|

|

Home-Page / Introduction / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / Conclusion / List of Images / Bibliography

Chapter TwoThe Road in Australia Photography with a focus on The Road by Wesley Stacey

In the introduction to The Penguin Book of the Road, editor Delia Falconer observed the absence of the road in Australian culture: Roads, in Australia, have never been the 'glossy black dance floors' of Nabokov's America. We have produced no home-grown Whitman or Kerouac to sing the freedom of the open road or riff on the exhilarations of the highway...Our road stories may not subscribe to the triumphalist grandeur or existential wildness of the American tradition, or share its generic self-awareness (they are often part of other stories rather than 'road stories' perse)...137 The scarcity of Australian road literature of the status of Kerouac's classic On the Road is repeated throughout the Australian cultural landscape. The road The openheartedness with which America grasped the road and elevated it as a generally positive and optimistic symbol of freedom has not had the same reaction in Australia. Instead there has been a hesitancy to fully embrace the road. The resistance to exploring the artistic potential of the road in the arts also extends to photography. The theme of the road in Australian photography has not had as significant presence as in America. Few photographers have embarked on a photographic road trip in the vein of the FSA photographers, or with a specific intention of providing "a visual study of civilisation"140 as Robert Frank did. Axel Poignant (1906-86) travelled around Australia, including a camel expedition along the Canning stock route in the 1940s, which could be considered within the same context as the FSA photographic trips.141

But Poignant favoured portraits and the 'photo-story'142 rather than deliberately embarking on a photographic road trip. Russell Drysdale (1912-81) experimented with photography and took images of the road yet there was no purposeful vision involved. He was interested in the theme of architecture vernacular as well long perspectives down main street (Fig. 29) and found photography to be an "informal, intuitive way of focusing on the material of his daily life."143 It was not until the 1970s that there was a deliberate and sustained photographic road project - Wesley Stacey's The Road (1973-75).144 In this chapter The Road will be examined in relation to the tradition of American road photography to discern if there are any similarities and show how the road in Australian photography differs from the road in American photography. It will be argued that in The Road there is a greater focus on the road in and of itself, a marked distinction from American road photography. Stacey's desire to express the 'driving experience' will be considered along with the differing relationship to the land and the alternate meanings asserted through framing choices. The use of the road as a motif will also be examined in relation to work by Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank before considering aspects of 1970s Conceptual Art present in Stacey's series. During 1973-75 Wesley Stacey (b.1941) embarked on a road trip around Australia resulting in a series of 280 colour photographs capturing his view from his Kombi van entitled The Road. The series is divided into 17 folios, each with a specific focus and linear sequence: The Outback to the City, Work Day Roads, Peak Hour Roads - Sydney, Lots of Cars, Roads to the Red Brick Home, Weekend Roads, Sydney to Canberra, Marangaroo to the Nullarbor, Kalgoorlie to Port Headland, Port Headland/Witternoon/Roeburn - WA, Paraburdoo and Tom Price - The Pilbara, Suburbs on the Sand, Perth Fun City, Up Tha Centre, Gulf to Burdekin, Surfers to Hobart, and Night Roads. Using the new technology of a Kodak Instamatic camera, its small size and easy focus enabled him to work quickly and intuitively. The Road was exhibited at the then recently established Australian Centre for Photography (ACP) in Sydney in 1975. The series was a significant departure from the conventions of art photography of the time which was still grounded in formally composed, black and white images. The series was well-received by diverse photography cognoscenti Gael Newton and David Moore, both agreeing it was a landmark work despite differing tastes, and influential curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, John Szarkowski, declared it "the most radical he had seen in Australia."145

The Australian Road and the 'Driving Experience'On the surface, Stacey's The Road appears to be very similar to Stephen Shore's American Surfaces. Both set out across their respective countries photographing their journey in a 'snapshot' style. Both were engaging with the new technology of the time, the Kodak Instamatic, and both commercially processed their colour film and prints. In doing so the two photographers were straying from the established art photography conventions of black and white formally composed images with great concern with printing style.146 Yet the two resulting series have striking differences. Shore's intention was to document a visual diary of his road trip and as such it is personal, intimate and inclusive. Shore leaves his vehicle and takes his camera into the motels, diners, and restaurants he frequents, he takes portraits as well as the view from his car. Stacey, on the other hand, desired to capture the "driving experience"147 of travelling in Australia. His images are shot from the vehicle and Stacey reacted to what appeared through the windscreen.148 Stacey's series is therefore limited to the view from the car and demonstrates a very singular vision. The majority of the images in The Road are devoid of people149 and this speaks of the importance of landscape in the series. Judy Annear contends that Stacey belonged to a group of photographers who desired to "re-present the landscape in all its wild untidiness rather than through the grid of a European landscape tradition which demanded a structure and presentation completely foreign to this country."150

