Bernard Otto Holtermann

>> see also A. P-R. 1953

Australian social history suffers from from many missing chapters. One of the more obvious gaps is that so little is known of the individual miners who reached here in their untold thousands in the great days of gold. Certainly we know that they come from almost every country, that they were venturesome spirits of enterprising personality — but that is about all.

Most accounts of life on the goldfields were written by overseas visitors, local travellers and journalists. It would hardly have occurred to the average digger to write about himself1, for he had far more pressing matters to worry about in the ceaseless search for rewarding specks, or more happily, nuggets, in the tail of his dish.

Bernard Otto Holtermann was an exception Among gold seekers in leaving behind him a substantial Amount of biographical material. The earliest domlment2 is a brief account of his life written in the earlier part of 1876, just before he and his family left Australia for their trip abroad.

Although couched in the third person, the handwriting is readily identifiable as his own. It consists of sixteen octavo pages and records the details of his voyage out to Australia and was apparently compiled for use in possible interviews abroad. No alterations have been made in the following extract, other than some corrections of spelling and insertion of punctuation.

"B.O.H. was born in Hamburg, North Germany, 29 April 1838,3 and was for 5 years employed in a Mercantile House of well-known Repute as Holtermann & Kopke, and of late years, H. H. Holtermann In 1858 he made up his mind to see the world, or rather far-famed Gold Land, Australia, more so as he had a brother in this Colony for Several years; and, secondly, he did not believe to be dressed in Military Cloth or lose three years of the best of his life as a Soldier. He made a start from Hamburg in a steamboat to Liverpool on the 15 April without any English Language. Started per train to Liverpool; stayed at Liverpool in a Boarding House for ten days with many a little Narrative in this large City as a Memory.

Then was embarked as a Steerage Passenger in the Ship Salem, Capt. Watt, for Melbourne, and started from Liverpool on the 29 April. On the starting he was surprised, as a sign of bad luck, as he terms it, by a large Piece of timber being thrown on his foot, completely crushing his big toe, but, to wind up at night, he was laid up with the beautiful Sensation of Sea Sickness, combined with being partly Heart-broken without a friend to care for him except an American Native then Cabin Cook on board, who attended to him like a father and brought him nice things to eat until he recovered from his Sickness, some 14 days, but more like 14 months to him.

He then took (it upon himself) to assist the Cook whenever he could and received nothing but kindness from the whole ship, principally the Captain who was as nice a man as he ever met. Several dozen incidents occurred on Board of which he related one or two (to the interviewer. Some of these related to the thieving habits of the crew, while another was when, while trying to oblige the Cook, he slipped in rough seas with a pudding he was carrying; both he and the pudding went rolling a11 over the deck to the amusement of the others. Another was the time when he saw two men fighting for about half an hour, only to see them shake hands when one had gained the victory. Following several deaths on board) he tried his medicine on a German woman very weak and nearly exhausted and was afraid she had to follow the others, but thinks he saved her and several others from Severe illness or death.

Many more memories he has during his Passage, which he fully intends Publishing in a small book shortly . . .'

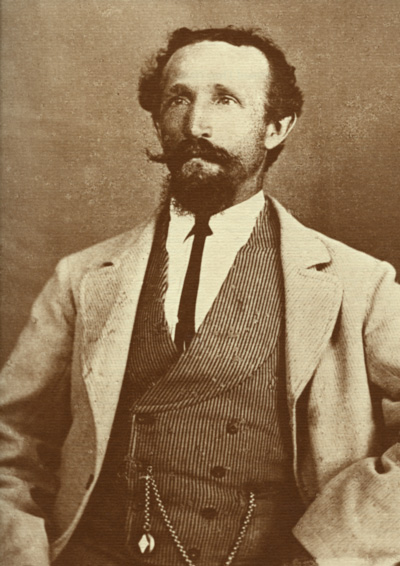

Bernard Otto Holtermann; portrait taken in the studio of the American & Australasian Photographic Company Hill End, 1872. (777)

The survival of this document is valuable for not only does it convey some essential facts but it also epitomizes Holtermann's character and outlook on life — his natural friendliness, his sense of humour, his interest in medicine and, above all, his continuing charitable regard for the welfare of others.

Furthermore his language difficulty and quaint English, his narrow escapes from serious injury were to recur during his life. We must indeed regret that his 'small book' of experiences never saw light of day; his thoughts in later years turned from personal experiences to larger issues in the political sphere.

The Salem reached Melbourne on 7 August 1858, having taken just over one hundred days. The passenger list is still extant and shows Berhard Haterman (sic), 20, foreign'. He then boarded the City of Sydney, reaching the city of that name on 12 August in the evening.

He immediately went ashore to search for his brother at several addresses only to be told that he had gone to the diggings. Unable to find employment and unfamiliar with English, Holtermann's eventually secured a berth as a steward in the schooner, Rebecca, 114 tons Captain Souter, which sailed on 13/14 September to trade in New Caledonia and the South Sea islands. Rebecca returned to Sydney, via Port Cooper and Melbourne, on 17/20 January 1859. He now

'. . . tried many a billet that was advertised as Waiter (sic) in Photo-Gallerie, at North Shore as a Groom to mind a little Pony and occasionally pull a Boat to Sydney which was just filled by someone else, and many other trails, until he engaged as honourable Waiter in a Public House . . . then the Hamburg Hotel5 in King Street for ten shillings pr. week, but the owner, a Gentlemanly Master, gave him 12/- instead.

' He stayed there for a five month, had some experience with Gold Miners principally one very rich one from Adelong. At them days he did not like his billet and was going to Adelong or Fairfield.6 But his late Mate, Mr Meyers7 stayed at the Hotel and he made up his mind to have a trial at the then worked-out Tambaroora Goldfield, or Bald Hill, now Hill End,8 and he never left it for the first five years through not having much money but has many little anecdotes and Memories to refer to as a digger and many other occupations that came to hand. In 1861 he started with Mr Beyers Prospecting Hawkins Hill and never entirely left it to the present day and still believes in it . . .'

From this point the memoir becomes somewhat fragmentary, but in an earlier interview in the Australian Town and Country Journal, 2 November I872, he recalled 'the deep satisfaction he felt when, as a weary traveller, he reached a shady spot on the hill above Tambaroora and threw down his sixty-pound swag. The painful experiences of that dreary journey, though a desolate and trackless region, made him at times feel that it would never come to an end, that he must die on the way; but, on reaching the heights, he felt hopeful and contented.'

Only too soon was the contentment to vanish, and likewise the magic of the place with the strange-sounding name which had so often excited his imagination when he heard the field discussed by the diggers at the Hamburg. Success in finding gold depends on luck almost as much as on experience and at that time Holtermann had neither, and nearly nine years were to elapse before he was able to achieve any real financial stability.

Although it would seem that he and Beyers crossed the mountains in company, they do not appear to have been mates on an important claim until 1861. The memoir also states that Beyers was always ready to help him with money and labour. He is probably referring here to the Star of Hope claim which was eventually to become so famous, although references to other claims are mentioned in the Holtermann papers.

Holtermann and Louis Beyers photographed on top of the Hawkins Hill Ridge. There was no flat ground in the vicinity of the mine shaft for shaft timber storage. (70197)

Meanwhile Holtermann was involved in several narrow escapes, the last and worst of which was when some 'fourteen pounds of blasting powder (exploded) when he was within a couple of feet of it, hanging on a rope twenty feet from the bottom of the shaft and one hundred and ten from the surface'.

Holtermann's name is recorded as being associated with several well-known reefs as early as July 1864, whilst Beyers's Reef is noted several times during 1865 and 1866.9 The Star of Hope claim is not mentioned by name until 24 August 1868 when Richard Kerr was granted 'time-off'.

It was the Star of Hope in which the partners had the greatest faith; nevertheless there were hard times when portions of shares had to be sold to keep the claim going. In 1867, he made 'a few hundred pounds from a surface crushing10 and this enabled him to build and manage an early hotel in Hill End, the All Nations Hotel in Clarke Street. It was at Holtermann's hotel that, following the attempt on the life of H.R.H. Prince Alfred at Clontarf on 12 March 1868, a patriotic meeting was held to express the loyalty of the settlement. However he held the licence for one year only, selling out to one Nicholas Lambert on 26 August.

Earlier in the some year, on 22 February, at the Church of All Saints in Bathurst, a double wedding was celebrated when Holtermann and Beyers married the sisters Harriett and Mary,11 daughters of Edward Emmett of White Rock, a family well known in the district.

The reason for Holtermann's sale of the hotel was his desire to set up substantial new enterprises, first at Chambers Creek and subsequently at Root Hog, but both were to prove disastrous. He and his brother, who had now joined him, were reduced to acting as ferrymen, conveying travellers across the river (the Macquarie) when it was too high for fording. The ferryboat was exceedingly primitive, having been converted from a baker's mixing trough.

Work was still continuing on the Star of Hope; the expense was heavy especially on account of the necessity for timbering. To obtain both funds and labour, more partners were taken in. To original syndicate members Richard Kerr and H. Miller were now added John Klein, James Brown, and Moses Bell; the latter not actually working in the shaft but represented by a miner on wages, William Hunt. Holtermann's brother worked there at one time but does not appear to have held a share. The new syndicate members lightened some of the burdens but rewards remained very small. Yet there were surprises ahead that none could possibly have anticipated.

About April 187I, there come on to the market an eighth share in the claim - that owned by James Brown. Brown was a well-known identity on the held under the familiar name of Northumberland Jimmy; he had come early to Hill End and had been very successful, so much so that he was now clearing up his affairs prior to returning to England. He offered his share for £500 to another early resident, Mark John Hammond,12 who had long coveted it.

Hammond could not lay hands on the money, but, having certain definite ideas about the claim, he approached his good friend and Star of Hope syndicate member, Moses Bell. Moses Bell not only advanced the £500, but also provided direct encouragement by giving him the right to control the work of his own wages man, Hunt. However four months passed before Hammond could put his plan into effect, for work had to be suspended owing to top claim workings.

A few shifts on the claim were sufficient to convince Hammond of the truth of the opinion which he held, namely that the syndicate was unlikely to locate any rich veins by further sinking. In vain he tried to convince Holtermann and the others, but finally, assured of Bell's support, Hammond decided to take matters into his own hands. One evening, when he and Hunt come on shift, they cut timbers, sealed off the shaft about 130 feet down and rapidly commenced a new drive to the west. What happened when the day shift arrived is vividly described in Hammond's memoirs : (The looks on their faces are still in my memory, never to be forgotten. What they were going to do and what they would not do, was something awful. I had ruined the shaft and would have to pay dearly for it!

'We got to very high words. 1 threatened to wring one of their necks, and was in return threatened with a knife. They knew that I had them in a fix, and that whether they worked or not, the drive would go in. The only way they could stop it was by applying for an injunction to restrain me.

'They had several meetings amongst themselves, but nothing eventuated. They came regularly at the time to change shifts without a single word being uttered, good, bad or indifferent. All the talk was in the town as to what I had done. Bell stuck to me like a brick. Every morning during the week we found that no work had been done by the other shifts, but Bill Hunt and I kept pegging away.

'We were on the night shift the following week when I had the extreme satisfaction of cutting a vein full of gold. This was at 11 o'clock at night. We knocked off and reported the find to the party. The report of the discovery flew like wildfire. One would have thought these men would have been ashamed of themselves for the way they acted, but instead of that, one of them rushed to the newspapers, leaving it to be inferred that he was the discoverer, and kept his name emblazoned before the public for years afterwards. I had nothing to gain by disputing the matter. 1 had found the gold and was well satisfied with that fact.'

The find was briefly reported in the Australian Town and Country journal for 2 September 1871 and again, in the some paper three weeks later when accurate details as to the various veins were communicated by Hammond himself. He later sold his share at a handsome profit, moved to Sydney and subsequently became a man of substance, but Holtermann held on and saw his fortunes rise dramatically. With the backing of his many local friends, Holtermann accepted nomination as a candidate in the new Goldfields West Division (which included Hill End) at the forthcoming state election.

Alluvial fields, no matter how rewarding to the individual hard-working miner, offered little attraction for easy-money speculators. Quite another matter, however, were the possibilities latent in reef gold. An era of reckless speculation followed, stimulated by the rich fends at the Star of Hope, its neighbour northwards, Krohmann's13 and a number of others.

Following on the Ending of rich quality veins on Hawkins Hill, there was an influx of strangers to the district — speculators and company promoters — as had never previously been seen. Before the year was out no less than fifteen hundred claims had been staked out and shares in these futureless mines were being offered on the Sydney market, backed by exaggerated references to the fabulous riches already won from the field.

As, day by day, the news reached Sydney of the astounding results of the regular rich crushers of gold-bearing stone from the various claims along the Hawkins Hill line of reef, a frenzy of speculation developed. For a year or more — or until shareholders found themselves unable to meet their calls — this wild speculation continued, propositions based at best on the existence of payable gold somewhere in the neighbourhood, or, at worst, on the exhibition of working faces peppered with gold obtained from filed-down nuggets or sovereigns. Mines with good prospects saw their hopes for adequate finance swept away, overwhelmed in the torrent that had been so skillfully engineered by swindling speculators.14

This trend of events could not but alarm the more responsible citizens of the district, among them Holtermann, who lost no time in writing a warning letter to the Sydney Morning Herald, which duly appeared on 20 November :

'Noticing in several newspapers so many accounts or reports from Hill End, and even telegrams, which are but founded on some very slight or unsafe foundation, or mistakes — who knows which — I feel it my duty as one of a large community to state a little about these so well blown-about gold-gelds as Hill End.

'I would advise no one to buy in any claim, lease, etc., without he is well acquainted with the party selling, or has someone responsible on the spot to refer to, or who the purchaser can depend upon: if not, he had better spend a few pounds, and look for himself.

'Do not fancy that the whole of Hill End or Tambaroora are going to turn out to be rich or fortune claims. It has never been, and it is not likely it will be the case, more so the way it goes ahead now, because a man need only go and take up a lease — never mind where — blow well, and misrepresent the same, and he can raise plenty of money — never mind if it never turns out a grain of gold, it fetches money to Hill End.

But how long? Not for many months because the paying parties, not the sleeping shareholders, will get tired, and give their interests up, run the whole place down to be no good. . . . Several claims are really rich, but how far the richness runs along, no one can tell, and where it is to be found no one knows. The oldest digger knows no more than a new chum in regard to where the gold is in the ground . . .'

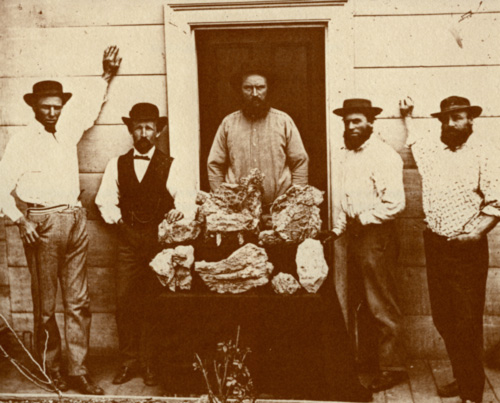

Holtermann (left) and Beyers (right of doorway) with smaller specimens of reef gold from the Star of Hope mine. The central-figure is thought to be Richard Ormsby Kerr. (10" X 12'' series)

It is unlikely that any of the credulous and gullible of Sydney Town heeded Holtermann's warning, or, even, for that matter, read this strangely worded, almost incomprehensible epistle, its message concealed in the small type allotted to correspondents in the pages of the Sydney Morning Herald. But in the region of Hill End, upon the arrival of the issue in question on the eve of polling day, the reaction was electric. Copies were seized on by the opposing electoral faction, scores of dubious characters clearly saw their schemes threatened and their pernicious practices in jeopardy, while many of the more responsible citizens were alarmed for the success of promising new developments, even for the future of the town.

Tempers rose and, on the morning of 26 November, polling day, a large crowd, variously estimated at between one and three thousand, angrily assembled in Clarke Street. Holtermann's action was denounced and his effigy (or portrait?) burnt on a nearby hill. He was branded as a traitor by the Hill End and Tambaroora Times15 in an editorial — which was rather a surprising volte face, for the paper had long held itself out as something of a wise authority on matters relating to mining investment.

On Holtermann's return from Sydney, he wrote a scathing expose of the situation and challenged all and sundry to come forth and deny the truth of his remarks. We do not know whether the letter was actually published, but at any rate when he emerged from his house and paraded the streets, not one of the many persons who had promised to tear him to pieces was to be seen. As for the election, in the end he lost by a mere five votes.

>> see also A. P-R. 1953

It was now 1872. Early in that year Holtermann would undoubtedly have read with care his copy of the Australian Town and Country Journal for its excellent mining reports. He would also have noted a name new to him. Beaufoy Merlin had written in an entertaining yet factual manner regarding his participation as an official photographer in the recent Victorian — New South Wales Eclipse Expedition to Queensland, an account which the editor deemed worthy of a full page.

He would also have noted that Merlin was a photographer as well as a writer; indeed he must have been an expert to have been selected as official photographer to the N.S.W. section of the Expedition.

17 February 1872 saw the flotation of the Beyers and Holtermann Star of Hope Gold Mining Company (Limited), with a capital of £72,000 in shares of £1 each, the two senior partners retaining the major portion of their interests. This sum was a comparatively modest one, since four or five of the contemporary flotations ran into six figures. Holtermann stipulated, very wisely as it turned out, that he was to be appointed mine manager.

Towards the end of the following month Beaufoy Merlin reached Hill End and at once inserted in the Hill End and Tambaroora Times a notice declaring the photographic service which the American & Australasian Photographic Company was now offering. It can only be a matter of speculation as to the exact date of his first meeting with Holtermann.

But, at any rate, within two months, allowing time for the wood engravings to be cut, two striking panoramic illustrations of half-page size, appeared in the Australian Town and Country journal, dramatically depicting the great reefing area along the western slope of Hawkins Hill. Both were acknowledged to Beaufoy Merlin, otherwise one might well have thought that they were made from some of those cleverly-executed (bird's eye' views which were popular at the time. The original negatives are still extant in the Collection — of perfect technical quality in 10'' by 12'' format.

To obtain such a panorama a major operation must have been necessary. It involved moving the coating caravan, the large format camera and accompanying lens of long focus along a rough track to a distant westerly ridge where there had been previously erected, in a clearing on one of the precariously steep slopes which are everywhere on the northern side of the Turon, a high camera platform of substantial construction and absolute steadiness — made 'possible only by the erection of stages and appliances in the highest trees'.

The author feels sure that Holtermann must have been the key to this formidable undertaking. It is quite unlikely that there could have been anyone else in Hill End, who, at once, was interested in photography, likely to feel sympathetic towards such a grandiose pictorial vision, possessed the necessary finance as well as being able to provide the bush carpenters and other labour.

First in Hill End and later on in Gulgong, Merlin continued with his house-to-house coverage. Holtermann had his mine managership to occupy him (but he was on several occasions reproved by the Board for unauthorized absences). The Star of Hope was slowly but surely moving to its astounding crescendo. In ' the Hill End Observer for 22 October, it was reported that 'two new veins have been cut which promise a rich return; the richest vein, from which the specimens were taken which so excited the wonder of the people of Hill End about a fortnight ago when they were exhibited in Mr G. Hodgson's shop window, can now be seen in the face of the workings through nearly the whole extent of the claim, while innumerable other gold-bearing veins, some with heavy gold, are also to be seen.'

Early on 29 October, a final charge was exploded by the evening shift at about 2 a.m. in order to leave work for the incoming morning shift. That charge disclosed a veritable wall of the metal, the world's largest specimen of reef gold. As mine manager, Holtermann was at once noticed, and, realising the geological and historic importance of the find, gave immediate instructions that the specimen was to be brought out intact.

This was, of course, easier said than done. The mass had to be separated from the matrix; it was both heavy and fragile and had to be manipulated in the dark and confined space of the shaft. Then, when it reached daylight, it had somehow to be carried to the top of the steep ridge. Ore was normally broken up into pack-horse loads, but this piece had to be precariously manhandled, resting on six crowbars, carried by twelve miners, before it reached the doubtful safety of the dray which awaited it.

Merlin's panorama of the western slopes of Hawkins Hill, showing the line of reef; the Star of Hope is the fourth building on the right.

Measurements were soon taken. The specimen was four feet nine inches high, two feet two inches wide, and averaged four inches in thickness. It weighed 630 lbs. but the weight was not all gold, for it was veined with slate and quartz - the actual gold content was estimated as being in excess of 3,000 ounces.

There is a story to the effect that Holtermann endeavoured to purchase the specimen, but the matter is not mentioned in the company's letter-books. He had always possessed some faith in minor talismans, but, now, here was a major one which would carry him forward to all that the world had to offer. Indeed he may not even have tried, for on a previous occasion when he had wished to buy rich specimens, he had been fobbed of by the Board - mining companies were exceedingly touchy where gold specimens were concerned.

In the end the great treasure, along with other good specimens and high-grade quartz, went as routine to the stampers of Pullen and Rawsthorne in Church Street. The crushing was booked for the first week of November and by the 9th the result was officially announced as 15,581 ounces of gold from 72 tons of stone - the record which had been anticipated. A few weeks later, the shareholders received back about three-quarters of the capital they had invested.

To record the monster's brief but exciting existence some photographs had been taken. There was one by Merlin depicting it in proud isolation, a picture which was later used by Bayliss when he was assembling the montage on which Holtermann's stained glass window was based. Another photograph taken by the early photographic partnership of Beavis Bros., whose operator must have arrived post haste from Bathurst, showed the specimen surrounded by members of the syndicate and others.

The stained-glass window in the tower of Holtermann's house, now in the archive of the Sydney Church of England Grammar School. Photograph : J. C. Young.

Although Holtermann neither found, nor at any time owned the 'monster' it was noted in the company records as 'Holtermann's Nugget', presumably for simplicity of reference. Little matters such as discovery or ownership did not prevent Holtermann from associating his name with the discovery for the rest of his life. He advertised his later commercial ventures with a woodcut or lithograph showing himself standing beside the 'nugget', based on a montage made by Charles Bayliss a year or so later.

Meanwhile Beaufoy Merlin and his camera crew had returned from Gulgong and had recommenced work at Hill End, Ending plenty of business, for the settlement had substantially increased both in population and commercial activity. Several of the photographs taken at this time show Holtermann prominently included.16 As the late Jack Cato commented to the author : 'ln the great days of the gold rushes, many a photographer must have quitted his studio and darkroom to join in the tumult of the search, but surely Holtermann must have been the only gold miner to have neglected his mining to follow the camera.'

The photographer would now be working on his plans for Holtermann's great International Travelling Exposition, which was to consist of an extensive display of photographs, examples of raw materials, natural produce, prepared zoological specimens, and models of the machinery. Merlin's imaginative conception was far ahead of its time but the idea fell on welcome ears. Holtermann had long wished to do something for his adopted country and Merlin, whose health might have been already failing, 'must have had the ambition to achieve something more rewarding and more important than his house-to-house work.

The Exposition was announced with considerable wealth of detail in the press in early January 1873, and with the New Year, Merlin commenced work as Photographer to Holtermann's Exposition.

During the summer, Holtermann was the subject of a number of personal attacks in the Hill End and Tambaroora Times, stimulated no doubt by persons whom he had publicly held responsible for the effigy burning episode. This was an age of venomous gossip and malicious innuendo, and Holtermann was even castigated as a publicity seeker because of his charitable donations listed in the newspapers - this at a time when even half-crown donations were acknowledged. No doubt partly as a vehicle for reply, he purchased an interest in the new paper, the Hill End Observer and Tambaroora Herald17 but unfortunately no copies have survived for scrutiny.

Two decades of enquiry have failed to disclose any particular action on the part of Holtermann which could be considered as harmful to another person. One exception might be mentioned - and this is his failure ever to acknowledge his great debt to Hammond. It must have been very galling to Holtermann to have a new arrival come, uninvited, into the claim upon which he had toiled for so many years, and, defying him, easily find a rich series of veins. (Incidentally Hammond's diaries do not include any reference to what action he proposed to take had he been wrong about the veins to the west.)

The malice against Holtermann seems to have arisen only from the fact that he was different — a man of ideas backed by indefatigable driving force. To be different is ever to arouse suspicion, but to be different and wealthy is insuperable. When 'as a substantial donor (£150)' he was invited to speak at the laying of the foundation bricks, on New Year's Day 1873, of the new and long-overdue public hospital,18 he took advantage of the opportunity to express his principles

'... he did not intend to squander his hard earnings away. He was ready to help anyone deserving of aid; he had done so, and would do so again wherever merit called for consideration. Having accumulated a fortune, he proposed devoting a percentage of his income towards charitable institutions, and of all charities none could excel in their usefulness (as a hospital.) He deprecated the practice of persons leaving the country with all the wealth they had amassed; he intended to do differently; he meant to contribute to the institutions of the colony which had supplied him with his wealth . . .19

Shortly afterwards the shares in Krohmann's and Beyers and Holtermann's (then standing at 72/73 shillings) were the subject of a strong 'bear' selling attack. The shares recovered fairly quickly to 60/- and 62/6. 'Bears' were again active at the end of March when the shares were forced down to 49/- and even a few at 35/-. Some ground was recovered, but by mid-April the market had settled down at 35/- or less than half the figure of six months before.

An event of note was the visit of the new State Governor, Sir Hercules Robinson, and Party on 11 March, this including the Hon. G. A. Lloyd (Colonial Treasurer), Captain St John (Aide-do-camp) and Mr H. de Robeck (Private Secretary). On the next day, His Excellency inspected the 'new public buildings' (the Hospital, Church of England, and Public School presumably), and fired a shot at Krohmann's which happily disclosed much rich gold.

At the official dinner that evening at Coyle's Club House Hotel, with J. W. Lees,20 P.M. in the chair, Sir Hercules delivered one of those forthright speeches for which he was well known, with special emphasis on the appalling discomfort the party had soldered during the coach trip from Bathurst. The Hon. G. A. Lloyd also spoke — 'he believed the sun shone on no more loyal people in the universe than the inhabitants of Hill End. Here in the remote district of Hill End, amongst those vast mountain passes, a reception had been given to H.E. which excelled anything he had witnessed elsewhere (great cheers). The masons, the children, the arches, the mottoes, the banners, the shouts and that dinner were indicative of an attachment which could not be doubted ...'21

About June Holtermann resigned his managership at the Star of Hope Co., and turned his initiative towards the Mullion, a reef to the north of Orange. Here, for more than a decade, attempts had been made with inefficient equipment to tap the deep leads which were believed to exist in the area. Several shafts were sunk in an endeavour to avoid an underground stream, but on all occasions the water burst forth with tremendous force. Holtermann believed that if pumps of sufficient power were installed, the mine could be kept dry. Accordingly a new engine and pump were obtained and christened in front of a large party with the nome Holtermann's Enterprise. (After which there was eating and drinking galore, for which Mr Holtermann had provided on a grand sca1e.'22

But the new powerful pumps achieved little more than the old ones and, after a few further attempts in the following year, he gave up the unequal struggle against the forces of nature. The Mullion was to be his last major practical activity in gold-mining.

By mid-April Merlin had reached Orange, after paying visits to such places as Bathurst, Rockley and Montefores. On 24 April the Sydney Morning Herald's Travelling Correspondent reported : 'When on my road, close to Orange, I met the equipage of Mr Beaufoy Merlin, the photographer and collector for Holtermann's intended Grand Exhibition. Mr Merlin is sparing nothing, time nor pains, taking views of all the places of interest throughout the districts he travels and obtaining specimens of the various industries en route.'

Merlin's tour of the central west concluded at Dubbo and he returned via Carcoar and Goulburn, to Sydney in late July or early August. An intensive coverage of Sydney followed, totalling I80 exposures, concluding with several of Randwick Racecourse. The most attractive of the Sydney series are those around Circular Quay, showing numerous sailing ships at the wharves - the presence of some of these ships making it possible to date the photography accurately.

With the exception of a posthumous press article, this fine series was Beaufoy Merlin's last work. He died on 27 September 1873, at the comparatively early age of forty-three. Holtermann had lost a good friend, but the photography for the Great Exposition was to be continued by Charles Bayliss, who had long been Merlin's assistant.

Holtermann was now losing interest in Hill End. No wonder, for gold production was falling rapidly. From the 'nugget' year of 1872, the Annual Gold Escort returns from Tambaroora (which included Hill End) fell quickly : 80,592 ounces, then 62,834 ounces, then 25,266 ounces in 1874. By 1879, the returns no longer amounted to five figures. It was the end of a great epoch.

Soon Holtermann would no longer to be seen around the settlement, an unmistakable figure in his American-style buggy turn-out, ( complete with a pair of smart dapple-greys driven by his Oriental groom, Ashod; no longer would he be seen with resplendent sash at functions organised by the Manchester Unity Independent Order of Oddfellows, Lodge No. 47, Loyal United Miners. His thoughts had turned to Sydney, where his wife and daughter Sophia were already installed. His second daughter Esther, was born at St Leonards on 27 January, 1873.

In Sydney he would erect a gentlemen's residence on a grand scale to reflect his material success. It would have twenty principal rooms, with ceilings fourteen feet high. There would be supporting offices in keeping - and there was to be a tower. Of course, many a successful gentleman's home had a tower, but his would be different. He had purchased a suitable block of land on the heights of North Sydney (then St Leonards) and the tower was completed in the spring of 1874,

The tower was almost ninety feet high, commanding a magnificent view in all directions - the Harbour, Botany Bay, and the Blue Mountains thirty miles to the west -and its staircase was adorned with a circular window in stained glass depicting the wealthy prospector and his giant specimen. For the year 1874, there is still extant Holtermann's own Lett's No. 9 Octavo Diary23 bound in green cloth with both blind and gold embossing.

Treasure indeed : while most of the earlier papers had been written to impress the public, the Diary was a private matter. Here are found a host of business transactions, details of state and interstate trips, opinions of people he either knew personally or by repute. As master of a great house, he had much to do with the hiring of staff, most of whom proved far from satisfactory and the labour turnover tended to be rapid. The entries are regrettably spasmodic with considerable variation of detail and there are entries for only about half the pages. But one would hope for the Diary's eventual publication if only for the thread of conscious and unconscious clamour. Business matters are paramount, but there are occasional references to family outings, such as the note for the Easter Race Meeting on 6 April when 'plenty of people looked at Mrs B.O.H.' (Family life is more in evidence in numerous photographs in the Collection of distinctly Amateur type showing picnics in the bush and children's parties at home.)

Apart from its general interest, the Diary contains a varied amount of welcome information. It tells us when he placed the first order for the little marked bottles which were to contain his trusted remedy, 'B.O.H. Australian Life Drops', of which more later; the date when the last stone boring (turning) was placed on the tower; the names of his two grooms (Ashod from Singapore) and Fred Grunway (an Aboriginal). Notable omissions were anything about the stained glass window or any definite locations of his various North Shore properties.

But the most important omission is the absence of any reference to the ordering of the great lens for the huge panoramas. The lens - in fact there were several lenses of varying focal lengths — would have come from France or Germany. The calculation, manufacture, correction and transport of such a lens would have taken at least a year. Holtermann had also obtained for Bayliss a new cameral: of format 18'' by 22'', this being the full size of a sheet of albumen printing paper.

Now was revealed the unprecedented purpose of the high tower - it was expressly designed as a camera support - the world's tallest 'tripod' for the world's largest camera. And with that giant camera Holtermann would take giant photographs, bigger than had ever been seen or even thought possible. He would take them to Philadelphia for the 1876 Exhibition, where he would gain first award for photography - and of greater importance, he would show the millions of visitors the glory without equal of Sydney's magnificent Harbour.

By the late winter of 1875, everything was ready - lens, chemicals, sheets of plate glass - for the attempt. The word 'attempt' is used advisedly, for it is most unlikely that anyone in the world had ever attempted the hand-coating of a sheet of plate glass measuring more than three feet by five feet and weighing fifty or sixty pounds. Now Holtermann and Bayliss were to achieve this, not under controlled conditions in some form of laboratory but in a temporary wooden room25 constructed above the tower that was camera and darkroom combined. And after each exposure and processing stage, a huge plate had to be manhandled down several flights of narrow tower staircase to a room set ready with a fire for drying and equipment for varnishing. Varnishing is essential for the preservation of any collodion plate and even this anal stage cannot be considered simple, for the wet-plate coating has little or no adherence to its glass support.26

The stupendous enterprise is outlined in the holograph and so is its cost, recorded as £1,000, and there are references to failures and practical difficulties. The giant panorama was in three sections - two negatives 3'2"' by 5'3'', covering Garden Island to Miller's Point and one of 3'2"' by 4' for Miller's Point to Long Nose Point.

Many other panoramas were taken in different sizes, the most important of which was on 18" by 22" negatives; when this series was joined up, the ensuing panoramic view measured thirty-three feet. This panorama, and some smaller versions measuring five feet and three feet respectively were sold extensively as Holtermann's Views.

photo-web special 2008 note:

an exceptional copy of this panorama is in the National Gallery of Australia's collection

Thus it was that Holtermann and his technician made photographic history. In Australia, far from the great centres of progress and invention, they had successfully produced the world's largest negatives. The claim was accepted locally with some doubt for the populace had long been conditioned to the acceptance of the idea that everything that was newest and biggest in the world must necessarily happen in the brash young United States. The matter was loyally settled by the Sydney Evening News of 22 October 1875:

'Mr B. 0. Holtermann, the well-known gold-miner, and one of the richest men in the colony, claims to have produced the largest photographic views in the world. This is, of course, saying a great deal. Our Yankee friends who are proverbial for big things, may possibly be inclined to dispute Australia's claims to photographic superiority . . . Apart from the size of the pictures, they are splendid specimens of the photographer's art, the outlines being sharp and clear, and the various objects shown coming out prominently before the eye.

The difficulty of producing pictures of such size can best be understood and appreciated by photographers, among many of whom, we understand, it is believed that it is not possible to execute photographs of such magnitude. If such a belief exists, Mr Holtermann claims to have dispelled it, and to have worked a revolution in the art of photography . . . the whole of the perspective is shown much clearer than can be seen with the the naked eye.

Signboards between two and three miles off can be seen easily without the aid of a glass . . . These views are the principal ones; but Mr Holtermann's studio is stocked with thousands of photographic views, all splendid works of art of different parts of New South Wales and Victoria. It is his intention to start for England early next year with his grand panorama, his principal object being to induce Immigrants to Come to Australia.

It was thus made clear that it was not only Australia that Holtermann wished to impress but the great world overseas, which knew so little of the achievements and potential of his adopted country. And if any notice was ever to be taken of Australia, it would have to be at the forthcoming Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, planned to celebrate the Declaration of Independence and the first of the modern international Exhibitions, and at the Paris Exposition Universale Internationals de 1878.

For Holtermann the year 1876 was an exceedingly busy one. First of all, as he was to be abroad for several years, he had to appoint a manager to control his various mining and land enterprises during his absence and for this position he nominated William James Slack, whom he had known as a hotel-keeper and postmaster at Hill End. Holtermann arranged to take with him a series of the photographs mounted on a great roll of canvas - measuring 5' by 80' - which could be unrolled and its contents described during his public talks. He also took with him one or more of the giant plates by way of visual proof of his tour-de-force.

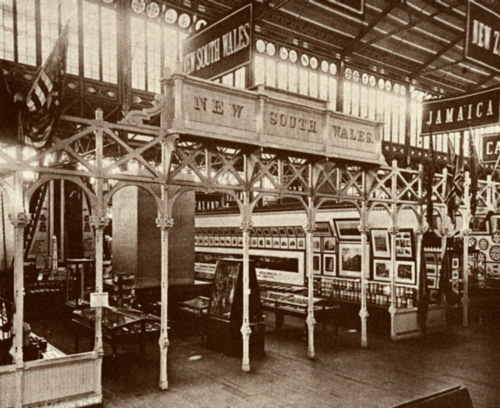

A large number of Merlin's and Bayliss's pictures, including the panorama, appear to have been accepted by the New South Wales Government for display in its official stand at the Exhibition. A contemporary illustration shows that a large number were used and were well displayed around the walls. Sailing day for the City of San Francisco (3,000 tons, Captain Waddell), bound across the Pacific for the city of that name, was 2 June.

Aboard, amongst the passengers listed, were 'Mr. and Mrs Bernard Otto Holtermann, the Misses Sophia and Harriet Esther Holtermann and Miss Emmett' (a sister-in-law). San Francisco was reached in early July and Holtermann lost no time in contacting the city's photographic society.

The occasion was reported in the local press and reprinted in the Sydney Evening News for 1 September:

'The Photographic Society of the Pacific Coast held a regular monthly meeting last evening in the galleries of Messrs Bradley & Ralston, Montgomery Street, San Francisco. Mr Ralston proposed the name of Mr B. 0. Holtermann, of Australia, for membership. Mr Ralston offered the following resolution: 'That as photographers we are indebted to the liberality of B. 0. Holtermann for demonstrating the possibility and perfecting the production of the largest negative, and we tender him our thanks of this Society for kindly placing the negative on view for inspection.

'Mr B. 0. Holtermann, responding to the resolution on his behalf, begged the Society to accept his sincere thanks for the reception he had received in San Francisco by the fellow members of his profession.'

From San Francisco, the family (and the precious photographs) hastened by rail eastward across the great continent. But when the train reached the city of Burlington, on the right bank of the Mississippi River, about two hundred miles from Chicago, a stop-over was necessary, and fully explained in the columns of the Burlington Hawk Eye of 25 July 1876:

'There was a native Australian born in Burlington yesterday . . . B. 0. Holtermann, a resident of Sydney, Australia, and member of an extensive arm, Holtermann & Company, of that place, is on his way with his wife and daughters and a servant to Hamburg, Germany. Careful of the comfort of his family, he chose the shortest and safest route across the continent, which is well known to be the C. B. & Q. (chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad) and Holtermann, after changing his through checks for his baggage for depot checks, sought and obtained commodious and comfortable quarters at the Barrett House, where, in Room Number 39, within two hours, a son was born unto him whom he would do well to christen Burlington.'

It was typical of Holtermann that he should have accepted the Hawk Eye's suggestion, and the son was duly christened Burlington Otto Holtermann went even further-the second and third sons were also geographically named: Sydney and Leonard (St Leonards). Burlington was to die on 27 June 1897, just before his twenty-first birthday.27

As soon as Mrs Holtermann and young Burlington were able to travel, the party continued on to its destination, Philadelphia. When the awards at the centennial were announced, Holtermann's photographic exhibit received the honour of a Bronze Medal - a recognition of high order, since there were no medals in silver.

Holtermann's exhibit of New South Wales photographs on display at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876. By courtesy: Free Library of Philadelphia.

It is impossible for people of the present generation, familiar since childhood with the world's great inventions from many nations, to appreciate the glamour and public appeal of the great international exhibitions of last century. Nearly ten million visitors passed through the turnstiles during the I59 days the Philadelphia Centennial was open, while the maximum attendance for any one day was 274,919. Presumably a substantial percentage of these visitors would have seen the New South Wales Court with the Holtermann panorama and its scores of supporting photographs and returned home knowing rather more about the place than they had previously.

The party also made several inspections of the American and various international exhibits. Holtermann visited the American Typewriter Company display where he was presented with a neatly typed error-free copy, entirely in capitals, of John Greenleaf Whittier's 'Centennial Hymn' as sung at the Exhibition opening. This sheet was preserved among his souvenirs - an excellent example of early machine work.

Of Holtermann's European stay, it is only possible to generalise. Later, in his parliamentary days he spoke of his tour of Germany, France and Switzerland, lecturing and explaining his photographic exhibit. Hamburg was reached in the early autumn of 1876 and some time would have been spent visiting relatives and friends whom he had not seen for almost twenty years. It must have been pleasant to return to his homeland a successful man, to display his roll of photographs with a real sense of achievement, and to speak with conviction of all that eastern Australia had to offer.

He spent some time considering suitable agencies for his importing business and some of these will be mentioned later. His name appears in the Sand's Directory for 1877, the entry which would have been arranged before he left Sydney reading 'Commission Agent, 42 Pitt Street'.

The party left Germany for England in December 1877. The next date of importance relates to his success at the great Paris Exposition Universelle Internationals de 1878, where his photographs were awarded a Silver Medal.

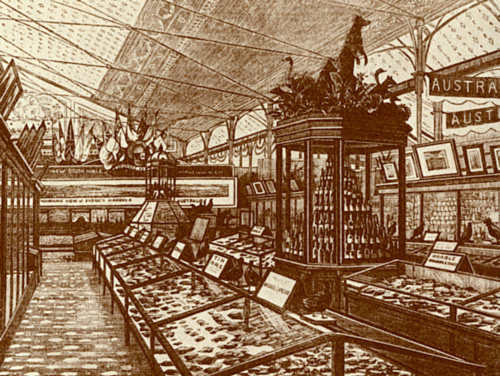

Holtermann's panorama of Sydney on display at to Paris Exposition Universelle Internationals de 1878. Australian Town and Country Journal, 27July 1878.

Back in Australia he demonstrated his belief in press advertising by numerous displays, especially those for his principal agency, the Davis Vertical Feed Sewing Machine, a held in which he had several energetic competitors. He advertised, continuously, the merits of his Holtermann Life Drops, a herbal remedy compounded from a formula which, as a young man, he had received from a doctor in Germany, usually with an illustration of himself standing beside the 'nugget'. One copy only survives of his most striking display - and that, happily enough, is in the Royal Hotel, Hill End, where . it has long been a tourist attraction.

Holtermann is also reported to have been the first to import German lager beer on a considerable scale and this is supported by the preservation amongst his papers of a bottle label which reads : 'Brauerei zum Bayerischen Lower Lager-Beer, special (sic) prepared and imported for the Australian Colonies.' In addition Holtermann had many other agencies which he handled from his handsome new four-storey building at 674 George Street. 28

A picnic at Middle Harbour soon after the Holtermann family's return to Sydney from Europe in 1878. In the foreground Holtermann holding Esther (left) and Burlington; Mrs Holtermann is behind her husband to the left; the eldest daughter Sophia seated on the far left; the other members of the party have not been identified. (Photographed with Holtermann's Attewill stereo camera by a member of the party.)

The Sydney International Exhibition of :879 was staged in the 'Garden Palace'. It is pleasant to note that an entire bay was devoted to a Holtermann photographic collection, with acknowledgement to Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bay1iss.29 Holtermann's interest in photography continued as a pioneer wet-plate Amateur. In 1881 he personally photographed a panorama of Sydney on I0'' by 22'' plates, perhaps because the previous series proved too large for ready sale.

He purchased a stereo camera for taking stereoscopic pairs — this an 1878 model by Attewill and Company of London, with a pair of Ross Lenses.30 In various formats, he recorded sundry travels, family picnics, birthday celebrations and scenes around the home — some at the 'tower' house, some at his new home, St Leonard's Lodge in West Street, between the present Myrtle and Burlington Streets, to the west of St Leonards Park. Its principal function completed, the 'tower' house in Union Street was leased and later sold.31 In 1880 he was living in William Street until the family moved permanently to the Lodge.

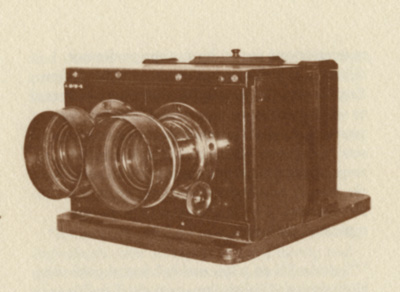

Holtermann's stereoscopic camera, an 1878 model by Attewill & Company, London. By courtesy : Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney.

In the same year Holtermann's thoughts turned definitely to an earlier dream of becoming a Member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly. Accordingly he was nominated for the coming election for the district of St Leonards, but it was something of a vain hope, for the sitting Member was the Secretary for Lands, James Squire Farnell, who had represented the area for six years and was unlikely to be unseated.

However, Farnell, or one of his campaigners, saw fit to issue an extraordinary anti-Holtermann handbill, apparently considering his rival worthy of shot and shell. It was a period when a regular feature of vaudeville entertainment was to have some performer deliver songs and recitations in a weird broken English that German immigrants were supposed to speak. Holtermnnn preserved amongst his papers a copy of the handbill containing two sets of doggerel verses in this style headed respectively Oration at the Bar (pub.) and On the Stump, purporting to be written by Holtermann.

The last lines of the verse are typical of the whole:

' "dinky 1'll go a law makin'' out shpoke der Holtermann, "Foost ding, now dat I builds mine house I doos all vat I can, Vor pridges and goot roads, und dings to goom to my nice place, Dat's vot 1'll do so soon I vins dis here law-makin' race;

"und if der Farnell has de sass to geom und vight mit me, 1'll deach him dricks from Vaderlandt,'' says Holtermann, says he.'

As might have been anticipated, Farrell was re-elected.

Two years later Holtermnnn campaigned again. Farnell had departed for New England, and the population of the St Leonards district had grown to such an extent that the electors were now required to choose two representatives from the seven who were nominated. The advertising pages of the Sydney Morning Herald of 5 December 1882 carried Holtermann's campaign manifesto. It was attractively displayed, occupying about nine inches and ran as follows:

‘Electors of St Leonards. Vote for Holtermann who will give his best attention to your requirements . . . whose interests are identical with your own . . . a man of indomitable energy and perseverance . . . who, through weal or wale, has proved the staunch friend of the working man . . who has the courage to demand that your rights be accorded to you. Vote for Holtermann, and a hrm adherence to the Education Act. Vote for Holtermann, who maintains your rights to the privileges of local opinion. Vote for Holtermann, and a judicious but not indiscriminate, immigration. Vote for Holtermann, and free trade, free trade, free trade. Vote for Holurmann, who for the past ten years has given his earnest support to every public movement having for its object the advancement of your electorate. Holtermann and Progress. Holtermann and Local Improvements. Holtermann and Fearless Representation. Holtermann for St Leonards.'

On this occasion, he was not only successful but led the field. The results read: 'Mr B. 0. Holtermnnn, 965 votes; Mr G. R. Dibbs, 962 votes.' Both names were marked with a printer's dagger, indicating that they were composed to the land policy of the present government as embodied in their Land Bill'.

Whilst Holtermnnn was in the House, he delivered three long addresses and a number of shorter replies. The first address, on 4 March 1883, was in support of a motion for the establishment of a government-operated steam-ferry service to the North Shore. The Amount in question was the somewhat extravagant one of £40,000. Even so, the motion was narrowly lost by 24 votes to 17 'as such service would enter into direct competition with a similar service successfully established and satisfactorily worked by private enterprise'.

Holtermann's second speech was delivered on 10 April 1883 in support of his own motion to the elect that 'the sum of £25,000 should be apportioned out of the sum of £150,000 . . . for immigration generally, for the introduction into this colony of German immigrants, to embark direct from Hamburg . . .'

His speech was long and sensible. He pointed out that while more than I60,000 Germans went to the United States during the preceding year, only 883 come to Australia, since it was comparatively easy and inexpensive to go to America and exactly the opposite to come to Australia, because of the absence of any direct shipping line. However the regulations at the time allowed only ten percent expenditure on behalf of 'foreign' migrants. Mr Garrett asked 'How do we know that we shall not get the scum of the towns, the dangerous elements of the population?

His motion was lost by 31 votes to 21 . The 'no' voters included Farnell and Sir Henry Parkes.

On the same day, he put forward another motion suggesting a supplementary estimate for the present year 'not exceeding £20,000 for the purpose of procuring photographs of Sydney (in panornma), its public buildings, streets and other architecture, also of the most important public buildings and public works throughout the colony, and distributing the same amongst the various art galleries, mechanics' institutes, and institutions of a like character throughout Europe, with a view of thereby exciting the attention of the most desirable class of immigrants and others to the advantages overed for the introduction of skilled labour into this country.

Holtermann put up an excellent case. He referred to the successful showing of his own Exhibition in America, France, Germany and Switzerland and said that:

'He had in his possession many newspapers containing eulogistic comments upon them . . . When he had showed his pictures in Hamburg, Paris and Berlin, the people were astonished to find that the Australian cities had made so much progress, and that they contained so many fine streets and buildings. Some fifty or sixty immigrants now in this country had been induced to come out to Australia to a great extent in consequence of having seen his photographs, and because of the information with which he had supplied them.'

Holtermnnn went on to mention two specific individuals: one an expert in the painting and decorating of railway carriages, and the other a metallurgist dwell versed in the extraction of metals from minerals . . . The metal he was trying to introduce was phosphor bronze, which did not heat on any extent of journey, and lasted longer than any other metal . . . its use in our railway engines would save £5,000 to £10,000 yearly by doing away with the necessity for repairs.'

But Holtermann's idea of encouraging migration by means of photography, was still more than half a century ahead of parliamentary acceptance. The rest of the story may be read in Hansard. One John McElhone, a Member for West Sydney, scorned out of hand the idea of phosphor bronze being of any value and went on to propose an alternative motion: "That this sum of £2,000 be divided in equal proportions, one half to be spent in photographs and the other half in Holtermann Life Drops. It would immortalize the Hon. Member if the amendment were carried.' Another Member, George R. Dibbs (also for West Sydney), drew attention to the fact that £500 had been voted to 'meet the cost of photographs of public works and buildings in the city and colony generally'. It is a fact that the large number of photographs were taken by official government photographers of the time, but the majority of these pictures served no more useful purpose than the decoration of railway refreshment and waiting rooms.

Rebuffed, Holtermann withdrew his motion.

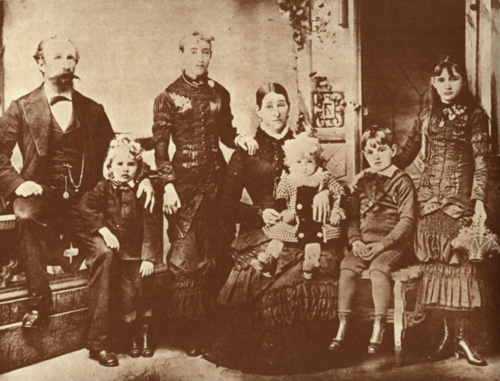

The Holtermann family taken just before Holtermann's death in 1885. (left to right) Bernard Otto Holtermann, Sydney, Sophia, Mrs Holtermann, Leonard, Burlington and Esther. (studio photograph, private collection.)

One of the last occasions on which Holtermann addressed the House was towards the end of 1884 when he drew attention to a 'diabolical outrage' committed on the previous evening against three valuable horses And stated that 'it behoved the Government to offer a reward for the discovery of the perpetrator or perpetrators'.

He lived in a period of utter dependence upon the horse, and during the last decade of his life owned at least one carriage pair. Apart from horses, there is photographic evidence that Holtermann had a small menagerie which included emus and wallabies.

He was still a parliamentary representative at the time of his death. He actively supported any move associated with the progress of the North Shore: his nome has been linked with the building of the North Sydney Post Once and Courthouse, the laying of the tramway from Milson's Point and the extension of the railway line south from St Leonards. He even offered to contribute £5,000 towards the cost of building a bridge across the Harbour.

In his latter years he renewed his interest in unorthodox medicine and became President of the Australian Medical and Surgical Infirmary. The 'Infirmary' consisted of consulting rooms only, these being presided over by their Physician-in-chief Dr Elton Boyd.

Bernard Otto Holtermann died on 29 April, 1885,32 his forty-seventh birthday.

His medical attendant, Dr C. Yorke, gave as the causes of death, scarcer of the stomach, cirrhosis of the liver and dropsy' and recorded that he had been consulted about the complaints over the previous eighteen months. The long illness must have been chastening to a man of so many ideas and with such a passion for activity.

He left behind him a wife and five chi1dren,33 the youngest, Leonard, being only two years old. The family was, of course, well provided for as Holtermann's estate at the time of his death was valued at £54,000.

But it could be said that Holtermann died a fulfilled man. He had gone into the unknown and found gold in that place with the magic sounding name. He had repaid, in considerable measure, his adopted land for the many favours it had bestowed upon him. Most important of all, he had attained the greatest wish of his life, that of sitting as an elected member of a British parliamentary body. And as Jack Cato truly wrote:34 'Bernard Otto Holtermann can be ranked, perhaps, as Australia's first and greatest amateur of photography, using that word in its original French sense. He liked the art for its own sake, yet realized, perhaps, more than he knew, its great documentary possibilities.'

>> see also A. P-R. 1953

Footnotes

-

Yet, strangely, amongst the very few diaries and memoirs there was one which included passages relative to Hill End in this period - see Mark John Hammond diaries and transcripts, Bibliography.

-

Holtermann Papers, Mitchell Library, Mss 968.

-

Bernhardt (angl. Bernard) Otto Holtermanm son of John Henry (angl.) Holtermnnn and Anna Nachtigall. The father was a wholesale fish merchant.

-

The brother already in Australia was Francois Auguste Holtermann. He is mentioned several times in the holograph and also officially as being at Root Hog-or-Die (a settlement on the Macquarie River, a little upstream from its junction with the Turon) as early as 1865 and at Hill End in May 1872, but there seem to be no later references.

-

Muller's Homburg Hotel, then at 108 King Street E. He catered for German patronage by advertising : 'Deutsche Gasthaus, Deutsche Kinche.'

-

Fairfield, on the Clarence River near Drake, was better known as the 'Timbarra Rush'.

-

Ludwig Hugo Louis Beyers, 184? — 1910 born in Posen, Poland. After education at a denominational school, he come as a youth to Sydney. Here, after a short period at the drapery counter, he was 'stricken with gold fever' and leaving 'the yard stick and the counter' joined in several contemporary rushes. He appears to have been recruiting his health at the Hamburg during the summer of 1858-9. He located the reef which was to bear his nome in 1860-61 . It could have been his faith in this reef that led him to leave Hill End for extended periods prospecting other fields in order to maintain the claim; one of these absences was unfortunately during October 1872 when the great specimen was photographed, for his place beside the mass of gold was occupied by Alfred Bullock (the underground mine manager) who was his representative. On 22 February 1865, he married Mary Emmett, of White Rock, Bathurst. There were six children: Sylvia Helena (1868), Gertrude Harriett (1878), Oswald Arthur (1872),Letitia Mary (1874), Clara Victoria (1876), and Billvenah Clarinda (1881), all of whom were born at Hill End, where Beyers's cottage is still standing. His tastes were simple and all he asked of life was to live quietly amongst his friends. However this was not to be, for he was induced to enter politics, becoming M.L.A. for the Western Goldselds (1877-80) and for Mudgee (1880-82). About twelve or fifteen years later, he joined in the W.A. gold rush, but met with little success dying at Mt Morgan on 28 May 1910. The most reliable short biography will be found in The Hill End Story, Book 1. There is an entry in Australian Men of Mark, vol. II, ser. 2, Sydney 1889, but this contains a variety of inaccuracies.

-

The settlement was originally reported on 3 June 1859 by John A. H. Price, as an unsurveyed area of about thirty acres containing thirty or forty houses, known locally as Bald Hills. It did not optimally become Hill End (sometimes Hillend) until 28 March 1862. The name Tambaroora was often applied to the whole area.

-

Harold Walpole Archives.

-

Holtermann Papers.

-

The Marriage Registry entry shows that Mary Emmett was under age. Harriett was born 16 February 1846, died 7 July 1903.

-

Mark John Hammond was born 15 November 1844, died 4 February 1908 ; Alderman and later Mayor of the Borough of Ashfeld, afterwards Member for Canterbury in the Legislative Assembly 1884-7.

-

Krohmann's was one of the richest claims on Hawkins Hill. When floated into a company,

it returned the entire capital within nine months. Holtermann had early purchased a small share (believed to be one-eighth) and benefited when some. of the rich strikes were made.

-

In The Hill End Story (Book 1), there is a calculation to the effect that, during the years 1871-3, companies were floated with capital totalling £3,510,000. The gold actually won from the ground in these years would be worth little more than one-fifth of this sum. The vast majority of claims were utterly without prospects, while, as for the promising ones, it was soon found that the richer veins were those closest to the surface and from these in many instances the worthwhile gold had already been extracted.

-

The Hill End and Tambaroora Times: was established 5 April 1871 and ceased publication during October 1875. Only six copies now survive. Its proprietors were Richard Lee and Michael Sheppard.

-

The two best are the photographs of Jenkyns's forge in Clarke Street, and Bray's Pharmacy in Tnmbaroora Street near Short Street (plates 58/53). The pharmacy was situated in a block of shops which Holtermann had built during the winter.

-

The Hill End Observer and Tambaroora Herald was established on 17 April 1872 and ceased publication on 3 October 1874.

-

Its proprietor was Edward C. Wilton and the first editor Frederick Humphries.The public hospital, after substantial restoration, is now the Hill End Visitor Centre and Historical Museum of the National Parks and Wildlife Service.

-

Hill End Observer and Tambaroora Herald. Only a few clippings have survived.

-

His Excellency kept a careful record of his speeches and eventually published a selection in a volume entitled Speeches by H. E., etc., Sydney 1879 (F 14999).

-

Sydney Morning Herald, 24 March 1873.

-

Australian Fool and Country Journal, 6 December 1873.

-

Privately held.

-

This camera was used by Bayliss in April 1874 to record Holtermarm's purchase of the Post Office Hotel and in August 1875 at the time of the funeral of Captain J. G. Goodenough, Commodore Commanding Australian Station, and for the Melbourne coverage.

-

Although the structure was a temporary one it must have been of exceedingly massive construction, strong enough to inhibit the slightest vibration. Images obtained by telephotography are particularly susceptible to lens or camera movement, but the giant plates show no sign of such a weakness. The room measured 10' by I2' and its mere installation was a major undertaking. The southern wall had to provide for a variety of firm positions for the lens. It is likely that the massive sandstone pinnacles were planned to serve as anchorages.

- When dry plates, i.e. those of gelatin emulsion type, became manufactured commercially, the glass was 'subbed', or coated with a substratum to ensure emulsion adherence.

-

My good friend and historian, the late H. J. Rumsey, told me that he well recalled playing football with Burlington. He also remembered seeing the great lens, which he said was about five inches in diameter. I am indebted to him for much information about the period; Amongst numerous other matters it was he who identified Bayliss's photograph of the landing of Commodore Goodenough's funeral cortège at Milson's Point.

-

For further details of Holtermann's Ulcerous agencies see Bulletin, 22 May 1880, p. 3.

-

The awards list in the official catalogue records 'B. 0. Holtermnnn, Large photograph of Sydney, well printed and joined, Commended, and Charles Bayliss, The Large View of Sydney is fairly executed, Commended.'

-

Now in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney.

-

The tower-house was rented in turn by tenants Saddington and Chisholm. On Holtermann's death, the property and its eight acres of grounds were purchased by Sir Thomas Dibbs, who later (in 1888)sold the building and some of the ground to the trustees of the Sydney Church of England Grammar School. Over the years there has been a considerable amount of rebuilding and alteration; some of the renovations, by coincidence, were designed by my brother-in-law, architect J. K. Shirley. In 1934 the tower's earlier-style ornamentation was removed and the whole refaced with modern brickwork, while the window apertures were bricked over to conform with the general scheme. The stained-glass window was removed to safe keeping in the school library.

-

Holtermann's death was registered by a brother, Herman Adolfe Holtermann, a dealer in butchers'

supplies.

-

Holtermann's children at the time of his death were Franzesca Sophia (I4 years), born at Hill End,

Harriett Esther (12), born at Susanne Street, St Leonards, Burlington (9), Sydney (5) and Leonard (2). The first-born son (Bernard H. J.) died at three weeks on 4 February 1875.

-

Personal communication.

continues: Merlin

Introduction / Processes / Holtermann / Merlin / Bayliss / Iconography / the Plates / Bibliography

>> see also A. P-R. 1953

The text and notes to the plates: copyright © Keast Burke 1973

The original GOLD AND SILVER plates were taken from the Holtermann negatives, Mitchell Library Sydney.