1983/1984

Interview between the Australian Centre of Photography and Gael Newton

Original 1983 Introduction: Gael Newton is Curator of Photography at the Art Gallery of NSW. She is the author of 'Silver and Grey — Fifty Years of Australian Photography 1900-1950", "Max Dupain" & "Axel Poignant". She also edited "Philip Geeves presents Cazneauxs Sydney 1904-1934". Her published essays include "Australian Pictorial Photography" (exhibition catalogue published by The Trustees of the AGNSW), "John Kauffmann 1864-1942 Art Photographer" (in "the Australasian Antique Collector "no. 20, 1980) and "Reconstructed Vision"(AGNSW "Project 38" catalogue). To explore historical and contemporary issues raised by her engagement with the medium, an extended interview was conducted by Mark Hinderaker and Mark Johnson at the ACP on 14.5.83 and at the AGNSW on 12.10.83.

for more on Gael Newton AM - click here

The Interview

this is a very long read (12,000 words) - originally it was spread over two issues of the ACP Magazine in 1983 and 1984

ACP: Gael, could you describe how your interest in visual media developed?

Gael: My father was an amateur painter and my mother was an amateur historian and novelist, so it wasn't surprising that I took art and history at school.

The difference between my interest and theirs was that I became fascinated with style history ... why people painted like they did at a certain time, period studies. I've always been more interested in how we are constructed by the influences on us.

My work in art history, looking at relationships between style and culture, has a very direct and personal end, in that I hope one day I will understand what influences operate on me. It's a matter of determining what position you're going to have on something, knowing where your ideas are coming from. |

|

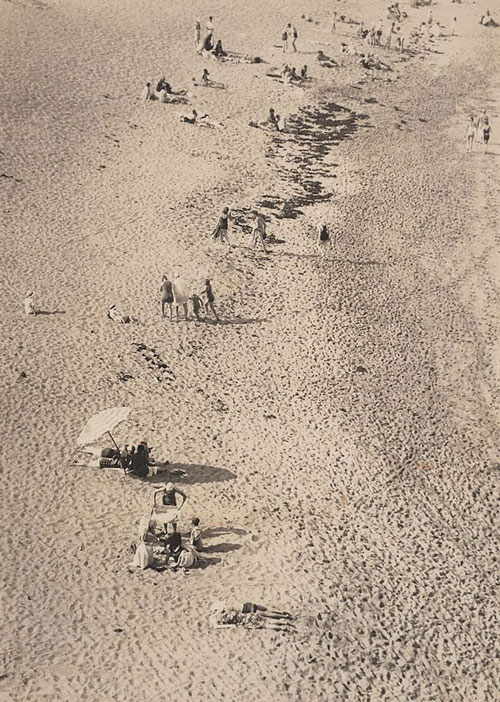

| Beach Scene, Bondi 1929-1930 Harold Cazneaux, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: In terms of individual people and bodies of work, what have been the influences on the development of your ideas about photography?

Gael: My involvement with art history so predates my involvement with photographic history as a part of it, that it's really what influenced me in art history.

The basic influences, apart from the early obsession with style as a psychological picture of a people, would be Sydney University courses and teachers.

I was very influenced by Professor Frederick May. He studied every line in literature as an image which gave away other meanings. We ended up probably over-analyzing the most casual, nonchalant gestures!

The other major influence was the newly opened Power Department of Fine Arts. The approaches to art history they taught obviously affected me. Terry Smith in particular was a major influence on method. He'd probably be rather distressed to hear that today! He taught us to approach a work first by describing it physically, in almost banal terms – "this is a large painting; it is made of thick paint"!

It made you look, and also gave you confidence because often you'd go away and do the biographical research and discover that you already knew all that about the painting anyway, because the information was there. I think he would probably rather that I had developed more of a social and political conscience about what I was looking at, than be indebted to him for a more generalised method!

Professor Smith, with whom I worked for a while later on, taught me a lot about how you do research. His book, 'European Vision and the South Pacific, was discussed in a radio program dealing with books that had substantially changed the way people thought. That attitude of looking at Australia as something precast in British eyes, has had a profound effect on my work, as an Australian trying to find out how we are constructed by all the ideas that existed about Australia before anyone even came here. I don't feel I've really 'tied in' or expressed that work yet, because I think it would have to do with historical nineteenth century photography as well.

|

| Old time Merry-Go-Round, 1911 Harold Cazneaux Bromoil print c.1930s, AGNSW Collection |

I went from Sydney University to Elam Art School, at Auckland University, to do a Bachelor of Fine Arts course, which wasn't then available in Australia. I was there from 1970 to 1972. One of the reasons for my leaving Sydney University in Second Year to do that was that I had been doing a lot of art work of my own. I was a painter, potter, jeweller at times, and I felt that I should really go to art school and see if I did have enough talent to become an artist. I had a wonderful time there, it's one of the great experiences of my life. It was a small art school and had a very binding, homey atmosphere. We had a lot of parties and dressed up a lot. Most of the gear that people wear today ... I can remember wearing slitty little black glasses and having punk haircuts in Auckland, and shaving my eyebrows and doing all sorts of things! Being more conservative, I think because of my academic background, than a lot of the other students there, it was less spontaneous for me, but I enjoyed it very much.

I did photography in First Year there, as part of the core course. I had a great feeling for photography, but I'd never thought about it before. I wasn't a natural photographer. I don't even take snapshots, then or now. I liked the humanism of photography. So much art was abstract. I was interested in the real significance of abstract imagery, but I had so much more to work on with images of the real world, and it so related to what I had already done.

I liked Tom Hutchins tremendously. He was a very principled man, to his cost. I liked the way he always talked about the subject of a photograph. As he did, eventually you'd see that he'd made a very indirect but accurate criticism of your work. You'd suddenly realise that you'd nearly had the photograph and had missed it for this or that reason. I found that a very constructive approach. Some of the other teachers tended to come straight in and dismiss the photograph for formal reasons. That didn't help me very much at all.

I took photography as a major, and completed my art history under Professor Green. But after about the second year I began to feel that the other students really were artists and that I wasn't, and that my real passion in life was art history. I passed the rest of my time at Elam I think under the kindness of John Turner and Tom Hutchins. On returning from Auckland, I got a temporary job at the Art Gallery of N.S.W. as an Education Officer. It was then that I learnt about curators. As soon as I saw what a curator did, I decided that was perfect for me because I had both an academic background and an interest in dealing physically with the objects.

With both an art history and an art school degree, I felt I would understand the objects better, and the artists better. I could also see that it was inevitable that photography would be accepted at the Art Gallery because Daniel Thomas had already put into operation negotiations to accept a gift of Harold Cazneaux' photographs into the Department of Australian Art. Because I was on staff, even in another capacity, I was given jobs to do in photography. I did a lot of work with the Cazneaux photographs.

When the 'Cartier-Bresson's France 'exhibition arrived, I was left there at five o'clock to hang my first exhibition, which was, like every other aspect of my job as a curator at the Art Gallery, a case of being thrown in at the deep end, rather than being able to be apprenticed to somebody and seeing how it was done.

I became more and more responsible for the photography, and by 1976 I was asked to put together a policy for a formal Photography Department, though it wasn't until quite recently that I was made Curator.

ACP: Could you outline the policy you proposed for the Department?

Gael: Copies of the policy are available from the Gallery if people want one. Basically, I proposed a number of options for the way in which the Gallery could deal with photography. One of these was for them to make a large foundation grant, so that I could buy examples of the history of the medium, because at that time you could still buy an Edward Weston original for several hundred dollars. But they rejected that outright, which was unfortunate.

I also suggested ways in which we could concentrate on certain themes, because even right from the outset, there was a problem that the level of funding would be unlikely to be such that you could do anything properly. You couldn't even collect Australian photography properly, certainly not in comparison with the way the Philip Morris Collection was being put together. I always felt that we had to narrow our focus, so that at least we did something well.

The option that they accepted most readily was for us to begin to mount a survey of Australian art photography from the turn of the century down to the beginning of the contemporary period, the beginning of the work collected by Philip Morris, because that made use of my academic background, because such a survey didn't exist and because we already had the Cazneaux gift. So it seemed most sensible to look at Cazneaux and his contemporaries first, then the next generation, and build on it that way.

