Chapter One: Documentary and Pictorialism

The period spanning the 1930s to the 1950s saw several important technological developments in the area of photography. Small-format cameras like the Leica were becoming popular with reporters in the 1930s because they were much more mobile than the heavy cameras that needed tripod support, and they allowed photographers to move into areas of the city where discretion may have been desirable; faster lenses and films made the dangerous flash equipment of previous decades unnecessary, and allowed photographers to take more unposed shots and capture the action of real life outside the studio in faster exposures and more often in natural light.22

Henri Cartier-Bresson's concept of the "decisive moment" described a style of photography which pitted itself against Pictorialism's concentration on creative effects produced on the photographic print, and instead utilised the photographer's quick recognition of a scene captured on the negative with aesthetic and personal expression. In the post-WWII period, the practice of coating lenses with metallic vapours was mastered as it was found to increase the speed of the lens as well as improve definition and depth of focus.23

This influenced the move of art photography away from Pictorialist renderings. The new technology freed the photographer to concentrate on aesthetic concerns when capturing the image on film rather than dealing with the mechanical "restrictions" of the camera's operation. Photographers could now more easily and accurately express themselves photographically rather than with handwork on the processed print.

In the 1930s Pictorialism was deemed unphotographic by photographers who wished to use the medium's technology to produce images of aesthetic appeal without imitating other media. Pictorialists considered the photographic process to be only an intermediary tool on the way to the production of an artwork, but the f/64 group in the United States in the 1930s wanted to prove that the photographic process could yield beautiful and unique images, by emphasising the camera's clearly focused rendering of a scene.

Around the same time, the New Photography (or Modernist photography), which was influenced by the German Neue Sachlichkeit movement in art, also reacted against Pictorialism's view of photography.by emphasising the beauty of form-in-itself. Aspects of this style were more commonly seen in photographic advertising and other commercial work than given recognition as a legitimately artistic style by the amateur photographic salons of the day.24

The experimentation of Modernist photography in the 1930s was disrupted by World War II, due to rationing and Australia's termination of the importation of good cameras and lenses from Germany. Many freelance photographers were also squeezed out of work by the proliferation of propaganda photographs available from the Department of Information' s photographers.25

In light of the advances in photographic technology, Le Guay warned camera users against a complacency which would turn photography into an automatic process. He called on photographers to study the work of past masters for inspiration and insight into correct technique, because only then could photographic technology be used to its full potential.26

Despite the new subjects that became possible for photographers with better equipment, and the use of photography for raising awareness of social problems, traditional artistic principles and composition were still believed to be important. There was a widespread move against Pictorialism towards what was often called a 'Documentary' style, but with an emphasis on composition and print quality aiming to produce photographs worthy of exhibition in art galleries.

Australian photographic history lacked a social reform movement on the scale of the American FSA of the 1930s,27 but the work of Australian photographers in the Department of Information (DOI) in WWII can be compared to the American Office of War Information's propagandists uses of photography.

The 1930s to the 1950s saw the height of the popularity of the Documentary philosophy, as it was used by governments as a tool of persuasion and propaganda to rouse support for their policies and programs, as well as a tool for record-making in times of enormous social upheaval and change. Ever since the photographic efforts of the FSA, the term "documentary" has been associated with that practice—perceived as a strange mixture of institutional manipulation, and concerned altruism.

The Documentary aesthetic was adopted by mainstream photographers after WWII, as they used photography to depict society in a realistic and vital way, but mostly without the strong political concerns of the photo-reformers who had used a straight-approach to photography since Riis in the 1880s.

The photographers working for the Australian DOI (1939-41) and the public relations department of the Allied Works Council were quite influential in altering photography's status after the war, and in the move towards a non-Pictorialist photographic art. WWII photographers were trained in practical areas of photography and returned to civilian life with a 'harsher' vision of life.

The commercial photographic field extended during this period to include technical, industrial, illustrative, fashion, and advertising areas, and these professional avenues for photographers certainly influenced the style of photography being considered creative or artistic in the following decades.

Geoffrey Powell (1918-89) was a socially-concerned photographer who believed photography should be used as a social weapon with a Documentary approach.

In an article which appeared in Contemporary Photography, he wrote that the popularity of photography as a reportage medium and the idealisation of professional studio portraiture had contributed to the trivial use of the camera.

Despite important technical improvements in the field of photography—which resulted in sharper images and richer prints, 'the standard of photography today as an interpretive medium has degenerated from an appreciated art to a discounted pastime.28

He wanted to see photography used for more important social causes, 'positive interpretations of society's ills and troubles', rather than glamour, advertising, and the general escapism which he believed characterised commercial photography and the images used in picture magazines.29

The article included two of his own photographs.

