|

|

Home-Page / Intro & Acknowledgements / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / conclusion / illustrations / references

Landscape of Virtue:The Life and Work of Photographer Wesley Stacey – Ziv Cohen 2003

Chapter one:Landscape photography, an historical perspective

The invention of the Daguerreotype in the first half of the nineteenth century had greatly influenced the way in which humanity views itself and the world around it. This new mode of visual communication not only transformed perceptions and public opinion but also played a significant role in the broad-scale reshaping of the face of the earth in the hands of modern man. The following chapter aims to shed light on the history and evolution of photography together with some of its philosophical and practical aspects. A particular focus on landscape photography will emphasise the relevance of this chapter to the specific topic of this thesis. Coming into the world at a time when picture making was the domain of the handmade arts, and nature was considered the manifestation of God, the very technique of photography challenged both the notion of what is art, together with the perceived relationship between man, landscape and God. Some welcomed the intervention of photography in the conventions of the time. Oliver Holmes argued:

However, others perceived its conception as a threat. Charles Baudelaire argues:

The mechanical characteristic of photography in its early days was thought to be a precise, accurate and faithful rendition of the objects it captured and represented. Well into the late nineteenth century, the expanding trade of photography in the fields of portraiture, architecture and landscape imagery was persistently viewed as a passive recording of pre-existing sights belonging to the realm of the unimaginative and the practical, differing from traditional handmade picture making that was viewed as imaginative, creative, evocative and spiritual. This common view, however, did not release photography from the aesthetic and moral conventions of the audience of the time; early landscape photography was dominated by the existing artistic expression that dictated much of the subject matter and style of representation. The inevitable result was photographic images which were mainly romantic and picturesque, depicting scenery not unlike those painted by the landscape painters of the period. The technological development of photography echoed the transformation of popular cultural and social structures induced by the industrialisation of Europe and America in the nineteenth century. While the photography of the early period was confined to a limited market due to the lack of mass printing technology, the later development of photographic ink printing saw the creation of large market potential. By the late 1870s, publishing houses and distribution networks of photographic products, and landscape photography in particular, were spanning across the United States and Europe, selling artistic and promotional items to the wider public. Photography had been fast establishing itself as a new and distinct economic market and field of activity, a medium that could not be served by other picture making techniques. The advance of photography in the two realms, that of the fine arts and that of the commercial media, can be seen as two parallel lines that are closely linked by a shared technological evolution, as well as ever-evolving public opinion and trends. Landscape photography was no exception; its rapid progression as an economic, political and aesthetic asset was increasingly popularised thanks to the development of the rail and motorcar, the growing travel industry and the relinquishment of photography from the hands of the privileged upper class to the wider public due to a growing middle-class and the popular press media. (Snyder, 1994; in Mitchell, 1994, pp. 175-179) As the discipline of photography was the child of technological progress, so too was much of its content becoming due to the emergence of purposely-commissioned photography documenting the intense industrialisation and infrastructure developments gripping much of the American continents. Here we can see the beginning of not only large-scale commercialism, but also, arguably, a move away from an accurate and objective pictorial depiction to an image manipulated by a subjective purpose that can be shaped by the choice of position, frame and tonal manipulations. Exemplifying this is the monumental photographic documentation of the railway and mining industries rapidly developing in western USA, as seen in the work of photographer Carleton Watkins in the late 1860s. Devoted to the idea of progress, Watkins manages to aestheticise the scene of large-scale human intervention in the landscape, and through careful selection of framing and tonal manipulations he created pictures of visual pleasure otherwise not found in the scene itself. Watkins' work won wide public acclaim as it echoed the expectations of the audience of the time.

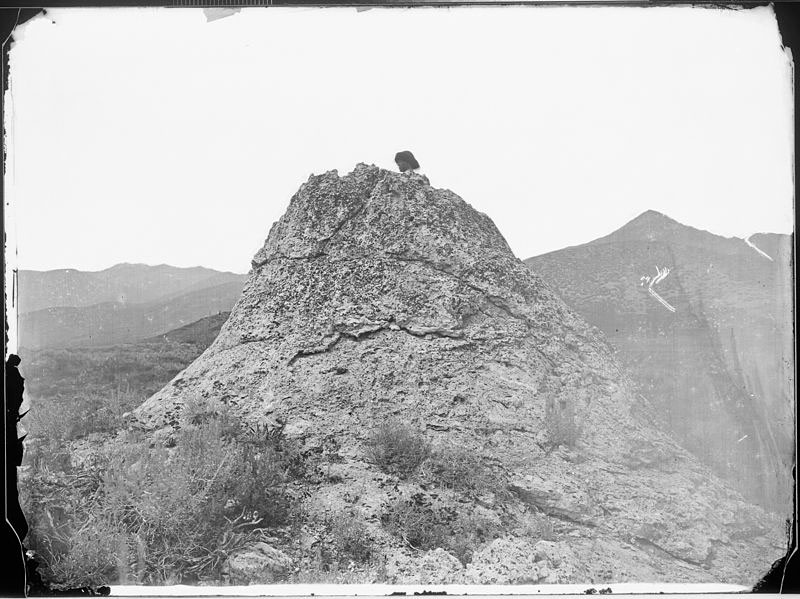

Just as Watkins' photography embodied a certain common world-view of the times, other landscape photographers were using this increasingly malleable representation form to deliver a different attitude and perception of the land that they had explored. Timothy H. O' Sullivan might serve as an example of such different vision brought from the first civilian scientific expeditions to the interior of the USA during the years before and after the turn of the nineteenth/ twentieth centuries. It is worth noting that while photography at this stage was held by the wider public as an instrument of precise documentation, the scientific community on the contrary had rejected it as a means of scientific recording. O'Sullivan's role in this new form of expedition was not to provide scientifically accurate pictures for which a band of topographical draftsmen was assigned; rather, he was to produce generally descriptive photographs and to "give a sense of the area' in the words of the chief in charge (King, 1871; cited in Mitchell, 1994, p. 196). O'Sullivan's photography stands in sharp contrast to Watkins' photographs of uplifting humanised landscapes: his representation of the newly discovered west was described by Joel Snyder as 'an awed stare into a landscape that is unmarked, unmeasured and wild, a place in which man is not yet, and not without an immense future effort - the measure of all things' (Snyder J. in Mitchell 1994 p. 196). By confronting the viewer with such untamed nature and depicting the inaccessible and sometimes grotesque qualities of the landscape, O'Sullivan was answering not only to what might be the call of his own heartfelt response to the landscape but also to the purpose and task for which he was hired. This land he was photographing was viewed by the explorers that ventured there as 'the last place on earth upon which god had stood... a testimony not only of God's glory but that of the conquering man' (Snyder; 1994; in Mitchell, 1994, p. 198).

The increasing use of photography as a means to convey a message had in turn informed and enabled an increasingly wide population to critically evaluate the content and concept of the information they received. Photography was fast becoming not only a tool to look at the apparent world, but also as a tool to reveal hidden attitudes, underlying beliefs and hidden agendas. Landscape photography was similarly used to further analyse the broad context of its subject and served to formulate social and political commentary, whereby bringing it to the fold of the discipline of art history. An example of the use of landscape photography in such light can again be manifested in the following critique of the work of Watkins:

The interpretation of landscape photography as a reflection of both personal world view and social and political ideology is illustrated by the evaluation of O'Sullivan's work some 130 years after its days:

The use of photography to evaluate and demonstrate past, present and future social trends had since been widely used by all participants of the social mechanism, from art historians to politicians, entrepreneurs and laymen; all utilised the power of photography to project their own, and thereby influence others, opinions and views. Today's multi-layered approach to discerning photography's meanings is well expressed by Bill Nicolas's writings:

The field of landscape photography has an obvious power over the understanding and interaction of society with the natural world together with the fulfilment of a more personal psychological need to reflect one's origin and place in the world. Popular demand by an increasingly urban population to experience nature had fuelled an increasing production of landscape photography assisted by a growing popular tradition of travelling to national parks and rural environments, the 'outdoors' of urbanity. This in turn played part in the rise of the popular environmental protection and nature conservation movement. It is noted that concerns that emerged over the alteration of nature in early days of the industrialised era often stemmed from religious, romantic and aesthetic sentiments, disturbed by broad scale desecration of nature, God's creation. Yet, from the 1980s, politically driven environmentalism was emerging fuelled by the view of the natural landscape as an endangered economic resource together with the recognition of open public spaces as having a valuable cultural, recreational and psychological significance. Landscape photography was used extensively to deliver images of nature's beauty as well as images of environmental degradation, therefore becoming one of the environmental and conservation movement's best ally. An early example of the power of landscape photography as propaganda harnessed by conservationists is evident in the creation of Sierra Nevada's Kings Canyon National Park, a direct subsequence of the viewings of Ansel Adams' photos of the region by the president of the United States of America (Gaskins, 1978, p. 7). Along side the preoccupation with the natural and rural world, the modern era of the twentieth century was seeing the urban landscape featured in landscape photography in an increasing volume with a diverse range of styles and meanings. Popular culture of modern times, as reflected in landscape photography, was grappling not only with a growing detachment from the natural and rural landscape, but also with new human conditions set by unprecedented population density, technological changes and an evolving world view. Here again, landscape photography contributed to creating new aesthetics and market discovered sights, and also, critiques of the downside of the urban condition such as alienation, pollution and resource distribution. The different works of landscape photography might be interpreted and used in many ways and for different reasons, yet its accumulative impact has undoubtedly heightened and enriched the human experience of the world and itself. Be it an explicit or implicit idea about nature, art, religion or the technicalities of picture making, the choices and actions that yield that photo and the interpretation of it are all heavily influenced by ideology. This ideology can be that of the photographer, the viewer or the agent that placed them in a given context. Exploring and understanding ideologies embedded in the picture can reveal the intriguing reasons behind the composition of culture and of nature, of matter, spirit and of life.

Photography and landscape photography, an Australian perspectiveUnlike the American experience, photography in Australia did not participate in the early major explorations of the continent. Even after its arrival in 1841, the pioneering expeditions to the harsh interior could not afford the assignment of a dedicated professional photographer, and at best they were illustrated in the classical means of hand drawn illustrations and engravings (Newton, 1988, p. 45). Photography though was rapidly adopted by the growing colony and used extensively to document, communicate and later entertain the civil and scientific community in its different localities. By the mid nineteenth century, Australia had passed its days as a penal colony and its population comprised of many free settlers, as well as an emerging middle and upper class of well to do people who could afford the expensive technology and who also possessed an awareness of the benefits of documentation for present and future generations. The ethos of colonisation and civilisation of the last discovered continent saw a growing expression in photographic documentation through images of new expanding infrastructure, civic buildings and primary industries. Amongst the first subjects to be captured by photographers were farms and farm machineries as well as ships and their crew (Ennis and Crombie, 1998, p. 6).

Parallel to popular culture, photography was quenching the thirst of the scientific community in Australia and abroad by delivering images of the lay of the land, its flora and fauna and its native population. Geological surveys and documentations in particular were utilising the tools of photography. Publications of images from the antipodes were widely published in Australian and English scientific and popular press, anticipating the emergence of photojournalism in the early twentieth century. The unfamiliar landscape of Australia with its natural formation and newly discovered plants and animals was an obvious source of interest in the 'old world', and landscape photography fast became an export commodity (Newton, 1988, p. 46). Later advances in photographic technology, in addition to the growth of the colony, saw the appearance of commercially produced 'views': merchandised items sold to locals and visitors by the page or in albums. Together with portraits of people, properties and images of public infrastructures, images of naturalistic scenery and landscape photographs were popular, especially those closer to the developing centres of Tasmania, Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australia. As in Europe and America, following in the footsteps of the English tradition, the use of photography in portraiture was increasingly popular and many photographers ventured beyond the main towns offering the rural inhabitants the chance to purchase permanent images of themselves, their families and homes. Some of these photographs were later reprinted and sold, creating a national identity closely linked to the lifestyle and imagery of the Australian bush. Australia's growing national identity was closely linked to the bush, rural settings and farming and remained this way well into the mid-twentieth century. In addition, a significant contribution to photography was made by the more civilised city dwellers; they gradually began to view photography as an art form to be exhibited and marketed nationally by a growing number of amateur practitioners of the wealthy upper class. Australia's first female photographer, Louisa Elizabeth How, was amongst those first exhibiting photographers in Sydney during the late 1850's. Landscape scenery, social events and cultural portraiture were favourable subjects (Ennis and Crombie, 1988, pp. 12-16). The discovery of Australia's goldfields transformed many aspects of life in the remote colony, one of which was the demand for newsletters which started to circulate amongst the diggers and their relatives overseas as soon as 1850. It was not until the 1890s, however, that photography became an economical option soon to replace illustrations by painters and sketchers, and news of gold strikes were soon replaced by other current affairs giving birth to modern media and photojournalism. The hanging of the Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne in 1880 (printed c. 1910-40) is considered to be the first media event in Australia with photographers and artists invited by the police to cover the event.

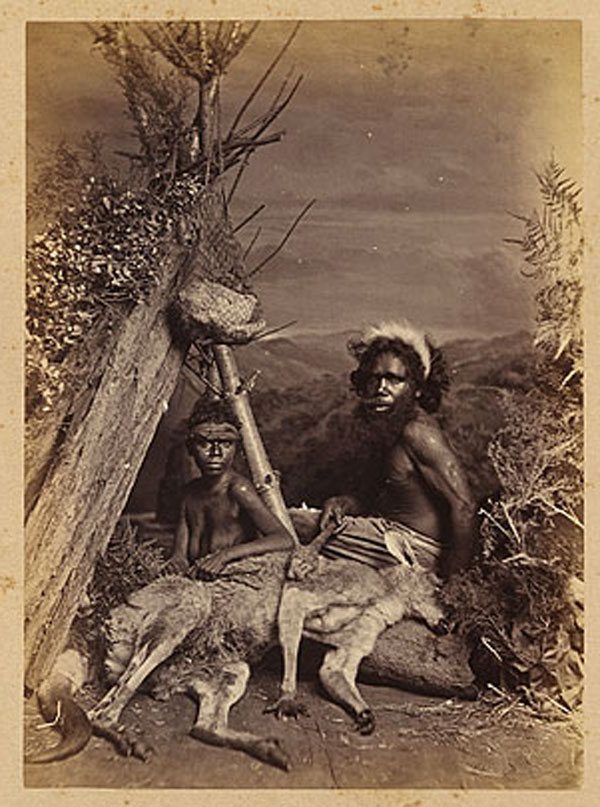

The fortune made by the discovery of gold also saw the financing of better and larger photographic productions culminating in the Holtermann Panorama, a 978 centimetre image of Sydney. The image, comprising of twenty three albumen silver plates was taken by Bernard Otto Holtermann to celebrate his good fortune in finding the world's biggest nugget of reef gold at Hill End in October 1872. The panoramic photo was the jewel in the crown of a travelling exhibition touring the world during the 1870s, together with Australian primary produce, mineral samples and other photographs (Ennis and Crombie, 1988, p. 18-20). The first half of the early twentieth century continued to occupy photography with images of the emerging nation affairs and the continuing search for national symbolism. The 1920s signalled the beginning of the movement of modernism influencing the arts and also witnessed photography releasing itself from the confinement of the picturesque and documentary to the realm of creative and manipulative expressions. The Australian field of landscape photography however was still extensively used to express the growing national identity, still an image closely linked to outdoor scenery and related activities. Gum trees, surfing, picnicking, industrial and urban expansion and infrastructure developments continued to feature prominently, but its form was changing with the times. New vocabulary of expression produced photographic images of clear forms in bold compositions, and an unconventional choice of framing was used to explore natural, mechanical and figurative forms. The advent of mass media and broadcasting with its powers of photojournalism and commercial advertising saw the increasingly popular face of photography dominated by consumer advertising, fashion, entertainment and lifestyle (Newton, 1988, p. 28). The aftermath of the two World Wars had a sobering effect on much of the world, and Australian photography also reflected a return to a somewhat fundamental humanistic worldview where the ordinary and realistic became re-evaluated and rediscovered. Social and political events and issues were prominently featured in photography, documenting the re-emergence of the workers movement, emigration and demographic issues, feminism and racial awareness. Socio-political issues and personal liberties kept dominating photography and the arts, enforced by the Vietnam War and the coming of age of the Baby Boomer generation. The age of international travel and mass communication had opened up Australia to the concept of cultural diversity and counter culture with the realisation of Australia's own indigenous and white cultural values and heritage. Distinct Australian imagery was solidifying and expanding in variety and form to include colonial architecture, geographic landmarks and icons of popular culture. Together with a growing awareness of the psychological and economical value of these icons, photography's power emerged through its showcasing of the degradation and destruction of cultural and natural resources, fuelling the rise of a popular heritage and nature conservation movement beginning in the 1970s. The artistic expression of modernism in Australia was depicted by images returning to photorealism and documentary-style subject matter revolving around the personal experience in the urban environment, the common place, and the relationships between them all (Newton, 1988, pp.139-142). The cross fertilisation between photography and the other fields of contemporary arts was most evident in the 1980s when a new generation of photographers emerged from the nation's art institutions as trained artists. Photography had become occupied with its own mode and style of representation as an important aspect of the delivery of the subject and the position of the photographer and viewer in their relation to the picture. Manipulation of prints through interventions in the developing stage, in addition to photographic installations comprising of elements outside the picture itself, became a vehicle with which artists challenged the photorealism of their predecessors. Photography was increasingly becoming an independent branch of the visual arts and many Australian cities saw the development of artist-run exhibition spaces, galleries and media dedicated to the promotion and exposition of this media alone. The 1980s also saw many marginal groups of mainstream society becoming an accepted and legitimate part of the cultural discourse with feminism, ethnicity, the gay movement and multiculturalism keeping up with the demographic, social and cultural changes that were evolving in Australia during the past twenty years. This process was clearly aided and documented by photography (Newton, 1988, pp. 154-159). Australian photography and Aboriginal AustraliaAustralian Aboriginals featured in Australian photography within the many fields attended by it since the early days of its arrival: science, portraiture, official and commercial media, personal curiosity and later religion, military, politics and police (Dewdney, 1994. p. 21). All saw to the production of many thousands of photographs of native Australians already taken by the end of the nineteenth century. The earliest photos of Australian natives were taken in 1846 at locations of close proximity to the first settlements of Tasmania, New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia; images of Victoria's Yarra Yarra tribe were published in a book in Edinburgh as early as 1848. The lively trade in Aboriginal photography was stimulated by the thirst for the exotic in Europe during the late nineteenth century, but it was short lived and superseded by the more popular form of landscape views (Newton, 1988, p. 12). Many of the early images of Austrahan Aboriginals taken by the European colonists were designed to satisfy market and cultural expectations of the European community, and their subjects were often made to pose in contrived studio settings. Together with the required scientific documentations, many white Austrahans believed the Austrahan Aboriginals were a dying race and were keen to capture their image before they disappeared (Ennis and Crombie, 1988, p. 10). By today's standards, those photos might appear to represent acts of invasion and disrespect (Dewdney, 1994, p. 27).

The end of the nineteenth century saw the establishment of Christian missions in many parts of the continent which assisted the arrival of photographers to the Aboriginal communities of the interior (Newton 1988 p. 50). Not until the middle of the twentieth century did Australian Aboriginals start to appear in photographs as subjects independent of the objectives and values of the white photographer and his/her European social backgrounds. The 1970s brought Australian Aboriginals back into the public eye, but this time not only as individuals with their own identity but also with an important reflection on the history of white Australia and its grave influences on the pre-existing population. Together with assisting the important process of acceptance and reconciliation of black and white cultures in Australia by the use of historical photographs in media and political campaigns, photography played a major role in the reconstruction of indigenous Australia and its cultural revival. This was achieved by providing knowledge of past customs and events otherwise lost, and by capturing and profusely delivering images of newly created Australian Aboriginal visual and performing arts to an appreciative worldwide audience. The Aboriginal rights movement was closely linked to the emerging environmental movement as Aboriginal habitats, together with their traditional lifestyles in rural Australia, became increasingly affected by developments such as mining. As the landscape of Australia became the battleground for the two seemingly independent social issues of Aboriginal affairs and nature conservation, landscape photography became increasingly visible in the Australian press, politics, and artistic and popular culture (Ennis and Crombie, 1988, p. 48).

>>>>> Chapter Two Home-Page / Intro & Acknowledgements / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / conclusion / illustrations / references |

• photo-web • photography • australia • asia pacific • landscape • heritage •

• exhibitions • news • portraiture • biographies • urban • city • views • articles • • portfolios • history •

• contemporary • links • research • international • art • Paul Costigan • Gael Newton •