and phenomenally successful postcard business.

Within six months Kerry entered into a business arrangement with Saunders of Melbourne and established process work as a branch of his business. Capitalising on the new photo-mechanical process, 'it aimed to "do or die" in the supply of the best class of work only, holding to the faith that such is not possible at the low rates now ruling in some quarters, and disclaiming the intention of "cutting" merely for the sake of getting orders.29

By now, Kerry was a businessman administering a large establishment and was completely reliant upon his paid photographers, namely George Bell, Harold Bradley and Willem van der Velden. Administration, not photography, had become his forte.

George Bell was the earliest of Kerry's field photographers, having commenced work in 1890 and not leaving until 1900. Born in Cornwall, he spent some early days at sea before eventually becoming surveyor to the Victorian Government Engineers. He went on the 1890 'Victory' Expedition to' New Guinea in the company of Burns Philp & Co. and in the pay of the New South Wales Government, using his skills as a photographer to document the expedition.

A brief sojourn with the pearling industry in northern Queensland, during which he did press work, was followed by work with Charles Kerry. In 1890 he was sent into the interior of New South Wales with a fully equipped photographic kit and a carefully mapped-out route. It was the beginning of many such journeys. In 1900 he left Kerry's to join the Sydney Mail as a press cameraman.30

Harold Bradley worked for Kerry's from 1893 to 1911. Born in 1875 in Birmingham, Bradley was stricken with rheumatic fever at the age of thirteen. During his long convalescence, a professional photographer indulged him with the present of a camera. Migrating to Australia in the belief that the climate would improve their son's health, Bradley's family settled in Petersham.

Now enthusiastic about photography, Harold Bradley obtained a position as a retoucher with Walter Barnett at Falk Studios in 1891. With returning health came increasing ambitions and, after a few months at Claremont's in the Royal Arcade, Bradley joined Kerry & Co. in the same year. Under the senior operator, U. C. Cruden, he continued his retouching and then, when the enlarging hand left for the West Australian goldfields, Bradley began doing the firm's enlarging. From there he progressed to studio operating and, by 1899, began taking outdoor photography.

Bradley's most memorable achievements were the Anthony Hordern fire, the panoramas of the American Fleet, the exclusive photographs of Sir Robert Duff’s funeral, the embarkation of the troops for the Boer War, and the inauguration of the Commonwealth, with Lord Hopetoun taking the oath.

This last he achieved by breaking the bounds allotted the photographers and running forward towards the rotunda where he set up his camera with a long focus lens, thereby scooping the scene.31 Using a whole-plate camera, Bradley covered the Burns-Johnson fight.

He also made many trips to country areas and, like Kerry and Bell before him, took photographs for property owners and the postcard trade of homesteads, stock and residents. In 1911, when Kerry decided to retire, Bradley left to become the field photographer at the recently opened Melba Studios at 65 Market Street, Sydney.32

The last field operator to join the firm was Willem van der Velden. Born in 1877 at The Hague, the son of the painter, Petrus van der Velden, Willem sailed with his family in 1889 to New Zealand, and settled at Sumner in Christchurch. Influenced by a local camera enthusiast, Walter Burke, both father and son developed an interest in photography. In search of better prospects, the family sailed to Sydney on the S.S. Monowai in 1898.

Young Willem assisted his father in setting up a photographic studio – it was soon to fold up – and then began looking for freelance work. Although a shy and somewhat inhibited person, 'Van', as he became known, plucked up courage to call on Charles Kerry.

Impressed by his work, Kerry gave him the job of documenting the streets of Sydney for an assignment the firm had recently undertaken for the Australian Town and Country Journal. Their intention was to place modern day photographs in the new half-tone process alongside early woodcuts of colonial Sydney.33

The commission took nine months. Using a wide-angle lens and perched on top of a mobile tower, Van took dozens of photographs, shifting location many times according to the position of the sun. This vehicle was designed for Kerry by H. J. Quodling, an amateur photographer and New South Wales Railway Inspecting Engineer.34

It had a useful device whereby the camera level remained constant, thanks to a pendulum which levelled the camera, irrespective of the slope on which the lorry was standing.

|

Beel's Bore, South-West Queensland

|

| |

|

| Pitt Street, Sydney |

Subsequent freelance work took Van to the Swiss Studio and the Crown Studios before he joined the Kerry organisation as a permanent operator in 1907, specialising in Sydney views and thereby continuing to build up the firm's postcard selection. The most spectacular of Van's coverages was the arrival of the American Fleet, for which he used Kerry's recently imported forty-centimetre 'Cirkut' panoramic camera, the introduction of which caused great interest in Sydney photographic circles.

Assisted by young Robin Cale, Van used the 'Cirkut' to record panoramas of Sydney from every lofty vantage point. The most nerve-wracking of these, from which a harbour panorama was taken, was the top of the high chimney which stands alongside the Mining Museum in the Rocks.