We would in fact not have time to research nineteenth century photography and I didn't feel I had expertise in that area. I was also concerned that collections such as Philip Morris and the few galleries that were starting to collect and promote photography were putting forward the idea that you bought a lot of photographs from one photographer which might represent only one or two year’s work. This reflected the notion that you couldn't represent a photographer by several single images, that you needed a substantial body of work to represent them, or it wasn't worth doing at all.

In the first years of collecting, this did cause some heartache, for curator and photographer, whereby they had an expectation that you might buy ten photographs from a recent show, in order to represent them, which would of course leave you with the problem of perhaps buying ten more next year, and ten more the year after, which would reach ridiculous proportions. I was concerned about this notion that the single image didn't suffice, and that what I was doing wasn't worthwhile if I couldn't buy more. My historical background made me suspicious of that process. I looked back at Cartier-Bresson and other major photographers, and looked at the length of their careers, and how many pictures tended to be included in monographs and exhibitions. It came out that they'd produced about five a year. I thought that if Cartier-Bresson doesn't produce more than nine significant images that the future is interested in, then the chance of my local photographers producing more is rather slim.

I wanted to back off, to let time pass before I started spending my money on them in a heavy degree. It's only recently that I feel we've completed those historical surveys, so that now my future is to think of a contemporary policy.

ACP: You said that your mandate was to survey art photography from the period in question. What criteria did you use to distinguish art photography from other photography?

Gael: We stressed that we were going to be involved with art photography because we obviously had an option to collect the history of the medium, even down to equipment, snapshots, historical photographs. We decided against that when the policy was put together because it was thought enough to get the Trustees to accept the photography that most looked like contemporary art, and that most resembled and shared concerns with the contemporary art scene – visual arts as we knew them.

|

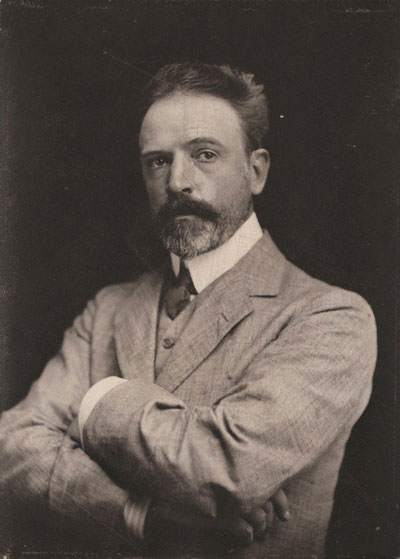

Portrait of Arthur Streeton, circa 1905, Melbourne, Alice Mills,

Platinotype, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: Did art photography present itself as sharing perceived contemporary concerns?

Gael: Yes. We felt that it was most logical for us to look at the photography that seemed most closely associated with an art museum. Remember that the AGNSW is quite a narrowly focussed art gallery. We do not have large collections of the decorative arts. We have only a small collection even of tribal art or Asian art. I deliberately excluded historical photographs for their own sake, and equipment, and concentrated on what art photography in this country looked like in order to make conclusions about how it functioned as an art.

ACP: How did art photography present itself as such? How did it present its affinity to the concerns of an art museum?

Gael: As I said before, for practical reasons we decided to build on our Cazneaux collection, and to look at his contemporaries, so in fact we were looking at the most visible art photographers – visible by their publication in photographic magazines, by their exhibiting activities. This process involved primary research into re-finding those people, finding what work remained in their families and constructing a collection to represent that very visible type of art photography in those years, from 1900 through to 1960 – which of course is not just the Pictorialists, but all of Max Dupain and his generation, and Axel Poignant and David Moore.

Primary research of that kind involves many fruitless hours of telephone calls, library visits, cups of tea with elderly daughters and sons of the photographer, which you can't rush. The danger which we were always aware of was that, by choosing the logical and certainly convenient starting point – visible art photographers, whatever we did, being the Art Gallery of NSW, would then be interpreted as an exclusive definition of art photography. Perhaps we've even reinforced that by the convenience of certain titles, like "Silver and Grey – Fifty Years of Australian Photography 1900-1950, some of which are simply mechanisms for avoiding endlessly qualified titles.

|

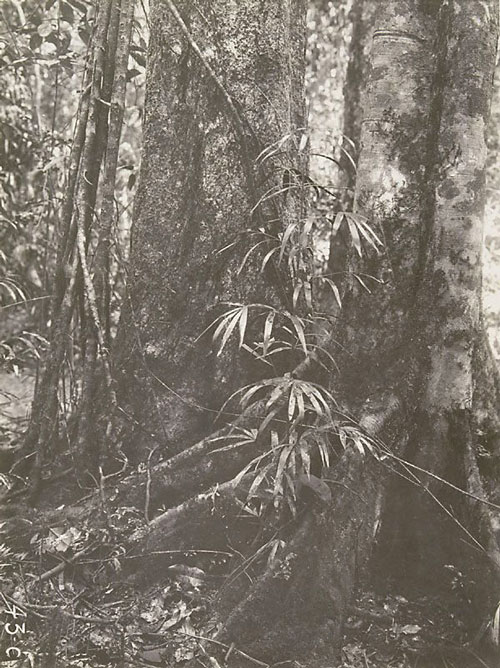

| On Sussex Downs 1899 F. H. Evans, AGNSW Collection |

We have tried to qualify when presenting the work of the Department, by stating that that was our project, and that it was only a project, and that we certainly hope it will provide something for other people to bounce off and begin many more deeply layered examinations of the same period, going from people whose work might then be appropriated into art photography but who never ever saw themselves in that context in their lifetimes, to what I call vernacular photography – the genre photographers' work.

Another problem associated with that tactical decision to begin with the convenient node of photographers who were visible in their own time, and to present their work to the Board of Trustees, who had then the final say on acquisition, was that if you present to them work with obvious affinities with other visual arts of the time, you run the risk of not stretching their concept of photography and presenting publicly a very narrow stream of photography as art. Whereas most people involved in photography want to see the definition of art expanded to accommodate that photography which has seemingly very little relationship with formal art movements.

That is my biggest regret, particularly when I saw Jennie Boddington's portrait show and saw that in her collection she had cricket photographs and small daguerreotypes and a wonderful physical range of material. I wondered whether I had been too fainthearted in approaching the Board. When I thought back, I remembered the bitterness that accompanied even trying to have the Board accept a quite conventional photographic essay. It really was just difficult enough to get the most conventional kind of art photography, past or present, accepted by the Board of Trustees. They had enormous problems with the notion of the extended body of work. We lost, in fact, a very major virtual gift because they just weren't going to let someone be represented by thirty-six photographs.

I noticed that Jennie Boddington referred in her interview to some similar problems in the early years with her Board about the area of vernacular photography. I think there wasn't anything else I really could have done in those years. The situation is different now. Most public art galleries like this gallery have a Board of Trustees system which has the final say on approving works of art recommended by the curators. As far as I know, no curators have the ability to purchase and acquire work directly without that system of approval.

At present, the majority of my acquisitions only have to be approved by the Director. This is a reflection of the smallness of the budget. It doesn't represent a major decision about the allocation of funds. Because of past anguishes over conflicts between my views and the institution's views, it was felt that it was best to leave it to the professional staff and the Director.

ACP: From your own research experience, do you have any suggestions as to how work from the past which was not done in an ostentatiously artistic way may be discovered and adequately researched?

Gael: My research methods are geared to more visible people. I think you enter into the areas of social and historical research. It would be better, probably, to look to historians in that field and their methodology. However, it's a much more complicated and time-consuming process because you're not even sure what you're looking for. At least I had a list of people that I needed to find again – where their work had gone, where their families had gone, to check birthdates in electoral roles, addresses in old telephone directories, and read through all the Australasian Photo-Review magazines. Fairly simple stuff, really – very enjoyable.

There are a lot of people working on the 'other' photography, if you like, the less visible. There are also lots of people working on the areas outside of art photography which are valued for social and aesthetic reasons – the nineteenth century portrait photographers, the type of photography where you're not so concerned with the profile of the 'artist' or the author of the photograph, but where you're looking at studio practice or commercial practice.

Because that's a much more time-consuming process, there hasn't been a great deal of publication of that research. It's all to come. For example, the Macleay Museum and Allan Davies – the index which they're going to publish, I think next year, of all studio photographers down to 1900. That will make research much easier in those areas. I have some doubts about the theory that is put forward sometimes that the 'real' art photography happened outside of all of the people that I deal with and that our collection is not the true art photography of the period, because I never 'felt' its existence when I was researching.