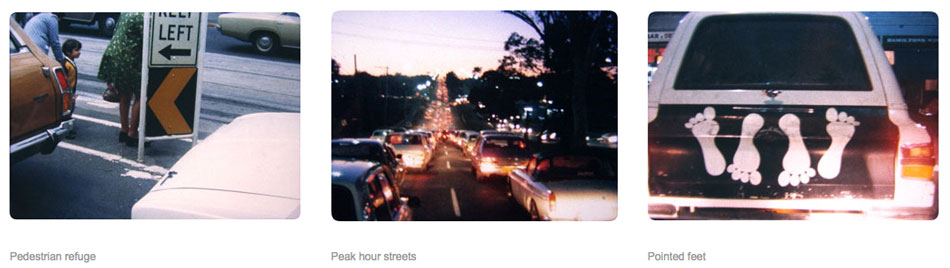

If it appears that Stacey is favouring the environment above people it is because he does not consider himself a photojoumalist nor a portraitist and he asserts that he just shot what appeared through the windscreen, "people or no people."151 Yet his imagery shows a greater concern for the landscape rather than an attempt to capture society which defines much of the American road photography. Few photographs feature people as individuals (Fig. 30), by and large they figure as just one component of the general scene (Fig. 31). The relationship photographers had to the land in America was not the same as in Australia. Helen Ennis argues that photography went hand in hand with the opening up of the American frontier whereas in Australia it did not.152 Indeed many photographers willingly went west to photograph the new landscape opening beyond the Mississippi and Missouri after the American Civil War.153 Ennis' view is supported by the fact than during the first fifty years of photography in Australia not a single expedition was photographed; explorers confined their record making to maps, journals and sketches.154

The resistance to capturing the reality of the landscape could have been an attempt to deny its harsh, alien and forbidding physical aspects.155 In other art forms such as painting artistic license permits a greening and softening of the landscape, as seen in the work of Conrad Martens for example (Fig. 32), where the finished work was intended to promote the civilisation of the country. Decades later the "picture postcard" tendencies in landscape photography were to be superseded by those such as Stacey who focused on the nuances rather than the "grandeur of the continent156 Stacey gleefully embraces the Australian landscape, literally throwing himself head first into it, albeit mediated by the camera and windscreen.

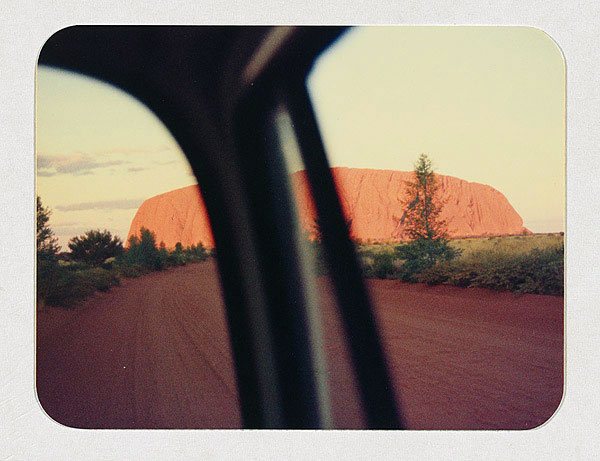

By virtue of photographing through the windscreen, Stacey's images are noticeably framed. This device is a constant reminder that these images are taken whilst travelling the road and reinforces that the essence of this photographic road trip is the road. Stacey's image of Uluru bisected by the window frame (Fig. 33) is far removed from the usual picture-postcard aspect. The severity of the bisection reflects the split between the spiritual and the tourism facets of the ancient monolith. Shore's images rarely highlight the fact that he is travelling by car yet he too also frames his shots in a way that assert specific meaning. Regarding U.S. 89 Arizona, June 1972 (Fig. 34), Shore

