In 1983 Anne-Marie Willis said, of the producers of a contemporary Australian Photography Yearbook6, that ‘if they survive past two issues, they will beat the record, as the history of Australian photography is littered with failed attempts to produce annuals.7 Although not actually yearbooks, the first attempt to regularly anthologise contemporary Australian photography were Cecil Bostock’s Cameragraphs. The two volumes emerged in the mid twenties based on the first two Australian Salons.8

In 1947 the photographic industry was commercialising and aestheticising the advancements in photographic technology that had been necessitated by the Second World War. Two influential schools of practice existed in Australia at the time. The Pictorialists were the old masters, carrying on a British-influenced style pioneered at the turn of the century. The young commercial photographers who had set up studios in the mid thirties followed more recent European and American ideas as well as British photographers such as Brandt. The presence of European refugees, experienced in the teaching s of modern photography, established an active discourse among the modern photographers.

Both schools had their own journal. The Pictorialists were served by Kodak’s A.P-R (Australasian Photo-Review), which was in its fifty-fourth year by 1947. The moderns had Laurence Le Guay’s one year old Contemporary Photography to exchange methods and opinions. There was no division in selection, many photographers submitted work to both journals despite their allegiance to a particular school.

Another area of photographic practice that was being expanded at the time was the application of photography, particularly in colour, to medical procedures. The results could be used as either a diagnostic aid or a step by step record of an operation as a teaching aid.

1947 also marked the sesquicentenary of Lieutenant Shortland’s investigation of Port Hunter in September 1797. His discovery of coal is recognised as the most important reason for Newcastle’s foundation. Among the celebrations mounted by the City of Newcastle was a Salon of Australasian photographers. Oswald Ziegler had already produced commemorative souvenirs for the city when he used the Salon as the basis for Australian Photography 1947.

The selection of professional works was handled by Oswald L. Ziegler, Hal. Missingham and S. Woodward-Smith and the amateur works were selected by the commercial moderns Max Dupain, Athol Shmith and Russell Roberts. The prizes were judged by S. Woodward-Smith and awarded by Newcastle’s (Lord) Mayor H. D. Quinlan. In all, seventy-one photographers and studios were represented.

The Pictorialists, the aging masters, had adapted to the sharper quality of modern lenses and emulsions in their approach to landscape photography. Their work was not as painterly as it had been in their heyday. A strong branch of the school had turned away from general landscape to studies of individual trees, particularly eucalypts. As several more modern photographers were also interested in individual trees as part of the modern aesthetic of individual studies, those Pictorialists who followed this trend were able to gain more respect than those still following their nineteen-twenties style. Ure Smith published Australian Treescapes as part of the company’s Miniature Series about this time.9

The more standard images of the Pictorialists included in Australian Photography 1947 feature such classics as Harold Cazneaux’s Sydney Harbour images and Julian Smith’s portraits. The graininess of classic Pictorialism is not so obvious although mist and fog appear as painterly devices in some images.

The Moderns submitted both commercial and freelance work. Industrial and fashion photography are the predominant commercial works. By far the most outspoken of the modern school is Max Dupain. His article, ‘Factual Photography,’ at the start of Australian Photography 1947, is a manifesto condemning the cringe that Pictorialists had committed by hiding their photography under imitative painterly techniques. There is very little architectural work, most of which is European. Only Margaret Michaelis and Athol Shmith portray modern architecture.

There are a few nature studies, nudes and portraits of the notable. Medical photography and microphotography appear as items of technical interest. There is little technical interference in the printing of the photographs. Athol Shmith’s portrait of the cinematographer Alec. Cann is the only obvious use of montage and contact printing. The colour photography section exhibits a curiosity about colour film. Only a few images, mostly fashion illustrations, use colour in a creative way.

The layout of Australian Photography 1947 is simple, with each photograph taking up a single page (with a few exceptions). The opening essays, headed in brown, are set out allowing for their varying lengths. Gert Sellheim designed the book with a classic formality not unlike the illustrated sections of contemporary photographic journals. The medallion design, adapted later for Australian Photography 1957 was by Lyndon Dadswell.

|

# 3: One version of the Australian Photography 1947 dust jacket,

showing the photograph Australian Dimension by Paul Horne. Another version shows an Axel Poignant image.

|

| |

|

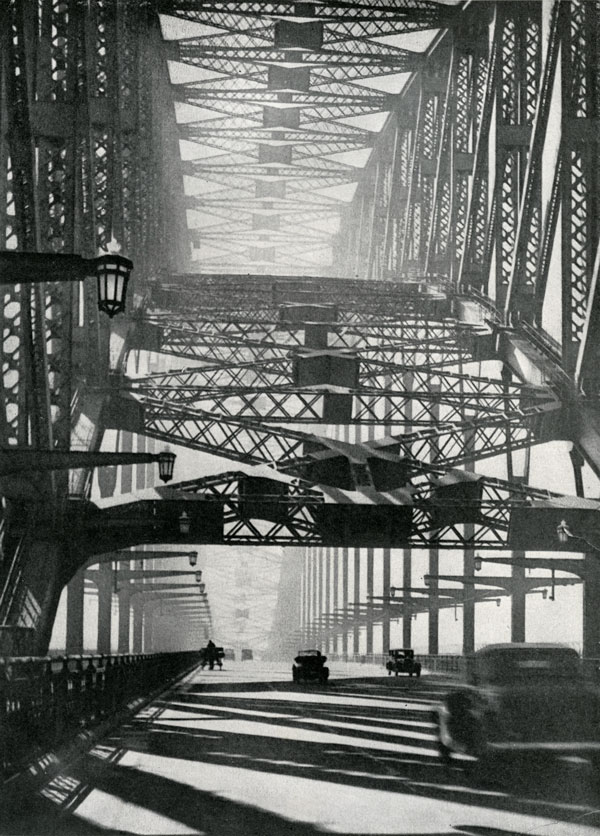

#4: Examples of Pictorialist work, Arch of Steel by Harold Cazneaux above,

Forest Fantasy by V. S. Gadsby below. both printed in Australian Photography 1947. |

|

| |

|

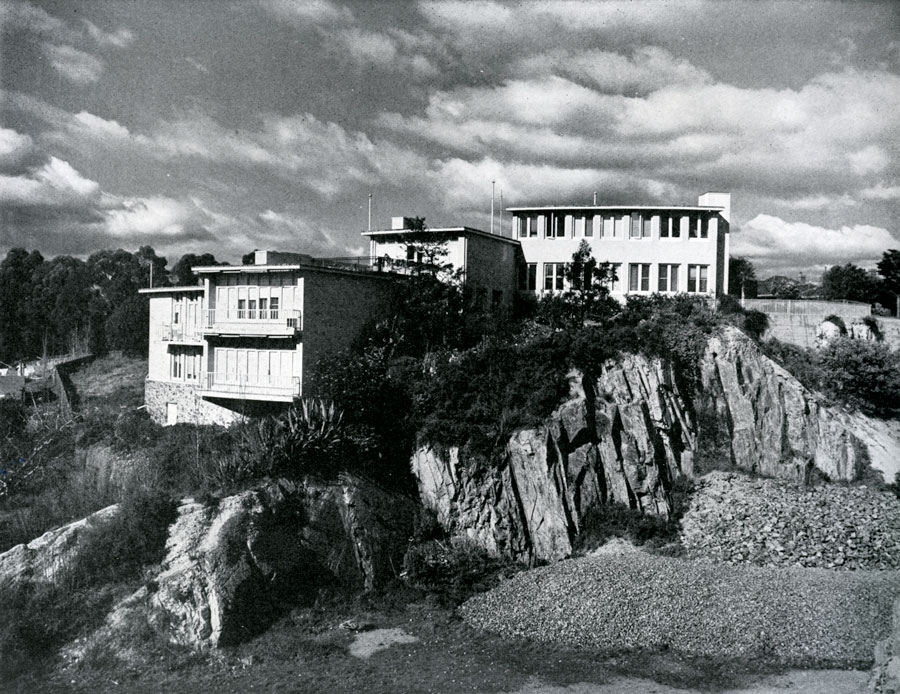

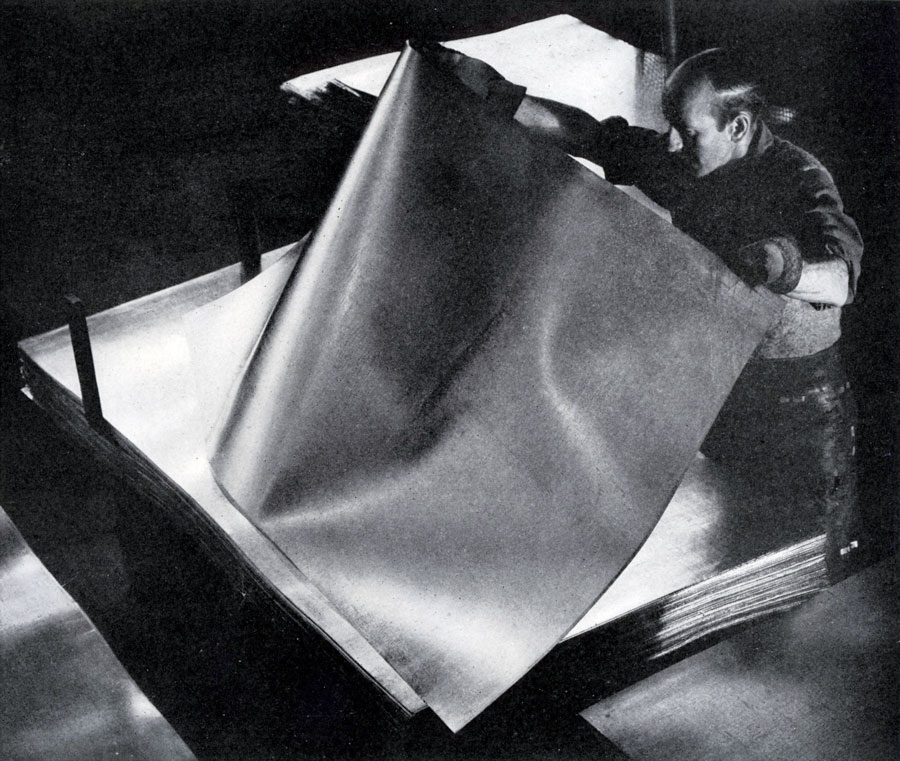

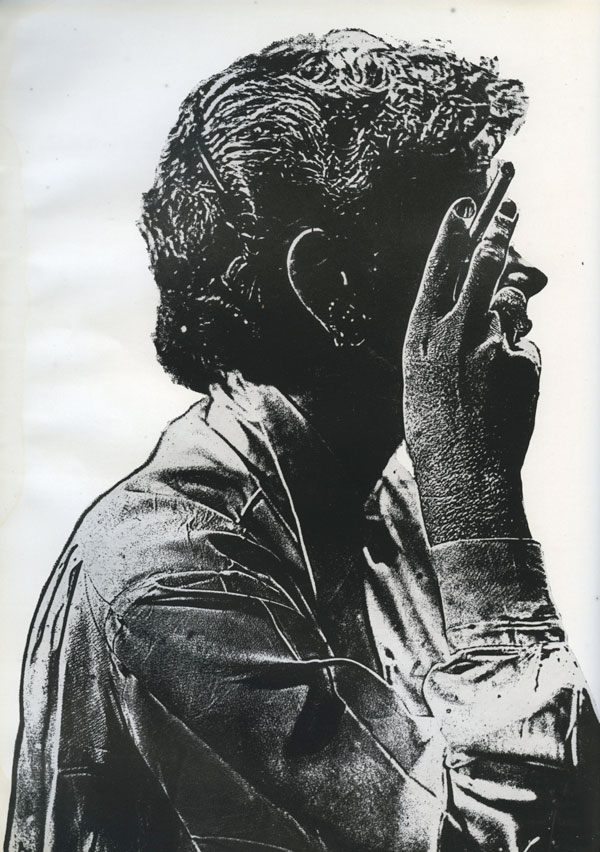

#5: Examples of the Modern Commercial School. Athol Shmith’s Architectural Design is above,

Russell Roberts’ Sheet Metal, Lysaghts, Newcastle is below. Both printed in Australian Photography 1947 |

|

| |

|

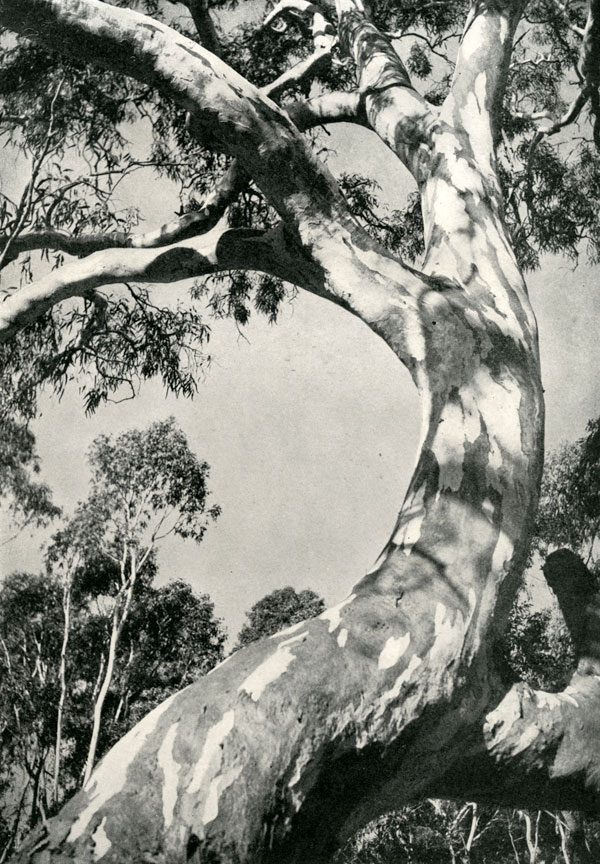

#6: Modern Portraiture, Russell Roberts’ Mavis Ripper above.

Below is an example of the interest in tree photography, The Curved Gum by Harold Cazneaux. Both printed in Australian Photography 1947 |

|

By 1957 the post-war austerity period was long over and there were no longer restrictions on photographic materials. Expanded pictorial content in Australian magazines and their imported equivalents influenced a new generation of photo-journalists. The Family of Man exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in the early fifties and the subsequent tour and distribution of the catalogue had established photo-journalism as a major cultural phenomenon of the time.

Laurence Le Guay and David Moore, with one image each, were local photographers involved. Moore’s Redfern Interior of the late forties is the only Australian image along with Le Guay's Papua New Guinea photograph (then an Australian Territory). Margaret Michaelis-Sachs was another local Family of Man photographer, albeit with a work which antedated her arrival in Australia. She’d already appeared in Australian Photography 1947.

After a wartime decline the fashion magazine returned. Vogue Australia was launched in late 1959, among the pioneers of the overseas name in local production. Photographic imagery in Australia was greatly influenced by the arrival of television in late 1956.

These changes were influential in the production of Australian Photography 1957. The layout of Australian Photography 1957 was based on the Family of Man catalogue.10 Photo-journalism and fashion photography are well represented in the selection. There is a tendency towards very sharp, highly contrasted printing in those genres. The cover of the book, designed by Strom Gould using an image by Athol Shmith, resembles a series of super-imposed television screens.

By now the surviving Pictorialists were aging and A.P-R had folded the previous year, outliving Contemporary Photography by over five years. Landscape was now largely superseded by human interest subjects. Those landscapes which appear in Australian Photography 1957, despite being well composed, fail to compete with the dynamism of the human images. Nudes within the landscape, a practice of the modern school in 1947, are given more space in Australian Photography 1957. This possibly echoes the return to more naturalistic backgrounds in contemporary painting after the Classicism associated with Australian nude painting since the 1890s. John Brack’s nudes in suburban Melbourne were among the first in this trend.11

There are more solarisations, higher contrasts, montages and experimental print surfaces. The colour section, now central rather than relegated to the back, exhibits a more studied approach to colour aesthetics. In the selection of colour images, as with the monochrome, a preference towards the commercial is more evident than in 1947. Because colour in magazines was no longer a novelty, there was a greater need for a sustaining interest in the image, not just the prettiness of the subject’s colour. The chaotic colours and simple compositions of 1947 are abandoned in favour of deliberate highlighting and subduing of the colours among carefully contemplated poses and arrangements.

Because of the expansion of the local photographic industry, less imagery from overseas journeys or residences appear in 1957 than in the 1947 edition. David Potts’s images of Europe are among the exceptions; even so they are human interest photo-journalism subjects which fit the overall content of Australian Photography 1957. Scientific (technical and medical) photography is absent from the selection. Architectural work is poorly represented despite the expanded pictorial content of architecture journals like the then recently retitled Architecture in Australia.

The majority of the architectural images are of industrial subjects. Ironically, the industrial images of 1947 hold more human interest compared to 1957’s offerings. Milton Kent & Sons’ Hospital Façade is a good example of architectural photography but the subject, Sydney’s King George V Memorial Hospital, was over a decade old. The lack of contemporaneity is disappointing considering the importance of 1957 in the new curtain wall style, e.g. the completion of the Qantas Building in Sydney.

In his foreword to Australian Photography 1947, Hal Missingham criticised the lack of beach, sport and city images. Laurence Le Guay, in his Australian Photography 1957 article ‘The Modern Trend in Photography’, wrote of the increase in human interest subjects buy lamented the concentration on the poor and depressed side of life. Australian Photography 1957 does not feature much in the way of these poverty-inspired images buy Le Guay’s criticism of landscapes and character studies is to no avail.

The essays at the start of Australian Photography 1947 are more technical and larger in number than those of Australian Photography 1957. Both sets of essays reflect their time. In 1947 the industry was experimenting with new technology introduced into civilian practice. By 1957 the chief interest of the essays is the aesthetic merit of the selected photographs over those rejected by the production team and the everyday snapshot.

While the mixture of amateur, artistic and commercial photography may seem uncomfortable to today’s methods of photographic exhibition, it should be remembered that the amateur and commercial photographers were the backbone of photographic Salons to a greater extent than their modern counterparts.

Art Galleries dealing in photographic work would not consider the mid-century approach to Salons and anthologies as a basis for an exhibition. Amateur and Society shows are largely ignored by photographic criticism. Annuals devoted to Australian Photography could no longer follow Ziegler’s pattern. In an industry often all too caught up in constant updating, the methods of thirty to forty years ago seem dated but the Australian Photography annuals to come from Oswald Ziegler Publications occupy a place in Australia’s photographic history.

|

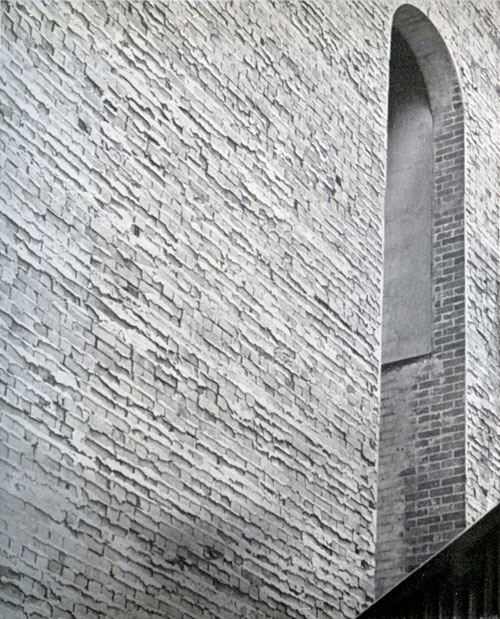

#7: Above and below, examples of the high contrast work of Australian Photography 1957.

above: J.Archer, untitled; below C. R. Bennett Wall Texture; Athol Shmith, untitled portrait |

|

|

| |

| |

|

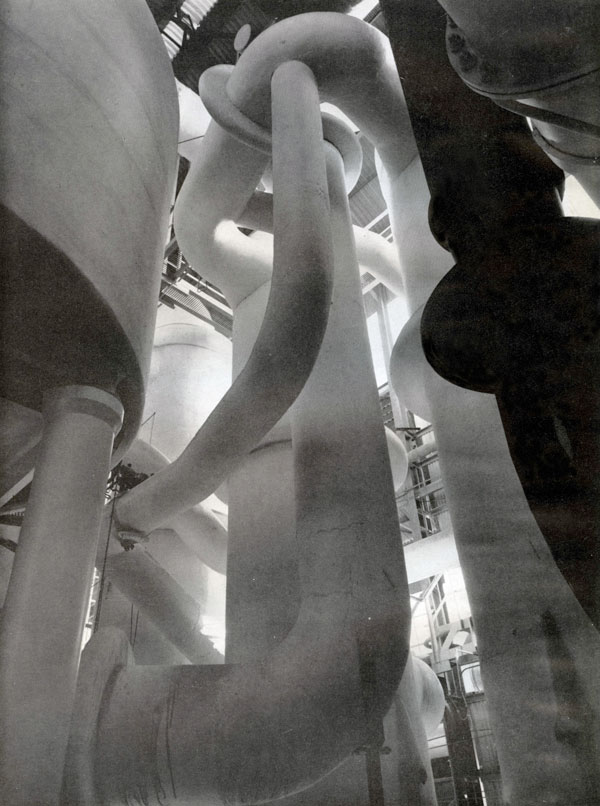

#8: Industrial Photography from Australian Photography 1957.

Above: Muriel Jackson, Pipeline for Peace; Below Wolfgang Sievers, Electrolytic Zinc, Hobart |

|

| |

|

|

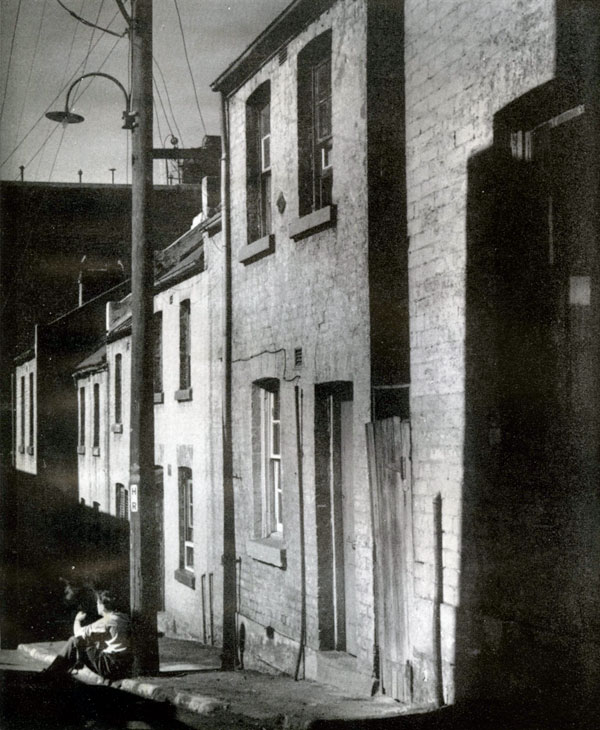

#9: Urban images from Australian Photography 1957, showing the influence of The Family of Man which sought to represent as much of human society as possible.

Top above: Kevin Aston, Little Burton Street; above - Ivan Morley, Back Street. Below Henry Talbot, Woolloomooloo 1956 |

|

Notes:

- Jean-Marc le Pechoux, Peter Beilby, Australian Photography Yearbook, Melbourne 1983.

- Anne-Marie Willis, Commercial Photographers, Artists and Hippie Photofile Volume 1, Number 3, Spring 1983, pp 8-9.

- Published by Harringtons in 1984 and 1986. Laurence Le Guay, Photography in Ziegler Commonwealth of Australia Jubilee 1901-1951,

Sydney, 1950, p 61.

- Advertised on the back cover of Portrait of Sydney, Sydney, c. 1950.

- Published by the Museum of Modern Art and MACO, New York, 1955.

- There were many paintings of nudes in the landscape from the aborigines of the 1790s onwards

but Brack is a popular example of the less pretentious fifties style.