|

|

Home-Page / Intro & Acknowledgements / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / conclusion / illustrations / references

Landscape of Virtue:The Life and Work of Photographer Wesley Stacey – Ziv Cohen 2003

Chapter two:Photographer Wesley Stacey - childhood and adolescence

Wesley Stacey was born in 1941 in the Sydney suburb of Fairlight to Edward Wesley, an English migrant working as a bank clerk in Sydney, and Alice Steele from Rockhampton. Sister Sandra was born in 1943 (Stacey 2003 a).

Stacey's childhood was influenced by a shifting home environment between the Sydney northern suburbs of Manly, Balgowlah and Cammeray. The Second World War and an adolescent asthmatic condition shadowed Stacey's early life. He recalls 'when I was 2 or 3 I knew there was a war on – I was shown the 'flak' clouds over the harbour – and heard the guns' (Stacey, 2003 b). Reoccurring domestic conflicts between his parents and incessant arguments with his father were dominant during his early life, evolving into a formative element of his later personal and professional development. Yet the absence of a harmonious family environment does not conclude that a child might lack all rational and emotional faculties, as Sherman claims, "the child's acknowledgment of the parents' love and trust engenders a willingness to learn from them and a readiness to comply (bold mine)..'(Sherman, 1989, p. 152). Here, suggestively, lie the roots of Stacey's extraordinary capacity to question, challenge and reject presumptions, a quality so evident throughout his life and photographic career, a matter that will be demonstrated in the following thesis. This aside, Stacey's childhood is recorded as typically Australian: playing with toy cars, trips to the zoo, fishing in Sydney harbour, reading adventure stories, taking outings to the nearby bush and interstate travelling to visit family relatives. Early exposure to art in the form of painting was prevalent through Wesley's father Edward (Ted) who maintained a hobby of painting on Sundays and the occasional painting excursion, accompanied by young Wesley, which left him with memories of walking up the sandstone slabs of the heath country in Balgowlah. Stacey discovered photography during his early teens at Trinity Grammar Boarding School, which he attended between the ages of twelve and fourteen. During these years his exploration of photography progressed with cousin David Stacey, coinciding with widening voyages around Sydney by public transport and his exposure to the increasingly popular American film. Further undertakings of photographic techniques and adventures included developing and printing in the school darkroom, the construction of a Pinhole view camera and an attempt to photograph the Queen's visit in 1953, an event that brought to light the limitations of his Brownie Box camera. During his time at boarding school, Stacey was sent on a Christian boys camp to Lake Munmorah where he leaped at the chance of involving himself in a host of newly found activities, including camping in tents, camp-style cooking, night games and sing-alongs around the fire. These activities were freedoms that stimulated the spontaneous writing of his first poem, illustrated with a watercolour painting (Stacey 2003:a). Stacey remembers his mother's encouragement for his artistic inclination:

In 1953 the Stacey household had separated, and Wesley began living with his father, grandmother and sister in Cammeray, maintaining only limited contact with a small extended family of uncles and aunts. The Stacey's were not a church going family; however, church values were an aspect of their lives and Stacey attended Sunday school and participated in choir singing. During 1954-6, Wesley attended Mosman Intermediate High school; during this time, his ties to the Anglican Church began to tighten, and throughout his late teens to his mid twenties he considered himself a devout Christian (Stacey 2003:a). It is much debated and often doubted whether the Christian church's self-proclaimed values of loving, caring and sharing translates into political ideology and influencing institutional public policies. Yet the role of the church in the shaping of Australia's social consciousness by informing and moulding individuals and communities is well accepted. While history suggests religion should be modest in its claims for social righteousness after having participated in some dark chapters of humanity, Australian history can show how the Christian church participated in many socially and politically valid agendas. Fred Chaney writes:

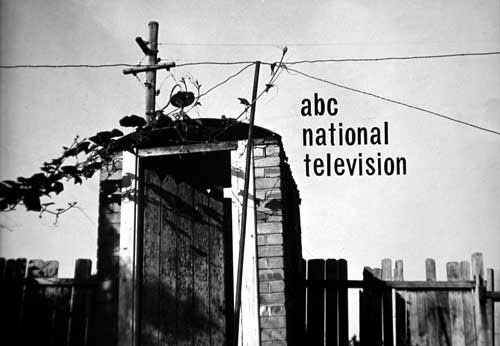

Independence and Professional pursuitAt the age of 15, in the year 1956, Stacey left school at the intermediate stage and commenced a working life as an apprentice in a silkscreen-printing factory, additionally pursuing the skills of lettering and drawing at Ultimo Technical College. The work in the silk-screening factory consisted of manual stencil cutting, ink mixing and painting; work that required high attention to detail. Gaining further independence, Stacey purchased a motor scooter at the age of 16 and bought his first car at 18: a Fiat Bambino 600. After three years in the silk-screen factory the business was sold and Stacey found work with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) in Gore Hill. He began with working on the floor as a 'studio hand' constructing, removing and storing props. Stacey then moved up into the graphics department assisting in the production of background boards, posters and other graphic materials.

