On The Edge: Australian photographers of the Seventies

The Soft Spread of Time

Gael Newton 1995

Main catalogue essay for the exhibition of Australian 1970s photography at the San Diego Museum of Art

In Australia, my generation and that of the majority of the artists in the Philip Morris collection is tagged the “post-war baby boomers.” We grew up in one of the most affluent periods in Australian history, an era in which the young enjoyed greater economic, social and intellectual independence than their parents and grandparents had known — or so the legend goes.

Our pedigrees as products of the so-called “swinging sixties” and the “counter-culture,” as manifested in Australia, are rarely as pure as the mythologies of the radicalism of the era might suggest. One radical change in the seventies took the form of an enthusiasm for photography as an art.

As one of Australia’s first curators of photography, I witnessed the convergence of photographic genres to form what became the new photography movement of the 1970s. Most institutional and corporate support for photography as art in Australia dates only from the early seventies and the Philip Morris collection is regarded as a time capsule for the distinctive photography of that decade.

The collection was selected from exhibitions and acquired between 1976 and 1988, and most of the prints were made in the seventies. A selection of works from the 1930s to the 1960s by the established professional photographers from these earlier decades also forms part of the collection. All the works are now “dated” by concerns, styles, and values which started to be challenged and modified as early as 1980.

The personal manifestoes of two Australian photographers working in the seventies sound out some of the changing perceptions of the time about the relation between photography, self, and society:

The first twenty years of my photographic life were devoted to working in the idiom of Life magazine. Now I want to change, to take a fresh viewpoint, to loosen up. Life magazine taught me to shoot for the climactic moment, now I want to examine the soft spread of time ... I think that as photographers we have a responsibility to look at the ordinary areas of our existence and show just how extraordinary they can be. Photography can be a powerful aid in the future understanding and appreciation of our visual world.1

David Moore (aged 47)

For me photography has always been a pure art form. I have chosen to teach so as to avoid being involved in commercial photography. I am an artist whose tool of expression is the camera. My main interest in photographic art, as in living, is giving; (learning and sharing). This society is sick and I must help to change it.2

Carol Jerrems (aged 25)

By the mid-seventies David Moore was long established as Australia’s most eloquent photojournalist. Carol Jerrems stood in the front line of the new generation of art photographers. His tone is mellow and liberated; hers is militant. Yet for both, photography in the 1970s was fresh and powerful. What lay behind their views as practitioners was a radically elevated public perception of the value and potential of their medium and this helped fuel an unprecedented level of photographic activity within the visual arts in Australia.

In a photograph of Carol Jerrems taken around 1975, [Fig. 1 ], she wears an insignia of her generation — a lapel badge which is inscribed: ‘You’re among equals.” It is a statement /challenge open to many readings beyond the feminism to be expected from a young woman artist in the seventies. It could also apply to the quest at this time to expand and redefine the traditional hierarchies in the visual arts.

Despite the millions of photographs made since the debut of the medium in 1839, to young photographers in the 1970s it seemed that photography was somehow “their” medium. They were aided by the availability of sophisticated, but simple-to-use single lens reflex cameras which promised easy access and spontaneity in capturing the feel of the times and their own personal take on culture.

Photography fitted easily into a free-ranging lifestyle and the increasingly popular treks by young travellers through Asia and the Middle East. A heightened consciousness of the ways in which photography could render the objective world subjectively probably also owed a certain debt to the collected wisdom arising from drug experimentation among the young. Photography was not new in the seventies nor was it the exclusive domain of any age group. The medium also had its past masters and devotees of the process as a pure art form, even if its history was never linked to that of the mainstream arts.

Neither was the energy among contemporary photographers exclusive to the very young.

Older photographers like David Moore also responded to the new climate of possibilities for their work in the seventies. Not all so-new either were the personal statements in the photography publications of the early seventies. Jerrems’s words could have fit the agenda of many past documentary photographers with a social mission, and in Moore’s views there is an echo of the “new photography” of the thirties, when the first modern 35mm cameras unleashed a flood of new angle views on the everyday world.

What then was new about the “new photography” of the seventies apart from its new status with official cultural organizations? Why did the younger artists feel so comfortable with the medium?

