| Before you read my 1996 article below

you may like to read my 2023 comments about this piece on my blog - click here.

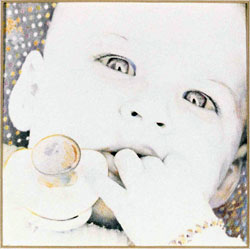

|  | #1 Micky Allan, The Family room

(Self Portrait) 1982 |

| | An online version of article originally published in Art and Australia, Volume 33, No 1. Spring 1996.

Photographs and images are mainly as in the original – there are a couple of replacements.

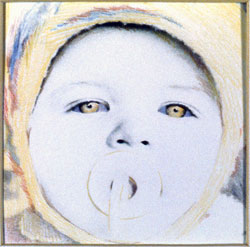

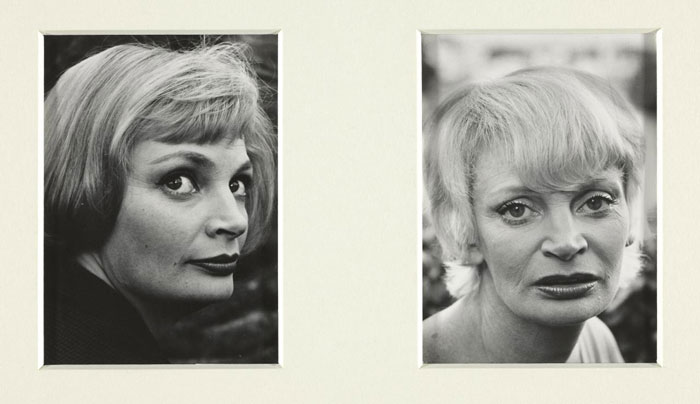

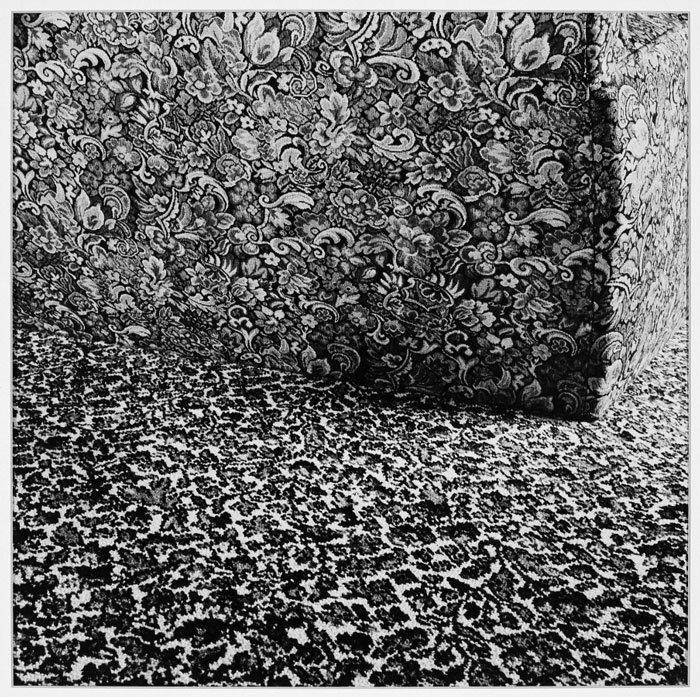

Short captions have been used with more details in the list at the bottom of the page. Tell me, will I always have to think of myself as a woman photographer, can’t I just be an artist? asked a young student at the 1995 International Women’s Day Photoforum at the National Gallery of Australia.1 ‘ When I looked at the waves of blonde hair streaming down her back onto her hippy-style skirt I was struck by a shaft of nostalgia for the fashions of my youth. As convener of the session, I was wearing, as were a number of the other women present that day, the artworld power dress of ultra-short hair and gender-neutral pants and shirt. I pondered on the contrast of styles and how soft-rounded femininity still jars with the popular image of the macho ‘derring-do’ photographer well-hung with cameras and long lenses. The student’s question was part protest, part prayer. She had been hearing from the established women artists that gender still matters not only in practical terms of equity in exhibitions, reviews, acquisitions and positions, but also in expectations as to subject and style. The artists she addressed that day were Micky Allan, Sue Ford, Sandy Edwards and Helen Grace, whose careers had begun in the 1960s and 1970s; Eugenia Raskopoulos represented a younger generation from the graduates of the 1980s. | I had convened the Photoforum to ask these artists what’s happening now for women in photography, about their own evolution and how changes in their work have been received. Sue Ford replied with some irony. ‘When I started in the sixties I wasn’t aware there were any women photographers. So, I haven’t had role models. It’s better for women now, but we still don’t get the reviews the men get, it doesn’t matter how senior we are. I’d like to escape all the labels you know, woman-photographer - now I guess it’s seventies vintage woman photographer!’  | | Eugenia Raskopoulos, when challenged about how she dealt with being labelled as a ‘Greek-Australian-Woman-Photographer’, pointed out that she is all those things by birth and by choice, but that ‘people don’t think of themselves with labels’. She sees herself as an artist; the categorical hierarchies come from others. Micky Allan’s response raised issues about subject matter and style, best expressed in her essay for the ‘Women at Watters’ exhibition (part of the National Women’s Art Exhibition program): 'I made a decision a few years ago not to hold back in any way from generating anything in my work that might issue from my femaleness. I don’t care how delicate, how soft, how subtle it becomes. Love, compassion, beauty, praise. In their clear form they are neither male nor female, but how far have we associated them really with ‘female’ and therefore ‘lesser’, and women also have thrown them off in reaction. | | #2 Sue Ford, Sue 1996 | In an art world that idealises toughness (rather than spiritedness), ugliness, shock, even anger and hatred, I see young art students struggle every day as they make these qualities internalised shoulds. The question that intrigues me now is: ‘What would women really paint (or perform or install or sculpt or write or curate) if they did it from their heart of hearts?'2 Allan’s essay also suggested that her early work had been seen from too narrow a view of feminism which disavowed a spiritual approach in favour of more specific social issues. Perhaps a few people in the audience stopped, even squirmed, for a moment, considering the challenge of how much they did anything from their heart of hearts. Her comments determined my own ‘incorrectness’ in including references to women's appearance in a serious art journal.  | |  | |  | | #3 Micky Allan, Babies 1976 | Allan and Ford were prominent among those artists in the 1970s who chose photography as an accessible, relevant and very contemporary medium. Works from this period tend to be interpreted fairly literally and are usually located within the context of the social alternatives of the ‘counter culture’ personal documentary style of photography and feminism.3 Since the early 1980s, Allan has disengaged with a dialogue between the graphic and the photographic and returned to painting. Her subject matter and style have become more abstract and metaphorical and centred on a celebration of spirituality and the philosophy of being.4 Part of the agenda for a Photoforum was my own interest in how we interpret the changes over twenty and thirty years in the work of artists such as Allan, whose work has undergone considerable apparent change in subject and treatment. In instances where change has been dramatic, that which has remained or been amplified, which has been left out or not pursued, throws the essence of the work into higher relief and calls for revised interpretations of earlier imagery. Before the 1990s there were precious few women photographers who could be studied over a long and continuous working period. Sue Ford’s perception that there weren't any women photographers in her early career was a reflection of the relative invisibility and rarity of photographers, male or female, within any fine arts context before the 1970s.5 The young woman photographer of today, along with the general public, has the luxury of a background of several strong generations of women artists who have worked with photography in a wide range of approaches. Any study of photography over the last decade will show that many artists have abandoned belief in a self-expression grounded in camera realism. In particular, graduates from the early 1980s onwards have opted instead for a clear avowal that the camera has no purchase on reality.6 The strategies of the 1980s associated with contemporary critiques are evidenced in overt studio staging and tableaux, enthusiasm for the grand scale of high art, a revelling in colour from sizzling kitsch to shades of the necropolis and, most seriously, a desire to connect with the imagery – and thus wider history – of western culture. During the 1980s a number of women photographers whose work began in the 1960s and 1970s have exhibited in different degrees comparable movements away from the documentary-representational forms adhering to the classical unities of time, space and action towards works using constructed imagery, assemblage and tableaux. 7 New works tend to revel in majestic scale, either physically or in subject matter, and weave in historical, philosophical, spiritual and cosmological references into which former feminist, personal and social flags are subsumed. Micky Allan’s paintings might seem to have little in common with the subjects of her earlier photo-based work. She established her reputation as an artist in the 1970s with series of works using handcolouring over black and white photographs. Small works such as the ‘Babies’ series, 1976, as well as her travelogues and Botany Bay Today series, were seen as engaging with their subjects in terms of social issues.  | |  | |  | | #4 Micky Allan, Botany Bay Today, 1980 |  | | #5 Micky Allan, Garden of the rolling horse I, 1984 | | |  | | #6 Micky Allan, Untitled 1984 | Her ‘pure’ paintings of recent years can be connected to the earliest works largely through formal elements of a particular palette of high key colours, acid pastels and intricate layering of line and washes. Allan has articulated her paintings of fantasy gardens as zones in which inner and outer realms of knowledge are explored. These concepts are also extended to her descriptions of the ‘Babies’ series in which colour strength is a key to the path from being to knowingness in babies between the ages of one year and six months (the latter has a red bow!). Handcolouring, which Allan more or less pioneered in the 1970s, was seen then as being a feminist strategy that subverted the dominant pure print fetish of mainstream art photography and also, by extension, the one-dimensional realities with which photo-naturalism colluded. The philosophical meaning of colour as a continuing essence and site of Allan’s work does not undo the past readings but rather enlarges our understanding of how she has developed her feminism. Similarly, Sue Ford, who also began with painting studies as well as photography (and has since worked across a number of media), has in recent years considerably enlarged the scale of her work and range of subject matter through use of multipage colour laser copiers to make large murals. These are a grid of enlargements from small collages often hand-painted in the first instance. Ford’s new scale, seen in her ‘From Van Diemen’s Land to Video Land’ exhibition of 1992-93 and her current shadow series, is quite consistent with her political and social concerns.8  | | #7 Sue Ford, Lynne, 1964 and 1974 |  | | #8 Sue Ford, Haunted, 1992 | Haunted, the fourth image in the Van Diemen’s Land suite, literally breaks up the image of a fair-to-all Australia and the Federation slogan of ‘One People’ by revealing ghosts in the national closet. Convict manacles seem to rise from the grave to knock at a national identity in which injustices and exclusions continue. The