When Kerry started to loosen his hold on his own photographic organisation, several trained staff began to go their own ways in anticipation of troubled times ahead. Van was one of them. He joined the Kodak company to head its Sydney, technical service. In so doing, history came full circle, for he met up again with his father's old New Zealand friend, Walter Burke, now Kodak's advertising manager.35

From the mid-nineties Kerry had developed a great amateur interest in geology and frequently returned from the country with mineral specimens in his camera bag. This hobby was eventually to lead him to a full-time interest in mining. In 1913, aged fifty-five, Charles Kerry decided to change his business interests.

From being a photographic entrepreneur, he now became involved exclusively with mining concerns. For a while he had mined a silver-lead deposit at Yerranderie (NSW) and had speculated in Broken Hill stock. He now founded the Malayan Tin Corporation, and was later Chairman of Directors of the Ratrut Tin Dredging Company and of the Takuapa Company.

He handed his photographic company over to his nephew. But, without the Kerry drive and initiative, it began to founder. The decision of Harold Bradley to move to the Melba Studios was a bad blow, as many of Kerry's old customers who had been handled by Bradley transferred their business to his new firm. In 1917 the firm closed its doors for the last time. A small number of the vast Kerry negative collection was purchased by Tyrrell's Bookshop, while a few albums have subsequently made their way into the State Libraries of New South Wales and Victoria, as well as the National Library, Canberra.

Kerry, now a mining entrepreneur, died, aged seventy, in 1928. His only contribution to photography in those last fifteen years were snapshots of his family and of his tours throughout Southeast Asia.36

* Various sources (Cato 1977 [1955], Millar 1981 and Stephenson 1997) rely on Quentin Burke's article of 1952, which wrongly gives 1858 as Charles Kerry's year of birth. The New South Wales Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages cites 1857, which was also used by Keast Burke for the entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography (1983: 577–578).

REFERENCES

- The Australian Photographic Journal, March 1898, p. 62

- Sand's Directory, 1884

- Harold Cazneaux to Jack Cato, Sept 1951. Letter I, Cazneaux family MSS

- The Australasian Photographic Review, May 1898, p. 29; June pp. 28-29; and July, p. 26

- The Australasian Photo-Review, March 1952, p. 155

- January 1898, p. 27, and frontis (illus)

- The Australasian Photo-Review, March 1952, p. 158

- C. Tanne, The Mechanical Eye, Macleay Museum, Sydney, 1977, pp. 57, 68; The Australian Photographic Journal, March 1898, p. 62; Sand's Directory, 1886

- Colonial and Indian Exhibition. Neic South Wales. Its Progress and Resources, 1886, pp. 40-46

- The Australian Photographic Journal, Dec 1892, p. 19; Oct 1893, p. 83. The cave he discovered was the Jersey, at Yarrangobilly.

- The Australasian Photo-Review, March 1952, p. 143

- The Australian Photographic Journal, Dec 1902, p. 285

- The Photographic Review of Reviews, Dec 1893, p. 10

- The Australian Photographic Journal, May 1903, p. 112

- The Australasian Photographic Review, March 1895, p. 12 (illus)

- The Australasian Photographic Review, Sept 1897, p. 23; and Sept 1952 p. 560 (illus)

- The Australian Photographic Journal, July 1901, p. 150 (illus)

- The Australasian Photo-Review, Sept 1952, p. 561 (illus)

- The Australasian Photo-Review, March 1952, p. 156; August 1954, p. 470

- I. and C. Pearl, Our Yesterdays, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1967, p. 143 (illus)

- The Australian Photographic Journal, Jan 1909, p. 29; The Australasian Photo-Reivew, Jan 1909, p. 43

- The Australian Photographic Journal, Aug 1896, p. 175; The Australasian Photographic Review, Jan 1895, p. 8, p. 13 (illus)

- The Australasian Photo-Revieiv, March 1952, pp. 157-8; The Australian Photographic Journal, Oct 1903, pp. 224-6 (illus)

- The Australian Photographic Journal, July 1891, pp. 145-149

- The Australian Photographic Journal, Oct 1904, pp. 234-6

- The Australian Photographic Journal, Dec 1904, pp. 266-267

- The Australian Photographic Review, June 1896, p. 143, pp. 145-6

- The Australian Photographic Journal, March 1898, pp. 61-62; The Australasian Photographic Review, March 1898, pp. 27-8

- The Australasian Photographic Review, Aug 1898, p. 27

- The Australian Photographic Journal, Dec 1908, pp. 358-369

- The Australasian Photo-Review, Sept 1952, p. 561 (illus)

- The Australasian Photo-Review, Sept 1952, pp. 558-562

- The Australian Town and Country Journal, June-October, 1900 (passim)

- Sec above, p. 10

- The Australasian Photo-Review, Aug 1954, pp. 464-472

- Sydney Morning Herald, obituary, 28 May 1928

>>cover & contents page | Rise & Fall of Kerry & Co | The Man & The Photographer | The Collection | The Plates | Biography | Kerry page

|