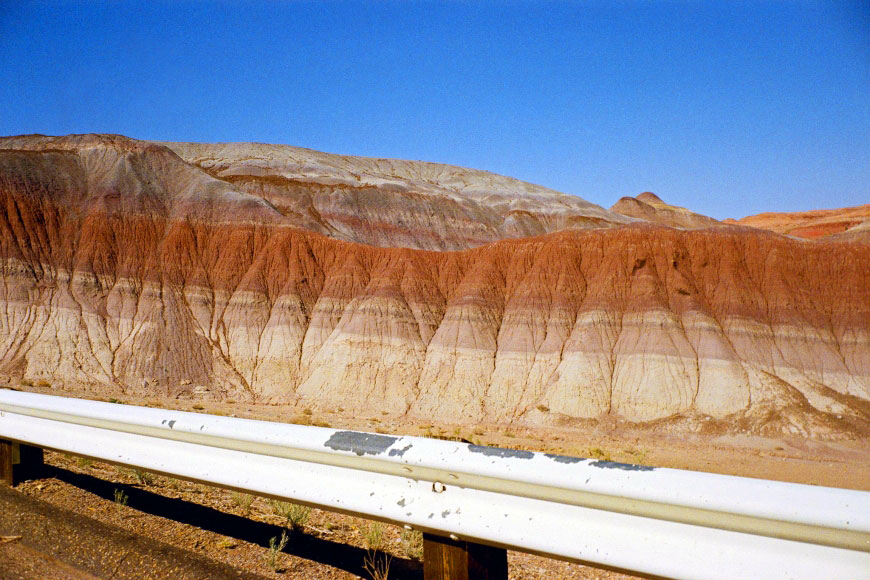

The inclusion of the guardrail and fragment of asphalt acts as signpost of not just man's intrusion on the natural landscape but similarly to Stacey's use of elements of the car within the composition, contextualises the image within the photographic road trip genre. The 'view from the car' aesthetic promoted by Stacey in his series has more recent parallels to American road photography. A compendium of Lee Friedlander photographs taken over the last ten years were published and exhibited this year entitled America by Car.158 Every one of the 192 images contains elements of the vehicle within the composition creating interesting juxtapositions between the interior of the vehicle and the exterior world of the American highways, cities, suburbia and landscapes.

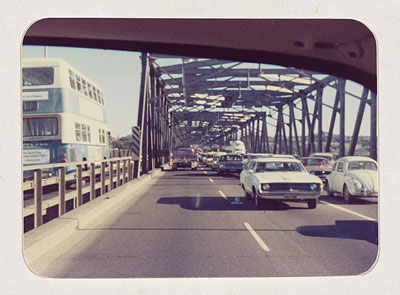

However the "sensory overload commonly experienced by American drivers159 that Friedlander wanted to express is not necessarily shared with Stacey's photographs. Friedlander's images are crowded compositions whether by landscape (Fig. 35) or signage reminiscent of Evans and Frank (Fig. 36) whereas Stacey divides his camera between the crowded and the spare. An image from the Perth Fun City folio (Fig. 31) captures a busy street scene with lanes of cars and an imposing billboard and advertising signage sandwiching a stream of pedestrians. On the other hand his image of the Gladesville Bridge (Fig. 37) from the Weekend Roads folio, with seven cars and one motorbike over six lanes, is a calming respite from the normally traffic-laden road.

