|

|

Home-Page / Introduction / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / Conclusion / List of Images / Bibliography

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

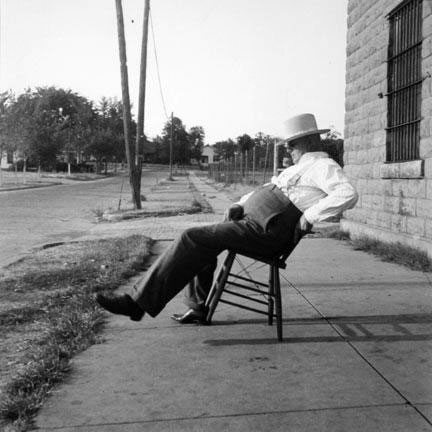

Fig 04: Dorothea Lange, The Sheriff of McAlester, Oklahoma, in front of the jail 1936, gelatin silver print, 17.3 x 24cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

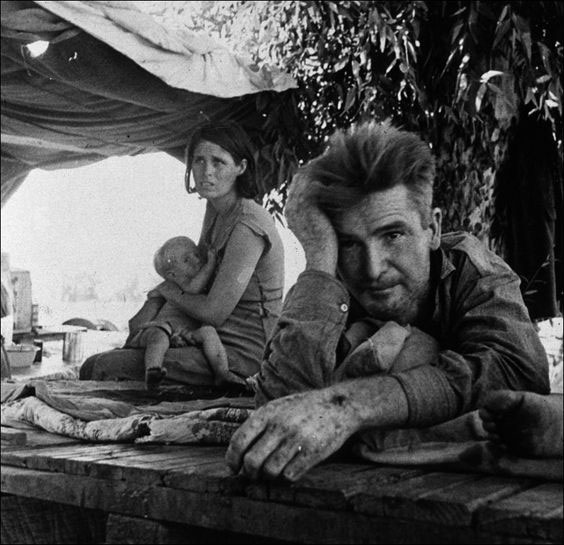

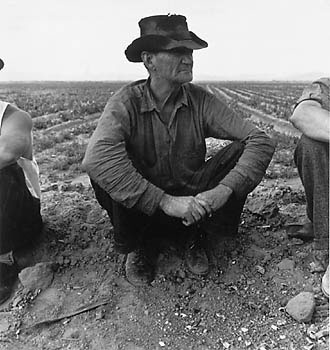

Lange's direct and honest photographic style effectively delivered the message that needed to be brought to the attention of the country.54 The images of drought refugee camps (Fig. 1) are heartbreaking, with despair etched across faces and the agony of idleness palpable, a sentiment also apparent in images such as Jobless on Edge of Pea Field, Imperial Valley, California (Fig. 2).

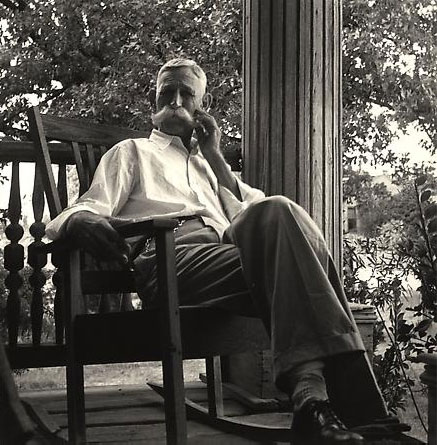

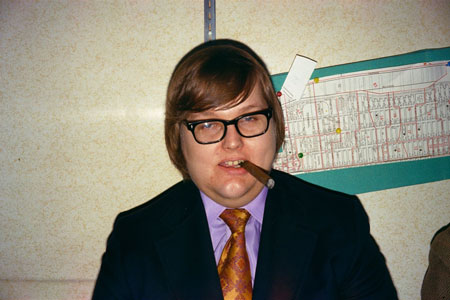

Perhaps even more so when contrasted with the still solvent such as the elder statesman of Greenville, Mississippi (Fig. 3) and The Sheriff of McAlester, Oklahoma, in front of the jail (Fig. 4), similar in the casual way the well-fed and well-dressed men recline. Yet amongst the desperation Lange allows indomitable spirit to emerge. In Rural Rehabilitation Client, Tulare County, California (Fig. 5) the woman's smile engenders a lightness of moment that admits the possibility of optimism for the future.

The juxtaposition of the hopelessness mixed with hope and the destitute with the solvent encompasses the ups and downs of life on the road that was to be a repeated theme in road photography. Perhaps the most significant photographer of the FSA was Walker Evans. Selected images from FSA commissions along with other photographs Evans took between 1929-37 travelling from Massachusetts to Louisiana appeared in the 1938 exhibition55 and accompanying publication56 both titled American Photographs. Evans and this book in particular have been cited as major influences upon many photographers.57 With his road photography there is evidence of the documentary tradition but also an interest and concern with the everyday that was to become a stronger presence in American road photography. Whereas Dorothea Lange was motivated by a desire to publicise the plight of the migrant workers, Evans was not so altruistic. He saw an opportunity to travel the country and take photographs, to be an artist.58 Evans was able to achieve this despite the aim of the FSA photographers to capture images that would highlight and elucidate the predicament of the rural poor to the urban poor,59 primarily because away from editors, clients and bureaucrats, in the field Evans and the other photographers found themselves as liberty to make "true photographs."60 |