Perhaps the post-war generations were simply much more familiar with and dependent on photomedia than any previous era. They had been raised on a glorious smorgasbord of images from movies, picture magazines and television (introduced to Australia in 1956; color television came in 1975). Those with a taste for “arty” movies would also have found in Antonioni’s pseudo-thriller Blow up (1966) a fashion photographer as hero. This film even suggested the medium itself as the key to understanding the gap between perception and reality.

Pop art in the sixties also promoted the idea that the contemporary commercial culture was a fitting subject for art.Most pop art was heavily dependent on a strange alliance between graphic art flatness and pattern and photographic tone and composition. |

|

|

The post-war generation’s familiarity with the medium may also have helped breed the contempt for commercial professional photography evident in many of the published statements by Jerrems and other younger photographers of the seventies. Even the more respected genre of photojournalism was no longer the goal for young photographers as it had been for David Moore and many of his contemporaries in the fifties. There were skepticism about the social efficacy of old style “concerned” or humanist documentary photography and critiques of the philosophy behind it.

The ever-growing industry of rock music also articulated a rejection of the values of the older generation, further defining “youth” as a separate global class and culture. These trends would be even more marked in the generation that grew up in the seventies. From the mid-sixties the traditional fine arts, and abstract painting in particular, were seen as exhausted, and many students turned instead to the photography courses making their first appearance in art schools at this time.

Other young people who felt the call to photography simply began to work in isolation. From their ranks came the several hundred dedicated art photographers of the seventies. It seemed in the early seventies that young art photographers were springing fully formed out of the suburban woodwork. The dark mood of many of their works may include an afterglow of the unrest of the previous ten years from 1965, when a National Service Act was introduced specifically for the Vietnam War, mixed with continued protests against “The Bomb,” and debates over social and gender inequalities.

Photographer Wesley Stacey has spoken about his relief that “It was over!” and the burst of creativity which followed the end of the war.3

The “photoboom,” as the phenomenal growth of interest in photography in Australia in the seventies is sometimes known, was not unique. Similar patterns of change in practice and official policy, as well as marketplace activity in collecting prints as art, showed up in the affluent middle classes of most Western countries in the sixties and seventies. Precedents and leadership in Australia came from centers overseas such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which was also active in touring exhibitions in Australia. The spectacular growth of high-quality photographic publishing in America and Europe fanned and sustained the international following for photography as art.

Australian photographers looked to European and American photographers. Few of their biographies or commentaries on the works propose any past Australian photographers as models. As James Mollison commented in the Australian Photographers: The Philip Morris Collection catalogue in 1979: “The aware art lover in this country in the early 70s knew of photography through the work of perhaps a dozen people, through their infrequent one-man shows, and the less frequent publications and museum surveys of those days.”

Despite an emphasis on young and emerging artists, David Moore was not the only artist with an established career to be considered part of the new trends in photography. The most prominent men in professional photography in Sydney and Melbourne were acknowledged and included in the early exhibitions and surveys. The images chosen were from their personal work, or, if shot on assignment like the Henry Talbot advertisement for the Australian Wool Board, [Fig. 2], were those with either a documentary or a more poetic character.

The elect among the older professional photographers were all men. Women in professional photography after the Second World War were virtually invisible.

The early seventies marked a significant change with a considerable number of young women happily choosing photography and persevering with it even when constantly confronted with various forms of prejudice. Most did not choose the kind of roving street photography which appealed to the males. Very few worked with landscape. The women often chose to work in situations which permitted an intimacy and interaction with the subject, as did many of the men.

Some women photographers used photography to develop the tenet that “the personal is political” and some focused on issues such as the care of the young, the old, and the disadvantaged or simply those eclipsed in a consumer/industrial society.

Sandy Edwards used the popular format of sequenced images in her commission for the CSR Prymont Refinery Centenary Photography Project. Her subject, repetitive strain injury among women (often migrants) on the conveyer belt lines and her title, Sugar in the morning, sugar in the evening, (see page 35), suggests links to slave songs.

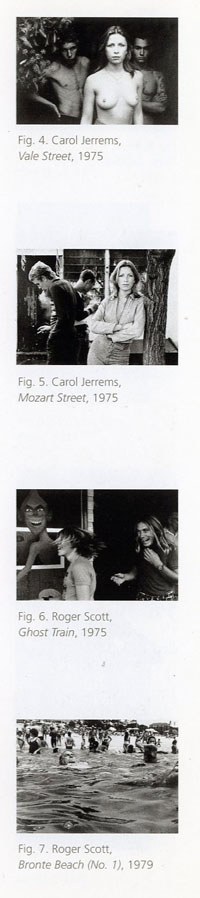

The choice of print process could also be given a political dimension, and gender and genres could be linked to explore new perceptions. Micky Allan was influential in her use of hand-colouring as a means of creating effects integral to the image and not possible in black and white or color papers.

In Yooralla at twenty past three, [Fig. 3], a mother collects her child from a school for the disabled. The reworking of the images in the series with pretty pencil and watercolor, as well as surface markings, makes an ironic contrast with the drabness of the original environment and the invisibility of society’s female care givers.

Something of the same spirit of irreverence for the pure print can be seen in Christine Godden’s later work from 1979 in which she used the bottom line of amateur cameras, a miniature 110, to make a series of images of sunsets (see page 41) around Sydney Harbor and her home in Paddington. Every imperfection on the small negatives was then cheerfully magnified in large color prints specially made to exaggerate the grain. The pictures depart from the fine sensuous line between formalism and feminist concerns which had marked her early work.

Few photographers specialized in color prints before technical improvements in resolution and stability, for instance with cibachrome papers in the late seventies. Very few combined insight and skill in color work and those that did struggled to make their images speak beyond an association with commercial imagery and the travelogue. |

|

|

For all their numerical strength in art schools women constituted only 25% of the Philip Morris collection — a similar proportion to that found in museum collections of the period. This was somewhat counterbalanced by the recognition given to Carol Jerrems. Her image Vale Street, [Fig. 4], was published many times and became an icon of the period. It is one of a number of images of urban teenagers taken around 1975.

The scene was, we now know, staged for the camera. A number of reviewers assumed that it represented some free-love community or teenage orgiasts and at first did not realize the image was not purely documentary. In making these images Jerrems directed friends and associates, including students from the college where she taught, reflecting her work with him and filmmakers.

In his essay accompanying the exhibition A Decade of Australian Photography 1972-1982: Philip Morris Arts Grant at the Australian National Gallery (1984), curator Ian North tried to articulate the particular appeal of Jerrems’s work:

When her subjects do not overtly project their personality they are rendered in a manner suggesting gentle compassion and intimacy. Jerrems’s best compositions have a casual perfection: Vale Street has justifiably become an icon of 1970s Australian photography, yet seems free of forced formalism and mere chance.

For others the image connects with the lines, “I am woman, hear me now,” from a 1972 hit song by Australian singer Helen Reddy. It also seems to playfully assert a kind of Age of Aquarius paganism in which the “goddess” reigns over her male companions. This pretentiousness breaks up in another image, Mozart Street, [Fig. 5], which was clearly taken soon after Vale Street, with the same three characters, and is frequently exhibited with it. Are we meant to understand that there is play-acting and self-invention also involved in Jerrems’s scenario?

Her images will not give up neat readings to suit fixed agendas. In Jerrems’s work there is no particular call to action, but a call for certain sympathy.

Despite the rhetoric of the “new photography,” many 1970s photographers clearly worked within existing traditions of documentary photography.

Roger Scott was one of the most respected of the roving “street” photographers.

Compared to the work of older documentary photographers, such as European master Henri Cartier-Bresson and his concept of photographs as “decisive moments,” there is a new tension in the seventies images between the universalized humanism of the genre and the often alienated point of view of the counter-culture. In Scott’s image Ghost Train, [Fig. 6], the swinging, long hair of exuberant young men seems to be shaking off the repressions of the past.

Scott approaches his subjects largely unobserved — even when he locates himself in the pool [Fig. 7] of one of Australia’s famed beaches. There is visual wit but also a tension bordering on frenzy in his urban scenes; this has led to such approaches being labelled the “urban bizarre.” The generations in these images remain isolated from each other. |

|

|

Traditional Australian culture seems pathetic and tired, with such degraded rituals as the beer-drinking Aussie blokes in Rocks celebration [Fig. 8]. In Easter Show, [Fig. 9], a cow appearing to fart in the face of a prim old lady epitomizes the “uptightness” which so repelled the young.