Family Group [Figure 1] shows two women and five children huddled outside on a verandah with part of a pram in view. The photograph has been shot from below which gives the group an air of dignity. They appear to be unaware of the photographer's presence, looking up and to the photographer's left.

Powell casually referred to this image as 'Family Awaiting Eviction... 'in 1988,30 and it was awarded a bronze plaque in Australian Photography 1947. The other picture, Truants [Figure 2], shows two boys sitting outside reading a comic book with the company of a cat. Their dirty and scruffy appearance suggests they are from the more down-trodden of society, but the title suggests that they are just skiving off and enjoying themselves instead of doing what they are supposed to.

Far from just a political activist for social reform, Geoffrey Powell became involved in the debate about photography being considered an artistic medium. He wrote at least two articles in the left-wing journal Progress about his ideas of photographic art, and the need for photography to break away from the emulation of other graphic media as a true means of creative self-expression. He also called for exhibitions of the best photographic art to be held in places where ordinary workers gathered instead of being confined to esoteric salons and exhibitions.31

He felt that 'the more constructive purpose of helping mankind' was what photographers should aim for, and that Australian photographers should have more respect bestowed upon them, and be credited for work published in picture magazines.

He also believed the use of photography during WWII had brought photography out of its shell, to encourage more uses than just snapshot records.

His untitled photograph for this article was later reproduced in Australian Photography 1947 as Delegates at a Political Conference [Figure 3].32

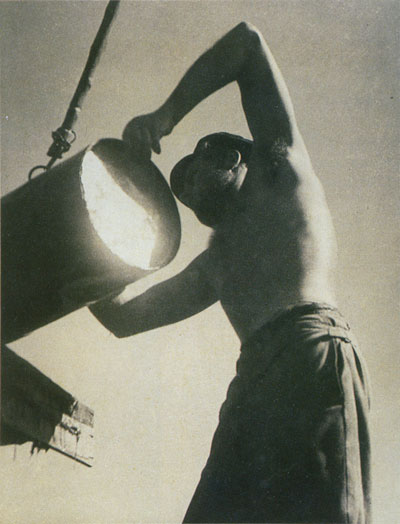

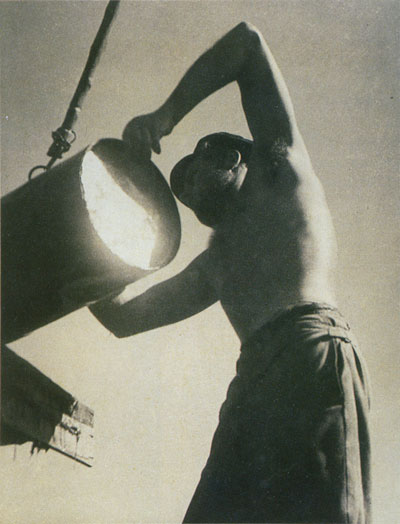

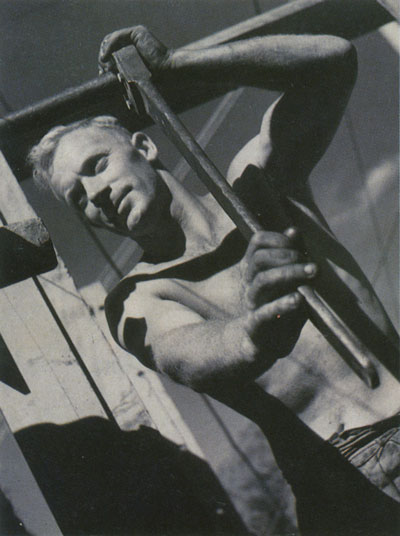

Powell's Bailing for Water c193833 (named as Self Portrait Boiling Water, 1947 in Shades of Light) [Figure 4], is reminiscent of the style of Edward Cranstone's government-commissioned photographs, with its emphasis on the form of the human body.

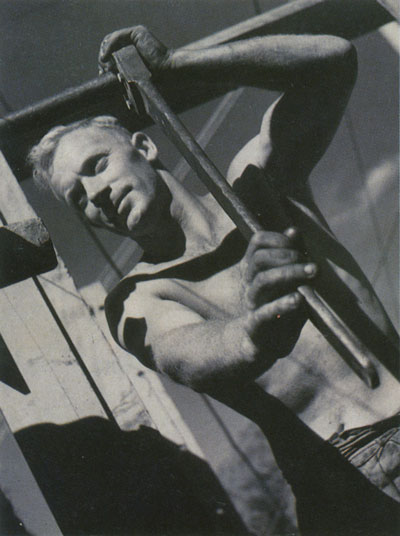

Masculine strength, photographed in-action, highlighting the outdoor activities and the harsh sunlight, is typified by Cranstone's Civil Construction Corps Worker c.1943 [Figure 5].