mirror imaging (which creates a curious Rorschach blot style female pelvis in the centre of the image) parallels the ways in which history repeats itself. The previously supportive statues of women appear to topple the bust of colonial patriarch William Clarke off his perch. Ford’s works have frequently visited issues of identity and self-image, especially as affected by time. Her early ‘Time’ and ‘My Faces’ series appeared to exemplify what the camera did best: recording. Other series negotiated or renegotiated genres such as fashion and advertising which set and reflect the image of women. Her use of friends – not professional models – made the images seem more playful as they were transparently very real people. Her new works range freely over the imagery of early Australian history and the personal photograph but continue her concerns with how identity is constructed through images. Fiona Hall presents perhaps the most dramatic case of a transformation by an artist whose early work was often seen within classic traditions of purist art photography.9 Her first studies were in painting, but by graduation in 1974 she had turned to photography exclusively. Her student works, such as the still life in which a flower-patterned chair and carpet merge, maintained taut relations between figure and ground, flat and illusionistic space. This type of work was born of a passion for the work of Henri Matisse and also relates to the formalist aesthetics of abstract art in the 1970s.  | | #9 Fiona Hall,Leura New South Wales, 1974 | By the early 1980s Hall was assembling objects of her own devising and photographing them in series of colour photographs that mimicked famous paintings. The element of whimsy and acute inventive ‘seeing’ evident in her earliest photographs also appeared in her later 1980s constructions, such as the sardine can cut-outs Paradisus terrestris. Here, the forms of male and female genitals and sexual acts are shown as echoes of the riotous growths and extravagant charms of similar-looking botanical specimens. Hall’s tableaux are frequently sober, even dark, fantasies and furies with apocalyptic overtones. In her ‘Words’ and ‘Divine Comedy’ series, figures cut in thin metal relief twist and contort. In the beginning according to Genesis, the Word of God was generative and all encompassing: image and text were one. After the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, knowledge of good and evil became the perils of choice and conflict, and words became a scourge as well as a source of enlightenment.  | | #10 Fiona Hall, Words, 1989 | Hall’s imagery reworks religious, cosmological and scientific imagery drawn from medieval and Renaissance texts as well as the literary images of such twentieth-century poets as T.S. Eliot. Her current work is in object- based installations of a more conceptual nature. Hall is no born-again Christian Fundamentalist obsessed with sin and divine retribution.10 Her appropriations from past art and literature serve very contemporary concerns with ecological perils, social intellectual confusion and imbalance, as well as her fascination with systems of knowledge. Her perspective is informed by a childhood spent with parents deeply committed to bushwalking and conservation issues. Hall’s recurrent subjects referring to scientific systems also relate to her mother’s profession as a physicist. In the light of Hall’s speculations on the relation between culture and nature, the floral motifs of carpet and chair become intimations of the fate of human cultures after the Fall, outside the Garden wall. Human pattern-making would imitate and aspire to harmony with nature but remains, undeniably, interior decoration. To point out some continuities from early to later styles is not a game of identifying old wine poured into new bottles. The artists I have discussed have in common certain strategies and forms of evolution. Similar movements can also be seen in the work of Christine Cornish, Ingeborg Tyssen and Debra Phillips. They transgress medium boundaries or step into realms once denied photography (and women). They address aspects of western culture and history and in doing so they have also taken on the ‘Big Picture’ genres once the preserve of the ‘fine arts’. Sue Ford, for example, makes new ‘History’ pictures. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the grand history picture treating an historical theme with contemporary reference was the peacock’s tail whereby aspiring painters made their name. Allan and Hall make their works within some of the oldest and deepest of spiritual and intellectual themes and traditions of western and eastern cultures. Political dimensions are present in differing degrees, but in all their work there is also a politics of women being free to roam where they please.