|

|

|

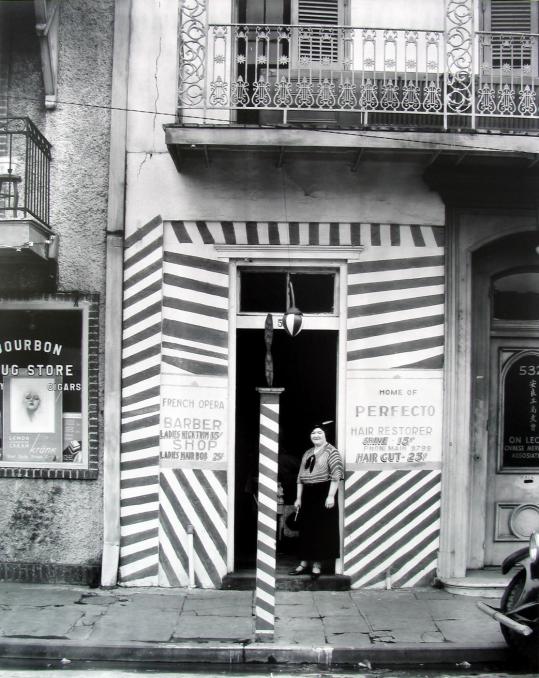

Evans believed the role of the photographer was to describe life, which often clashed with Stryker's expectation of the country being reformed through exposure to such images.61 It is the 'descriptions' of everyday life that Evans captured with his lens, such as Sidewalk and Shopfront, New Orleans (1935) (Fig. 6) which combines a 'portrait' of a woman framed by the diagonal stripes of a barber shop with the graphic signage that evolved into a recurring theme in road photography that will be expanded upon later in this chapter.

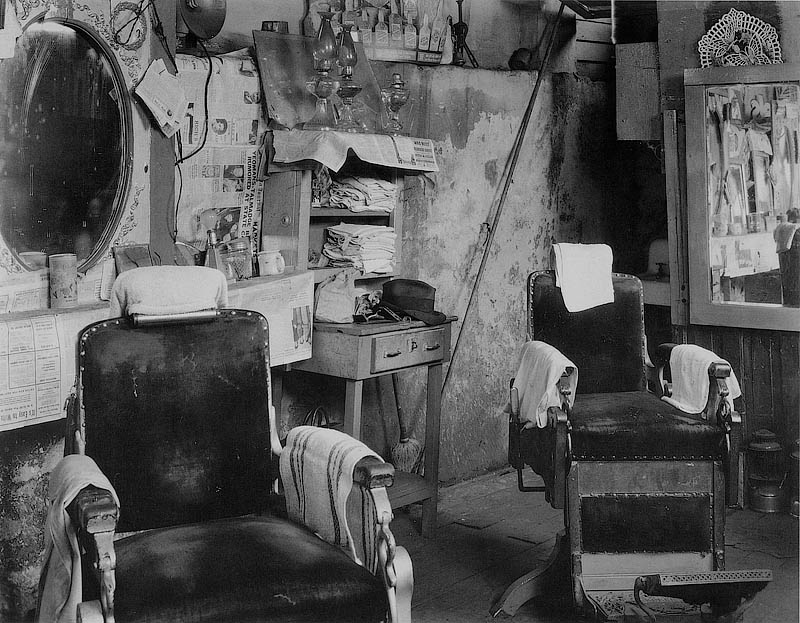

Laufer contends that Evans' theme would be "mythic America" and he would "utilise the myth of the American road as the means by which he would examine those beliefs in contrast to the cultural realities he discovered."62 Evans' images are a reflection that causes society to pause and consider. The shabby, cluttered, decrepit Negro Barbershop Interior, Atlanta (1936) (Fig. 7), contrasts sharply with the preceding much smarter barber shop with a white female customer. The placement of these images in the book was intended and is hard to ignore. As Alan Trachtenberg asserts, "...his is the mirroring eye through which we not only see but contemplate ourselves in the world we create and inhabit."63

|

|

|

|

Fig 07: Walker Evans, Negro Barbershop Interior, Atlanta 1936,18.9 x 23.2cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York |

This was a consequence of images taken from the road that would recur. The contrast between the myth and the reality would play out in later generations of road photographers, most significantly in the work of Robert Frank. Evans spent approximately two years travelling along the Atlantic Seaboard visiting cities and towns and his road photography revealed America. As photographer Carl Van Vechten commented, "If everything in American civilisation were destroyed except Walker Evans' photographs, they could tell us a good deal about American life."64

The experience of being on the road during the Depression was common concern within the arts. It was not only captured and expressed by photographic work, but also in literature and film. John Steinbeck's classic novel The Grapes of Wrath, which details the devastating effects poverty has on a family heading west for something better, had a very close connection with the FSA. Steinbeck wished to write a book about migrant labour and visited the FSA offices for research purposes. He spent several days with Roy Stryker who showed him the file of pictures taken by the FSA photographers.65

One particular image by Lange, of camp manager Tom Collins, became the model for the camp manager in Steinbeck's novel.66 Steinbeck also spent time in 'the field' with an FSA official whilst disguised as migrant workers.67 The novel received a sensational reception with vociferous criticism of factual inaccuracies to accusations of communistic propaganda and calls (and action) for banning and burning.68 As a consequence the book became a bestseller, with sale of 2500 per day one month after release69 suggesting this was a story that wanted to be heard.

Steinbeck's novel was made into a film the year after it was published and has been hailed as a predecessor of the road movie.70 The filmic version of The Grapes of Wrath contains elements of thematic road movie iconography that would become standard and which also correlates to road photography. The suggestion that road travel as a vehicle for revelation, a place for learning lessons, the site of hope and enlightenment as well as despair, are all symbolised in the roads in The Grapes of Wrath.71 Visual techniques such as reflections of faces in the windscreen and rearview mirrors, characters framed within frames of the vehicle, and the "point of view" shot when the camera is placed on the car, are techniques prominent in later road movies.72

What is evident is that the artistic output of road imagery and the experience of being on the road was a direct result of social and historical conditions. The farmers could no longer make a living on lands they had worked for years and so had taken to the road.73 The photographers, writers and filmmakers subsequently followed them. It was claimed that FSA photographs like Lange's, Steinbeck's novels and film did more for those "tragic nomads than all the politicians of the country."74

The FSA photographers had a long lasting and significant influence upon later generations of photographers. The idea of travelling across America and photographing people and places along the way that resulted in capturing and expressing a society was to be repeated. The combination of Lange's concern with the plight and experience of ordinary folk with Evans' eye for signage and emerging vernacular of the road would find resonance with the younger generation of photographers.