He concentrated on the form and graphic shape of his subjects, which tended to heroise workers in their encounters with machinery, in a similar manner to Soviet Social Realist art.34

Helen Ennis has written that Powell was a difficult character to assign the title of photographic artist to, as much of his work was commissioned, and appeared mostly as reproductions in newspapers, making it difficult to view them as works of self-expression.35

However, socially-oriented photography like his played a part in photography's wider acceptance as an art practice, beginning in the 1950s. The fact that some of his works have appeared in Australian photographic histories since, and photographic journals and annuals at the time, suggest that Powell was more than just a political photographic reporter.

Edward Cranstone (1903-1989) worked as a photographer for the Department of Information in the photography unit of the RAAF during World War II. His photographs were used by the government to publicise Australia's war effort in newspapers and exhibitions. In particular, he documented the work of the Allied Works Council (AWC) and the Civil Construction Corps (CCC).

Several of his AWC and CCC photographs were reproduced in Contemporary Photography magazine in January-February 1947,36 with an accompanying article which explained that the travelling exhibition of these prints in 1944 (called Design For War, and included 500 of Cranstone's pictures and paintings by Dobell and McClintock)37 provided the public with a truthful account of the CCC's work, in contrast to the "false" impression provided by news reports.

Here, photography is placed in an evidential role, as more valuable than written accounts because they were believed to be less open to misinformation and false impressions. |

|

|

| |

Fig 1: Geoffrey Powell, Family Group 1945 (also appreared in Contemporary Photography November-December 1946, P17 - Reproduced from Australian Photography 1947, P49) |

| |

|

| |

Fig 2: Geoffrey Powell, Truants c1946 (also appreaded in Contemporary Photography November-December 1946, P16 - Reproduced from Australian Photography 1947, P44) |

| |

|

| |

Fig 3: Geoffrey Powell ,Delegates at a Politicial Conference, c1945 (Reproduced from Australian Photography 1947, P171) |

| |

|

| |

Fig 4: Geoffrey Powell,Bailing for Water, c 1938; aka Self Portrait Boiling Water 1947; Reproduced from Shades of Light, p128 |

| |

|

| |

Fig 5: Edward Cranstone, Civil Construction Corps Worker c1943; from his album Design For War Vol. 1; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra - reproduced from Shades of Light, p.128 |

All of his assignment pictures were taken with a Rolleiflex camera in natural light, and are evidence of the effect technology (and the equipment restrictions that applied for DOI photographers due to weight) had on the style of photography. The government's aim for such assignments was to document the work for posterity, and consequently, only a small amount of the huge volumes of images were actually published during the war.38

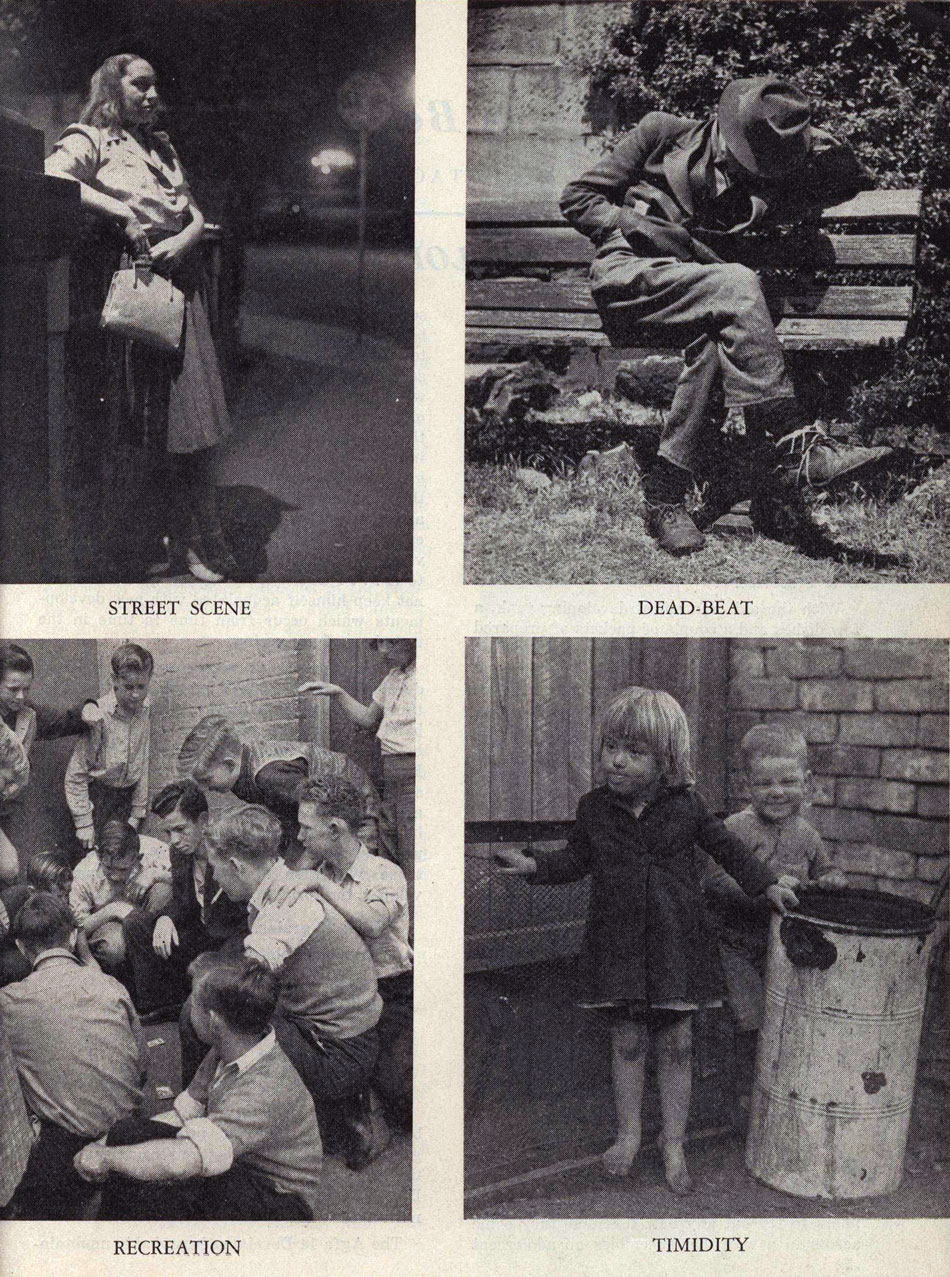

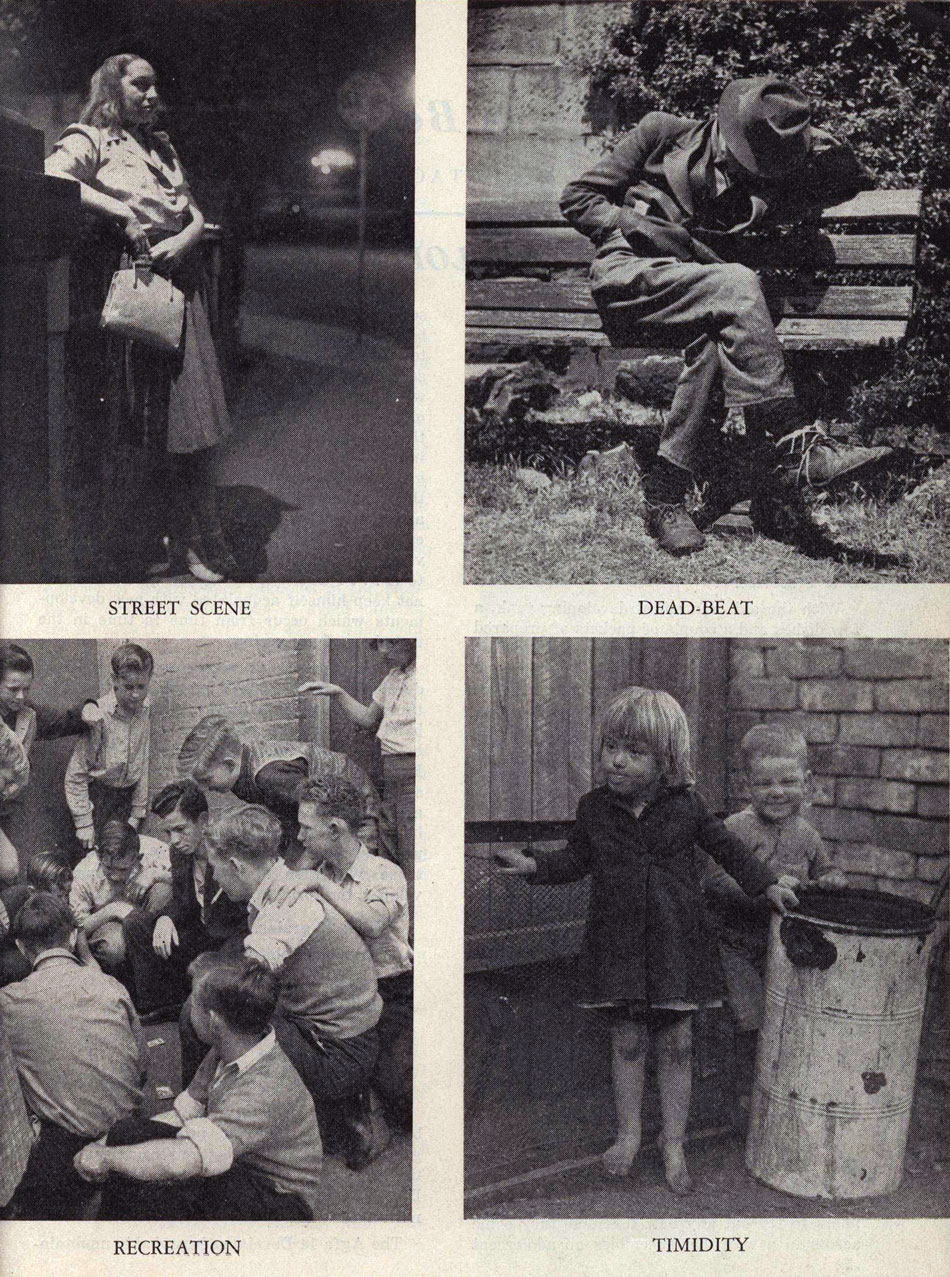

Several of Cranstone's personal (or non-commissioned) photographs were also published in Contemporary Photography (March-April 1947) as "documentary" images of the people and streets of Sydney.

|

| |

|

Fig 6: Edward Cranstone, Titles as listed c1947; reproduced from Contemporary Australian Photography, March-April 1947, p51

|

They were positioned as universal features of urban life, and were accompanied by a comment that photographs such as these argued for the abolition of such living conditions. They had titles like: Timidity—showing a bare-foot little girl outside with a boy next to a rusty drum, Dead-Beat—a man asleep sitting up on a park bench, Recreation—a group of well-dressed adolescents playing a game, and Street Scene—showing a solitary woman at night [Figure 6].

However, these titles are not specifically descriptive and do not provide information about the subjects or location. The images appeared more as social studies and depictions of the human condition rather than specific injustices in the manner of Hine's Documentary social-reform photographs.

Cranstone later revealed that such photographs were intended to make up a book 'with a social slant' of the conditions of the underprivileged classes in Sydney.39 He believed he needed to do something to fix what was wrong with society,40 but the book never eventuated.

Cranstone's What of the Future? [Figure 7] appeared in Contemporary Photography to illustrate Frederick George's call for the photographic recording of the crumbling chaos of city life:41 it shows three children sitting on a step—the boy on the left is quite clean and well-dressed, the girl in the middle is bare-foot and matt-haired, and the boy on the right appears to have just eaten, with a dirty face and hands and a bib around his neck.