Footnotes - The Photoforum was held in association with the launch of Joan Kerr’s book Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book, Art and Australia/Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995. Quotations are from the author’s notes.

- Typescript essay, ‘Women at Watters: 1964-1994’, Watters Gallery, Sydney, February-March 1995. A nationwide program of women’s art exhibitions was instigated by Joan Kerr in association with Heritage as part of the twentieth anniversary of International Women’s Year.

- See Gael Newton, On the Edge: Australian Photographers of the Seventies, San Diego Museum of Art, California, 1995.

- See Micky Allan, Perspective, 1975-1987, Monash University Art Gallery, Melbourne, 1987. Catalogue essay by Memory Holloway.

- On the invisibility of women photographers in the 1960s and early 1970s see my article ‘Gender, journeys and genres’, Eyeline, No. 24,1994, pp. 18-22.

- See Helen Ennis, Australian Photography: The 1980s, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1988; and for feminist uncertainties about the relation between younger women photographers’ practice and feminism see my article ‘See the woman with the red dress on’, Art and Asia Pacific, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1994, pp. 96-103.

- Considerable shifts in subject and style appear less in the work of male photographers of the period. Women are seen as having embraced post-modernism and to dominate contemporary photography; for discussion of this perception see ‘Gender, journeys and genres’, op. cit.

- The ‘Van Diemen’s Land’ work needs to be seen in context with the contemporary political references of ‘The Kakadu Suite’ which was exhibited with it; see Helen Ennis’s catalogue essay for From Van Diemen’s Land to Video Land, Canberra School of Art, Canberra, April-May, 1993.

- See curator Kate Davidson’s essay for Hall’s retrospective Garden of Earthly Delights: The Work of Fiona Hall, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1993.

- Hall’s interest in relations between macrocosm and microcosm and her cited sources (such as the radical scientist-theosophist Rupert Sheldrake) do, however, have a context within a Renaissance gnostic and hermetic tradition which sought union between secular and religious systems of learning, a ‘natural religion ... behind [which] diverse philosophies and religions there was a unity’; Paul Johnson, A Histoiy of Christianity, Penguin, 1976, p. 268.

Ilustrations Most images are as published originally - a couple have been repalced due to availability. #1 Sue Ford, Sue 1996, from the My Faces Series 1975, Collection NGA #2 Micky Allan, The Family room (Self Portrait) 1982 One of 12 photographs with oil paint, Collection NGA #3 Micky Allan, Babies 1976, Three from a series of photographs with oil paint, Collection NGA #4 Micky Allan, Botany Bay Today, 1980 3 from series (not included in the orginal) Micky Allan, An Abstract Place, 1984, oil and oil pastel on Canvas, Collection NGA (originally included - not illustrated here) #5 Micky Allan, Garden of the rolling horse I, watercolour, acrylic and pencil on drafting film and paper, Collection NGA

(Garden of the rolling horse II was in the original article) #6 Micky Allan, Untitled, 1984, oil and oil pastel on Canvas, Collection NGA (not originally included) #7 Sue Ford, Lynne, 1964 and 1974, Collection NGA #8 Sue Ford, Haunted 1992, Collection NGA #9 Fiona Hall, Words, 1989, from the ‘Words’ series, Polaroid photograph, collection NGA #10 Fiona Hall, Leura, New South Wales, 1974, Collection NGA

Links Web site for Micky Allan Web site for Sue Ford Web site for Sandy Edwards - Arthere Web site for Helen Grace Web site for Eugenia Raskopoulos Wikipedia entry for Fiona Hall

Extra Links Re-constructed Vision, Contemporary work with photography 25th July-23rd August, 1981 Australian Women Photographers: 1890-1950 Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Australian Feminist Photography reviewed by Gael Newton gender, journeys and genres, Eyeline Magazine 1994

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles |