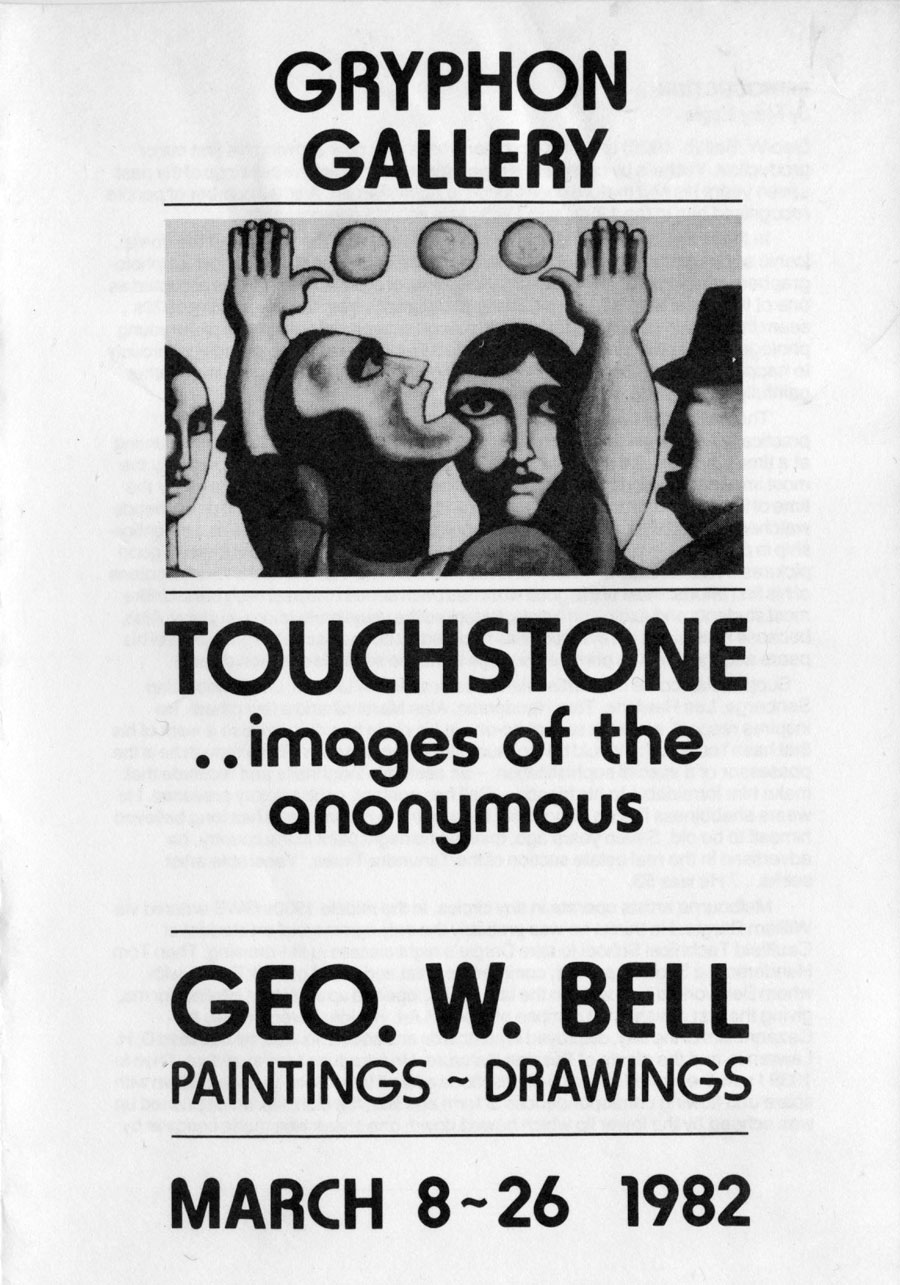

George W Bell

Mary Eagle, December 1981

Text for the catalogue of an exhibition of Geo W Bell’s paintings and drawings at Gryphon Gallery, Melbournne, 8-26 March 1982

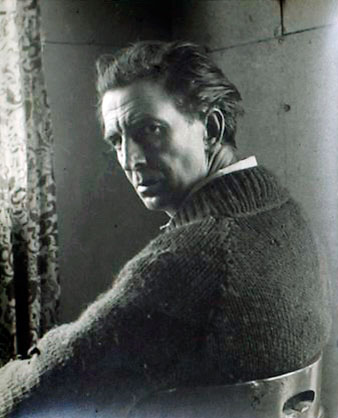

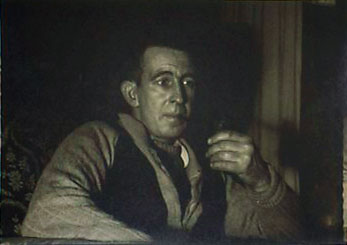

Geo W. Bell (b.1920) is old for a painter who is only now showing his first major production. Yet he is by no means a newcomer to art nor are his paintings of the past seven years his first mature contribution to Australian art. A small number of people recognised him in the 1950s and 1960s as a notable photographer.