Judging from Cranstone's desire for these pictures to be compiled into a book, this image was an emotive call for social reconstruction, however, the article made no mention of the use of photography to attempt to cure these problems. Instead, George's concern was that universities, the National Library and the Education Department take up the task of compiling a pictorial national archive of the major incidents in Australia's rise to nationhood.

The style of photography which used the underprivileged classes of subject matter was generally labelled 'documentary', whether it was intended to be a political image or not. |

|

|

| |

Fig 7: Edward Cranstone, What of the Future? c1949;

reproduced fromContemporary Australian Photography, September-October 1949, p18 |

Due to the cumbersome nature of cameras at the turn of the century, slow lenses, and poor flash equipment, which limited a photographer's mobility, Pictorialist subject matter usually consisted of moody, uninhabited landscapes or romanticised studio portraits.

The end result of a photographic image was altered to a more expressive and atmospheric impression of a scene or subject by the use of a number of printing processes: gum bichromate, carbon, carbro, and bromoils, as well as retouching the negative and/or print.

The premise behind the Pictorialist approach was that reality needed improvement in art images, and many methods were used to construct an idealised picture, including concealed montage: cloud details were often added to an image by combining two negatives. Laurence Le Guay promoted the use of photo-montage as an advertising tool for displaying a product's best qualities in a single image, but differentiated it from its Pictorialist uses.