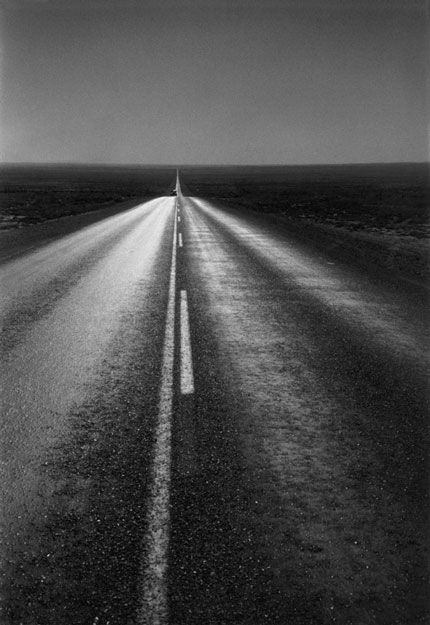

Evoking the Spirit of the RoadThe repeated image of the road itself in Stacey's series denotes a major point of difference from the traditional American road photography: the road as a motif in and of itself. The very title of the series, The Road, states the focus clearly and the first folio, Outback to the City, encompasses a variety of roads throughout Australia. There are straight orange dirt roads, sandy roads edged by saltbush, winding roads through the bush, paved roads in the country, urban roads, highways, roads through tunnels and a suburban street with a floral median strip.160 Beginning with such a defined subject matter positions the series unequivocally within the road genre and this statement is reasserted throughout the rest of the series and these pictures attempt to evoke "the spirit of the road.161 Traditional American road photographers on the other hand, tended to not train their lenses on the road itself in their search for America, instead focusing on the people, buildings and other images of the vernacular. Despite the emphasis on the view beside the road in American road photography, there are notable exceptions.

Whilst Dorothea Lange's focus was largely directed at the migrant workers, the road itself did feature as an individualised entity. One of her most striking FSA road images is The Road West (1938) (Fig. 38). This image, photographed on a stretch of U.S. 54 in Southern Mexico, is empty and endless, yet with the possibility of optimism. Many families who hoped to find work in California took the west-bound route along this highway. Unfortunately, once in California they often discovered conditions no better than those they left behind, and frequently returned from whence they came.162 The emptiness of this road can also symbolise the potential futility of the destination ahead. This road may lead to nothing for many of the travellers upon it. However accompanying this image in An American Exodus,163 the book published by Lange and her husband Paul Schuster Taylor in 1939, is a comment from a person met during the trip. "They keep the road hot a goin' and a comin'...They've got roamin' in their head,"164 which is suggestive of the hordes of folk that must have traipsed along this road, transforming it from an 'empty' road to a road haunted by many. Automobiles and the act of driving and car culture feature strongly in Robert Frank's The Americans and one image in particular places the road on centre stage. Frank's U.S. 285 (Fig. 39) depicts a long stretch of highway disappearing into the horizon, empty, bar a single vehicle. The line markings, just off-centre, pull the eye far into the distance. The visual similarity to Lange's The Road West is undeniable yet the meanings of the road images differ. Lange's road contained elements of hope, that in the distance a new life may be possible. Frank's road is more ambiguous. Walker Evans remarked that "in this picture, instantly you find the continent...the whole page is haunted with American scale and space, which the mind fills automatically."165 Kerouac saw the whole of The Americans as a journey and described U.S. 285 as "long shot night road arrowing forlorn into immensities and flat of impossible-to-believe America in New Mexico under the prisoner's moon."166 Jno Cook poses that as the photograph was taken at night, the image is about the stars (in the sky) and stripes (on the road) and thus is a personification of the American flag,167 a recurring motif in The Americans. Yet Cook also argues that there is nothing symbolic or metaphorical about the image. Instead, with a car approaching on the correct side of the road, it demonstrates a single aspect of the American character - the obedient citizen, one who does not cross the solid line.168 However, the blankness of Frank's road, the only image of the road as a singular motif within The Americans, can be seen to invite individual, personal projections. Here, Frank's road can be read as a metaphor for what the New World represents: a place where you can make yourself what you will. While Lange and Frank sparingly feature the road and in doing so make a strong and evocative statement, Stacey's repeated imagery of the road invites a different interpretation. According to Stacey the act of photographing from the driver's seat was "a new way of getting out and about photographing in Australia in a way that hadn't been done before." The sensation of being in a Kombi van was intoxicating, a visual revolution occurred - the equivalent to the nineteenth century phenomenon of train travel - sitting up high with the view speeding past.169 Stacey wanted to emphasise that "there's more than one way to go - across the Bridge, the Nullarbor, the Centre."170 So the plethora of roads represents choices and alternative paths and the contradictory distinctiveness yet sameness of each. In The Road, each road is different and travelling along each one results in a different experience but all lead to the same horizon. For Stacey the 'driving experience' was a way to celebrate the "variousness of Australia - numerous and haunting."171 The series encompasses four divisions of Australia - urban, suburban, the coast, and the outback or bush - and within these categories the strange and the common are visible, with the strange evoking wonder and the common nostalgia.

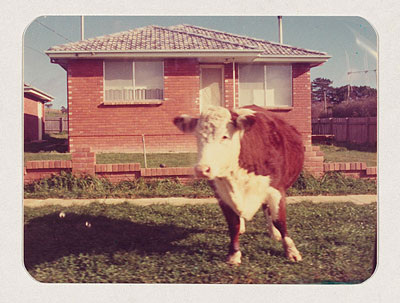

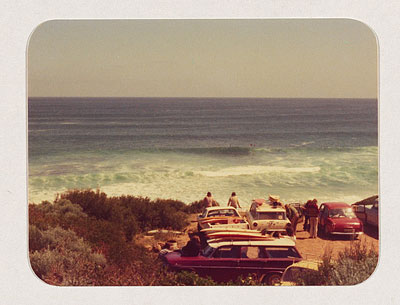

A Volkswagen Beetle parked outside an office block in North Sydney (Fig. 40) brings the 1970s to life as does an icon of the era, a brown vinyl beanbag (Fig. 41) incongruously stuffed into the boot of a car. The ubiquitous suburban red brick home is given a surreal twist with the presence of a cow on the verge (Fig. 42) and two boys on their (now retro-cool) bikes, dressed in purple and eating lollies (Fig. 43), triggers nostalgia for the time when cycling without helmets was the norm. Surfing culture is also present and archetypal with parked cars laden with surfboards and surfers surveying the break (Fig. 44). One of the most haunting images is of a dead and wasted emu (Fig. 45). Its emaciated carcass and decimated feathers dissolving into the sandy floor gives an almost ghostlike appearance, half present and half fading away. The experience of driving along the roads of Australia expressed in these images is aided by the linear sequence in which they are displayed.

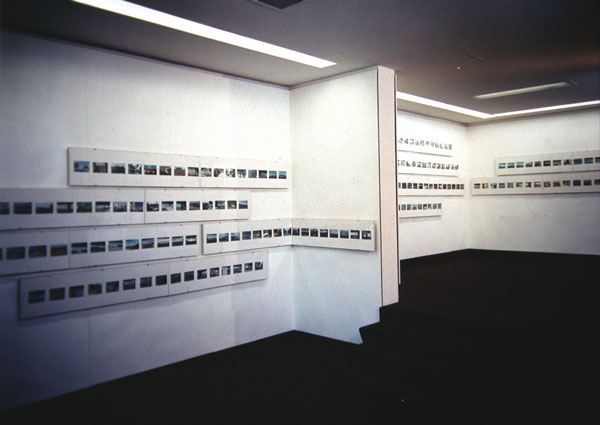

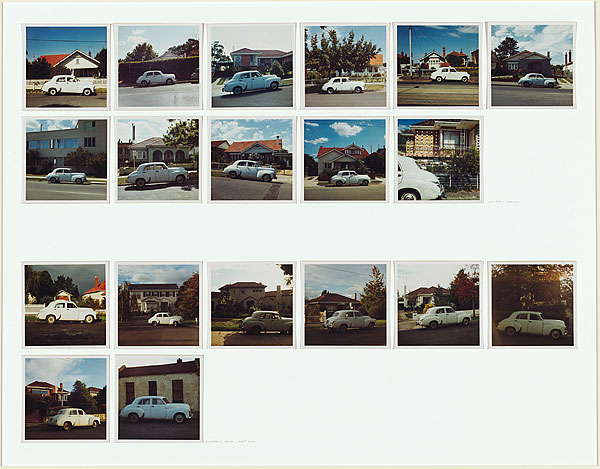

'Two Hundred and Eighty Roads': Stacey's The Road and Conceptual ArtThe sequential and multiple nature of the series The Road, rather than a continual trajectory that mirrors the journey, is another point of difference between Stacey's road photography and that of the American photographic road trip as captured by Frank and Shore. When exhibited in 1975 at the ACP, The Road was displayed in deliberate linear sequences (Fig. 46). Harry Williamson remembers the theme set Stacey's exhibition apart - most exhibitions were orchestrated around a sort of folio view of the photographer's range - interesting portraits, the city, the country and so on. But here was a close in, specific point of view sustained over many, many images.172 Stacey has had a continued interest in sequencing173 and the division of this series into folios is testament to his ideology. Some of the sequences are chronological, such as Across the Nullarboror Up Tha Centre, but other sequences like Peak Hour Roads and Night Roads are not, instead they feature multiple images of the same theme. In this sense, The Road can be seen as being closer to the tradition of Ruscha and Conceptualism. Ruscha's experimentation with road photography resulted in his serial works Twentysix Gasoline Stations and Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Whilst these works were at the very beginning of the Conceptual movement, they adhere to the philosophy that "the idea of the concept is the most important aspect of the work...and the execution is a perfunctory affair."174 Ruscha was driven by an idea and he realised it faithfully and single-mindedly with his series of eponymous gasoline stations and every single building on the Sunset Strip. Lucy Lippard's assertion that "the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious and/or dematerialized"175 is also evident in the way that Ruscha produced his books. He was interested in the democratic notion of making a cheap, mass-produced object for broad dissemination stating "I wanted to get the price down, so everyone can afford one. I want to be the Henry Ford of book making."176 Comparisons can be made with the single-mindedness of Ruscha's approach and execution with that of Stacey and The Road. Stacey was aware of the American road photographers and says they "did take a lot of road pics, lots of them arty" whereas he was focused on "a grand theme."177 This grand theme, or concept, was the road and the disregard of aesthetic formal qualities of his photography when achieving his grand theme is a marker of Conceptual Art. The choice of using the decidedly non-elite Kodak Instamatic and commercial processing also speaks to the Conceptual concern for art made from cheap or transient materials.178 The folio Outback to the City contains images the most concomitant with the work of Ruscha. Seventeen different roads photographed from the same viewpoint, the driver's seat, each with the tell-tale framing of the windscreen. The images are repetitive yet compelling in their ordinariness. The similarity to Ruscha's Twentysix Gasoline Stations is apparent; the folio could easily be renamed Seventeen Roads (or the entire series Two Hundred and Eighty Roads) and still remain true to Stacey's desire to express the driving experience as well as evoking the spirit of the road. The serial nature of The Road has a precedent in Australian photography. The work of Melbourne artist Robert Rooney (b.1937) develops out of the Pop art aesthetic and relates to his urban and suburban environment often engaging with Conceptual seriality.179 His Holden Park 1&2 1970 (Fig. 47) depicts 19 polaroid images of a Holden car parked outside various dwellings. The work is displayed in a grid pattern that is not quite complete. The uneven layout is suggestive of lines in a paragraph and invites the viewer to scan the lines as if reading a text (Rooney spent many years working in bookshops).180 Jennifer Phipps revealed a commonality with Ruscha in "the immersion in deadpan visual and verbal puns"181 which is revealed in The Road as well. Stacey also engaged with puns naming one of the folios, Lots of cars.

The folio contains many images of cars but the images are also of car lots, mainly along Parramatta Road in Sydney with large prices plastered across windscreens and colourful plastic bunting strung across the sale yards (Fig. 48). Stacey may or may not have been familiar with Rooney's photography but the common interest in seriality and sequencing in conjunction with the automobile connects the two. The 'driving experience' as expressed by Stacey is a major point of difference between his road photography and that of traditional road photography in America. Stacey's peer, fellow photographer Philip Quirk stated that "many photographers...used the road as a means to arrive at a predetermined subject...Wes made the whole journey his subject."182 The intention of the FSA photographers was to bring attention to the plight of the dustbowl farmers, Frank desired to depict aspects of American society, Ruscha was experimenting with typology and conceptualism - for all the road was a tool to achieve these aims. For Stacey the road itself was the aim and intention of his photographic road trip and is what makes his road photography distinctive.

>>>>> next: Chapter Three Home-Page / Introduction / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / Conclusion / List of Images / Bibliography If there are amendments or corrections you wish to suggest - please make contact.

|

• photo-web • photography • australia • asia pacific • landscape • heritage •

• exhibitions • news • portraiture • biographies • urban • city • views • articles • • portfolios • history •

• contemporary • links • research • international • art • Paul Costigan • Gael Newton •