Chapter Two: Contemporary Photography Magazine

Contemporary Photography magazine (CP) began in 1946 and ceased publication in 1950 (as no replacement could be found for the busy Le Guay),67 and photographers in Australia have since expressed their frustration at the distinct lack of places to have "realistic" photo-art published and displayed during mid-century.68 CP played an important role in developing photography, but no other regular publishing outlet replaced it. It can be viewed as quite innovative when compared to one of its competitors, the Australasian Photo-Review, and one of its successors, Australian Popular Photography.

The Australasian Photo.-Review (A.P.-R. 1894-1956 )was a photographic journal that catered to the amateur's need for technical articles about photographic processes and the commercial photographer's need for product information and advice. It was published by KODAK (Australasia) Pty Ltd from 1908, and contained information on photographic societies and International Salons, results of competitions, advertisements, articles on technique, and some articles on photographic styles from overseas magazines. The AP.-R. has been denigrated as being a snapshooter's manual from 1939, with little art discussion or reviews,69 although it was also known as a proponent of the Pictorialist approach to creative photography, but started broadening its outlook in the 1950s.

In 1947 W.H. Moffitt outlined why he believed Pictorialism was the only means photography had of being accepted as art, as he considered 'photographic quality' to be a limitation to artistic expression.70 The article was acclaimed by Cazneaux as a defence of the craft of handwork, but has been described by Gael Newton as a farewell to a movement which had become stagnated.71

Moffitt's article was accompanied by a section of his pictorial bromoils, and he argued that photography need not be 'chained to the negative'.72 He stated categorically that photography was not an art form: 'a picture that is machine made cannot, of course, be a work of art, for the automatic and the mechanical are antithetical to art'.73 "Modern" photography and abstraction were derisively labelled a process of 'shunting' where unusual angles and harsh lighting effects were used in nothing but a poor attempt to escape the monotonous effects of the ordinary photographic process.

He eased-off slightly in his attack towards the end of the article by admitting that spectacular results were produced in these images but denied that they belonged to the realm of art. He stated outright that pictorial photographers needed to avoid photographic quality, to 'transcend mere literalism' and to reject the bromide. He offered oil pigment processes as the solution to the aim of enhancing and idealising the picture formed by the negative: 'for my part I would shun photographic quality! Rather than submit to it I would give up trying to produce pictures by photographic means'.74

To criticisms that Pictorialist methods were hybrid processes, combining painting and photography, Moffitt explained that in his opinion 'it is a natural adaptation of the / photographic process that breaks the fetters of the mechanical and gives the worker wings, albeit more like a sparrow's than an eagle's'.75 The AP.-R. did publish articles on photographic style and artistic debate in limited quantities, but the overwhelming majority were reprinted from overseas journals, and only occasionally was there a call for non-Pictorialist photography.

Edward C. Partridge wanted to see the rejection of traditionalism in order to develop a fresh look in British photography. He believed the criteria for good photographs needed to be revised, with narrative being rejected in favour of a purely visual response to the image: texture, form, lighting, and harmony of objects should be valued over any reasoned consideration of the relationship between the units of the image.76

However, this surrealistic call was denigrated by Peter D. Snow's response. He called Partridge's bizarre subject matter 'ersatz pictorialism', and pleaded instead for good, straight-forward photography—whether pictorial, commercial, or portraiture, and warned against the attitude of difference-for-difference-sake.77

In 1954, A.P.-R. reprinted an article from the British Journal of Photography which rejected both the 'painter's vision' of Pictorialism and the glorification of photojournalism. The writer did not consider the camera a mechanical recording device, nor the only true photographic output to be documentation. He called for the removal of the 'tiredness and sameness' so evident in photographic exhibitions, and believed the diverse range of photographic papers, filters, and lenses which give a variation of depth of field and distortion, were aids which would revitalise photography, rather than the photographer resorting to the painter's pot.78

Gael Newton has written that the A.P.-R. was still quite popular in the immediate post-WWII period and had begun to include articles on modern photographic trends, but there was definitely a need for a journal like Contemporary Photography, which was more representative of contemporary photographic thinking.79

Laurence Le Guay's photographic career began when he started exhibiting in the salons in 1936, but he soon came to be noted for his energetic, outdoor fashion photography.80 He spent five years in the Middle East and Europe as part of the RAAF's photographic unit in WWII. He set up a short-lived enterprise of The Society of Realist Art with Hal Missingham and others, and then set up another studio for commercial and creative photography, after he photographed the first post-war Antarctic expedition on the Wyatt Earp for the DOI in 1948.