Evans in particular has been influential also in terms of his selection process and publication of his images. His book, American Photographs, became an inspiration for photographers like Robert Frank which can be seen in the similar layout of The Americans.75 Edward Ruscha also modelled the design of his book Twentysix Gasoline Stations76 after American Photographs as did Stephen Shore with American Surfaces.77 These photographers saw in Evans' eye for the vernacular and the unassuming photographed in his documentary style a "truer portrait of themselves and their culture"78 and it is these elements that gained purchase as road photography became further established.

The Road Explores Popular Culture

The attention that Walker Evans placed on the everyday within the American social and cultural landscape spawned a recurring motif within American road

photography: the American vernacular. Photography curator Peter Galassi defined the vernacular as denoting "the indigenous and the common rather than the exotic and sophisticated."79 In 1934 Evans outlined his future photographic road trip plans in an unfinished letter beginning:

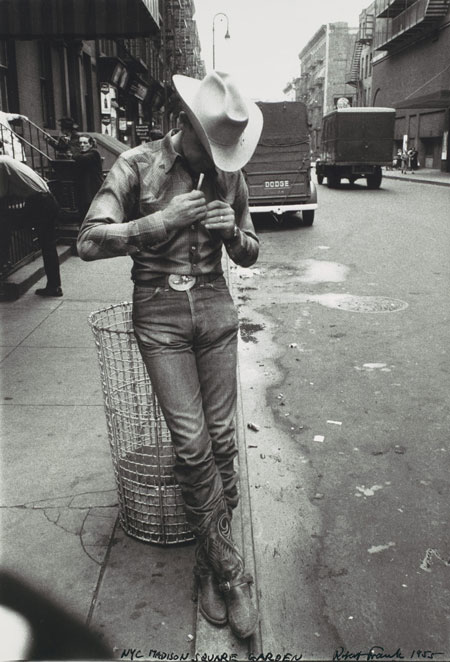

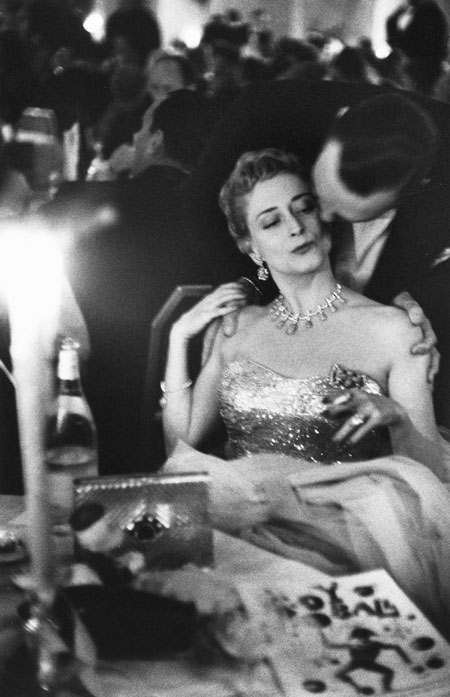

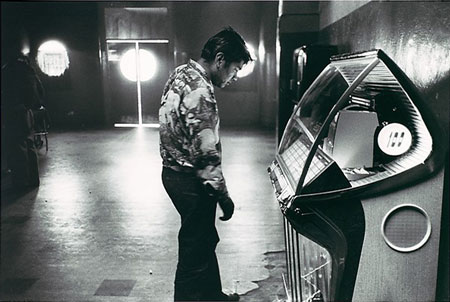

An American city is best...I know more about such a place...People, all classes, surrounded by bunches of the new down and out. Automobiles and the automobile landscape. Architecture, American urban taste, commerce, small scale, large scale, the city street atmosphere, the street smell, the hateful stuff, women's clubs, fake culture, bad education, religion in decay. The movies. Evidence of what the people of the city read, eat, see for amusement, do for relaxation and not get it. Sex. Advertising. A lot else, you see what I mean.80 Thus images of signs, shopfronts, automobiles, advertising billboards and gas stations increasingly became the subject of photographs taken on the road. Philip Gefter asserts that these common, everyday images still indicate signs of a course of discovery by a traveller, but instead of grand spectacles and intense events, they become "revelations about the ordinary."81 The 'ordinary' was also the common and the popular and so what was revealed in the next stage of photography from the road was American popular culture. A seminal photographic series from the 1950s that encapsulates the transition of the photographic road trip discovering America primarily through its people and the emergence of the American vernacular and popular culture is Robert Frank's The Americans. In his application for a Guggenheim Fellowship Frank articulated his intention to "photograph freely throughout the United States...l speak of the things that are there, anywhere and everywhere - easily found, not easily selected and interpreted."82 Frank travelled across America in 1955-56, photographing thousands of images of which eighty-three were selected for publication.83 Like Evans, Frank captured the network of services addressing the needs of the road traveller that America's love affair with the automobile produced: the motel, the billboard, the gas station, the payphone and so on (Fig. 8).84 Walker Evans' influence on the road photography of Frank was not just aesthetic but personal. It was Evans who encouraged the Swiss-born Frank to apply for a Guggenheim Fellowship, which he received and was the first foreign photographer to do so.85 This enabled him to go on his road trip. As an outsider, Frank observed America through different eyes. In the introduction to The Americans, Jack Kerouac wrote that Frank, "with the agility, mystery, genius, sadness and strange secrecy of a shadow photographed scenes that have never been seen before on film."86 Sarah Greenough eloquently articulated the impact of The Americans: With brilliant insight and economy, Frank revealed a country than many knew existed but few had acknowledged. He showed a culture deeply riddled by racism, alienation, and isolation, one with little civility and much violence. He depicted a society numbed by a seemingly endless array of consumer goods that promised many choices but offered no real satisfaction, and he revealed a people emasculated by politicians who were fatuous and distant at best, messianic at worst.87 Frank had identified some "symbols" he wanted to pursue, things that were seen everywhere but not looked at or examined, including flags, cowboys, rich socialites, jukeboxes, and politicians (Fig. 9-12).88 With The Americans, Frank revealed not just a society and a country that was simmering with tensions but also further articulated a new iconography that began with Evans. |

|

|

Fig 8: Robert Frank, Restaurant, U.S. 1 Leaving Columbia, South Carolina, 1955, gelatin silver print, 24.0 x 36.0 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

||

|

||

Fig 9: Robert Frank, Parade, Hoboken, New Jersey 1955-56, gelatin silver print, 23.0 x 34.9 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