In those times his aesthetic of non-interference with the image and the frontal, iconic appearance of his photographs made him unfashionable amongst art-photographers interested primarily in formalism. Now of course, directness is accepted as one of the 'pure' tenets of the art. Many photographs from the burgeoning 1970s seem the progeny of Bell's earlier work, though actually only one or two of the young photographers ever saw it. By the time this new photography began so vociferously to happen in the 1970s GWB had stopped photography and was dithering rather painfully about going back to painting.

The two transitions in thinking, the first leading into photography when practically no-one else was doing it his way, the second taking him back into painting at a time when a great many artists were turning to the camera, are probably the most important periods in his career. I cannot explain why they took place. |

|

|

By the time of the second change I was a friend and with his wife, children and other friends watched as he gave up his job and stubbornly pushed into a full-time re-apprenticeship in painting. He was not confident about the chances of being able to make good pictures. A harsh critic of others' and his own work, he saw the faults and limitations of his first efforts: most of the good work has been done in the past two years. Unlike most students and exhibiting artists he lacked the usual professional support. Also, because he is older, his evolution has necessarily been against the grain both of his peers and the times. A prime advantage is that he sees his situation clearly.

Support has come from artist friends such as Kevin Lincoln, Len French, Jan Senbergs, Les Hawkins, Tom Henderson, Alan Marshall and a few others. He inspires respect, so much so that no one in his circle has dared praise a work of his that hasn't come off: it would be too much like letting him down. But although he is the possessor of a special sophistication – an aesthetic toughness and rectitude that make him formidable to his friends – Bell has another, contradictory presence. He wears shabbiness like an armour, he is eccentric in manner, and has long believed himself to be old. Seven years ago, thinking he might paint in the country, he advertised in the real estate section of the Tanundra Times, “Venerable artist seeks...” He was 53.

Melbourne artists operate in tiny circles. In the middle 1930s GWB entered via William Dargie. He thinks he was probably the only commercial art student at Caulfield Technical School to take Dargie's night classes in life-drawing. Then Tom Henderson, a Scottish painter, commercial artist and friend of Jock Frater, with whom Bell worked for a while in the late 1930s, “opened up a world of intellect for me, giving the first devastating glimpse of Modern Art. His ideas were mainly the Cezanneism of the day, displayed in postcards and books. As well he had read D. H. Lawrence and the giants of Russian literature. He introduced me to all that. Then in 1939 I saw the Herald show”.

Bell describes a head by Matisse that was drawn with spare and flowing correspondences of form and line; the chin line which pushed up was echoed by the lower lip which bowed down; one cheek was made concave by the curve of hair while the other cheek bulged.

Bell admits a lasting debt to Matisse who “had such an influence that I'm drawing as I do now. For the first time in this picture I could see how color and form are welded into a plasticity as against merely filling in areas”.

Henderson would have spoken about plastic form (he had books by Roger Fry) but now GWB experienced it. Melbourne painting was “such a miasma of muddy browns the exhibition was cleansing”. Derain, Van Gogh, Cezanne, Vlaminck were represented and in those days (not now) he could see the merits of Dali's picture.

The rapid evolution of GWB's taste scarcely matched the practicalities of his life. For a while he had a job silkscreening cutouts of Pop-Eye the Sailorman (destined for slippers) at Henderson's little business, Ardell Displays. In 1936 he won a prize for a poster ‘Join the March for Peace’ in a competition held by the Victorian Council of the World Peace Congress at the University of Melbourne. (newspaper photo attached)

He kept on sketching into, through and after the war, though art was ostensibly interrupted for six years (1940-6) while he served as a conscripted soldier. In fact New Guinea fueled an interest in ethnic art that had begun in childhood when an uncle sent down New Guinea artefacts. By the time GWB went there as a soldier he had a rudimentary knowledge, enough to see the art and then to actively seek It. He learned to speak Pidgin.

Like a number of young artists caught by war service, GWB found difficulty in settling down afterwards. For some years he wandered, not the sensible course for a poor young man 'with art ideals' who could have taken a Rehabilitation course at the National Gallery School.

He went back to New Guinea – more ethnic art – and in Australia he went to New Norcia, a mission 70 miles out of Perth, hoping to see the work the Marist brothers were doing with aboriginal art. He travelled to South Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland, eventually in 1948 settling for two years in Sydney.

There he worked as a ships' painter and docker, becoming acquainted with the Society of Realist Artists (SORA) art fraternity in the Kings Cross-Woolloomooloo area. People deeply involved in the Studio of Realist Art were Hal Missingham, Rod Shaw, Herbert McClintock – communists, “We weren't communists but went to the life-classes for the utilities”.

Bob Fosbery (an international figure in film animation), Gordon Walters, Charles Blackman and Laurie Hope were there. Laurie Hope was “painting very well at the time - pictures of embryonic children floating in space”.

Blackman “was a virtuoso draughtsman in the life-class. The only thing I remember about his work then (a couple of years before he began exhibiting) is an affinity with Nolan's work of the time. Thin veneers of sepia paint were cut by pink silhouettes in a kind of calligraphy. He liked still-lifes of such subjects as a head superimposed above a vase of flowers”.

Bob Fosbery also “showed a feeling for Nolan's type of work. One of the most gifted of us compositionally, he was a profound influence on young Blackman”. Bell says his own paintings of the time were ponderous. He was preoccupied with structure and never tried the fugitive effects of his companions at SORA.

These dozen years between meeting Tom Henderson and returning (married) to Melbourne in 1950 are the formative period. Despite the gap in years, and the aspects of his recent paintings that stem from a knowledge of art between, Bell's interests now are those he felt then. They may be summed up in the twin debt to ethnic art and Matisse: the emphasis on structure, line, the push-pull of shapes and masses and, at the centre of his concentration, figuration.

He told me once that the art he most liked was “more real than real”. If the Romanesque sculptor, for instance, “wanted to show Adam with an apple in his hand he enlarged the hand and apple, reconciling them with the rest by various distortions all through- the figure”.

Why did he turn to photography between 1952 and 1972?

On the surface it would seem that a machine-recorded image is poles away from the icon GWB appreciated. I am guessing when I suggest that in photography GWB avoided the fissure that opened in painting in the 1950s and 1960s.

Painters struggled with conflicting desires. On the one hand they desired to express ideas and life forces, on the other their perceptions shifted towards seeing the act of painting as the centre of art. The breach between figuration and formalism that bedevilled Australian painting for two decades could be bypassed in photography where no matter how much attention was paid to the photographer's role he was obliged always to point his camera outwards to the other.

It was the iconic aspect of photography that attracted Bell. He met the photographer David Muir who, with George Johnston, was making collages and photograms. Interested, he began to look at early photographs. Muir showed him volumes featuring the 19th century photography of ‘Nadar’ (Gaspard-Felix Tournachon, b.1820), “pictures of old ladies sitting in rooms, naked, whom the photographer has given great dignity and monumentality by limn-lighting”. Nadar’s images have a quality of line combined with surface – effects which “haunt” GWB still.

GWB’s photographs and now his paintings refer back consistently to 19th century photography. He likes the mood of discovery. “We were aboriginals then, as absorbed by the machine as any newcomers, whether we were the one under the enveloping black curtain or the others staring back at the camera”. He likes the clarity and directness of early documentary photography, the fact that nothing is superfluous. A number of his paintings are based on photographs.

For example the two of a carter with horse derive from a fuzzy photo of sustenance workers on the Yarra Boulevard during the Depression (The Melbourne Scene1805-1956, MUP 19_, p.276) and Clem's Boy, 1981, refers to a photo in Bruce Howard's A Nostalgic Look at Australian Sport, (Rigby, 1978, p.95).

However, the source of the paintings is usually an anecdote, or remnant of anecdote. It may be someone he knew or a scene from childhood. A memory may be stirred by a news photo.

|

|

“The image of a cow struck by a car Conversation With An Injured Cow 1980, was inspired by Tom Henderson consoling it as it died. His daughter told me the story".

“I witnessed Jugger in the Street, 1981, as a child."

“Thirty thousand Vaults, 1979, was a sideshow down at Luna Park; the spruiker was saying "Thirty thousand vaults right through her beautiful body”.

“Seated Figure, 1978, is drawn from a woman seated in that posture, head on hand, whom I saw on a train”. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Juggle in the street 1981 |

|

Louis Brunel 1979 |

Returning to painting in 1975, GWB worked for a while as studio assistant to Len French. The first paintings were built into a textured surface after the manner of French. Literally he was creating in a stiffish medium the three-dimensional effects he so much admired in primitive sculpture, but the need he also felt to continually shift around the image while working on a painting made this a limitation. After thrashing about with various techniques and treatments he achieved a more truly pictorial monumentality through light and shade.

In seven years he has enjoyed the linear working-out, while the worrying underside of his effort has been color and surfaces. Despising facility and wanting every aspect of picture-making to be a positive part of the completed image he has labored to make color and paint texture integral to his manner of painting. Black-and-white photography and primitive sculpture feed a sense of form.

Sympatheric western painters are Fernard Leger, Balthus, Constant Permeke, Matisse. Less immediately obvious is the influence of 1940s-early 1950s School of Paris paintings. The exhibition 'French Painting Today', shown at the NGV in 1953 “devastated” GWB, particularly Andre Marchand's largeish painting Spring.

In approach iconic, still looking for what is most distinctly itself, always focusing on the ‘thing’, GWB carries each image through numerous sketches and painted versions. He said

“We are atuned to types, but it is only when we see exceptions that we consciously know the type”.

His art has moved beyond photography, partly because it is achieved more plastically, –by making and manipulating the image until it is “more real than real” – and also because its sources are often unphotographable mental images and evocative memories.

December 1981

>> more paintings <<

use the menu above and below to explore so much more on George W Bell

|