Montage used 'for its own sake.. .producing an artistic result' was considered more "honest" than Pictorialist mood-creation that was passed off as 'a true exposure of the scene'.42

Several of Le Guay's montage photographs were published in Contemporary Photography: a wrist-watch was overlayed with an hourglass; a portrait of a girl gazing into the distance was superimposed on a night-time scene of the Sydney Harbour Bridge; an automobile wheel and hubcap were added to the corner of an image of a cartwheel—and an article accompanied them to explain how these images were created.43

Pictorialism was the only style and approach really recognised as artistic by traditional photographic salons, and was characterised by soft-modelling on subjects and filtered sunlight. Practitioners prided themselves on the 'delicate separation of planes' in their images compared to the flatness of Modernist photography,44 but Australia's stronger light made Pictorialism more difficult than in the soft atmosphere of Britain and Europe.45

The New Photography style was accepted in Australian salons in the 1930s, and photographers like Max Dupain adopted this approach in a lot of his work, but 'the Pictorialists did not extend any special recognition to Dupain or any of his contemporaries'.46

Dupain formed the Contemporary Camera Groupe after the 1938 salon of the Photographic Society of NSW when he came into conflict with the judges, whom he criticised for accepting "flaccid" traditional European-style works instead of contemporary works which have explored the aesthetics of abstraction.47

Le Guay criticised post-WWII salons for not displaying the vitality and new creative spirit expected considering the experimentation of before the war, and believed Pictorialist photography had stagnated. He called for the end of photography's reputation as 'a mechanical and basely imitative form of art', particularly when modern equipment had freed photographers from complicated technical considerations.

He thought that the photographs appearing in the new salons were too adulterated and lacked the spontaneity of vision that was possible with the equipment. Photographers 'should endeavour to develop a faculty for seeing and preserving the real yet commonplace events.. .In the average salon there are still too few glimpses of reality through the personal interpretation of the photographer'.48

Although the standards set by contemporary salons are more photographic and less expressive of the period which pandered to veiled diffused "nudes", and overdressed "character studies", there is still too much artificiality and too little personal interpretation of life in the great majority of prints submitted to present-day salons.

Clean photographic quality and a not too arbitrary regard for composition are still essential to good technique and good taste. But the quality, crispness and spontaneity of vision, made possible by modern equipment, is too often misdirected and adulterated in preparation for todays salons.49

Articles which described Pictorialism's development as 'bogged', even began to appear in photographic journals which were known to advocate the Pictorialist approach to photography. The term 'pictorial' was used to describe a style of photography which rejected photographic realism. There was a call for the broadening of the concept of what was considered artistic photography.

Peggy Delius explained that although the Royal Photographic Society's policy was to hang works of pictorial merit only, this need not mean soft-focus painterly images, and that there was no reason why the photographic picture, showing every aspect of life should not indeed be recognised as pictorial.. .the method of production, the specific technique employed, matters not one iota; the sincerity of purpose and honesty of execution by whatever means employed will always essentially decide the real worth of any visual work of art...the result matters, whether it convinces and thrills you. If it satisfies your emotions and your judgement, that picture is truly pictorial.50

The emphasis placed on 'pictorial' work by most camera clubs was criticised in an article in Contemporary Photography entitled 'Broaden Your Outlook (A Suggestion that Camera Clubs are Not All they Might Be)'.

The writer believed that avenues other than salon selection should be pursued, and asked why photographs could not be judged on 'technical work, on impact, on faithfulness to original subject or mood', without being considered merely a record.51 This was a call for the removal of the stigma attached to photographic realism.

Dr Julian Smith's character studies were featured in Contemporary Photography (March-April 1947) with an article explaining his technique. He wrote that 'when the results are convincing, they are apparently very popular with the general public'.52 He was prominent in the 1930s and 1940s, and gained international recognition with a feature of his work appearing in American Annual of Photography in 1941.

The popularity of this style of work is evidence that the 1930s were not dominated by the style of the New Photography. Smith's photography was very much of the Pictorialists style, as he favoured posed, soft-focused, romanticised interpretations of historical figures and character types. An example of the convincing quality of his work is the 'Falstaff character, which was captioned Is not the Truth the Truth [Figure 8].