You get a feeling for what's being done in a period. I would be surprised if, in Australia, we had an unknown photographer come forward whose work is brilliant. What we'll find, as we are finding, particularly in the turn of the century era, many extremely interesting collections of glass negatives, perhaps prints, with great charm and social value. I'm not sure that the picture of art photography as such will be totally reversed from the way we've presented it, the people who were quite obviously trying to push photography into expressive ends. However, one hopes to be corrected on that!

|

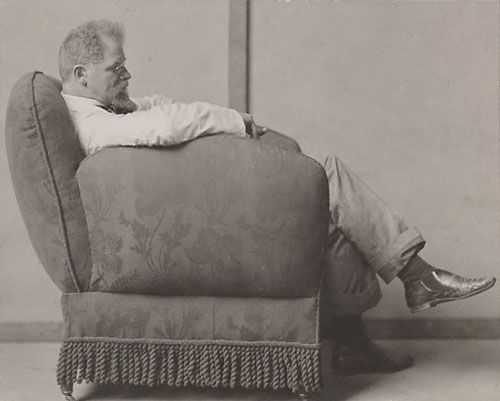

| Portrait of Max Klinger, circa 1910, Anon European, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: Regarding your policy for the exhibition of historical material, apart from what you consider to be the artistic importance of that material, are there other reasons you might have for exhibiting work?

Gael: Yes. Of the work of the photographers from 1900 to 1960 that we have in our collection, I haven't been able to exhibit all of it, because much of it I find just isn't up to exhibition standard. It's interesting to have in the drawers in relation to that photographer, but the works are just not strong enough for exhibition. I do sometimes include works because of their significance, perhaps, in the photographer's career; they may not be fully resolved works, but key works, leading to other pictures. Especially if we're dealing with a photographer or a thematic survey of a period, you need to include indications of the process whereby the more resolved images were arrived at.

Although I have found in practice that work that isn't exhibitable doesn't tend to be used very much, and that really a copy photograph or a slide probably would have been just as good in the archives rather than having drawers full of work that you know won't ever come out on view. But often I didn't have the choice of taking three photographs from a collection that's perhaps dumped on me, in some ways. If I wanted the three, I had to take the other thirty. I personally couldn't take the responsibility for throwing them on the fire, as the case was in one situation where I either took them then, or... the lady was standing by the fire, and that was it!

I then felt as a curator, I couldn't be responsible for disposing of that material, although I have broken some collections up, and sent them to what I thought were other, more appropriate homes, where perhaps the interest was in the social subject matter, rather than the quality of the print. Or, I used to be terribly democratic and try and send work from each photographer to a few more places, rather than have the only collection of work by that photographer. You can't do that now.

ACP: The Pictorialist era has been a particular interest of yours. You once wrote that the Pictorialists wished to establish photography as an expressive art which shared the concerns of contemporary artists of their day. Some writers have noted a striking contrast between pictorial photography and art of that time, indicating that, at least in Britain, Pictorialists were largely ignorant of developments in art of their time. Do you feel that Pictorialists shared any of the concerns of artists of the early twentieth century?

Gael: John Kauffmann was reputed to have introduced Pictorialism to Australia in 1897, when he returned from Europe. However, the situation was much more complex. By the time he returned, the whole of the Adelaide art world was already engaged in a debate about the merits of an impressionist style over a highly detailed realistic style and I think I proved that quite reasonably in my article on Kauffmann. That made me realise, with a jolt at the time, that I hadn't, in fact, applied my art history method to photography very well, that I had accepted the mythology of photographic history that I had learned at art school, and not questioned it enough.

Particularly for things like Pictorialism, I see them as being totally embedded within the aesthetics of the period. You certainly couldn't say that Pictorialism was as radical an aesthetic as was being developed in some European centres, particularly after the turn of the century, when there was the development of abstraction in art. So Pictorialism was part of a more popular aesthetic of the day, allied to the turn of the century's interest in tonal impressionism of the school of Whistler.

Stieglitz's movement towards abstraction represented a much more radical position vis a vis the rest of the art world of his time, just as the painting he was exhibiting was far more distanced from society than painting in general, in conventional art circles.

And there are all sorts of different viewpoints on the period – Humphrey McQueen, in 'Black Swan of Trespass', very wittily criticizes the art historical obsession with the avant garde notion of art movements. He saw it as a train, with a guard on the platform and a lot of people with suitcases – you check off all the people getting on the train, you check who's got the biggest suitcase and that's how you determine who's good in a particular period.

|

| Design for a frieze, circa 1920s, John Kauffmann carbon print, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: Yes, but the Pictorialists demanded to be seen in artistic terms rather than in purely photographic terms. Therefore, one is obliged to assess the work qualitatively, in terms of its achievements vis a vis other media at the time.

Gael: Yes, but the thing is that we might compare Pictorialism with the development of abstract painting, but in fact Pictorialism was well matched in its interests and topicality at the time by, particularly, graphic arts. You could ask whether etchings by Syd Long are comparable to proto-abstract works by Kandinsky. I wasn't the case that they were so much behind the times. The whole of the art scene was much more conservative and it filled different functions. There were plenty of other painters and graphic artists doing similar kinds of work – and it was seen as a new taste then, this taste for an impressionist effect, a poetic impressionism. For example, in Adelaide there was great controversy over Syd Long's 'The Valley', which was very tentatively art nouveau style. You've got to remember that was the context in which they saw themselves as being new and different, not our hindsight on the development of a more abstract art.

ACP: What has been the effect of researching the Pictorialist era on your thinking about the medium?

Gael: I was doing research on what was regarded as a joke, a cul-de-sac in the history of photography. Certainly, Gern-sheim and the first historians of the medium, who wrote from a strong commitment to a realist aesthetic, tended to put out a picture of Pictorialism as something that, in Stieglitz's words, when he repudiated early Pictorialism, confused "art likeness with art" in photography. We still largely operate from the notion that photography's inherently a realistic medium, and there's a moral obligation as well to remain within that definition of photography.

Pictorialism seemed, in its anti-realism, to be a mistake. I started out with the same view; I found it very difficult because I was a seventies street photographer by training. If I wasn't trying to make street photography myself, I was interested in other street photographers, or I was interested in the 'thing in itself school of Edward Weston. I found it very hard; the retouching on the prints, for a start, was always a shock. But since I've studied the history, I now don't have anything like that confidence that contemporary photography is so essentially different in the way it operates, from the way the Pictorialists operated.

|

| Lawyer Cane 1890-1910 Anon, AGNSW Collection |

In fact, I see a lot of parallels between the Pictorial era – which was very art conscious, with a predominantly salon-like approach to photography and an art-for-arts-sake aesthetic – and our contemporary era, as opposed to the latter forties, postwar era, which was dominated by photojournalism and documentary photography, and a concern for realism, humanism and social concerns. We now seem to be in a very aesthetic phase. Some of that sense of moral purpose of documentary work seems to be faltering – I think that's a shame.

People confuse my commitment to doing a survey of Australian art photography with a necessarily strong commitment to that over any other kind of photography. But I now think that the contemporary photographic scene isn't as different as I would have expected. Pictorialism is a perfectly valid part of photographic practice. I don't have problems looking at it within the history of photography. I don't want to frog-leap it, from interesting documentary photographs of the 1860's, and then pick up in the 1940's and go on from there. I see it as something which laid down many of the attitudes to art photography which we have, much of vocabulary almost, by attempting to do things in a more aesthetic fashion, to make photography more expressive of things that nineteenth century pioneers didn't consider.

They are our forebears much more than people are prepared to admit. I don't see it as being something that one regrets the persistence of in Australia; it just was, it was part of time; it was, like a lot of other arts of the time, interested in certain types of poetic idealisations. The influence of the British 'Photograms of the Year' on Australian photographers was, in my view, no more than what the influences of Creative Camera' and Popular Photography* will appear to have been on what might, in fifty years time, seem to have been the persistence of certain types of 1970's aesthetics in photography.

I suppose that's where I'm different, I don't have any commitment now to the moral superiority of contemporary photography over Pictorialism.

|

| Sun Portrait (Lesley Snugden) 1931 Harold Cazneaux, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: You mentioned Photograms of the Year. What were the other influences from Europe, Britain and America which operated upon photographers in that time, and subsequently in Australia — say in the first 30 years of the century?