When The Americans was published in America, the notion that it reflected a view of America and Americans was received with largely negative reactions. Both the content and the style of the images were criticised. In the May 1960 edition of Popular Photography various editors expressed their opinion in the form of individual reviews.89 The critics felt that Frank had not given a balanced view of America; he only portrayed one facet of the country. Evans' American Photographs received the same sentiment from Ansel Adams who claimed that "America is not that way; some of it is, but not all of it."90 The power of the images that Frank captured while on the American road demonstrates an image of society who was not yet ready to receive it.

Frank's style also came under fire. Departing from Evans' direct, sun-lit, dignified sense of place and moment,91 Frank combined dissonance and harmony, angst and fluidity, his images were fragmented with loose and casual compositions, often with blurry foregrounds creating a raw and aggressive feeling (Fig. 13).92 Yet the style of photography, the overwhelming sense of hostility, violence and alienation emanating from Frank's images is a reflection of what Frank was experiencing whilst on the road. Of the images he said:

I worked, but it came naturally to show what I felt, seeing those faces, those people, the kind of hidden violence. The country at that time -the McCarthy period - I felt it very strongly...It's pretty scary, and I think that somehow came through in the photographs - that violence I was confronted with.93

One of the most well known images of The Americans is Trolley, New Orleans (1955) (Fig. 14), which was the cover image of the 1959 American Grove Press edition. Depicting a cross-section of society, by age, gender and race, peering out of a segregated streetcar, it was taken only a few weeks before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus, one of the first actions of the civil rights movement. Trolley, New Orleans powerfully freezes an image of society bearing on an era of great historicity.

The road in Frank's photography exposes an iconography of American popular culture consisting of signage, jukeboxes, diners and other detritus and services that sprung out of being on the road. He also depicts a society through photographs, its people and vernacular politicises the view from the road in a way that is not overt but rather detached. The Americans is an epic journey of a country on the cusp of change and the tensions leading to that change - race relations, civil rights, the rise of consumerism - are powerfully captured by Frank. In this series the road organically acts as a conduit to this America.

|

|

|

|

|

The Road Heads in Different Directions: the 'ordinary' and personal artistic expression

Though photography on the road began as an exploration of national identity, during the 1960s and 1970s the idea of the photographic search for America evolved into "a purely personal or privately artistic expression."94 Lee Friedlander (b. 1934) explored the direction American photography was taking: "the personalising of the documentary aesthetic, the shifting of the delicate balance between record and interpretation toward expression."95 His images of street scenes taken as he drove around towns of America captured the social landscape yet the composition of intersecting verticals and horizontals (Fig. 15,16) are, as Rathbone argues, Friedlander's way of interpreting the visual havoc the car and its accompanying developments rendered on the American scene.96

|

|

|

|

|

The attention Friedlander paid to the ordinary is inherited from Atget, Evans and Frank whose influence on Friedlander is apparent in the enduring lesson that "the most ordinary thing - precisely because it is ordinary - can be made to speak through the vernacular language of photography."97

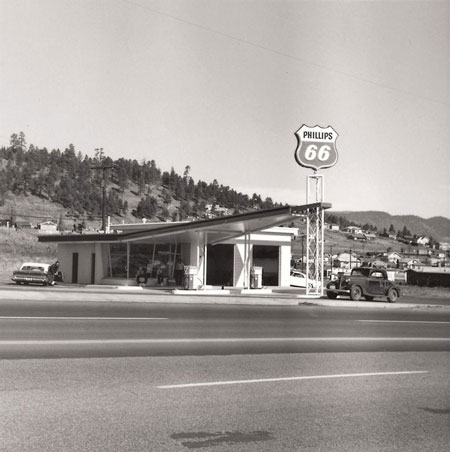

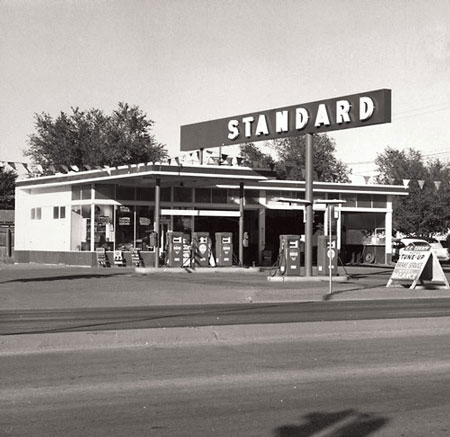

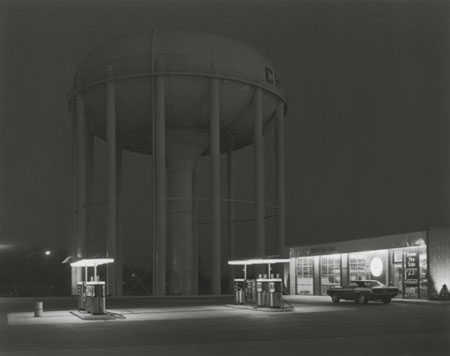

In the road photography of Edward Ruscha (b. 1937), the vernacular, in terms of ordinary Americana, was distilled even further. Ruscha explored multiple images with series that developed into a "systematic inquiry with clarity of purpose" which had little to do with relating a journey or depicting a society. His Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) was an exercise in typology, literally twenty-six images of gasoline stations (Fig. 17,18).

|

|

|

|

Fig 18: Edward Ruscha, Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, 1962 from Twentysix Gasoline Stations, 1963, gelatin silver print, 12.5 x 12.9 cm, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York |

Ruscha photographed ordinary roadside filling stations on several trips travelling on Route 66 between Los Angeles and Oklahoma, taking in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, and published them in a book with just the photographs and captions noting the locations. The stark, minimalist nature of the series is a vast departure from the preceding road photography of Evans, Frank and even Friedlander. The Americans had a strong impact on Ruscha yet he admits that the imagery does not necessarily translate into any direct influence on his work,98 rather it is Frank's rejection of an artful aesthetic rather than subject matter that is evident in Ruscha's images.