Despite the success of several photographers working in the Pictorialist style, photography was attracting many more new-comers who tried to imitate the style of these Pictorialist masters. In 'An Axe to Grind', Joe Mitchell wrote of the stagnation of photography in photographic societies that continue to exhibit the same hackneyed treatment of the same wearied subjects that were exhausted way before the last war... Too often do workers follow the well-trodden tracks of composition and copy the ideas of others, instead of striving for some entirely original interpretation.53

Answering the Pictorialists who criticised modem photographic papers for displaying too-few tonal variations, Mitchell explained that 'so few workers use the really magnificent range of tones which the modern bromide emulsion is capable of rendering'. He emphasised the importance of photographic skill, for which no amount of technology could compensate,54 and his solution to the problem of the attitudes in the photographic societies was to encourage young photographers to join in and rejuvenate the system of analysis and judging.55 |

|

|

| |

Fig 8: Dr julian Smith, "Is Not The Truth The Truth" c1947 (Reproduced from Contemprary Photography March-April 1947, p36) |

In the early 1950s, Australian photographers were frustrated with attempts to have their work displayed in salons, as is evidenced by the articles which appeared in photographic journals. It was acknowledged that 'the salons continue, but the younger generation is seeking different forms of expression and leadership in a different direction'.56

Australian readers were instructed on how to produce prints which would stand a good chance of being accepted by the photographic salons. This article was reprinted from an American magazine, but the editor of A.P.-R. deemed it relevant to the Australian situation.57

It warned against the use of bizarre combinations of objects in the New Photography style, and advised that original presentations of familiar subject matter would rate a good chance. The writer stated that his aim was merely to instruct on the making of images deemed acceptable by the salons of the day rather than to clearly defend or criticise them in this time of re-assessment; nevertheless, it contained a twinge of criticism about the conservative nature of salon judges.

The article encouraged photographers to improve their landscapes by waiting until a good cloud formation developed, or to use filters to enhance any sky details, but made no mention of Pictorialist montage. It warned amateurs away from imitating other photographers' character studies, as they must appear natural to avoid an obvious shot of uncle Charlie dressed up as a pirate or an Arab, or some other unlikely personality.

The writer explained that successful character studies were made with the purpose of representing a common idea about the look of character types—not to dress any old person up in a costume for the purpose of a photograph. The article also encouraged the use of sharp focus as a move away from studio portraiture, and marks a gentle turning away from Pictorialist values.

Despite growing criticism that photographic society salons were becoming irrelevant to the young and progressive photographer, Laurence Le Guay called for their better utilisation. He warned that the salon was in danger of becoming an 'outworn institution',58 and needed to be more flexible and open to other styles of photography if the medium was going to develop and provide photographers with a suitable outlet for their artistic efforts.59

By criticising the maxims of salons, Le Guay believed a better understanding of the camera and photography as a distinct art medium would result. The salons needed to be challenged, although they were not the only places where top photographic art was to be found—the photographic exhibitions held in New York's MOMA under Steichen's direction were deemed very important for photography's development.

Le Guay distinguished between the nature of prints displayed at such exhibitions (where photography utilised its process as a means of expression) and the salons (where 'phoney subjects [are] rendered in a pseudo-artistic manner'). He pointed out that many professional photographers did not exhibit there at all, and that the salon should not be the ultimate aim of a photographer as there were other avenues waiting to be explored.60

He believed many of the best forms of photographic art were to be found as advertising, industrial, and other work not yet deemed acceptable by the photographic societies, but in American magazines like Life, Fortune, Vogue, or Harper's Bazaar. Le Guay valued the existence of salons for the encouragement they provided for amateurs and professionals who believed in photographic art, but felt international salons could have been more fully utilised as important sources of information about the standard of overseas photography to an isolated country.

The only international photographic salon held in Australia at the time was the Adelaide exhibition (which turned international in 1945),61 and Le Guay proposed the idea of an Australian Salon of International Photography which would be exhibited on a national scale.62

As well as publishing written criticism of salons, Le Guay actively sought to teach photographers ways of bringing a vitality back to photography. He was one of the foundation members of The Miniature Camera Group of Sydney, which was formed in 1938 to encourage high standards in informative, educational, and cultural photography; to 'cultivate a fresh and original approach to the craft of picture-making'.63

It was formed to allow small-format camera enthusiasts to compare work and 'express themselves in ways other than what is usually called pictorial photography'. The group's first exhibition was held in 1940 at the Blaxland Gallery in Farmer & Co. department store, and by 1948 the name had changed to The Camera Club of Sydney to more accurately describe the size of the club and to remove the restriction on negative size.64

It was reported in Australasian Photo.-Review that Le Guay addressed the club in 1951 about his recent overseas trip and the trend in Europe towards a more factual approach to photography (along with abstraction), however, he noted that American photographic competitions were more conservative in approach. Interestingly, though, in the same report about the club, it was noted that H. P. James demonstrated the technique of montaging separate cloud and landscape negatives to produce an 'authentic' image in the manner of Pictorialism.65

These two speakers represented two different directions distinguishable in Australian photography at this time, and alerts us to the fact that there were still differing approaches to photography in the early 1950s. Amateurs were still intent, on the whole, of imitating past Pictorialist masters, especially in landscape photography.