Gael: Photograms of the Year' and a couple of other, basically British magazines, were the main contact that Australian photographers had with what was happening within Pictorialism overseas. The American and European magazines don't seem to have come through with nearly the same consistency for obvious reasons, particularly with foreign language difficulties. With American magazines, I think that the market wasn't interested in such low volume. There were a couple of American magazines that did come through – the Amateur Cinematographer, the American Annual of Photography', for example – but Australia, of course, saw itself as much more of a British society in those days, so their main allegiance was to Britain, and they knew more about that than anything else.

Falling into the trap, myself, of seeing things in terms of histories of avant gardes, it was obviously important in Australia that Australians had no idea of what happened once Stieglitz left the British circle. When he split to form the American arm of the Photo-Secession, there was a little information that trickled through but basically, people out here had no idea of the new position that he was developing, nor did they, in the early days, have much idea of the more adventurous work that the American Photo-Secession produced, as opposed to the run of British salon work, because Camera Work, for example, was unknown in Australia.

It certainly seems that no one subscribed from Australia. I can't find any holdings in libraries of Camera Work' contemporaneous with its publication. Harold Cazneaux had one copy from 1909, and again, it was pre the change, with Stieglitz still producing work that was very accessible to Pictorialists. If Cazneaux had seen where Stieglitz went and where the American Photo-Secession developed, that being the very flexible person that he was, and talented, he probably would have only needed to see a few and he would have also made a similar sort of change, but Australians didn't know what had happened. That applied later to another generation around Weston – they had very little idea about what was being done by Edward Weston until quite late.

I was surprised while researching Max Dupain, how late his acquaintance with major figures like Weston was. He said he never saw the work until it started coming through in the American annuals, which was after 1949. You do see a few Weston pictorial works in 'Photograms of the Year'.

The main influences on the Pictorialists were British, but again I want to stress that it's not a case of simple derivations. The society that was producing Pictorialism in England was not so radically different from the people here. They were all moving together in the same format. Certainly, we can't claim that Australians were pioneers of it, but it's not a simple case of derivation. They were participating in a worldwide, western cultural aspect of aesthetics at the turn of the century, and perhaps we have fewer people and they're not always as many, or as adventurous as their models, but it’s not quite so simple as aesthetic copies.

|

| Fifteen-year old punching cards, Boston Index Card Company, circa 1910, Lewis Hine, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: It's very much the aesthetic context of the salon and the international publications.

Gael: Obviously, publications were vital to the spread of Pictorialism and art movements generally, and that has actually a whole history in itself. Perhaps the reason why Pictorialism, as opposed to other art movements, was so early and so quickly spread right across similar communities – even in places like India, there were pictorial clubs, very similar in the 1920's – was that you had mass circulation magazines to spread it. And I think that they didn't have to see everything to be able to get the general idea, because their own society was involved with similar developments.

Max Dupain's era, of course, was very heavily involved with German magazines, like Das Deutsche Lichtbild. Again, I was really surprised that the old view of Australian culture being so derivative wasn't true either. Again, it was a situation of a social complex of Western people at that time being interested in certain things, so Max didn't have to see 50 magazines. He saw a few and got the idea pretty quickly and, I think, fairly well. But that's assuming that you think you have to see and experience the new developments at their centre, or you won't understand them. That's not seeing that we are part of the same continuum.

|

| The surf wheel circa 1930 Harold Cazneaux, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: That's also assuming there was a centre. Perhaps a lot of these things didn't really have a centre. Maybe they had a publication or an exhibition that was a centre, but there may not have been an active group that exchanged ideas, except in the pages of journals, or through pictures.

Gael: One of the things that I seem to end up shying away from, because I am trying to present a view of Pictorialism as integrated within the history of art of that period – and also integrated within the history of photography – instead of some sort of blind alley that it's often depicted as, is sounding as if I'm saying that it's totally equivalent to all other photography. Certainly, looking back over Jennie Boddington's interview in the first issue of Photofile, I think she makes an excellent case that the humanism of documentary photography, and that philosophy, is a very sympathetic one, and one whose absence, the more you are committed to a humanist base, you will find distressing in Pictorialism.

It is extreme formalism, compared to photography which has nourished itself by referring to the human condition. Yes, ultimately, perhaps I would support those distinctions too. I can become very academically interested in Pictorialism for what it signified, and I don't believe that there's such a difference between Pictorialism and contemporary photography in lots of ways. But in the end, too, I suppose I always do feel a certain regret that, with any form of excessive formalism, it doesn't touch base with the way people live their lives. Certainly now, with the new critiques of the arts from semiological points of view, from structuralist points of view, and from Marxist art theory, it has a curious, emotionally cold dimension to it, in its obsession with form, but that can apply to any art of that type, any excessive stylisation.

It's important to see it more consistently as part of the history of photography and to enjoy the work which was good. I suppose it has affected my thinking about contemporary photography, and gives me a great deal of distance from it that I once didn't have as a practitioner of the aesthetic of contemporary photography. I now have a distance, I think, on my own aesthetic. I'm not free of it, but I can perceive it in operation by bouncing off something that seemed to be so different and discovering that it wasn't as different as it seemed.

|

Sarah Bernhardt 1880 New York, Napoleon Sarony, Cabinet Card,

AGNSW Collection |

ACP: Do you think the propagation of Pictorialism via the publications you mentioned to any extent suppressed the development of whatever indigenous identity was here to be developed?

Gael: That's a difficult question because it applies to any area of culture in Australia. It's the old cultural debate: would we have had a great national school and therefore have fed back into the history of Western culture by being innovators that influenced the whole of culture. That debate rages continually in Australia and I don't know if I've got any simple answers to it either. It's a hypothetical question – we don't know because it didn't happen.

It was very difficult to develop a strong, national culture post 1900, because the international community is just that – there are tremendous means for ideas and influences to spread quickly, so it's much harder, since the development of the media, for cultures to develop separately in any really strong, totally unique fashion. I don't know whether, if Australians hadn't been able to find out anything about Pictorialism, they would have developed a unique school of Australian photography.

ACP: In painting, one can retrospectively construct a national development of style. If one looks at Tucker's work, it was quite out of step with the avant garde in Europe, but it does make a lot of sense in terms of the evolution of the medium in Australia.

Gael: Yes. When we look at the history of Australian photography, it does seem very embedded in general art development, until the generation of people like Dobell, Tucker, Boyd. There doesn't seem to be a photography that parallels their work. Max Dupain, for example, illustrates a lot of themes up until those people, but I feel they then part company in some ways. We look affectionately at those artists as having made some sort of extra Australian contribution. I don't know that the photography was the same, or as strong – it certainly hasn't seemed to me, in doing the work on Silver and Grey' which goes through that period, that one could argue for the existence of a photographic parallel, but I'm not a hundred percent sure.

ACP: With reference to the present as well as the past, have you noticed characteristic regional modes of photographic practice in Australia?

Gael: I think so. It seems to me that Sydney, at least, has produced photographers who are rather gutsy action shooters – I can't think of anything less colloquial than that to describe it! Perhaps that is something to do with the notion of Sydney as a rather brash and energetic centre – you look at the photographers and their values seem to be in terms of power and energy rather than the contemplative, fine print tradition that we perhaps know from looking at world photography.

That really surprised me, doing 'Silver and Grey', I kept thinking I was going to turn up a Weston or some school like that, and I never found it! Maybe it's there, but I didn't find it. Whether that was because we didn't see much of that kind of work then. I think that it has something to do with Sydney. That there's no fine print tradition in Sydney isn't a coincidence, I think it has something to do with the cultural milieu here. It's one of the reasons why landscape photography isn't as strong in Sydney as it seems to be in Melbourne, consistently over the years.

|

| Legs in sand 1928, Herbert Bayer, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: What aspects of the cultural milieu did you have in mind?

Gael: The old notions of Sydney being brash and Melbourne being reflective may well be true – they certainly seem to have a stronger landscape tradition. When putting "Silver and Grey' together, there was landscape work from Sydney, but I didn't find it very interesting. It seemed weak in comparison to the portraits and urban shots. That's the most interesting thing: why did Sydney photographers abandon large format work as soon as they could? Why has there been no major figure using large format, using realism in that way?

I suspect it may have something to do with the milieu of Sydney. It's a curious thing, that with landscape becoming so important in Australian painting, that it doesn't seem to occupy the same central position in photography – and that's the one thing I thought I would find when I started working, that there'd be a close parallel to the dominance of the landscape as an arena on which to project your ideas that there is in Australian art in general. It doesn't seem to exist in photography.