Ruscha, like Frank, factually documented America and his style not only reflected the mood of his generation but various artistic movements as well.

Dave Hickey believed that in the same way that Jack Kerouac "nailed the ecstatic, beatnik Road," Twentysix Gasoline Stations "nailed the Pop-Minimalist vision of the Road" for his generation through "realms of absence - that exquisite, iterative progress through the domain of names and places, through vacant landscapes of windblown, ephemeral language."99 Wolf argues that the absence of the usual linear trajectory of a road trip (Ruscha selected images based on their graphic qualities and placed them accordingly) points to the use of the camera as a recording device rather than an expressive tool.100

|

|

But whilst Ruscha is recording in a detached way gas station after gas station, his selectivity in which images are published and in which order is not purely documentary but expressive. Ruscha manages to evoke from the repetitive banality of gas stations a sense of the banality of life, earmarked by regular injections of fuel that keep people going.

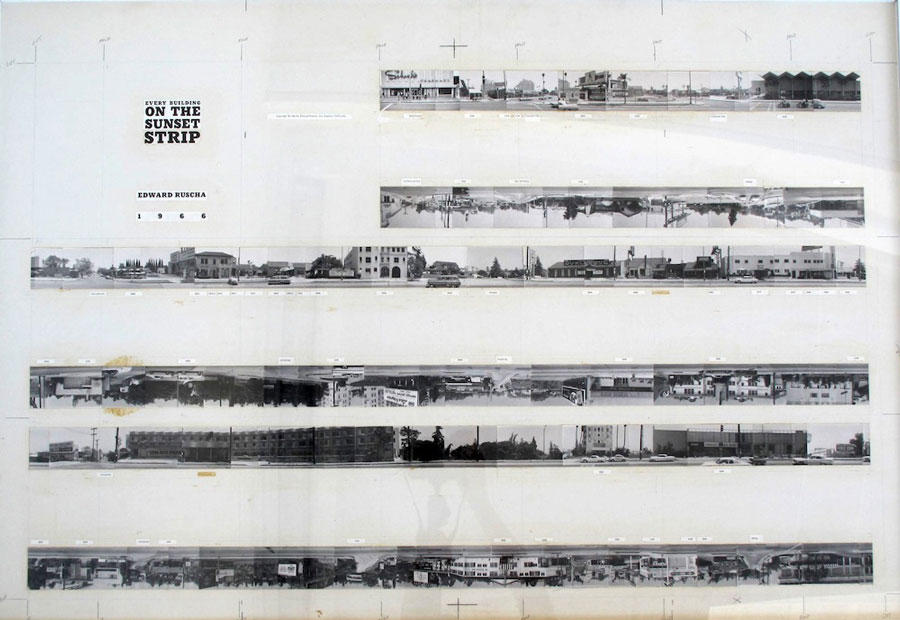

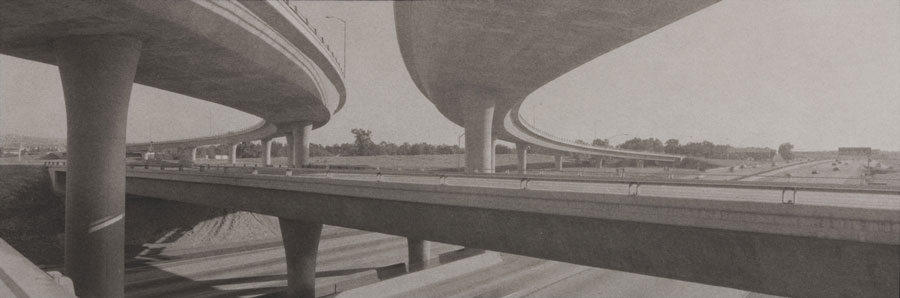

Ruscha's later published photographic road series, Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966),101 is another typological exercise and one that simultaneously speaks of contemporary urban existence and deep-rooted American beliefs of the frontier. As self-explanatory as Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Every Building on the Sunset Strip depicts just that, every building on the Sunset Strip, a section of Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood (Fig. 19).

Ruscha mounted a 35mm camera to a car, attached a motor drive102 and shot a continuous strip of black and white motion picture film.103 The deadpan execution emphasises the prosaic and redundant nature of the commercial strip104 whilst also depicting a period of extraordinary growth and urban sprawl.105 Yet the series also harks back to an older time in American lore, that of the Western. Photographed at high noon, the buildings are flattened with minimal shadowing to provide dimension. Ruscha likens it to a Western town, "a storefront plane of...just paper...everything behind it is just nothing."106

The idea linking urban sprawl to notions of the frontier marks a progression of industrialisation. That Ruscha had first attempted to photograph this series on foot before succumbing to the automobile and the road107 only strengthens the notion of industrial progression than mankind has to conquer and exploit for their own benefit.