However, photographers like Le Guay played a large role in educating amateurs to be more progressive and spontaneous in their endeavours. Le Guay again lectured at The Camera Club of Sydney, in July 1954, to explain why and with what techniques his well-known images were produced. The reporter seemed surprised that such large prints were produced from miniature negatives,66 which was a sign that technology was allowing photographers to achieve good print quality whilst being more mobile.

- Ibid.,p169.

- Eric Bierre, 'Modem Improvements in Lenses', in Contemporary Photography, Nov-Dec 1946, pp18-19.

- Newton, Silver and Grey, Introduction, unpaginated.

- Barbara Hall and Jenni Mather, Australian Women Photographers 1840-1960, Richmond, Victoria, 1986, pp90, 93.

- Laurence Le Guay, 'How Far Have We Really Come?', in Contemporary Photography, Nov-Dec 1946, pp65-7.

- 'Where the amateur movement had stimulated art photography during the Pictorialist era, it played virtually no role in the 1970s push for the recognition of photography as art', Willis, Picturing Australia, p191.

- Geoffrey Powell, 'Photography—A Social Weapon' in Contemporary Photography Nov-Dec 1946, 16

- Powell, 'Social Weapon', pp16 and 60.

- In a letter to Gael Newton 26/8/88, folio20 in Geoffrey Powell file at NGA.

- Geoffrey Powell, 'Are Photographers Artists?', Progress 5 October 1945, p9.

- Geoffrey Powell, 'Camera Art', Progress 7 September 1945, p17.

- Letter to Helen Ennis from Geoffrey Powell, in the Powell file at NGA.

- Willis, Picturing Australia, p188.

- Helen Ennis, 'Geoffrey Powell: A Worker Photographer', a paper for the Art Association of Australia Conference, September 1991, f54 in Powell file NGA.

- Edward Cranstone/Documentary Assignment', CP Jan-Feb 1947, pp8-11.

- The archives of Cranstone's exhibition photographs are held at the NGA.

- Interview with Martyn Jolly, Cranstone file NGA, folio25.

- Jolly Interview, f29.

- Jolly Interview f27.

- Frederick George, 'The Camera as Historian', in CP, March-April 1947, pp48-9.

- Laurence Le Guay, CP March-April 1947, p26.

- Laurence Le Guay, 'Photomontage', CP March-April 1947, pp24-27.

- James Hoey, 'Pictorial Photography—My Outlook and Method of Working', in APP, July 1962, p21.

- J. R. T. Richardson, 'A Photographer Emigrates', CP Jan-Feb 1950, p13.

- Newton, Silver and Grey, Introduction, unpaginated.

- Keast Burke, an extract from a speech for the opening of Photovision 1962, printed in APP, July 1962, p42.

- Laurence Le Guay, Editorial, CP March-April 1947, p9.

- Ibid., p9.

- peggy Delius, The Institute of British Photographers Record Nov-Dec 1944, reproduced in A.P.-R. May 1945, p228.

- A. Chambers, CP Jan-Feb 1948, p25.

- Dr Julian Smith, 'Character Study', CP March-April 1947, p36.

- Mitchell, 'An Axe to Grind', CP September-October 1947, p10.

- Ibid., pi 1.

- Ibid, p68.

- George B. Wright, 'Photography in Mid Century', American Photography January 1951, p20.

- Jack Wright, 'A Technique For Salon Acceptance' from American Photography July 1950, in A.P.-R. July 1951, p42

- Laurence Le Guay, 'A Note About Salons', in Contemporary Photography, Jan-Feb 1949, p13.

- Susan Sontag, On Photography, London, 1978, p148.

- Le Guay, 'A Note About Salons', p15.

- The Adelaide international photographic salon 'meritoriously held the fort for a number of years until running costs made the venture too onerous', but in 1949 there were no annual international photographic exhibitions held in Australian capital cities. [Leo Lyons, 'The Salon—International Photographic Art?', A Portfolio of Australian Photography, 1949, pxviii.]

- Laurence Le Guay, 'The Salon as Criterion' in CP Nov-Dec 1946, p32.

- Club Report, CP, Jan-Feb 1947, p66.

- Article by Cliff Nobel, in CP June-July 1950.

- Club Report, A.P.-R. April 1951.

- Club Report, A.P.-R. September 1954, p524.