ACP: Perhaps it exists, but was done in an artistically unselfconscious way, and is tucked away somewhere in a loft, or a garden shed.

Gael: Yes. are there important bodies of work that haven't been discovered that would greatly change the interpretation of photography? I hope there are – I don't actually suspect it. but I hope there are. because it seems a curious lack, in landscape.

ACP: Are there any other areas of characteristic regional practice that you'd like to talk about?

Gael: I haven't perceived any, historically. But obviously, my research outside Sydney is weaker. I think there are regional differences in contemporary work, and also in the climate of the work. For example, I find that in Melbourne. I invariably am involved in more discussions about photographic issues than I am in Sydney. I always find that the Melbourne community tends to have a more theoretical approach, whereas in Sydney, perhaps, there's an almost anti-intellectualisation of photography.

ACP: Do you think it has something to do with the weather?

Gael: Probably! Probably, the Sydney people are all out there taking photographs!

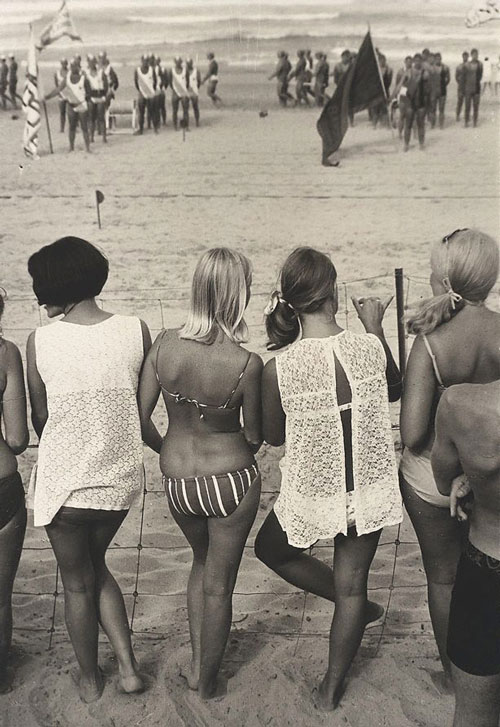

|

| Surf Carnival Cronulla 1960s, Hal Missingham, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: What do you think is the value of present-day photographers of some sympathy towards, or knowledge of the history of the medium as it’s been practiced in Australia, as opposed to the orthodox histories we import from overseas?

Gael: I suppose it depends on whether you accept the existence of traditions which form art practice. If you do accept that model, then to find what the traditions were in Australia, even to identify areas of neglect – as in my view on what happened in landscape in Sydney –becomes an important means of identifying concerns within contemporary photography, and understanding them better. I can't give an unbiased opinion because so much of my life has been devoted to the notion that a historical perspective is, a priori, helpful.

Certainly in my own view, all my knowledge has come through having a historical perspective, through having seen how something you are detached from operates, and then applying that knowledge to give you a perspective on what might be influencing you now, so that even though you participate in it, you have a glimpse of where you begin and where the influences on you begin and end. I suppose I feel that perhaps that would give you a power over your life and a power over your work. But that's a very academic approach.

ACP: Do you think that historical perspective should include more than an awareness of traditions – perhaps equally, just an interest in work from the past in our own region, on its own terms?

Gael: Yes, it's also a case of enrichment. To be obsessively interested only in what is contemporary is to deny yourself all the richness of experience outside the contemporary sphere, of different kinds of experience. Who would want not to have the experience of looking at daguerreotypes. It's the diversity that is offered by looking at cultural experience outside the immediately local and the immediately contemporary that's valuable. There has been an enrichment from identifying, from time to time, with certain areas of past practice, and using this as a springboard to develop away from the status quo.

-1934.jpg) |

| Untitled (Schunk department store, Maastricht, The Netherlands) 1934, Werner Mantz, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: Particularly overseas, a lot of nineteenth century work which was not done with primarily artistic motivation has been recently re-evaluated so that one now appreciates subtle formal qualities operating in the work of, for instance, O'SuIlivan in America. Do you think a similar process or re-evaluation will occur with earlier work from Australia which perhaps formally has not been seen to possess much interest?

Gael: Within the next five years at least, the whole concept of looking at the visual arts will change in response to critiques of a formalist aesthetic approach, one committed to notions of modernism – that modern art is somehow better than other art that's been produced. We’ll have a very different way of looking at the material, a much more integrated way that sees an interest in the extremely aesthetic traditions as being only part of an experience of the whole. It won't matter even that one perceives aesthetic qualities where they weren't thought to exist; one will also have alternative viewpoints on the value of the material as a whole.

Other things will seem more important than the argument of form. Although I feel that if you give people twenty photographs and they pick out one as being interesting, it is formal reasons why they select one over another view of the same subject, and that therefore, within the visual arts, formal aesthetic qualities do count.

ACP: Let's turn to aspects of contemporary work. The recent interest in manipulated imagery here presents itself as being fairly experimental, although it followed similar developments in America. How much of this work in Australia do you think has been genuinely innovative?

Gael: I did a 'Project' show, Reconstructed Vision, in 1981 in which I looked at a whole area of work that seemed to be a new development in the contemporary scene. Obviously, a lot of it being so new. It did seem to be experimental. I wouldn't like to say at this stage which of that work is going to appear as interesting in fifteen years time. Perhaps I'm wary of falling into the 'train' analogy of Humphrey McQueen.

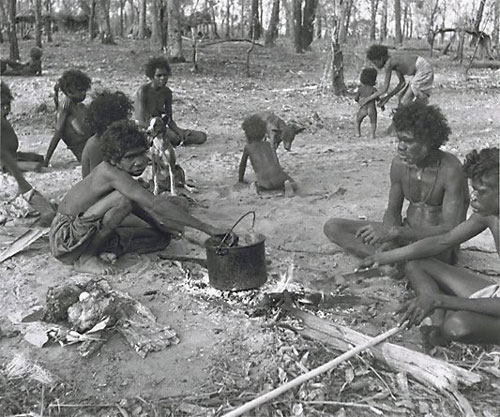

|

| Early morning, the camp 1, Liverpool River 1952, Alex Poignant, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: But to what extent was it experimental, and to what extent was it merely following the developments which had occurred in art schools in America?

Gael: It's the same story again There's been a change in the photographic climate whereby, perhaps because of research into things like Pictorialism or perhaps for other much more complicated reasons, the dominance of what you might call the purist aesthetic has been questioned.

The existence of this work here and overseas is in response to a questioning of the dominance of one approach to photography, and acceptance that the camera's a very flexible tool, and that no matter what great things have been said in straight photography, there are things that obviously it can't say, and that therefore people are now interested in exploring some of those other areas. I can't see anything indigenous about it. I think that we are responding to influences which caused us to take up Pictorialism, to take up Modernism, because we are part of a homogeneous intellectual climate. What we do in that work that might be seen as being peculiar to Australia will come as we gain strength in that new area.

ACP: Do you see that intellectual homogeneity as being a desirable thing? Do you think there's a place for development of a cultural identity, with some shared intellectual values, but which gives room for the expression of a more specific regional artistic practice?

Gael: I don't think it's true that there are no national characteristics to Australian photography, past or present. But the overall perimeters are shared with the models that we tend to look at overseas, particularly America, Britain, Europe. There's a lot of energy in Australian photography that now even seems to be of interest to an audience outside. I suspect that, in retrospect, there'll be seen to have been perhaps a flowering of Australian photography in this period that is more interesting than, say, an overseas audience might find earlier photography, which perhaps doesn't have as strong an overall character. Our need to constantly compare ourselves with overseas work will diminish. It has diminished. Even the very model of a radical elite, and our being derivatives of overseas will change. It won't seem appropriate to look at it that way.

ACP: It comes out of concern about identity as Australians that's current.

Gael: Yes. Obviously, there's an Australiana boom and I don't think it's accidental that we're approaching our bicentenary. For lots of people, the notion of being Australian is perhaps more separate now than it's ever been. There is an Australian identity but quite what it is, we probably don't know, but we all feel that it's not merely that we're provincial copies of those overseas centres. We'd be naive to think we don't respond to very similar influences. I feel a lot more supportive of Australian photography than I would have in the past.