However, Ruscha's photographic journeys on the road are still about capturing and depicting aspects of American society and character but this is not done through people and experiences, instead architecture and spaces devoid of people are given a voice. Twentysix Gasoline Stations represents the life force of automobiles that enable mobility and freedom to their human occupants whereas Every Building on Sunset Strip freezes in time the idea of an American West as a frontier, set against the reality of contemporary culture.108

Ruscha's dramatic departure from traditional road photography is made apparent by his views on his work. Ruscha stated that "one of the purposes of my books has to do with making a mass-produced object...My pictures are not that interesting, nor is the subject matter. They are simply a collection of 'facts'; my book is more like a collection of 'readymades.'"109

The Road in Colour and Beyond

During the 1970s a major shift occurred in art photography, the emergence of colour. By this time the status of photography as an art form had risen and was considered almost equal to the other arts such as painting and sculpture,110 but this was largely due to the medium reducing itself to the almost abstract clarity of black and white.111 The art world was prejudiced against colour, considering it to be the hallmark of commercial photography.112 Developments in technology introduced in the 1970s meant that colour was able to be gauged and controlled by photographers more accurately.113

Colour photography practice had been growing since the advent of Polaroid cameras, small Kodak Instamatics and cheap colour processing, and with colour television and broadcasts becoming standard by the 1970s, awareness of two-dimensional colour images of everyday life increased.114 That black and white photography had been associated with both serious photojournalism and art photography meant there was a cultural resistance to colour photography115 which was combated by dedicated exhibitions of colour work.116 The photographic road trip went along for the ride and also burst into colour in the 1970s.

The road and the renaissance in colour photography are closely linked. In their critical history of American photography, Green and Friedman argued that the style and subject matter of colour photography in the 1970s derived from American street photography and, more specifically, Walker Evans, rather than from previous colour photography.117 A large retrospective of Evans' work was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1971 which would have reasserted Evans into the public and artistic consciousness.

William Eggleston and Stephen Shore were both active in the colour renaissance of the 1970s, closely followed by Joel Sternfeld and Richard Misrach,118 with Eggleston and Shore helping define the American vernacular of the period.119 Philip Gefter proposed that "if Walker Evans and Robert Frank established an 'on the road' tradition in photography, then Stephen Shore ranks among their natural heirs."120

Shore's series American Surfaces is a throwback to the kind of road photography of Evans and Frank but in rich colour. It combines the two trends in photography of the 1970s - the use of colour, and an interest in ordinary town- and cityscapes.121

American Surfaces has close parallels to traditional road photography in terms of being a result of a photographic road trip that depicts aspects of American society. Shore took his pictures over a twenty-two month period over 1972-1973 and in 1999 American Surfaces was published comprising of 77 plates. Beginning in New York City he drove to Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, the deep South and Southwest, Arizona, Oklahoma, Chicago, Colorado, New Mexico and Michigan.

However Shore did not just photograph motifs usually associated with road photography such as the view from the car, signs, people and towns for example, but also less common subject matter such as the meals he ate, interiors of the motels and diners he frequented, open refrigerators, toilets, condom vending machines and oddities such as a nude store mannequin in bed (Fig. 20-25). Shore described the work as "a visual journal of a trip across the country...I was interested more in the ordinary..."122

|

|

|

Fig 20: Stephen Shore, Washington, District of Columbia, November 1972, Type C colour photograph, 9.7 x 12.7 cm, reproduced in Stephen Shore, American Surfaces. London: Phaidon Press, 2005 |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig 22: Stephen Shore, New York City, New York, September-October, 1972, C-print, 12.5 x 18.75 cm, reproduced in Stephen Shore, American Surfaces. London: Phaidon Press, 2005 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Susan Sontag stated that "to photograph is to confer importance"123 and like Frank, Shore was 'monumentalizing' what was generally not considered worthy of being elevated to art.

Rathbone contends that Shore set out to prove that the documentary tradition could endure in colour without losing integrity.124 The deadpan execution of the images presents an ambivalent view of American culture, however Shore is doing more than being an objective documenter of what he sees on his journey. The camera is turned inward metaphorically and the journey is an extremely personal one, one he describes as "recording my life."125

Lynne Tillman believes that Shore's photographic diary "strips being to an existential loneliness: you are what you do, where you go, and what you spend, not what you feel or think, or what you think about what you're doing."126 The philosophical remnants in Shore's imagery differentiates it from Evans and even Frank yet the essence of the road trip as a discovery is still present.

However the series also contains significant elements of the generation of road photographers after Frank who used the road as a means to explore personal artistic processes. Similarly to Ruscha who tapped into Pop-Minimalism and Conceptual art through his desire to document and utilisation of typology to express his artistic vision, exploration of various artistic influences are evident in Shore's series. Shore became interested in Conceptual art after discovering Ruscha's Every Building on the Sunset Strip, promptly acquiring all of Ruscha's books.127

Ruscha's 'documenting' of the Sunset Strip had a strong influence on Shore who intended American Surfaces to be a "document of documents."128 Shore's fixation on the meals he ate, crumpled bed linen, and the banal minutiae of life is also linked to conceptual photography of the late 1960s-early 1970s and the impulse to photograph everything and everyone."129

The serial nature or American Surfaces stems from Shore's time with Andy Warhol. In his teens Shore worked at The Factory and witnessed Warhol working with a 'serial view' which led to Shore thinking about images in terms of serial projects.130 The saturated colours also speak of a Pop sensibility. The addition of colour to road photography added elements of richness, sensuality, and surprise,131 literally bringing images to life and into the now.

Like Frank, Shore understood that the sum total of their series was more than just exposing aspects of America but also a personal portrait.132 The photographic road trip that Shore embarked on was an extremely personal one, the viewer accompanies Shore every step of the way and he allows a glimpse not only into his life but that of the archetypal traveller on the road.

|

|

|

Fig 26: Jeff Brouws, Mobil, Highway 395, Inyokern, California, 1990, |

|

|

||

| Fig 28: Catherine Opie, Untitled till (Freeways), 1994, platinum print, 5.7 x 17.1 cm, Regen Projects, Los Angeles |

Road photography continued on throughout the 1970s and beyond in both colour and black and white.

Many other photographers explored the road in photography such as Jeff Brouws (b. 1955), influenced by Evans, investigated America's secondary highways133 (Fig. 26); George Tice (b. 1938) who photographed from the road of his hometown New Jersey the vestiges of American culture on the cusp of disappearing,134 (Fig. 27); and Catherine Opie (b. 1961) who explored notions of structures as icons and relics of human presence through images of the Los Angeles highway system135 (Fig. 28), to name a few.

Lee Friedlander revisited the road 1995-2009 but this time did not leave the vehicle. Friedlander shot from the car deliberately including automobile elements to create juxtapositions, dissections and fractured images. A collection was published in 2010 titled America by Cor136 and exhibited at the Whitney Museum.

But in American Surfaces the facets of American road photography are encompassed. It has its roots in the original tradition of American road photography of Dorothea Lange and the FSA commissions in terms of using the road to capture a side of America minus the didactic aspect. Like Walker Evans, Stephen Shore captured his journey across America photographically, as well as the aspects of American vernacular that Evans began to explore but Robert Frank was to really exploit in The Americans.

Shore's series also demonstrates the influence of artistic movements of the 1960s and 1970s, experimenting with Conceptualism and Pop Art as well as making a contribution to the advancement of photography in the arts - the promotion of colour photography as fine art. American Surfaces thus encapsulates the development of the road in American photography from being a tool to 'discover' America to being a site of personal artistic expression.

As demonstrated in this chapter, the road has a distinct tradition and development within American photography. The next two chapters will investigate whether there is a similar tradition and development of road photography in Australia.

- Belinda Rathbone, Curator's talk, Robert Lehman Art Center, 2 April 2010, Brooks School, accessed August 27, 2010, http://www.brooksschool.org/podium/default.aspx?t=204&nid=539038

- On the Road: A Legacy of Walker Evans, The Robert Lehman Art Center, Brooks School, North Andover, Massachusetts, April 2 -June 12, 2010.

- Paul Simon, "America" from the Simon & Garfunkel album Bookends, 1968. The correct lyric is "they've all gone to look for America."

- Belinda Rathbone. "Overview" of On the Road: A Legacy of Walker Evans, Robert Lehman Art Center, accessed August 27, 2010, http://www.lehmanartcenter.com/evans_exhibit/evans_01.html

- Eyerman and Lofgren, 53.

- Belinda Rathbone, On the Road: A Legacy of Walker Evans (North Andover: The Robert Lehman Art Center, 2010), np.

- Laufer, "In Search of America," 12.

- Charles Hagen, introduction to American Photographers of the Depression: Farm Security Administration Photographs 1935-1942 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), np.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, "Rodeo, New York City, 1955," 77?e Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed August 14, 2010, http://www.metmuseum.Org/toah/works-of-art/1992.5162.3

- For example see Feeney and also Laufer, fn 28.

- Jack F. Hurley, Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the development of documentary photography in the thirties (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972), 32.

- Hagen, introduction, np.

- Hagen, introduction, np.

- Hurley, vii.

- Hagen, introduction, np.

- Hurley, 122-24.

- Hagen, introduction, np.

- Sante, "Robert Frank and Jack Kerouac," 202.

- Laufer, "In Search of America," 12.

- Robert Coles, Dorothea Lange: Photographs of a Lifetime (New York: Aperture, 1982), 12.

- Coles, 36.

- Hurley, 52.

- American Photographs by Walker Evans exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1938.

- Walker Evans. American Photographs (fiftieth-anniversary edition). New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988.

- For examples of just some of the photographers in whose work the influence of Walker Evans can be observed see Institute of Contemporary Art. The Presence of Walker Evans: Diane Arbus, William Chrlstenberry, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Helen Levitt, Alston Purvis, John Szarkowski, Jerry Thompson, June 27-September 3, 1978. (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1978).

- Laufer, p. 23.

- Walker Evans. Walker Evans (fiftieth-anniversary edition) (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971), 14.

- Evans, Walker Evans, 14.

- Evans, Walker Evans, 16.

- Laufer, "In Search of American," 24.

- Alan Trachtenberg, "The Artist of the Real," in Institute of Contemporary Art, The Presence of Walker Evans: Diane Arbus, William Christenberry, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Helen Levitt, Alston Purvis, John Szarkowski, Jerry Thompson, June 27-September 3, 1978 (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1978), 18.

- Carl Van Vechten quoted in Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History: Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), 246.

- Hurley, 140.

- Coles, 20.

- Hurley, 140.

- Martin Staples Shockley, "The Reception of The Grapes of Wrath in Oklahoma," American Literature 15, no. 4 (Jan., 1944): 351.

- David Wyatt, introduction to New Essays on The Grapes of Wrath, edited by David Wyatt (Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1990), 3.

- Laderman, 27.

- Laderman, 28-9.

- Laderman, 29-31.

- Hurley, 140.

- 74 Pare Lorentz. U.S. Camera 1 (1941): 93-116, quoted in Beaumont Newhall, History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1997), 148.

- Robert Frank, The Americans (Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications, in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1993).

- Edward Ruscha, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (Alhambra, California: Cunningham Press, 1962).

- Stephen Shore, American Surfaces (London: Phaidon Press, 2005).

- Rathbone, "On the Road," np.

- Peter Galassi, Friedlander (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2005), 33.

- Jerry L. Thompson, Walker Evans at Work (New York: Harper and Row, 1982), 98.

- Philip Gefter, "Travels with Walker, Robert, and Andy: On Stephen Shore," in Photography After Frank (New York: Aperture, 2009), 19.

- Sarah Greenough, "Resisting Intelligence: Zurich to New York," in Greenough, 37.

- Constance W. Glenn, "Frank, Robert" in Oxford Art Online. Grove Art Online, accessed August 30, 2010, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T029714

- Rathbone, "On the Road," np

- Rathbone, "On the Road," np. The Guggenheim Fellowships are American grants that have been annually awarded since 1925 by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those who have "demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts." John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, accessed August 13, 2010, http://www.gf.org/

- Jack Kerouac, introduction to American Photographs, by Frank, 5.

- Sarah Greenough, introduction to Looking In, by Greenough, xix-xx.

- Sarah Greenough, "Disordering the Senses: Guggenheim Fellowship," in Greenough, 120.

- Les Barry concluded that the book was an attack on the United States, Bruce Downes believed that it contained "images of an America seen by a joyless man who hates the country of his adoption" and that Frank is "a liar, perversely basking in the kind of world and the kind of misery he is perpetually seeking and persistently creating," whilst James M. Zanutto described the book as "a sad poem for sick people. Yet some critics had a more balanced view, admitting that Frank has created many pictures of beauty as well as the not so beautiful, lovely and evocative pictures of an intense personal vision, but lamented the blurriness, grainy quality and general sloppiness of the images. Les Barry et al., "An off-beat view of the U.S.A.: Popular Photography's editors comment on a controversial new book." Popular Photography (May 1960): 104-05.

- Douglas R. Nickel, "American Photographs Revisited," American Art 6, no. 2 (Spring, 1992): 86.

- Tod Papageorge, Walker Evans and Robert Frank: An Essay on Influence (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1981), i.

- Greenough, introduction, xx.

- Robert Frank quoted in Photography within the Humanities, edited by Eugenia Parry Janis and Wendy MacNeil (New Haven: Danbury, 1977), 65, cited in Leslie Baier, "Visions of Fascination and Despair: the relationship between Walker Evans and Robert Frank," Art Journal, 41, no. 1, Photography and the Scholar/Critic (Spring, 1981): 60.

- Laufer, "In Search of America," 232, 300.

- Jonathan Green, American Photography: A Critical History 1945 to the Present (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1984), 106.

- Rathbone, "On the Road," np.

- Galassi, Friedlander, 33.

- Edward Ruscha in conversation with Sylvia Wolf, June 2, 2003 in Sylvia Wolf, Ed Ruscha and Photography (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art/Steidl, 2004), 20-21.

- Dave Hickey, "Theory: Edward Ruscha: Twentysix Gasoline Stations, 1962 - Photographer (1997)" Artforum (January, 1997). American Suburb X, accessed August 8, 2010, http://www.americansuburbx.com/2009/10/theory-edward-ruscha-twentysix-gasoline.html 100

- Wolf, p. 115.

- Edward Ruscha, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966, artists book, 18.0 x 760.7 cm (extended), National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

- A motor drive is a device that advances the film automatically to allow for rapid fire exposures.

- Wolf, 139.

- Rathbone, "On the Road," np.

- Wolf, 141.

- Ruscha quoted in Wolf, 140.

- 107 Wolf, 139

- 108 Wolf, 140.

- Edward Ruscha quoted in Mary Richards, Ed Ruscha (London: Tate Publishing, 2008), 34.

- Institutions actively collected photographs from early 20th century however it wasn't until the 1950s onwards that there was an increase in public and private galleries focusing on photography. The Limelight Gallery in 1954, Carl Siembab's gallery in 1961 and the Witkin Gallery in the 1970s were highly influential as was the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House. Major photographic exhibitions increased awareness of photography as art such as the landmark Family of Man in 1955, a solo Lee Friedlander show in 1963, New Documents in 1967 and a solo Diane Arbus show in 1972 and New Topographies in 1975 for example. John Szarkowski, curator of photography at MoMA, strived to get the museum-going public to think differently about photography. The corporate world also began collecting photography in the 1960s and 1970s including companies like Hallmark, Polaroid, Chase Manhattan Bank and Gilman Paper Company.

- Aaron Betsky, foreword to Starburst: Color Photography in America 1970-1980, by Kevin Moore (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2010), 7.

- Gefter, "Travels with Walker," 17.

- Kodak introduced materials in the 1970s that were unprecedented in terms of fidelity, range of control and luminosity. The availability of negative film such as Vericolor and paper such as Ektacolor allowed for close approximation of colour, even in bright daylight. Green, p. 189.

- Green, 185.

- Kevin Moore. "Starburst: American Color Photography in America 1970-1980" in Moore, 8.

- Marie Cosinda's colour photographs were exhibited at the George Eastman House and the Museum of Modern Art, New York in the late 1960s and in 1976 John Szarkowski declared his exhibition of William Eggleston dye-transfer prints as "the discovery of colour photography." Green, 186-87.

- Green, 185.

- Rathbone, "On the Road," 17.

- Bob Nickas, introduction to American Surfaces by Stephen Shore (London: Phaidon Press, 2005), 6.

- Gefter, "Travels with Walker," 17.

- Mary Christian, "Shore, Stephen" in Oxford Art Online. Grove Art Online, accessed August 2, 2010, http://www.oxfordartonline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/art/T078369

- Nickas, introduction, 8-9.

- Susan Sontag, On Photography (London: Penguin, 2008), 28.

- Rathbone, "On the Road," np.

- Shore quoted in Nickas, introduction, 8.

- Lynne Tillman, "Accounting for Days," Artforum 45, no. 10 (Summer, 2007): 460.

- Moore, p. 17.

- Tillman, 460.

- In 1971 conceptual artist Douglas Huebler declared he wanted to photography "everyone alive." Nickas, introduction, 10.

- Gefter, "Travels with Walker," 18.

- Rathbone, "On the Road," np.

- Moore, in Moore, 18.

- Jeff Brouws, "About," Jeff Brouws, accessed August 26, 2010, http://www.jeffbrouws.com/about/main.html

- Getty Museum, "George Tice," The Getty Museum, accessed August 26, 2010, http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artMakerDetails?maker=3906

- Jennifer Blessing, "Catherine Opie: American Photographer," Guggenheim Museum, accessed August 26, 2010, http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/exhibitions/past/exhibit/2470

- Lee Friedlander, America by Car (San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2005).

>>>>> next: Chapter Two

Home-Page / Introduction / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / Conclusion / List of Images / Bibliography

If there are amendments or corrections you wish to suggest - please make contact.

• photo-web • photography • australia • asia pacific • landscape • heritage •

• exhibitions • news • portraiture • biographies • urban • city • views • articles • • portfolios • history •

• contemporary • links • research • international • art • Paul Costigan • Gael Newton •