Le Guay did freelance work in Australia and overseas 'trying to promote photography more as an art form and as a means of communication' than it had previously been known for.81 He wanted to enliven commercial and fashion photography as well as promote a Naturalistic approach to expressive photography.

Many amateurs were disheartened at the lack of outlets for non-Pictorialist photography after WWII, and realised they were not going to be recognised as artists through their efforts.82 The only regular publication outlets for Australian photography were specialist photography journals (which favoured Pictorialism), or as book and magazine illustrations,83 and Le Guay set out to rectify this state of affairs.

Before the television, picture magazines were everyday companions which provided an important source of information and entertainment. Because photographs were considered to be truthful, objective documents, in a way written reports were not, they dominated space in these publications, and close-ups made readers feel as if they were actually on the scene—an eye witness. The main outlets for the publication of non-Pictorialist photography in the 1930s and 1940s were as photo-essays in magazines.

They reached a mass-audience but, like the directors of photographic programs in the FSA and DOI, magazine editors had control over the message that was being conveyed in the photo-essay and photographers were consequently limited in their expression of personal views and artistic craft. Sekula points out that Lewis Hine's use of the photograph as evidence in his social work photo-essays and pamphlets was similarly adopted by editors of magazines who used the photograph to prove the "accuracy" of the story.84

Picture magazines used sequences of photographs, with some written text, to provide viewers with a more "accurate" account of an event. The greater narrative form that is produced in a sequence, with or without written text, the less room left for individual interpretation of the scenes depicted. The photographer or editor can produce meaning through the order and selection of images and guide the viewer towards the "right" understanding of the work's meaning.

Pix (1938-72) was an Australian picture magazine like Britain's Picture Post (1938-57) and America's Life (1936-72) and Look (1937-71) . In the 1950s they were widely criticised by photographers as trivial and celebrity-chasing because they had adopted the post-war feeling of optimism and hedonism that pervaded society after years of the Depression and war— leading some photographers to believe they were preoccupied with scandals, trivia, and celebrities, instead of informing the public about social issues.

Photographers for these magazines were rarely given credit for their efforts and many longed for outlets where their photographs would be valued as artworks, or where they could pursue more meaningful social stories. In the late 1960s, popular picture magazines began their decline, as still-photography was surpassed by television as a prosaic entertainer and news provider, however, by then photography was beginning to be valued by the art community in its own right.

Through Contemporary Photography magazine, Laurence Le Guay encouraged photographers to bring vitality and personal expression to their photographs. He attempted to revitalise Australian photographers' interest in subject matter and its rendering in a realistic manner through his own articles and editorials, and the publication of pieces written by other photographers. The range of Le Guay's photographic interests can be seen in his photographs published during his career.

|

|

|

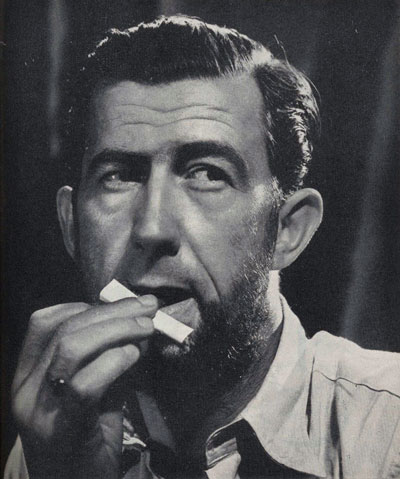

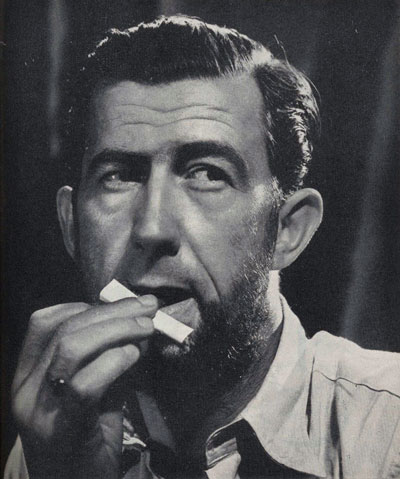

| Fig 9: Laurance Le Guay, Chips Rafferty, c1947, (Reproduced from Contemporary Photography March-April 1947, p7) |