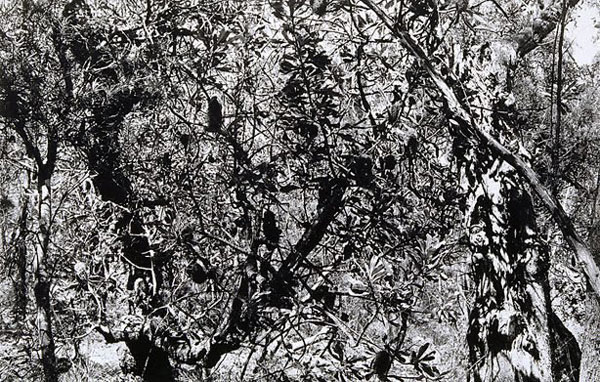

|

| Untitled: (Banskia young trees) 1979, Brian Thompson, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: You've mentioned landscape tradition never taking root here, whereas we've always had a very viable street photography tradition – maybe largely because we are an urban and surburban culture, rather than one which has a closer relationship with the land. Although one would think that being a country with such a great land area and also primary industry, that there'd be more consciousness and interest in it, but it doesn't seem to be a problem that's been approached to any extent.

Gael: Yes, but why wasn't there that problem in painting? It's still the same urban population. It doesn't apply to America – you'd think there'd have been many similarities. The role of landscape is one of the most interesting questions in Australian photography.

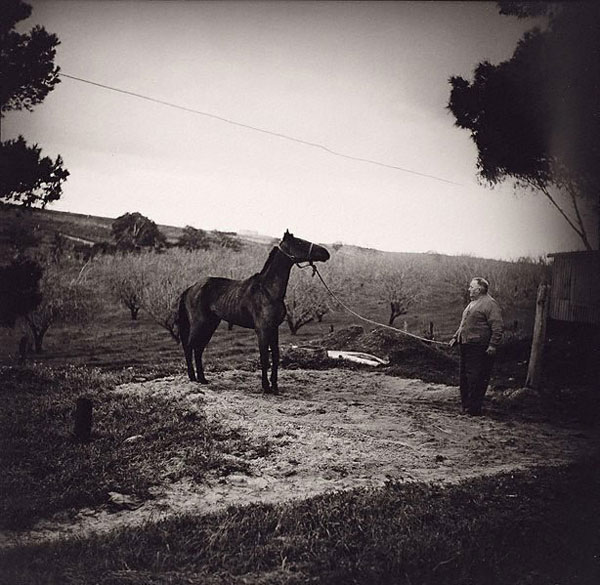

|

| Amos Chaplin, my grandfather, Gilles Plains (South Australia) c.1960, Robert McFarlane, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: I suppose the American landscape has been conquered, whereas there's not that sense of the Australian landscape being conquerable. The landscape seems to have defeated a number of earlier explorers, rather than given birth to development.

Gael: Esther Samra has done a paper on landscape photography which raises some of those questions. I feel that there's an antagonism to the landscape in Australian photography, perhaps because we did see so much of that American West Coast tradition. Finding that our own landscape was so much more austere, so much less supportive of a grand vision, a la Ansel Adams, of a nurturing environment in which to live, perhaps photographers, of all the visual artists, have carried a prejudice against the Australian landscape, until quite recently.

ACP: Would you say that the influence of overseas traditions of landscape photography has hindered the development of our capacity to see the Australian landscape in its

Gael: I hadn't thought of it like that before, because I've attacked it from the problem of a prejudice within Australia about the landscape. But it may well be possible that the most limiting aspect of the influence of other photographic models is that the subject matter – the landscape and its forms – is the area that's most different. You can take portraits, urban scenes, and I guess they're going to look the same. But the landscape can be markedly different and we've had models to follow of landscapes that look so different that we couldn't apply them.

Sometimes I've felt in looking at contemporary landscape, that photographers seem to go to a lot of trouble to find a very narrow corridor of landscape experience in Australia that most seems to resemble a West Coast landscape tradition from America. When I'm looking at the work, though I know that those landscapes exist in Australia, that it conflicts with how I genuinely experience the landscape as being much harsher than that. The fact that it might look like that in late afternoon conflicts still with the basic experience of it.

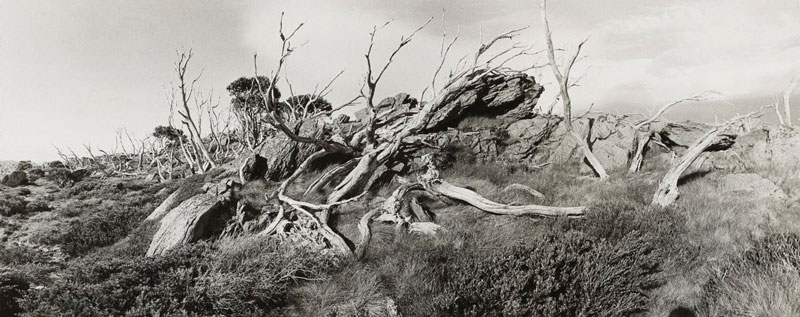

I found Brian Thompson's landscapes that he did a couple of years ago to be really refreshing because they were so gritty and had to do with the entanglement and thicket of coastal bush which I knew so well. It seemed to me so much truer to my experience of landscape than the wonderfully composed, heroic landscapes that you see sometimes, where it just doesn't relate. You don't have those viewpoints when you're pushing through the bush; you don't have large shapes in which to form a traditional photograph of the landscape – everything's very monochrome, it's very similar. The density ... it's a matter of overlapping layers.

That aspect of the bush, at least for Sydney photographers, has been a daunting hurdle. You can't get ten feet away to have a significant tree on the left and a nicely shaped rock on the right. You're presented with thicket, ten inches from the camera. You're lucky if you can even find a ten-foot space to put the camera down on with nothing between you and what you're looking at.

ACP: The landscape in a sense becomes a barrier rather than something that can be visually ordered.

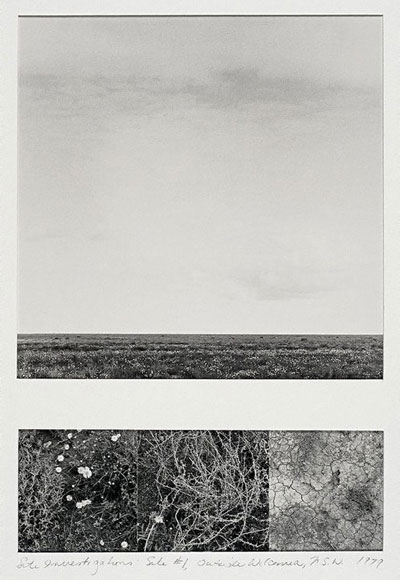

Gael: Yes. It's curious that one of the most interesting landscape works that I've seen – it was also cited by Jennie Boddington – was Lyn Silverman's 'Site Investigations' series, where there was this really subtle but strong reminder from an American photographer that what appeared to be austerity, what appeared to be eventless central Australian landscapes – and she couldn't have chosen a more desert-like environment – at her feet was shown to be a microcosm of activity and detail and enjoyment and richness.

I wondered whether that wasn't a positive statement about Australian landscape that Australians, with their heads perhaps so filled with the image of a much more fecund landscape elsewhere, didn't have the freedom to see. That is a curious thing, because that echoes backwards in time the role that American photographers played in respect of the Photo-Secession and Pictorialism. What the English and Europeans saw as desirable was the American's ability to come in and have no prehistory, no tradition, no commitment, and be fresh. Perhaps a similar thing is still working: we're carrying with us a certain interpretation of the landscape, and someone comes in who didn't have it and sees-things that we didn't see.

ACP: That work seems also to be about the scientific observation of fact, and often fact that would go unnoticed. It seems to be very analytic and contemporary in its concerns.

Gael: It's also influenced by more contemporary aesthetic concerns to do with structuralism and conceptual art. As time passes, I have the feeling that was a major landscape essay, equally as significant as Brian Thompson's. But there both quite small bodies of work. You’d be much more aware of landscape photography m Melbourne, of course, because there are people like Laurie Wilson.

I keep talking generally but I'm talking from a Sydney point of view. His length of work would seem to suggest that there are major figures in contemporary landscape photography – John Cato as well. I was particularly talking about 1900 to 1950's, where no single major landscape figure seems to exist.

ACP: Returning to the 'Reconstructed Vision* show, dealing with more manipulated imagery, you wrote that, in the end, "there were important differences in quality of craft and meaning being often overlooked by photographers." What were these important differences in quality of craft and meaning that you perceived in that show?