A survey of the images of these years reveals a fascination with both the very young and the very old. The old rarely possess the wisdom of age. With such a large number of photographers placing importance on personal expression, the range of approaches to photography represented in the Philip Morris collection is very varied.

Nevertheless, there is a quality of homogeneity among the works from the seventies which contrasts with those produced after 1980, with the appearance of color and mural prints as well as large installations. Most art photographs of the seventies were in black and white (print color did vary from mat, rich browns to cool, blue-tone glossy surfaces) and small in scale. Selections reflected the view that a photographer’s work was best seen across a body of work. Many chose to present a sequence of images which emphasized, as Moore has suggested, the special relationship of photography to “the soft spread of time.”

Such serial imagery may have been inherent to the medium but the preference for a mosaic strategy also related to political notions that favored equality and preferred a many-layered approach to invariable certainty. Jon Rhodes frequently sequences his images combining formal, precise elegance with a political position. Much of his work has been involved with recognition of Aboriginal land rights issues (see page 58).

The range of subjects was not so varied. In the introduction to the first major publication on the photographs in the collection, Australian Photographers: the Philip Morris Collection (1979), selector James Mollison noted the lack of images of the outback and other stereotypical views of Australia and the frequency of images of the artists’ friends and their dogs.

He did observe the continued gravitational pull of the beach, a subject encountered, he wrote, in hundreds of portfolios: “Today, the most constant preoccupation of our photographers is the beach and swimming.”

By way of explanation, he had been told by a photographer that “the subject is always there and can be counted on to provide a strong image.”4 This is not surprising, given that most of the images in the collection came from Sydney and Melbourne, where beach cultures had flourished since the twenties.

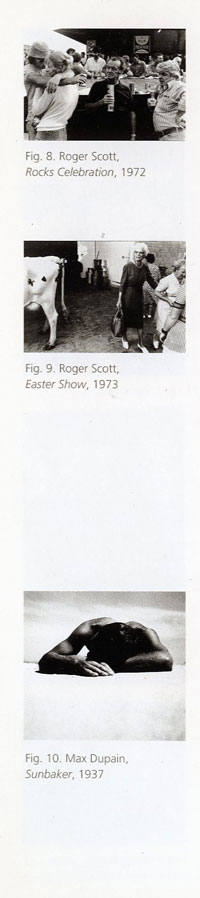

In his Philip Morris selections, Mollison had also included the 1937 image of a bronzed sunbather by Max Dupain, one of the best known of the older generation of Australian photographers. The Sunbaker, [Fig. 10], which had hardly been exhibited of published before the 1970s, quickly established itself as an icon of Australian photography and eventually as a national symbol.

Lacking any of the clothing or objects which date other early images, Dupain’s sunbaker seems forever in the present. The current popularity of the Sunbaker and Dupain’s body of documentary images from the 1930s to the 1950s is in part nostalgia for an era when the bronzed “Aussie” was king of the beach and values were clear cut, without the gender and multicultural politics of today. |

|

|

For Dupain, the beach and the water’s edge were the sites of dynamic interaction between nature and people. For the younger contemporary photographers who prowled the shorelines in the seventies, the beach was more than just a place where you could count on a “strong image.” It was a stage for strange conjunctions of people and places.

In some images, the faded pavilions and amusement arcades appear as ruins from a past era during which Australia was closely identified with its urban beach lifestyle. One of the strategies of the counter-culture was a desire to recover a sense of wonder and play.

The association of beaches, fairgrounds, and circuses with the lost fun and reverie of childhood may well account for the popularity of such subjects as much as any purely formal characteristics. In support of this theme, children and animals are also well represented as subjects in the Philip Morris collection. Robert Ashton made many images of beaches near his home on the coast of Victoria. His image of dogs ecstatic with the wind and waterside freedom of the beach, [Fig. 11], and a clown at dusk have a magic realism as well as a sense of being there and of being “into it” at the same time.

William Yang is an Australian of Chinese descent who worked in the seventies under the anglicized name of Willy Young. His 1980 image of a young “surfie” in Bondi, [Fig. 12], resonates with the strong formalism and machismo of Dupain, while the long bleached locks of the youth locates it in a specific culture and time. Yang’s professional and personal body of work in the seventies revolved around the trendy subcultures and the gay community.

Images in the Philip Morris collection by Yang and Rennie Ellis point to the flourishing alternative cultures then still kept away from the eyes of middle-class Australia. In recent years Yang has engaged more publicly with his cultural and sexual identity, making major works in response to the AIDS crisis.

Although a number of the 200 or so photographers at work in the seventies came from multicultural backgrounds, few explored cultural diversity in the way of those working in the 1980s. Aboriginal photographers did not appear in significant numbers until the 1980s. In the seventies, “Australian” still largely meant Anglo-Saxon.

Rennie Ellis’s underwater image of a child subjected to the sink-or-swim method of training is delightfully ambiguous [Fig. 13]. Is the child victim or free spirit let fly? Merryle Johnson essays the old genre of the nude underwater, her “mermaids” countering gender politics with a celebration of sensuality [Fig. 14]. Woman and water was a theme as old as Aphrodite’s birth on the seafoam.

Australian photographers in the past had been very prim. In the thirties, Dupain had made virtually the first serious studies of the body. The free love and sensuous freedom extolled in the sixties and seventies made the body a popular subject. Romantic images of dreamy women dressed in “tat” shop faded glamor, then popular in fashion, were also a feature of the times. In his images of women, objects and places, Robert Besanko developed a printing style using Kodalith tonal drop-out papers, which had the feel of an old movie [Fig. 15]. |

|

|

A majority of the images from the seventies fall within the orbit of a personal documentary naturalism and were predominantly figurative and urban in subject matter. In addition to the moody energy of the more traditional documentary work, there were more formal and deliberate photographers like Steven Lojewski [Fig. 16]. They often worked with larger format negatives and stand cameras, crafting their prints with sensitive skill. Their pictures were independent of their subject while revealing some aspect of a place or object in a way which emphasized the qualities inherent to photography as a process and as a way of seeing.

Other photographers like Mark Johnson, [Fig. 17], and Ian Lobb, [Fig. 18], were “devotional” in the sense of using photography to venerate aspects of the built or natural environment. Among the most abstractly formal works in the collection are Grant Mudford’s impassive images of urban topography [Fig. 19]. They draw on aspects of pop and conceptual art as well as the then current issue of flatness versus description in abstract painting. Mudford’s mute images are the frozen sections of some recently excavated city, the inhabitants of which having inscribed the walls with the names of the gods they worshipped, like MEX, FABMAGIC and LA.

Such fantasies are created by Mudford’s technical sleight-of-hand, which keeps a fine tension between graphic lines and patterns and a viable rendition of a real three-dimensional space with objects. Ultimately Mudford’s cities are witty, false eternities which collapse with the next breeze or passersby.

The flattened perspective in his later images is partly achieved through the use of a perspective correction lens, which straightens the verticals, and a point-light source enlarger, which defines the grain as sharp pin points across the surface of the print.Landscape in Australian photography has not enjoyed as much prominence as this genre has in British and American photography.

However given its dependence on particular locales and features, landscape work is the arena in which the greatest regional differences appear. Some photographers, particularly those in the cooler southern climes of Victoria and Tasmania, have been inspired by European and American traditions of the fine print and the deliberate nature study. Ian Lobb [Fig. 18] and Les Walkling [Fig. 20] (who also makes constructed studio allegories) are among those who studied landscape photography in America. With a deeply felt metaphorical view of nature, their work connects strongly with literature and music and usually involves great commitments to intense discovery of particular terrain.

A different approach is employed by Wesley Stacey who started work in Sydney in the 1960s and later took to permanently travelling the country by road in a camper-van. He is less concerned with defining every tonal nuance by using very fine printmaking techniques. A combination of a background in graphic arts and an influence of the hedonistic delight Sydneysiders take in light-filled, energetic surfaces and decorative flourishes is evident in his color and black and white images (see page 62). |

|

|

Stacey came to see his landscape work as part of the tradition of the colonial topographical views of depicting the features of the natural terrain and the places, spaces, and constructions of the people. His work has tried to recognize that Australia is also now a country inscribed with the spiritual concepts of the original Aboriginal culture as well as the western Biblical concept of a Garden of Eden.

Most of the photographs in the Philip Morris collection are “documentary” in the sense that they appear to reveal something about the aspect of “the world” as such. Some develop along the lines of the oft-quoted proposition by nineteenth-century writer, Emile Zola, that “a work of art is a corner of creation seen through a temperament,” (Mes Haines (My Hates), 1866); others use an original, quite direct image as the starting point for the artist’s vision and stage a world of their own, which is then given authority by the “naturalism” of the camera.

Bill Henson is prominent among artists who consistently deflected their images from any simple window-on- the-world naturalism or cool formalism. Throughout the seventies and up to the present, Bill Henson (he is to be the Australian artist featured at the 1995 Venice Biennale) has attracted the most serious and consistent mainstream arts appreciation for his work. He has produced series of images which offer fragmented and ambiguous narrative readings but subvert the idea of the explanatory “photo-essay.”

His Untitled series of 1977 (see page 44) was seen at the time as rather progressively homoerotic despite the fragility and androgynous appearance of the languid, thin and pale youth. These and later works frequently centered on rather forlorn figures in realms in which the bright light of day never illuminates the relations between things and people. The beach, bush or any “typical” Australian element is never in sight.

Warren Breninger, a deeply committed Christian, is unique in his method of working over and over a few selected images — initially the head of a young girl — in a variety of media. The attention given to his ongoing Expulsion of Eve series [Fig. 21] was substantial in the late seventies and its degree of savaging of the pure print was far more accepted than the mere use of handcoloring by many others. His images confront the dilemma of flesh and spirit, physical decay and eternal life, and love, sacred and profane.

Australian photography changed dramatically just as the ledgers on the Philip Morris collection of Australian photography were closed in 1981. By the early 1980s, a strong, new “new” generation appeared who largely rejected the naturalism still inherent in personal documentary work. Color and mural-size printing progressively became the norm in the 1980s, rather than the exception it had been in the 1970s. Large installation and studio-based “tableaux” photography became a major vehicle. Women seemed particularly at home with the staged image. Many works were overtly “quoted” from a menu of past styles of art. |

|

|

Documentary photography or work which focused on nature and society was increasingly perceived by practitioners as being devalued and hijacked by agendas set by the art world.

In looking back after two decades, the works in the Philip Morris collection are still a rich lode. Some serious and well-sustained criticisms (by Anne-Marie Willis, for instance, in her Picturing Australia, 1988) have been of the assumptions and social hollowness of the rhetoric of personal expression adopted by so many of the practitioners of the time. Perhaps we are not yet far enough away to see the images anew.

Much new critical analysis has been devoted to more recent contemporary work or much older Australian photography. To crudely characterize the more formalist work as shallow and that which addresses social issues as more worthy, or to assume that a picture without people says less about the society it came from, is potentially as fallacious as the refusal to see deep formal, metaphorical and spiritual language in a penchant for handcoloring.

As the artists have developed, some like Micky Allan returning to painting, the parts of their work which have remained indicate that their early works need a more refined analysis and one which recognizes that the best imagery of the period is far more sophisticated and multilayered than any one reading permits.

Perhaps the current presentation of a selection of works from the Philip Morris collection of Australian photographers of the seventies will be the catalyst for a new examination of these works.

Notes:

1. Quoted in Graham Howe, ed., New Photography Australia: A Selective Survey, Sydney: 1974, p. 40.

2. Ibid., p. 56.

3. Personal communication with the author, October 1994.

4. Quoted in James Mollison, introduction to Australian Photographers: the Philip Morris Collection, Melbourne: 1974, p. 4. The photographer is not named.

Links to pages for On The Edge:

Introduction page to the online publication

Australian Photographers and the Philip Morris Arts Grant, 1973- 1988.

Top of this page: The Soft Spread of Time: an essay about the photography and the photographers in the exhibition.

The Plates: Australian Photographers of the Seventies

The Checklist for the exhibition

Biographies of the Artists: compiled by Anne O'Hehir

|