|

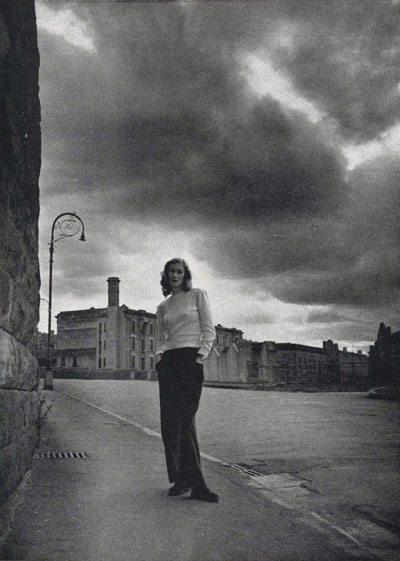

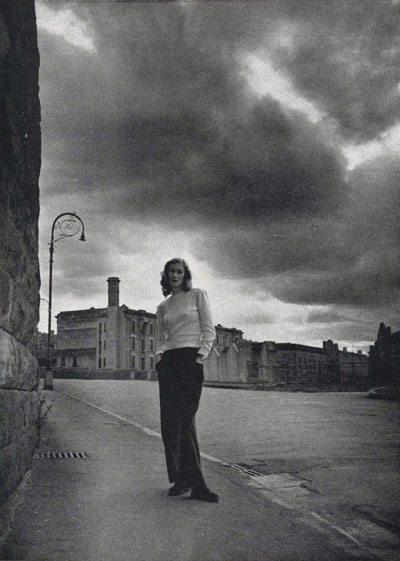

Fig 10: Laurance Le Guay, Ann Price-Jones, c1948, (Reproduced from Contemporary Photography March-April 1948, p39) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

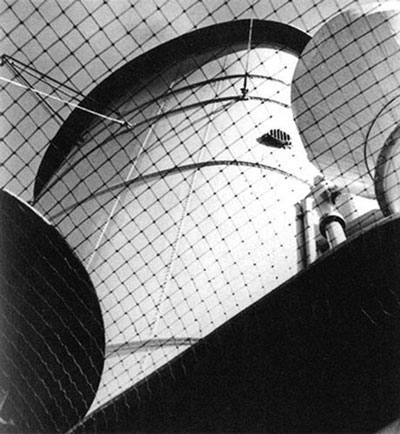

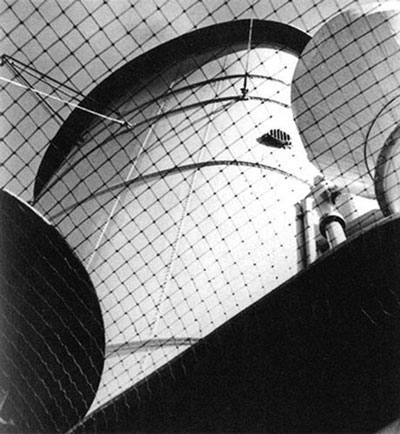

| Fig 11: Laurence Le Guay, Untitled, c1946, (Reproduced from Australasian Photo-Review July 1948, p379) |

|

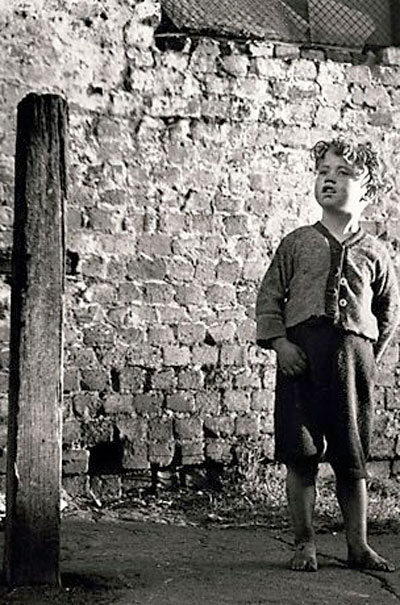

Fig 12: Laurence Le Guay, European Mother and Child C1940s, (Reproduced from Australian Photography 1947, p71) |

His candid-style portrait of film star Chips Rafferty [Figure 9], rolling a cigarette, appeared in CP (November-December 1947) and won a Silver Plaque in Australian Photography 1947; his fashion illustrations were often set outdoors in natural surroundings, like Ann Price-Jones on an uninhabited street [Figure 10], and the image of an elegant lady perusing her book near a tree in a grand back yard;85 his photo-documentary work on the Wyatt Earp's voyage to Antarctica (depicted in an image in A.P.-R. July 1948 [Figure 11]); and his humanist photographs like European Mother and Child [Figure 12] from Australian Photography 1947 which shows a woman standing tall against a background of ruins, carrying her child, and staring directly at the viewer.

Contemporary Photography provided a rare outlet for these types of photographs as well as most other styles, including absn-act, and only the best of Pictorialism. As editor, Laurence Le Guay did not run the magazine as a political magazine for social reform, despite the publication of photographs with social subjects and articles using the term 'documentary'.

Willis points out that the calls for a more realistic depiction of society through photography in the 'documentary' manner were along the same lines as Le Guay's own wish to challenge Pictorialism's reign over the photographic salon. Le Guay wished to point out that not all "location" photography was Documentary—that photography outside the studio was often labelled news, documentary or candid, in an attempt to set it apart from the arty Pictorialism.

He encouraged photographers to challenge the 'petty values' of much contemporary art and photo-Pictorialism by documenting life in an understanding and honest manner.86 Le Guay supported the use of photography in commercial, fashion, artistic, and social areas, believing that the style of expression used in photography at the time needed to be revitalised, no matter what its purpose.87 Le Guay's preferred style, whether in commercial, artistic, or personal work, was Naturalism.

As well as encouraging a new style of photographic art for amateurs, Contemporary Photography discussed opportunities for them to earn money from their expensive hobby by selling their works to be held in stock photograph agencies for publication. It was also pointed out that amateurs have more freedom to produce Naturalistic photographs, to capture the true-life of this country, than commercial photographers who need to work strictly to client guidelines.88

As well as encouraging a vital style of non-commercial photography, Contemporary Photography also set about revitalising advertising and fashion photography. Readers were offered the opportunity of having their work displayed in an international exhibition which would open at the David lones gallery in December 1947.

It was to be a collection of portraits, fashion and advertising illustrations of Australian girls by professional photographers including Max Dupain, Athol Shmith, and Laurence Le Guay. "This exhibition promises to be one of the most outstanding events in the history of Australian photography for it is the first time that the outside world has had the opportunity of seeing Australian photographic illustrators' efforts together in one exhibition'.89

This magazine really tried to bring to notice non-Pictorialist photographic exhibitions, and to get amateurs involved. Le Guay believed that many 'so-called glamour photographers of the period were producing] images of stiff, bored models, without interpreting the subject matter. Young, vibrant models should not be represented as statues'.90 He explained that magazines like Vogue had displayed 'a more vital, stimulating and artistic collection of prints than those offered by many of the foremost "artist-photographers" of the exclusive salons'.91

Contemporary Photography was the first photographic journal in Australia that was not published by a photographic company, as the A.P.-R. had been since 1908. At the time, photography was not overly popular, there were paper shortages, and high printing costs associated with the war, but photography has since been accepted with its own criteria for good results, quite distinct from other media.92

CP was a journal for all manner of photographers, and its name described its contents well. The late 1940s was a transition period for photography, and the magazine was started in order to arouse a more general interest in photography in Australia—not just as an advertising tool or a Pictorialist pursuit in salons;93 it hoped to 'lead to a better understanding of the technique and art of the camera'.94

In the magazine's first issue, its purposes, aims and requirements were explained:95 that a magazine like this needed to follow the progress and development of photographic art, and preserve the works which were produced along the way—Le Guay stated that CP would be a record of the times. Despite the need for a magazine that did this and captured the mood, atmosphere and beauty of life and people, war rationing and the absence of professional photographers due to their enlistment in the war effort overseas, delayed the new magazine's appearance.

Le Guay stated that such a magazine should be representative of all the nation's photographers, both professional and amateur, and so the magazine's publication was dependent upon their return. CP was to feature die work of both, and hoped to allow the professional to display work and give details about how and why such images were created in order to set high standards for others, as well as provide the amateur with an outlet for their work, and helpful criticism and advice. Le Guay believed that this would steer them in the 'right' direction.

Richard McKinney described photography as a mixture of art and science, the sensual and the intellectual, in an article entitled 'Photography as an Aesthetic Medium'. He wrote that photography should not encroach on the painter's field of endeavour—photography's creativity comes in the selection of subject matter and the way it is presented, but should limit itself to depicting material phenomena.

He warned that photographs lose their inherent realism through 'too much creativity', becoming poor imitations of paintings. He believed it was possible to present photography creatively—with the proviso that practitioners stick to a truly photographic process, which included montage.96

Ruth Ann Curtis expressed frustration with the fact that the photography which was then being considered art was produced mainly in the darkroom, rather than through the lens of the camera out in the real world. She called for an adoption of naturalistic photography, in which the negative decides the appearance of the final print, not the handwork applied afterwards.97

A. Chambers also joined the art-photography debate, with an article in which she explained that in order to produce a work of photographic art, one must strive to surpass the ordinary — that not all photographers are artists, just as not all practitioners of other media are good enough to be called artists.98

Chambers wrote that since the turn of the century there had been a trend in art towards 'interpretation' rather than representational renderings of subjects, but photography was beginning to be recognised as having its own uses, style and appeal, and that it need not attempt to imitate painting, drawing or etching.99

In 1947 W. G. Ryall of Bellevue Hill wrote to the Editor of CP calling on amateurs to shake professional photographers from their complacency. The writer believed few had 'genuine regard for photography itself.. .most seem content to use the same methods and formulae proved obsolete some years ago'.100

It was a plea for more naturalistic photographs to be presented as art works, and for the irrelevant Pictorialism to disappear.

David Moore was a regular contributor of photographs to Contemporary Photography from 1948. He was influenced by the kinds of pictures Max Dupain was taking of the city, harbour, and the people when he was employed in his studio in the late 1940s.

He was also inspired by Carrier-Bresson's "decisive moment" and the spontaneity of his pictures taken roaming the streets, Brassai's surrealistic pictures of Paris, and Bill Brandt's social subjects, as well as the work of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange from the FSA project.

He was impressed by the realism of Documentary films like The River and The Plow That Broke the Plains by Pare Lorentz, and John Steinbeck's novels. Moore found that photographing the 'visual delights' of the streets and shores of Sydney was more satisfying than the shallow and artificial nature of the studio work he was doing for Russell Roberts.101

As a contrast to his upbringing in Vaucluse, Moore roamed the streets of Redfern, Surrey Hills, and other depressed areas photographing what he saw, often with his friend David Potts. Far from being a true Documentary photographer, his personal works were a project in aesthetic realism rather than social reform,102 nevertheless, his slum pictures have since become icons of the depressed life many lived after WWII.

|

|

|

Fig 13: David Moore Funnel of the 'Orion' (as appears in David Moore - Australian Photographer vol I, p.7);

a.k.a Ship Design c1948 (as it appears in Silver and Grey, plate 66);

a.k.a Composition in Curves (as it appears in Contemporary Photography March-April 1948, p25)

[Reproduced from Silver and Grey, plate 66] |

|

Fig 14: David Moore, Sydney Harbour Bridge 2 c1948;

a.k.a 9am Monday (as it appears in Contemporary Photography Sept-Oct 1948, p51)

[Reproduced from Sydney Harbour–David Moore, p32] |

Three of Moore's pictures appeared in the Print Analysis section of CP. He was fascinated by the dramatic forms of the ships that voyaged between Australia and Europe and the travel adventures they promised.103

Composition in Curves was the title given in CP to Moore's image of the Funnel of the Orion 1947 (which was also labelled Ship Design in Silver and Grey) [Figure 13]. Harold Cazneaux labelled it a 'straight forward modem' style of image but complimented it on the good composition which produced a splendid pattern.

It is one of the best essays in the way of a Modem Candid subject that can be easily missed out on, had not the photographer possessed the "seeing eye" and the quick mind to guide the camera lens to the correct position to secure such a striking and successful result. This is a picture well worth the front line in any salon.104

Moore's 9am Monday [Figure 14] was taken with a RoUeiflex camera, and was another of his that appeared in CP's Print Analysis section. Cazneaux was impressed by the photographer's technique and the results from the Modern Miniature Camera and described it as 'fine photography of documentary character and value'.105

The same photograph appeared in Sydney Harbour—David Moore as Sydney Harbour Bridge 2 1947. It is a stunningly clear record of rraffic conditions and car styles from the period but the composition, light and cloud effects, which mirror the pattern of cars converging at the bridge's arch, also make the image beautiful.