Gael: The Reconstructed Vision show was quite an important process of thinking out some issues, for me. I still haven't entirely digested issues that that show revolved around. I have been quite involved with the Curator of Contemporary Art in the Art Gallery of NSW, Bernice Murphy.

Through her 1981 Perspecta exhibition, I looked again at what was happening in the general art world, and the relation of photography to that world. I felt that there were a lot of things being done with photography by artists, and that a lot of photography, as a medium, was appearing in contemporary art exhibitions that suggested that there were two principles for looking at the work and it didn't seem to me to be right that you had mainstream contemporary photography not being seen or looked at in the context of the whole of the contemporary art scene. I don't think you could argue that it was being seen in that context, and I don't think the photographers look at the whole of the contemporary art scene. People might then say that that's just making photography compare itself with the existing visual arts.

But it is true that many areas of practice are very similar but are seen from very different viewpoints. I also noticed that photography was in wide use in the visual arts – in conceptual art, in documentation of performance, in manipulated areas such as silk screens and etching, where somewhere along the line, the quality of photographs or the medium was used. All that area of practice was seen as being part of contemporary art but somehow the mainstream of photography wasn't! It's a case, I suppose, of separatism versus context.

There should be a lot of looking on both sides; There's a lot of photography being used by artists nominally in other areas that's more interesting than some of the contemporary photography that's being done within the mainstream of photography, as such.

|

From Ten Small Photographs portfolio 1981, Kate Breakey,

AGNSW Collection |

ACP: What were the deficiencies that you perceived in quality of craft and meaning in the work in that show ?

Gael: That more or less specifically applies to the use of manipulation. Once you depart from the central tradition in photography of realism, of the unmanipulated print, then you invite comparison because the manipulations that you do tend to make the photograph look much more similar to certain uses of photographs within art in general. For example, if a young photographer takes up photo-etching or colours the image, does drawing over it, then I think you have to accept that you have to look at the other areas where that type of method is in use. You have to look at artists who are doing photo-etching, you have to look at silk screen prints, you have to look at conceptual use of photography, once you depart from that central and humanist tradition, because the comparisons will be made.

When you look on that level, I did find that the photography often seemed crude in technique – that may be due to the fact that so much of it is young and experimental – and that it was ignorant of other artists' work in that area that was far more sophisticated in technique and in concept. For example, looking at Bea Maddock as an artist and looking at manipulated photographs in the contemporary scene,Even given that she is a mature artist, she was using the manipulation of mixed media for a much more complicated content.

The photographers often seem to be in the photograph, content with or dazzled by the technique without really mastering it enough. The reason why they use manipulation is because the subject has to be expressed using that chord and not as an end in itself. I was hoping that that show would open a dialogue between the extensive use of photography in the contemporary art scene, in a whole range of processes and formats and approaches, and those areas of contemporary photography which are employing a similar range of processes – which is not to say that the photographers should lose all track of any separate identity that they may have, but they can't afford to be ignorant of major artists like Bea Maddock if they're going to be doing manipulated photography.

ACP: Could you discuss your policies with regard to the acquisition and exhibition of contemporary work at the AGNSW?

Gael: Obviously, when so much of our energy has gone into the historical surveys, contemporary acquisition and exhibition has suffered. The Project show {Reconstructed Vision) was meant to signal the central position that contemporary work will hold in the Department's activities now that we feel that the surveying work is largely complete. I haven't yet solved some of the problems that the restrictions on my Department, in terms of staffing and budgets, present in relation to acquiring contemporary work. We have to reconsider a policy for contemporary acquisition; it's been quite haphazard rather than systematic.

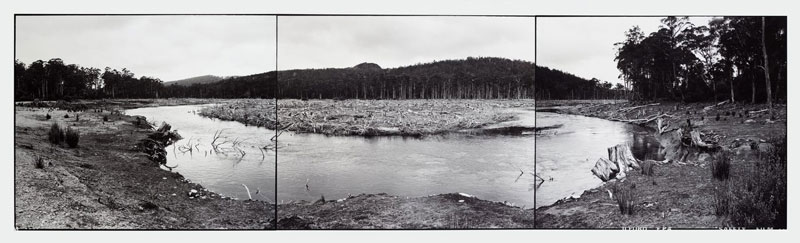

|

David Stevenson 1982: Lake King William a Derwent River hydro electric development, Tasmania, AGNSW

the above was not included with orginal article - the print by Kathyn Paul being not available online. |

ACP: What has been your policy?

Gael: Contemporary work has been bought on a much less consistent basis than our acquisition of past work. I try to keep a balance between contemporary women and contemporary male photographers, quite consciously; which is not that I feel that I've bought any work that wasn't as good as male work. Because I was buying without a really consistent direction, I knew it was important that I kept track of how many women and men were being bought, relatively, because otherwise, through accident, it could appear that I was saying that female work wasn't equal.

Given that I am in a situation where I just cannot survey contemporary photography for lack of money – I have a budget of nearly $10,000 a year, which is really is very small to perform that duty – one has to be incredibly selective. I feel now that I may have to adopt a particular policy. even a theme, to give some real shape to our contemporary collection, some identity, perhaps, to it. which will mean that many photographers who are equally worthy of being purchased may not get bought.

With the prices of contemporary photography, a $10,000 budget really is very small. I don't agree with the model of a curator as fund raiser. If there became an enormous pressure on the curator to be responsible for the level of funding of the institution, then I would quietly do my best to get out of the job – it's just not my nature to be a fund raiser.I see the collection as being at something of a crossroads at the moment, because I feel that the historical survey work has been largely completed. I do have one major project left that I think will be tremendously exciting and which is part of the contemporary scene. That is, to look at the last twenty years, to look at the immediate forbears of our own practice today, and survey in a similar fashion the sixties to the eighties.

In terms of contemporary work as a whole, a larger percentage of the budget and of my time is now free to prepare a policy for contemporary art. I still think that I'll have to choose some sort of direction, but I'm still in the process of considering what specific direction might be necessary in order to do one area rather well, rather than just proceed on a more ad hoc basis of what shows I happen to see, which virtually means, since there's almost no travel budget, what shows I happen to see in Sydney.

|

| Mythological Dream 1980 - photographic collage by Leonie Reisberg, AGNSW Collection |

I'm always buying some contemporary work, or am in the process of it, but it hasn't been the expression of a tightly defined policy – it's just been work that I felt deserved to be bought but doesn't necessarily mean that I only think those people are good out of the whole of Australia, it's often much more low-key than that. I honestly don't know how much we can do with the money that we have, whether it will be imperative to find sponsorship in order to make it a more rounded collection. One of the areas that I will keep considering is the extent to which I would like our collection of contemporary work to be un mainstream photography.

At this stage, I am very sympathetic to the ideas that I've discussed with our contemporary art curator, that the vitality of the department will benefit from looking very seriously at work produced in other contexts – artists' use of photography in a more conceptual vein, or the type of work that is seen in the biennial surveys of contemporary art, such as the Biennale and Perspecta – a range of work which isn't normally seen as being part of mainstream photography.

I would like to keep my mind very open to that work. I would also like to address the problem of contemporary work which is not so self-consciously artistic, or art – to identify contemporary areas of practice that have different viewpoints, because I think the real task for the next decade in this collection is to have a much greater plurality of approaches in terms of historical work and contemporary work, and to be much closer to the spirit of the times, which I feel are very energetically dismantling lots of concepts that have fed the collection in the past. It's going to be very exciting for that reason.

|

| Flower of the Firewheel Tree 1983, Max Dupain, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: What type of material are you interested in having donated, should material that may be of interest come to the awareness of people out in the community?

Gael: I'm always interested in possible donations, though I've become more cautious over the years about enthusiastically accepting large donations and then finding that it's an enormous administrative burden to catalogue. I'm particularly interested in correcting the imbalance in the collection of nineteenth century photography, so that, obviously, it would solve a lot of problems if someone was to come forward with a significant collection of nineteenth century photography to donate to us, or someone was to sponsor that area of the collection.

Also, in contemporary work, it would be helpful to have some form of sponsorship to make more purchases in that area, particularly more purchases of an experimental or tentative nature, like the Michell Endowment which operates for the National Gallery of Victoria. On the whole, we've had very few people walking in off the street with very interesting material, though one lives in hope!

ACP: Do you review portfolios?

Gael: I've adopted the policy of quite a few other photographic departments. It's obviously a problem that arises more with young photographers. Young painters don't tend to ask or expect the curators to view their work outside of the exhibition circuit. Because of its portability, people do tend to drag in their last ten years' work to the curators.