Whilst Stacey's technical skills were sharpening, he was also making contacts within the industry as well as developing a growing vocabulary of literature, art and social skills. The ABC environment was a fertile ground where artists and craftsmen were engaging communally in culture and media research and production. Stacey recalls the support and encouragement from co-workers whom he admired. Social activities intertwined with work: lunch at the pub, wine-sipping under the Harbour Bridge, and debates around the tombstone of Bernard Holtermann in the nearby cemetery of Gore Hill. During one of his projects at ABC, Stacey was exposed to the Holtermann photographic collection that was discovered in the early 1950's in a garden shed in Willoughby, an encounter that stimulated a growing interest in historic photography. During these formative years Stacey's photographic skills and enthusiasm were also developing. He was strongly encouraged by the head of the ABC's graphics department Kevin Connor and became acquainted with Australia's then current art and painters. Stacey has noted painters Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd and Russell Drysdale as his early artistic inspirations, and their aesthetic and conceptual influences are evident in his future work. (Stacey, 2003 a) This group of prominent innovative Australians painters were particularly potent in their contribution to the Australian social consciousness during the 1930s and 40s, a time of war and depression. Known as the Angry Penguins, due to their association with a cultural publication named Angry Penguin, Nolan, Boyd and other 'social realists' responded to the horror of wars and what they saw as the degeneration and barbarism of twentieth-century sophistication, by producing disturbing images of death and devastation. On this subject Donald writes:

From this bleak existential perspective, Nolan, Boyd and Drysdale later became primarily occupied with exploring and painting the Australian landscape; an environment unscarred by war and still in possession of the innocent and therapeutic gifts of a relatively unspoiled nature. However, their distinctive style of painting continued to posses a somewhat sombre and realistically awkward view of Australia, challenging the traditional 'attractive' school of landscape painting and empowering a new generation of Australian art (Donald, 1990, pp. 114-118). Stacey's technical photographic knowledge was also continuing to develop; an early significant contribution was made to his acquirement of knowledge by his photographic colleague John Cox, whose methods in dealing with the Australian landscape and architecture left a lasting impression on Stacey. New aesthetic inspiration together with aspects of classical culture and issues of architecture and landscape architecture was gained from the book Italian Townscape Stacey discovered in 1960. It was in that time that Stacey was advised by his colleagues at the ABC to put down the charcoal and concentrate on a photographic career, thus leading to his first exhibition of photography. (Stacey, 2003:a)

First Exhibition Stacey's first exhibition of photography occurred in 1964. At the age of twenty-three, Stacey was deeply involved with the Christian faith and church activities. His passionate and contemplative life-view was strongly reflected in the exhibitions subject matter, representation mode and choice of names for his photographs. The exhibition, "A Showing of Photographic Panels" at Goldstein Hall in the University of New South Wales in June 1964, featured 13 black and white photos carrying titles such as Mix Feelings on the Crucifixion, Rejected creatures and Dark flood. 'A certain teenage intensity can be seen in early images that reveal his religious concerns' wrote Newton (1999, p. 2) about this period. In his artist's statement, the young Stacey wrote: *I find in photography a means of expressing the feelings of the poet and the artist. I hope to communicate by creative selection - the precise interpretation of which lies with the observer' (exhibition almanac, Art Gallery of New South Wales library archive).

At the age of twenty, Stacey had left his father's home and soon after married Barbara Wilson of Summer Hill. Together they lived in a rented flat in Lewisham until taking his long service leave from the ABC, during which they sailed to England together aboard the Canberra in the autumn of 1964.

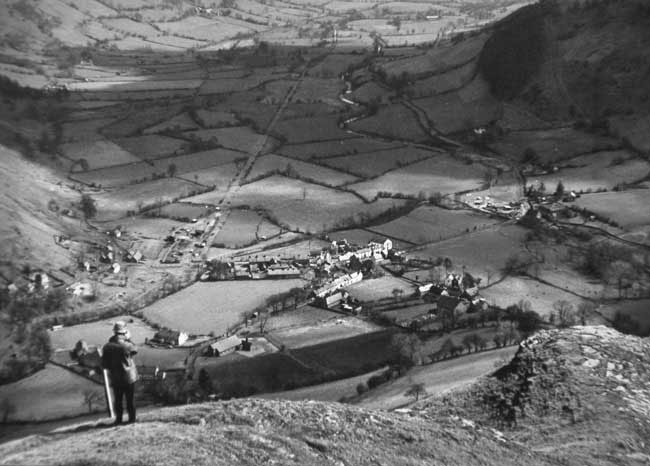

OverseasStacey stayed in London for two years where he continued to work in television graphics production, this time for the British Broadcasting Corporation. During his time in London, assignments involving photography and photojournalism were of growing frequency and Stacey travelled throughout England, Scotland and Wales, photographing architectural and landscape subjects together while pursuing a newly acquired enthusiasm for wine. In 1965, together with a group of friends, Stacey travelled in a campervan through France, Italy and Germany, a journey similarly centred on the pursuits of sight-seeing and wine tasting. Back in London, Stacey's professional development continued to flourish. A meeting with the commissioning editor of the Thames and Hudson publishing company proved to play a key role in his career in the years to come, whilst meetings with artists and poets further broadened his cultural and intellectual horizons (Stacey, 2003:a).

Stacey left for England armed with his Australian photography on the off chance he might have it exposed abroad, which he did. In 1965 he exhibited two large photographic panels and some 50 smaller photos in the Royal Institute of British Architects, an exposition of architectural and landscape photography that was well received and paved the way for numerous photographic assignments he received while in England. It was in London in 1965 that Blake, Stacey's first and only child, was born (Stacey, 2003:a).

Returning to AustraliaThe year 1966 saw Stacey return to Sydney as an experienced and inspired photographer seasoned by overseas travels and work experience. 'My mates in London asked me why I was returning to Australia. The only way I could put it was that I was returning to my (Australian) roots' (Stacey, 2003:b). While maintaining work and social associations with the ABC and helping to develop the organisation's photographic facilities, Stacey launched himself in Sydney as a freelance commercial photographer with great versatility and proficiency, acclaimed by critics at the time as setting new standards in Australian magazine photography:

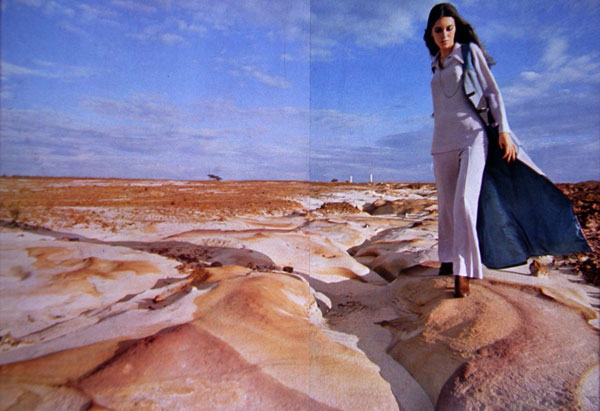

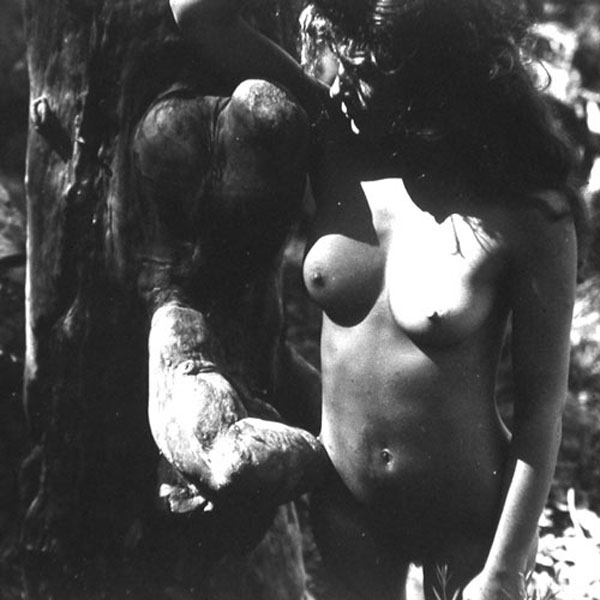

Stacey photographed all kinds of subjects and purposes from fashion to naked women, action-sport to baby health, diversity he perceived as valuable:

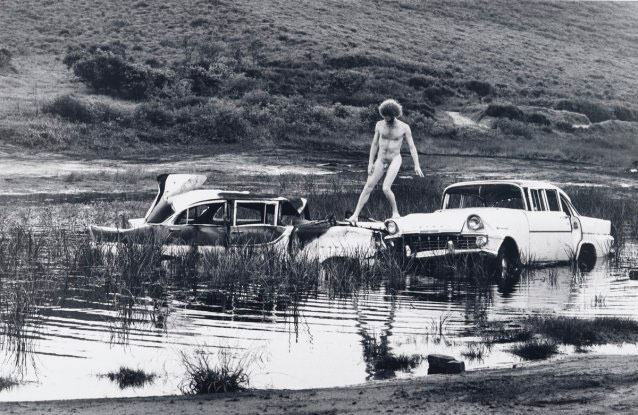

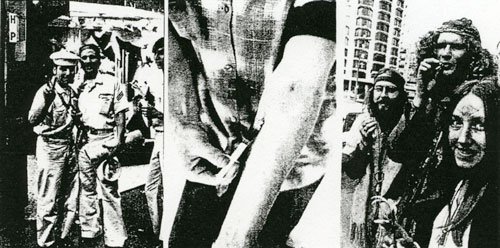

In this same interview for Camera World, Stacey also referred to his recently acquired habit of drinking wine as an instrumental component of his creative and operational processes. When approaching a new assignment such as photographing a model, he says: I usually take a bottle or two of wine with us... I find that a drink usually relaxes both of us and I can learn something about her, something I can relate photographically' (ibid). Following Stacey's progress to the post of pictorial director and editorial photographer of Powell magazine publishers, Stacey spent the rest of the 1960's enjoying commercial success. He immersed himself in the vibrant social scene of Sydney's art and fashion circles, where even his physique seemed to fit the mould: 'Physically, Wes Stacey could almost be the epitome of the intense, passionately committed photographer today. Stacey is lean and tall, with a face crowned with a head of the most preposterously curly hair' (McFarlane, 1968, pp. 18-21). The world of commercial photography alone did not satisfy Stacey and, parallel to fashion photography and photojournalism for print media, his artistic development continued to explore new expressions and subject matters. His rejection of church values and all imposed conventions, together with aesthetic influences of the period were reflected in Stacey's photography through growing stylistic experimentations of contrasting graphic qualities of black and white spaces and lines (Newton, 1991). As an offset of his fashion photography came his contribution to one of the earliest contemporary Australian photographic exhibitions, The Australian Nude, which took place in the newly founded Gallery A in 1967.

Gallery A was a community-based exhibition space heralding the Australian contemporary arts renaissance of the 1970s which saw dramatic changes in the content and forms of visual and performance arts. Dominated by the conceptual art movement, in addition to an increased affiliation between the arts and political and social movements. These changes were reflected in many social movements of the time including the women's liberation movement, the peace movement in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and indigenous rights. Another significant cultural phenomenon of the 1960s was the 'hippy' lifestyle and attitude of young generation Australians, young Stacey among them. Enforced by growing television popularity and the multi million dollar American movie industry, this cultural trend, epitomised by long hair, blue jeans and marijuana smoking, culminated in the Australian version of the Woodstock festival, the Aquarius Festival, at Nimbin in 1973. Subsequently there was a migration of many artists seeking an alternative lifestyle in rural regions outside of the metropolitan centres of Sydney and Melbourne. At the age of twenty-seven, young Stacey actively participated in most of the above social phenomena of the period, producing many publications and exhibitions of photography, contributions to art and cultural discourses, smoking pot and, most significantly, buying a large coastal property under community title in the far south coast of New South Wales (Stacey 2003:a). In 1971 Barbara and Wesley decided to end their marriage. He sees the separation from Barbara because of the strain on the freelance lifestyle and running around of the books production. Stacey wished that his son not be exposed to family tension the way he was (Stacey, 2003:b). Wesley moved away from North Shore suburbia and bought a house in the inner-city suburb of Leichhardt, dedicating himself to photography and art. In 1970 Stacey was invited by the celebrated photographer David Moore to share his studio in North Sydney: 'David was impressed by my book Rude Timber Buildings of Australia and wrote me a letter out of the blue invited me to use his studio which was great' (Stacey, 2003 :c). The studio in question became a legendary Sydney hothouse of creativity, a collective of iconic Australian professionals such Ian McKay & Partners Architects, Bruce Mackenzie Landscape Consultant, Gordon Andrews Consulted Designer, Roger Rogers Illustrator & Graphic Designer and David Moore Photographer. Located at 7 Ridge Street, North Sydney. In his tribute to David Moore after his recent death Bruce Mackenzie described the building and the atmosphere at the time:

Empowered by this inspiring environment, Moore and Stacey followed their later vision of the creation of an exhibition space in Sydney that would be dedicated to photography. Thus, Stacey, Moore, and a committee of like-minded photographers established the Australian Centre for Photography in 1973. The initiative coincided with the establishment of the newly founded Australian Council for the Arts in 1973, the first in a number of cultural organizations facilitating expositions and exposure for experimental and alternative artwork not represented in the commercial galleries. The ACP endowed photography and photographers with an appropriate space as well as respectable position within the Australian visual arts and is still in operation:

Stacey was involved with the centre in different capacities until 1975:

Architectural heritage and the vernacular architectureThe built form captivated Stacey from a young age, and from the late 1960's it began to return to the forefront of his work:

The 1960's saw the emergence of vernacular architecture as a significant, new and additional discourse to the disciplines of built environments and social sciences. Vernacular, the built form that is considered to be culturally and geographically intrinsic to its site and people was being interpreted and discussed in circles worldwide. The re-evaluation of existing vernacular architecture during the 1960s signified changing attitudes within existing modern practices of the architecture and landscape architecture disciplines, as expressed by Venturi et al in their comprehensive study Learning From Las Vegas:

Additionally, Modern architecture, in its strive for a new universal form dominated by logic, program and free from past experience, is blamed for excluding much of human tradition and its iconography, folk arts and crafts and popular culture. By critiquing Modern architecture's alienation from cultural traditions and history's lessons, those who call for the appropriation of principles of vernacular architecture in contemporary culture wish to create a better built environment, as '...it teaches us architects to be more understanding and less authoritarian in the plans we make for both inner-city and new development' (Venturi, 1972, pp. 3-7). In order to further understand the photography of Stacey in the late 1960s until the mid-1970s, and its relevance to the comprehension of vernacular architecture theory and its social significance, it will be contrasted here with the landscape photography of the Australian pastoral national image that dominated the scene until that time. Landscape art and, later, landscape photography in Australia has been traditionally associated with the pragmatic and psychological necessity of its European inhabitants to claim the land and market it to a growing national and international audience. The uncertainty produced by the First World War furthered the need, especially by men, to create a national tradition and identity that carried hope for a new future detached from the painful history they had recently experienced. The prevailing notion of Australia as terra nullius, together with an official and general denial of its penal history and the treatment of its original inhabitants, paved the way for a constructed vision of Australia where the landscape became a ready-made medium for the formation of the new national culture. The iconic pastoral image of Australia presented in a beautified pictorialistic style was used in Australia and abroad to cultivate and market a national aesthetic and moral attachment to a land once perceived in apathy and even dislike. The rural land itself, while presented as the nation's essence, was devoid of regional or geographic distinctiveness; instead, it was the human landscape that was celebrated, viewed as a landscape of capital and economic ambition rather then that of rural virtue. The purification of images to conform to a national symbolism was prevalent even in the work of modern photographers, such as Harold Cazneaux., where darkroom techniques were carefully used to remove distracting elements from otherwise idyllic pastoral scene. The advent of modernism did not challenge the continuation of national identity construction and its search for personal and individual expression; it maintained the conventional image of Australia as a generic and universal land rather than a distinct Australia in essence or appearance. In its inherent rejection of history as a model, modernity however dismissed the pastoral image of Australia in favour of another humanised landscaped the city:

The 1960s saw modem Australia looking back at its past through a process of revaluation and recognition of its social history, together with the discovery of certain forms, of architectural and landscape heritage that indeed were unique and intrinsic. This occupation with a newly discovered field of vernacular architecture coincided with growing criticism of suburban expansion transforming large tracks of the land into what was castigated by architect Robin Boyd as spiritual and aesthetic deserts (Duggan, 2001, pp. 71-79). The vernacular form of the built environment is closely tied to the history of the society that produced it, and in the face of a rapidly changing world this history An example of the ways in which history and past traditions are used to reflect present meanings can be found in the novel The Blood Vote by Jack Lindsay, in which the author has projected ancient Roman mythologies upon Australian contemporary conditions revealing history's organic and evolutionary nature, its place in the origin of the present and its role as an illuminating model; 'History is the saga of people's alienation from their true origin and their twisting attempt to return to if (Gillen, 1986, p. 200). The re-evaluation of Australian history in the face of damning revelations of the treatment of the Australian Aboriginal population in the past and present was a major contributing factor in the new search for an historical context upon which a redeeming future can be built. Adjoining the psychological and existential layers of individual and social consciousness, the traditional political and ideological structures with their reliance on constructed meanings also supported the new call to recognise and preserve landmarks and monuments of historic national value:

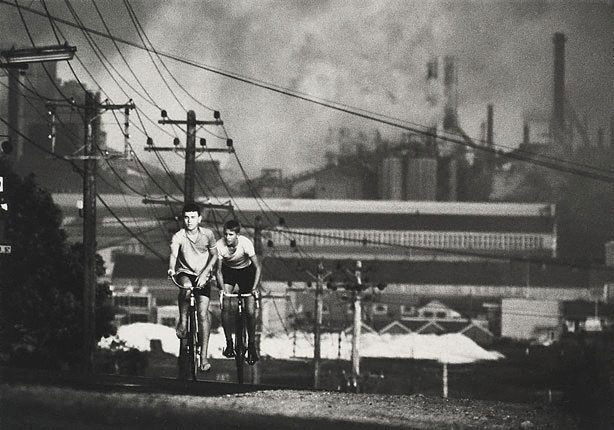

Photography during the late 1960's and early 70's contributed much to the Australian vernacular architectural and town planning debates and the continuing search for national identity; however, it was largely occupied with images of present urbanism, industrialisation and migration issues.

Stacey's Australian vernacular architecture and landscape photographic endeavours were different in that they were centred on the under-represented Australian countryside, its threatened buildings, landscape elements and forgotten lifestyle heritage.

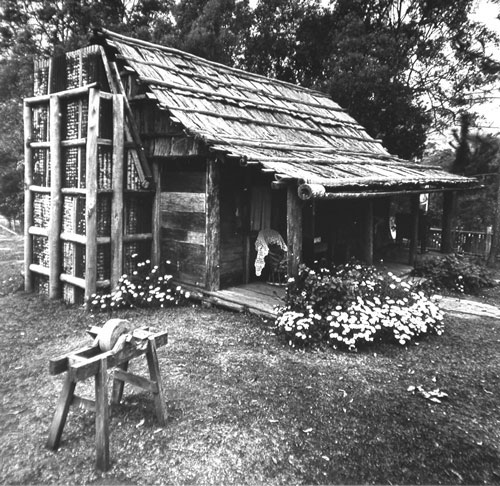

Stacey's pursuit of the vernacular began during 1969 following an introduction between Stacey and a young architect named Phillip Cox by an ABC co-worker Zoron lanjic. In the years that followed, these two enigmatic figures embarked on a pioneering project to survey and document Australian vernacular architecture and its landscape settings that resulted in the publication of numerous books. The first book of this series was Rude Timber Buildings of Australia, a large format book featuring black and white photos of selected timber structures and their environments, with detailed references to their geographical and historical contexts as well as technical information. This representational methodology repeated in many of Stacey's future publications.

The photographs in Rude Timber Buildings of Australia were taken by Wesley Stacey following an elaborate research and selection process carried out by him and his now close friend Phillip Cox. The book was published by London's prestige Thames and Hudson publishing house, utilising Stacey's contacts from his days in London. Together Stacey and Cox travelled through outback New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, mapping and documenting towns, buildings and landscapes from the faded ages of the urban consciousness of Australia. The photos in Rude Timber Buildings of Australia are accompanied by text written by Professor of Architecture and writer John Freeland, whose words lead us through the story of timber and timber buildings to the history of the colonization of Australia, the evolution of its timber and building industry, and the importance of cherishing and preserving this diminishing world:

Published at a time when Australian politics, economics and culture was moving away from its traditional rural image, the publications of Rude Timber Buildings of Australia and the following publications; Building Norfolk Island (1971), The Australian Homestead, (1972), and Historic Towns of Australia (1973) drew much needed attention to the neglected outback cultural and habitation heritage. The architectural theme of the books is strongly linked to their environmental and historical context, and Stacey's photographic focal point henceforth was directed to the landscape as a whole, surpassing architectural interests alone. The landscape photography that came out of his search for new aesthetics and meanings in the Australian outback brought new visual and contextual material that reflected a reality vastly different from the one portrayed by pastoral art only thirty years prior:

The public debate over the preservation of architectural heritage was very successful and played an important role in the creation of The Australian Council of National Trusts established in 1965. Further expansion of heritage awareness, and a diverse network in national planning mechanisms in all levels of government and community, became ingrained in all aspects of Australian life. 'And such exploration of our past has not only have been one of passive enjoyment. It has no doubt, helped immensely in the swell of people working actively to preserve and restore the remains of our historic legacy' (Stacey, 1975, p. 7). Stacey's photographic style and choice of frames in his architectural photographic publications were as distinct as the motivation behind them. The photos in Rude Timber Buildings and the following publications first strike the viewer as particularly dark, and the contrasting structures and landscape compositions are highly charged. Stacey, in referring to these qualities of his photographs, said:

The choice to heighten tonal contrasts by printing his photographs a shade darker than their natural light became a practice that persisted throughout much of his future photography:

The majority of Stacey's pictorial surveys of Australia's townscapes are imbued with rather eerie and sombre feelings because many of the depicted human made elements in the landscapes are either in disrepair, dereliction or ruination. 'There's a fascination frantic in a ruin that's romantic', said Joseph Gandy, and ruins have indeed been one of Stacey's reoccurring motives, disclosing romantic compassion hidden behind the 'as it is' photo-journalistic foundations of his art. The magnificent book Pleasure of Ruins (Roloff, 1964) brings many images and elucidations of the powers that old remains of buildings have on us. Contemplative and nostalgic is Hubert Robert when quoted on the subject:

Applying such choice of subject matter combined with a thoughtful effort to darken the field of vision might vindicate some of Stacey's photography of a melancholic streak. 'Melancholy, the most calamitous affliction of soul and mind, often oppresses men of talent and of genius' wrote Hugo Grotius in the seventeenth century (cited in Antoni, 2003). While Stacey's sinister face proves to be balanced by many portraits of wit and humour, melancholy's dark mental state is also known to have sides of great esteem:

Beside deep psychological effects on the human soul, ruins also contain physical evidence of past lives, events and materiality, the sources archaeologists and historians much rely on in their work. As exclaimed by the writer of Pleasure of Ruins Constantance Babington Smith: 'Today perhaps we consider the ruined building itself more objectively, as the visible effects of History in terms of Decay' (Roloff, 1964, p. 284). Stacey's occupation with the architectural heritage of Australia's rural environment and his working relationship with Philip Cox lasted until 1967 when he left a wealth of remaining photographic resources to be edited and published in the following years. The two enigmatic individuals have since parted ways following misunderstandings and disenchantment. Stacey describes Cox as an international architectural success whose strength and focus is on management of work, contrasting with Stacey's occupation with refining a personal vision of Australia. Stacey has made Thubool his home where, in between travels, he resides in a 'wooden-tent' (In the words of his close friend, Sydney landscaper Murray Cox), secretly nestled in the Casuarinas grove above the rocky bay. In contrast, Philip and Louise Cox utilised the property as a holiday destination, building throughout the years an elaborates: residential complex that includes tennis courts and mowed lawns upon land cleared of the coastal forest. Stacey and Cox have become amicable again in recent years (Stacey, 2003:a).

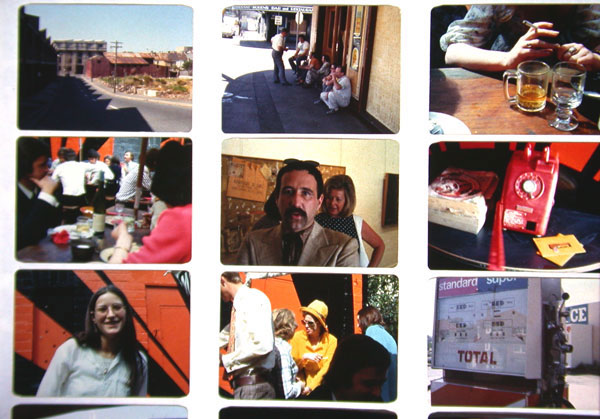

Making Art - Sydney in the 70sWhile he was working on the publication of rural architecture in Rude Timber Buildings of Australia and becoming acquainted with the Australian countryside, Stacey's Sydney environment of the 1970s still offered him a vibrant art community with a dynamic and productive atmosphere with plentiful opportunities. Photography in particular was enjoying growing support from the public, the art establishment, government institutions and joined forces of influential practitioners, all contributing to a bloom for photographic expression. Stacey's personal life and photography was immersed in his Sydney environment and he made many experiments with his camera and photographic processes. In the period between 1970 and 1975 Stacey produced a large and diverse body of work that included his participation in the artist community of the Yellow House and the subsequent 1971 publication of the book Kings Cross Sydney, a modest and delightful narrated pictorial account of Australia's most notorious red light district.

A Personal Look at the CrossThe Kings Cross Sydney book is an historical document and artistic statement in which many photos and entertaining texts tell the colourful story of the Cross. The story is narrated by the 'just out of school' Ellis and Stacey; however, the book's photos and psychological, social and historical insight reveals a depth of vision and a sharp, yet compassionate analytical perception. The Kings Cross Sydney is a book concerned with many aspects of 'place'. The visuals and the words touch upon many current social issues such as the built form, the streetscape, social welfare and inter-neighbourhood relationships, and, of course, many of the more subverted or perverted aspects of humanity evident in the Cross's gutters and back rooms.

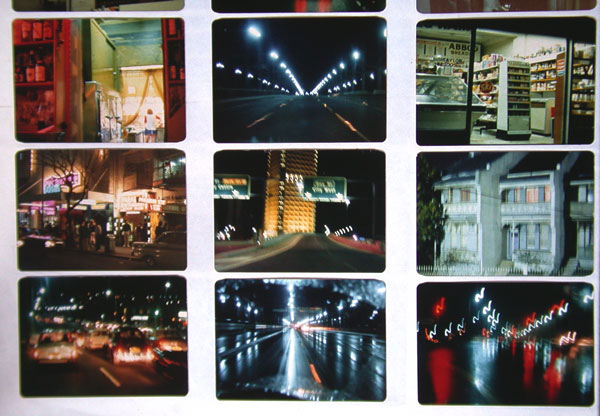

Following this came two exhibitions of photography dedicated to Sydney: The Edge and The Road, both taking place in 1975. The Edge was a celebration of Sydney's seaside living depicting images of Diamond Bay, the Eastern suburb perched on the cliff tops that extended from South Head to Bondi. The Road was a pictorial sequence of the artist's car trips around town, an innovative exhibition celebrated as a significant photographic and artistic achievement, revealing Stacey's interest in the process of production as well as the static image.

The Road also signified recent photographic technological developments as it increasingly permeated popular culture and everyday life. The spontaneity of recording events, places and people made available by the instamatic camera and affordable printing was also redefining the role of the photographer and photography within the arts, blurring the boundaries between the visual and performance arts. All of the above were used by the young and empowered artist to convey a new worldview afforded by technology and personal freedom, lyrically described by Dziga Vertov:

Towards the Self Portrait, The Edge and The Road, like many of Stacey's past and future exhibitions, additionally demonstrated his skills in graphic design and the application of his technical handiwork. The photos featured in The Edge were lined up along the walls of the gallery's room forming a continual sequence with the horizon of the Pacific Ocean being the common unifying element. Towards the Self Portrait presented the spectator with some 354 small images arranged on large panels, creating a playful and colourful stain glass-like effect (Stacey, 2003 c).

The Artist Craftsmen in AustraliaAnother adventure of Stacey into the social realm outside the occupation with the built environment was the research and assemblage of the book The Artist Craftsmen in Australia. Written by Fay Bottrell, photographed by Stacey and published in 1972, The Artist Craftsmen in Australia is a vivid pictorial account of 1970s popular culture in Australia. Looking at it from the perspective of time (thirty one years ago) it strikes the viewer as extremely intriguing, colourful and faithful to the time and culture it documented. The inner-back jacket of the book describes in the same vivid manner the value of the book and its worldwide circulation:

The book The Artist Craftsmen of Australia provides detailed accounts of the arts, tools, materials and workspaces of the forty Australian craftspeople it features, additionally providing a descriptive view of their habitats, lifestyles and creative processes as well as personal insights. Although not specifically relevant to its topic, the presence of the landscapes in many pictures in the book perhaps again is revealing Stacey's enduring view of the surrounding environment as an integral part of living and creating. The book proves an enlightening and entertaining almanac of 1970s trends in garden design as well as a tool to evaluate the changes in the different environment it features when compared with today. The period in which the book was made was distinctive not only in its style but also in the changes that occurred at the time in respect to the craft and arts movement in Australia, as reflected in the evolving understandings and practices of skills and professions; photography being amongst them.

The CraftsAn anthropological view of the crafts presents several aspects of interest to this thesis as it illuminates many social values and living conditions associated with this popular occupation. The crafts traditionally are recognised, similarly to vernacular architecture, as specific to the location and the community that yield the craft. In this locality-defined process of social production goods are exchanged, relationships between market places are defined and cultural, social, political and economical identities are formed. Relevant to this thesis is the nature of home made crafts and arts as subsistence activities of traditional rural communities developed to maintain their economic and social structures in the face of the growing power of industrialized urban centres. The research of crafts then enables anthropologists to define the community by exposing its social economic system. The modern craft movement in Australia during the 1970s also reflects the changes that were taking place in the relationship between rural and urban centres. It also came at a time when competing cheap exports from developing countries and market driven industrialisation were placing pressure on subsistence crafts, pressure that seemed to prove a stimulus for the Australian crafts movement renaissance of the 1960s and 70s. Potters, jewellers, weavers and sculptors, the crafts people and artisans in Stacey's photos, were mostly involved in one-man operations out of their homes in either inner-city suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne or in regional Eastern Australia, homes that are invariably surrounded by greenery and a leafy outlook. Most of the artisans in the book are trained artists, a few are immigrants and there is an even participation by both the sexes. Some of the individuals have since won wide acclaim for their craft. The study of crafts making in Australia and its creative and social processes had only emerged in the late 1980's as Australian craft became increasingly diverse with a high profile both nationally and internationally. The book The Artist Craftsmen in Australia portrays Stacey's foresight, vision and ability to recognize significant features in our society in their formation; and, with his camera, to facilitate the recognition and establishment of emerging trends, values and cultural resilience in its diversity.

Artist or Craftsman? The publication of Stacey's book The Artist Craftsmen in Australia also echoes his interest in the relations between art and craft both in his own work and in broad Australian society. The traditional role of photography as a documentation technique separate from artistic expression can reflect a division in the creative processes of many photographers and artisans of other crafts and disciplines. Stacey was similarly dividing his views of his different photographic achievements according to the motivation, purpose, topics, and the aesthetics of the resulting pictorial presentations. To be an artist conventionally means to produce something new out of existing conditions and materials, be it a new image or meaning (Berger, 1969, pp. 10-11), while photographic illustrations traditionally sought to accurately depict existing conditions for scientific recordings. The distinction between arts and the applied crafts is also a matter of prevailing popular attitudes and conventions created by political and social ideologies influencing contemporary Australia through its education system, media and other political instruments. This attitude in Australia was consequent of the long-established nation-building ethos where practical skills were valued most and art making considered a trivial accomplishment, a skill of no consequence (Duggan, 2001, p. 86). During the 1940s Australian artists were starting to question the mould of the artist and its view as a designer of consequential production and useful objects, yet the choice to produce art continued to be an act of unconformity, antagonistic to the customary Australian frontier attitude of pragmatism. While the art/craft debate predominantly relied on text-driven fine art theories and art history upon their traditional hierarchical values, by the 1990s this approach was no longer sufficient as expressed by Nola Anderson in the magazine Craft Realities:

Stacey, like many artists-craftsmen, was at times reluctant to call his photographic work 'art', and much of his landscape photography he later assigned to a hybrid mode of expression, fusing the traditional landscape picture making with the school of topographic art of the great explorations now replaced by photography. Stacey's own perplexity and semantic experimentation in this matter coincided with the new photographic term 'New Topographies' that was coined in the USA during the 1970's. Describing that same synthesis between science and the arts, New Topographies was becoming a popular international photographic genus amongst nature photographers to convey environmental ethics and human morality (Stephenson in French, (Ed.). 1999, p. 271). The increasing preoccupation with crafting documentation however was not exclusive, and throughout the years Stacey continued to see art as an important motivation, goal and means of expression: of himself, and of his view of the world. With that, he was drawing on his own interpretations and intuition rather than Stacey was in-charge of, not only the photography, but also the design, graphic layout and production of The Artist Craftsmen in Australia.

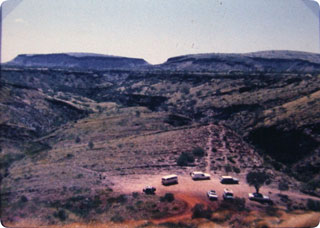

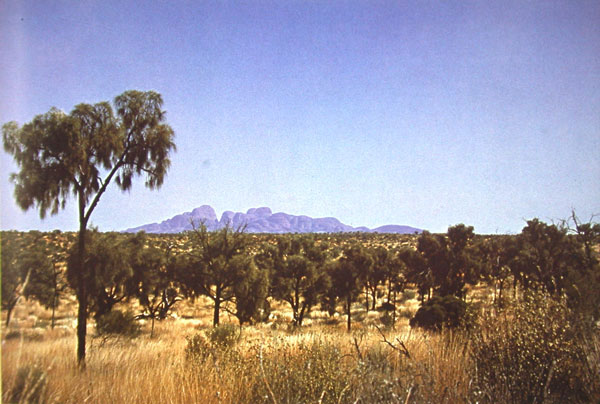

Travelling AustraliaStacey continued to collaborate on his exploration and exposure of cultural and historical elements of Australia's architecture and landscape since his projects with Philip Cox. The obvious need to get out there and travel the land in pursuit of subjects of relevance saw Stacey exploring Australia in ever increasing circles. The early journeys of Stacey include a 1971 epic journey following the footsteps of explorers Wills and Burke with friends including Bill King (of Kings Tours) and photographer Rennie Ellis, and a 1973 pilgrimage to Uluru together with a group of artists including Tim Storrier, Grant Mudford and Melanie Le Guay. Stacey's explorations of the interior of Australia were part of the earliest movement of popular travelling, and photographing, that particular part of the Australian continent. Aided by fast-developing transport routes, this social and cultural movement was preceded with an early 1920s official-national call to turn the barren land into productivity, the establishment of Australian anthropology as an official, academic discipline, and a growing tourism industry. Not until the late 1920s did any Australian artists tackle the arid interior, and even the painters of the 1950s showed their occupation with the interior through the veil of nostalgia and apprehension and not of explorative spirit. Photography therefore preceded other modes of representing the 'centre', and through its archival and serial qualities, photography was mapping the new terrain in a manner addressed as impartial and objective began unifying the region and rendering it comprehensible (Duggan, 2001, pp. 200-203). By 1974 Stacey's work and lifestyle was engrossed with the countryside of Australia as opposed to his native city environment. Eleanor Williams, native of the Isle of Wight in the English Channel, had entered his life and having shared a passion for photography and wilderness, they planed their future adventures; 'When Eleanor and I were in love in Sydney (73/4), we'd eat at La Rustica in Leichhardt - and make plans for going bush. Love, wine and ideas flowed... from where?' (Stacey, 2003 :b). Perhaps in the quest of answering that question, the years of 1974-5 saw Stacey and Williams embarking on extensive travels throughout much of Australia, primarily photographing natural formations. Their book,Timeless Gardens,was published in 1977 and it was clearly an attempt to survey Australian natural environments, portraying not only its uniqueness but also, of importance, its diversity. Timeless Gardens was remarkably different from the vernacular architecture and constructed landscapes Stacey had so far encountered and focused upon in Australia: social history remained behind him and ahead was Australia primordial and sublime:

Timeless Gardens begins with a tribute to the undisturbed natural environment as the source of all of humanity's actions and meaning. The writer then highlights how humanity has become aware and, through the process of alienation and alteration, becomes a part of this ideal natural garden: 'These natural, timeless gardens are the well-springs of inspiration the poets speak of and the territory they familiarize us with is real' (Williams and Stacey, 1977, p. 7). Like the rest of the text in the book, the name of the writer of the introductory text, Kamikaze McNoff, is found only in the small print of the publication data and the writings have neither title nor date. The first picture appears after the tribute: it is the image of earth as seen from space; in its centre rests Australia, shrouded in a misty veil of white clouds.

This photo, with no title or credits, is followed by a fifteen-page poem: nameless and unsigned. Timeless Gardens, while plainly a photographic document by its content, reveals through its text as having profound philosophical existential motifs: 'So while this appears to be a book about timeless gardens, it is actually nothing cunningly disguised, as indeed are the gardens themselves. Nothing is as it appears to be. It is. The it that isn't' (Williams and Stacey, 1977 p. 9). These words prepare the reader for what Stacey and Williams then tell us through their photographs: there is a perfect world of infinite beauty, the world within. This inner world, however, has an outward expression as infinitely beautiful and timeless: the world of nature, the bridge over duality. The second photo in the book is as symbolic as the first, featuring the sacred, and geographical heart of Australia: Uluru and Katajuta. From the red centre we are then taken on a journey through different regions of Australia from Tasmania to far north Queensland, from South Australia to the Kimberley. The photos, large format colour plates, all feature natural forms of the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms on land and underwater. The only few photos disclosing the presence of humans in this land are two photos of aboriginal rock carvings from Gallery Hill, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. None of the photos have been individually titled: they are compiled according to regional location where each environment is photographed in vista and in details, accompanied by a map pointing to its place on the continent, its elevation, the time when the photos were taken, and a poetic clue to its formation. The sparing use of text in Timeless Gardens is perhaps symbolic of the growing detachment of Stacey and Williams from Sydney upon its art community. This was a professional trend that was later recognised as part of the evolving and diversifying photographic discourse:

Text and its absence can also point to the act of appropriation of the picture within a subscribed world vievv by enforcing verbal authority upon the image: 'It is hard to define exactly how the words have changed the image but undoubtedly they have. The image now illustrates the sentence' (Berger, 1972, p. 28). In emitting textual information beside the photos, Stacey and Williams have perhaps chosen to covertly enforce their own heart-felt perception of the natural world they photographed as innocent and detached from the encroachment of politics and even that of human intellect. 'The photograph, under the influence of the text (or caption) expresses not simply the fact which it shows, but also the social tendency expressed by the fact, then it is already, in effect, a photomontage' (Duggan, ed., 2001, p. 202). The occupation with details of natural elements as opposed to cultural landscapes might also reflect a political and ideological shift in Stacey's worldview, furthering him away from the mainstream Australian national conservatism towards an anarchic attitude defying authority and social control. This statement refers to the traditional depiction of overblown nature in a theatrical and exaggerated manner by conservatives and ultra-national parties aiming to create a myth of stability and grandeur rather then to inform or instruct further understandings of present conditions (Duggan, 2001, p .17). Despite its pioneering intent and mammoth scope, Timeless Gardens failed to reach the broad public and won only little professional recognition. Stacey attributes the shortcomings of the book to mismanagement and technical inadequacies exemplified by the choice to print the book in Singapore where remote supervision failed to ensure good quality (Stacey, 2003 b).

>>>>> Chapter Three Home-Page / Intro & Acknowledgements / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / conclusion / illustrations / references

|

• photo-web • photography • australia • asia pacific • landscape • heritage •

• exhibitions • news • portraiture • biographies • urban • city • views • articles • • portfolios • history •

• contemporary • links • research • international • art • Paul Costigan • Gael Newton •