|

|

|

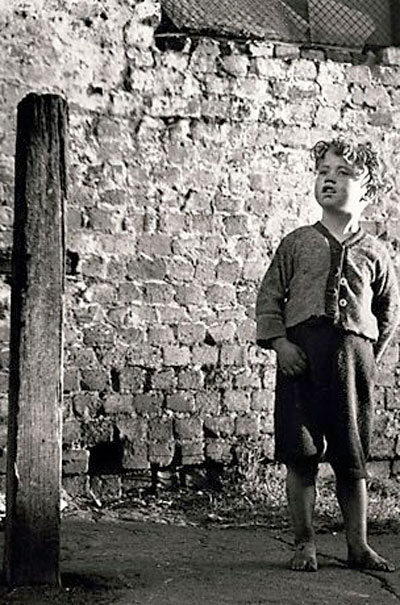

Fig 15: David Moore Little Charlie (cropped as appears in David Moore - Contemporary Photography May-June 1949, p21);

a.k.a Surrey Hills Boy 2 (as it appears in David Moore–Australian Photographer vol I, p24) ;

a.k.a Redfern Boy 1948 (as appears in Masterpieces of Photography, Joseph Lebovic Gallery) printed 1976

[Reproduced from Contemporary Photography May-June 1949,p21] |

|

Fig 16: David Moore, Emulation c1949;

[Reproduced from Contemporary Australian Photography Sept-Oct 1949, p18] |

Surrey Hills Boy 2—1948106 was labelled Little Charlie [Figure 15] in CP and Cazneaux described it as a candid style of photograph. He questioned whether the photographer's motive in producing such an image was to capture the effects of light and texture on the scene, or a concern for the future of the subject in his slum-like surroundings. He believed the clue to Moore's intention was in the photograph's title—that it roused the viewer's interest and sympathy, which placed it 'on a higher plane of pictorial expression'.107

He did not discuss any aesthetic content, and stated that the message was more of a concern in this context than art. Moore had a deeply emotional attitude towards the boy depicted in the image and his situation in life,108 but it displays a delicate quality of light, and the boy's expression adds extra visual interest.

Cazneaux's analysis revealed that naturalistic photography was assumed to have a social motive and that it could not be reconciled with the artistic motive. There was a distinct lack of critical approach for Naturalistic photography around this time. Other pictures with child subjects appeared in Contemporary Photography: Moore's Emulation [Figure 16] shows two boys in a deserted alleyway, apparently playing with a slingshot.

The title suggests an innocent childhood relationship, and does not comment on their social situation. David Potts's untitled picture [Figure 17] of a solitary boy in a dark alley is a more forlorn image; he is not playing, but there is a dog off in the distance, and he appears to be the same boy depicted in Moore's Surrey Hills Boy 2.

|

|

|

Fig 17: David Potts, Untitled c1949;

Reproduced from Contemporary Photography Sept-Oct 1949, p18] |

|

Fig 18: David Moore, Redfern Interior 1949;

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra [Reproduced from Sydney at Mid Century–40 Photographs by David Moore exhibition catalogue, plate 4] |

All three of Moore's photographs which appeared in CP's Print Analysis section have since had name changes. The different titles reflect the changing attitudes regarding what photographic captions should be. Romantic titles were favoured in the 1940s, as Pictorialist sentimentality was still influential, but after Moore was exposed to more international photography of quality in the 1950s, more direct and informational titles seemed appropriate.109

|

|

Moore's photograph titled Redfern Interior [Figure 18] shows a young mother (Mrs Eileen Dawes) nursing her baby, and an older woman (Mrs Annie Plummer) with her granddaughter (Carol Stanley) at her feet110 To capture this image, Moore used a quarter plate Speed Graphic camera with flashgun borrowed from Max Dupain, the kind press photographers used. He was mistaken for a newspaper photographer and dragged into the house by a Redfern woman and ordered to photograph the scene and publish it.

Moore believed the bedroom scene 'epitomised the plight of many slum dwellers'—he was told that three families were living together, the building had been condemned for demolition, and they were offered no alternative solution. He exposed two shots, one became Redfern Interior and the other was a wider shot including the woman who pulled him in to the house and two boys at the door, all to the viewer's right of the now-famous old woman.

After having pangs of guilt for invading these people's lives under false pretences, Moore considered destroying the image, but Dupain convinced him to keep the negatives of the Redfern scene because they were important. Moore sent the prints and details of the situation to the Municipal Council with a plea for them to be considered before eviction, and this helped clear his conscience about having little means of publishing the images as the Redfern woman wished.111 |

Fig 18a: David Moore, Mother and Child 1949;

[Reproduced from A Portfolio of Australian Photography,

plate 67] |

|

Moore showed the picture, with others, to Le Guay, but when Redfern Interior appeared in CP as only half the original image, showing just the old woman and child on the floor [Figure 18 (a)], Moore wrote to Le Guay to ask for his policy on cropping, explaining that when photographs are published as art (as they were in CP), they should have precedence over any layout considerations, because they are considered efforts of self-expression.

He wrote that cropping in publication altered the meaning as well as the aesthetics of an image.112 In CP, the cropped image was published as an example of the Naturalistic style of photography which emphasised the photographer's sympathetic understanding of the subject, focussing on the woman's stare into the distance and the child's yearn for attention and look of wonderment—a distinctly different purpose than it had originally been intended (which was to expose an injustice).

In 1948, Contemporary Photography featured Harold Cazneaux's (1878-1954) reprinted old negatives (which dated back as far as 1904) in a section entitled 'Sydney of Yesterday'. They were described by Le Guay in an Editor's Note as being of great 'pictorial and documentary value to Australia', and were reprinted ultilising the recent technological advances of modern enlarging papers instead of the old bromides.

Cazneaux himself noted his amazement at the quality of his images when compared with the soft, delicate negatives from which they were printed.113 Cazneaux's Midge Box camera allowed him to wander Sydney streets and capture his vision of life and express it creatively, although his pictures were originally printed more as 'impressions' than records in the Documentary genre.114

In the accompanying article, Cazneaux noted the changes to the city of Sydney since the photographs were taken. He explained that it was his dissatisfaction with the work he was doing in a commercial studio which led him to photograph the subjects he did. He compared the availability of photographic equipment then to the situation in 1948, and noted the advantages of the discrete nature of the miniature camera for exploring alleyways.

Cazneaux expressed his lamentation that galleries had not recognised the works by Arthur Ford and Cecil Bostock of the old Sydney: 'it is indeed a sad affair that such pictures have no permanent home such as our National Art Gallery'. However, Cazneaux saw their value for collection as historical, rather than artistic. Australian art institutions did not yet collect photography as art, and perhaps the value of such photographs as documents was pushed in an attempt to change this state of affairs.

Le Guay suggested that Cazneaux's prints be collected by the Mitchell Library or Australian Historical Societies because they were valuable prints of the period. He also noted the quality of the pictures, considering the slow speed of lenses and cameras at the time and hoped that the reprinting of these old masterpieces would inspire a 'more direct and accurate approach to photographing Australia today'.115

They were utilised for the current trend of Naturalistic, sharply-focused images of real life, to be contrasted against the Pictorialist taste for idealisation. This project provided an Australian past for the Documentary aesthetic favoured by most photographers who contributed to CP in the late 1940s. Cazneaux's pictures were originally printed in the Pictorialist style and were adapted to fit in to Documentary's preference for human interest. Newton recognised the change in Cazneaux's pictures, from the old prints in which the human interest factor was less noticeable.

In an exhibition of Cazneaux's works at the National Library of Australia in 1996, his attitude to the camera was stated as a tool 'to be used on the way to a final image'.116 He was positioned as Australia's foremost Pictorialist—a more accurate description than where he was positioned in the late 1940s.

Cazneaux's main body of work was produced in reaction to the sharp-focused approach of commercial photography at the turn of the century in an effort to be artistically expressive in photographs. Pictorialism was considered avant-garde in those days, but in 1951 he acknowledged that 'the romance and the spirit of the Pictorial movement is no more'.117

- Interview with Laurence Le Guay from De Berg Tapes, 'Laurence Le Guay', 2 March 1976, Oral History collection, National Library of Australia. Contemporary Photography became the official publication of the Institute of Australian Photographers from May 1948 (aiming to 'raise the standards of photography throughout Australia', Russell Roberts was President, and Laurence Le Guay was Vice President). The magazine was also the official journal of the Professional Photographers' Association of Australia from mid-1949. In March 1948, J. A. Parkinson became Assistant Editor, and in September 1948 Cazneaux became a Consulting Editor. In an Editorial (CP May-June-July-August 1949, pi 1), Le Guay explained the growing popularity of the magazine and the mass of correspondence, culminating in the realisation that 'running CP is everyone's business'.

- Conversation with Candy Le Guay 29/8/96 and with David Moore 26/8/96.

- Hall and Mather, Australian Women Photographers, p90.

- W.H. Moffitt, "The Status of Pictorial Photography', in A.P.-R. May 1947, ppl 14, 240.

- Newton, Shades of Light, pl 14.

- Moffitt, 'Status', p240.

- Ibid.,pp240-l.

- Ibid.,p242.

- Ibid.,p255.

- Edward C. Partridge, 'New Ideas Behind The Camera' reprinted from Amateur Photographer May 30,1951,

in A.P.-R. November 1951,pp665-7.

- Peter D. Snow, article reprinted from Amateur Photographer August 15,1951, in A.P.-R. November 1951,

pp665-7.

- Author not named, 'Pictorial Photography in the Doldrums' from British Journal of Photography July 1954,

in A.P.-R. December 1954, pp758-9.

- Newton, Shades of Light, p123.

- Ibid., pi 18.

- De Berg interview.

- Conversation with Candy Le Guay 29/8/96.

- Newton, 'Pictures in Print', Australian Photography—A Contemporary View, Sydney, 1978, unpaginated.

- Allan Sekula, 'Photography Between Labor and Capital' in Leslie Shedden, Mining Photographs and other Pictures 1948-1968: A Selection of the Negative Archives of Shedden Studio, Glace Bay, Cape Breton, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1984, pp243-5.

- In CP March-April 1948, pp39 and 16.

- Le Guay, Editorial, CP May-lane 1947, p7.

- Willis, JM, p193.

- Colin Peebles and John Sandes, 'The Professional Amateur', CP May-June 1947, p12.

- Author not named, 'The Photographic Societies' section of CP Nov-Dec 1947.

- Laurence Le Guay, Editorial, CP January-February 1948, p8.

- Laurence Le Guay, Editorial, CP May-June 1948, p10.

- De Berg interview.

- Conversation with Candy Le Guay 30/8/96.

- Laurence Le Guay, Editorial, CP November-December 1947, p8.

- Laurence Le Guay, CP November-December 1946, pp 63-4.

- R. McKinney, 'Photography as an Aesthetic medium'. CP, Nov-Dec 1946, pp58-9.

- Ruth Ann Curtis, 'Art and Photography: Which Is Which?', CP May-June 1947, p49.

- A. Chambers, 'Photographer or Artist?' in CP March-April 1948, p13.

- "Ibid.,p66.

- w. G. Ryall, 'Open Shutter' (Letters to the Editor), CP Nov-Dec 1947, p53.

- David Moore, David Moore—Australian Photographer vol.1, Sydney, 1988, p24.

- Letter to Gael Newton from David Moore, 1987, David Moore file at NGA.

- Moore, David Moore—Australian Photographer vol.1, p6.

- Harold Cazneaux, 'Print Analysis', CP March-April 1948, p24.

- Harold Cazneaux, 'Print Analysis', CP September-October 1948, p50.

- As it appeared in David Moore: Australian Photographer, vol.1, p24.

- Harold Cazneaux, 'Print Analysis', CP May-June 1949, pp20-l.

- Conversation with David Moore 9/10/96.

- Phone conversation with David Moore 9/10/96.

- 'Snapshots of a Suburb Revisited' by Carmel Egan, The Weekend Australian June 17-18 1989, pi and 5.

- This account of the circumstances surrounding Redfern Interior appears in a letter from David Moore to Gael Newton, dated May 1987, in David Moore file in NGA.

- Moore, David Moore—Australian Photographer vol.1, p24.

- Harold Cazneaux, 'Sydney of Yesterday', CP May-June 1948, p26.

- Newton, Silver and Grey, Introduction, unpaginated.

- Laurence Le Guay, Editor's Note in CP May-June 1948, p32.

- Harold Cazneaux—Photographs exhibition panel, National Library of Australia, 1996.

- In a letter to Jack Cato, cited in Sally Webster, Harold Cazneaux—Photographs exhibition catalogue, NLA, 1996, unpaginated.