No, I think that, as much as I've done it in the past and I enjoy doing it, it is a confusion of my role as a curator for the institution and a de facto teacher. It does tend to be that, most of the time, you get younger work that's immature, and because you're not in a clearly defined teacher-pupil relationship, any criticism which is negative – which it's likely to be because, if the work was really outstanding it would probably be already known to you through the process of publication and exhibition in the community at large – is taken very hard, as being discrimination against them by the museum, which is confusing the two roles.

So now I discourage portfolios, particularly from younger photographers. I prefer to see work in exhibitions. The portfolios I see tend to be of visiting photographers from interstate that I might not be able to be so familiar with. I avoid comment or discussion on it, I just ask that it be left and collected. It's a self-protection mechanism, otherwise, given the number of contemporary photographers, you'd have to do for everyone what you did for one or two simply because they happened to ring you up.

ACP: To what extent can curators shape our perception of current and past photographic practice?

Gael: I would have dissembled on that question. In the past and put forward a view that the historian is more or less objectively showing what happened without reflecting a personal taste. Unfortunately, whoever is in a job colours that job quite strongly.

I don't know that there is any such thing as an objectivity, because you can't put up work that you have no confidence in. Sometimes that confidence may amount to a personal sensitivity towards some areas and a personal insensitivity toward others. Where I recognise personal insensitivity, I am now trying quite consciously to develop mechanisms for referral and consultancy with other people.

I'm concerned in principle with the way the whole curatorial profession operates, of letting one individual loose on the task of for mulating a collection. I don't think that's because I don't have confidence in myself; I'm just concerned that, as a principle, it seems to leave a lot to be desired. I certainly know that many curators, like myself, really have a very free hand – outside the constraints of budget and the conservatism, perhaps, of an institution -– in where they take the collection. Perhaps you just have to live with that. I am in a very experimental frame of mind about ways of doing things differently from the way they've been done, without ending up having no central direction to the collection. I think inevitably, you also have the right to bring your strength to a collection, even at the cost of other areas.

It's something that's occupying a lot of my thought at the moment, but my most pressing demand is to diversify the collection, and that includes humble snapshots, right through to performance art documentation.

|

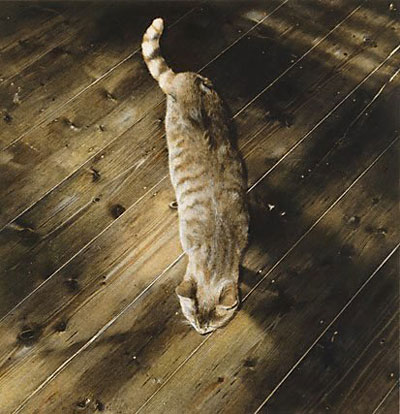

| Father and Child from the Walking the dog series 1983, hand coloured by Robyn Stacey,, AGNSW Collection |

ACP: Many women have gravitated to arts management as a career. Is there any particular significance in their being a preponderance of women in these positions?

Gael: I think it's just, mechanically, a reflection of the fact that so many more women go to art school and do fine arts courses, because it seems to be more socially acceptable. It's almost a reflection of a rather Victorian model of 'nice accomplishments for women'. I've always taken my art history incredibly seriously and always wanted to work in art history. Even by the time I was fourteen, I knew that that was what I would want to do. I don't think I've been quite as affected by that. Certainly, it's true that art history courses are full of women, because I think women are free to consider that area, whereas a lot of men still feel that it's a bit like taking up ballet dancing!

Then, of course. the other end of the spectrum, which is so unequal, is that the men who do take it up seem to have an extraordinarily high likelihood of ending up in charge of it. There are lots of women curators; there're still not too many women directors. I think perhaps sometimes the notion of the profession is often coloured by that notion of lots of girls doing art at art school but not becoming painters! But I think that situation has probably ended. I don't think girls go to art school now under those kinds of pressures to do something nice and safe for a while.

ACP: It depends on how old they are, and where they're coming from.

Gael: I think that at times, the fact that I've been a woman has affected the way people view the collection. I've certainly been aware of it even in dealing with photographers; there's been a slightly less than serious attitude, sometimes quite markedly so. I suspect that perhaps, occasionally, from time to time, even the institution would have thought more seriously of what's being said or done if it was coming from a mature curator who'd been around a long time, who was male. It hasn't greatly affected my role, but I have been aware of, at times, that general attitude of 'it's nice for a woman to do something like that!' affecting it.

I have to admit that I do perceive an aesthetic of my own, that may have something to do with my being a woman, at work. Particularly since I've had a child. I feel that I look at things differently now so that it must affect the types of choices I make. I see the world as rightly concerned more with humanism than before.

ACP: Would you have any suggestions for people now who may be interested in starting out on a museum career?

Gael: The situation today of course is very different from when I started, when there were few people interested in curatorial positions in photography. In fact, there was a slight feeling that you were a failed academic, and a curatorship was a soft option, whereas now curatorship has almost become a very glamorous profession.

A lot of people are very interested in exhibition work. I suppose this reflects a very important change in photography. When I was at art school doing photography, the documentary tradition was still uppermost, and therefore you were still primarily interested in publication of your stories in magazines, or perhaps in monograph publication on your collected work. Now Ithe focus has completely shifted onto a really conventional art model, where the exhibition is everything, and no one is very interested in communicating their work through the old methods of getting work in photographic magazines or into photo-reportage. That's to be deplored, because art galleries are much less accessible places, really, than the photo-reportage model.

But there are a lot of people interested in museum work. The main problem for people going to art school is that they will have to acquire academic skills in writing, because writing is so much a part of curatorship – people forget that. There are constantly reports to be written. You have to be able to churn out a piece of properly written research work. Therefore, you need research skills and writing skills. However, people are terribly resourceful too. People that you think couldn't do that work because they had no background in it . . . I've seen them learn quite quickly.

There are also a lot more job opportunities in museum work. The main thing is that you need to be educated about the whole of the contemporary art world if you're going to go into a museum. You can't function in a vacuum. I guess you have to attend exhibitions, become informed, start at tending openings, making contacts, trying to do a bit of writing and getting it published, or trying to do a bit of research, trying to present an exhibition on some modest scale – something that can show what you can do.

There are a lot of people applying now. and any small difference in terms of what you have to offer, or what you've done on your own initiative, will count. I've had a number of interns work for me, I think all of whom have gone on to jobs in museums. Obviously, the experience they gained in seeing how a museum worked from the inside was very valuable. There are some problems in having voluntary interns, because you're obviously dealing with people who can afford, for some reason, to give you that time.

Democratically, it would be better to have a formalised system where more people had a chance. But, given the nature of the profession, the people who are interested have already gone through a fair amount of background work. The most pressing thing. For curators of photography is to decide what their relationship is to contemporary art practice, and how strongly they're going to fight to have contemporary art re defined to incorporate the photography that doesn’t seem so like the rest of the arts.

Below are a few extra photographs from the era - these were not part of the original article.

|

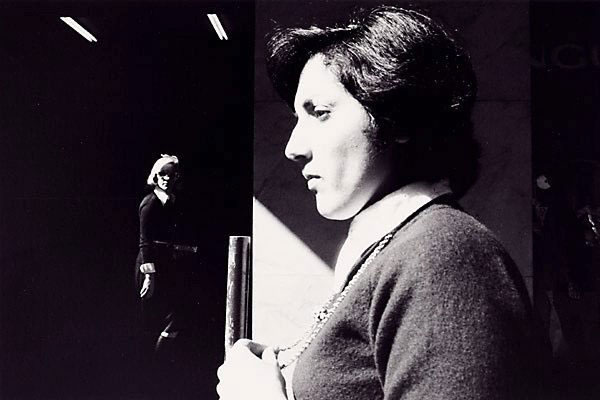

| Christine Godden 1980: John Delacour's picture, AGNSW |

|

| Ingeborg Tyssen 1982: Tucki Tucki, NSW, AGNSW |

|

| Ingeborg Tyssen 1977: untitled, AGNSW |

|

| Ingeborg Tyssen 1984: Perisher Valley no 7 NSW, AGNSW |

|

| Lynn Silverman, 1979: Site investigations: site #1, outside Wilcannia, New South Wales, AGNSW |

|

| Micky Alan 1980, Banksia, Mountain lagoon, AGNSW |

for more on Gael Newton AM - click here

>>>> more on Photography and the Curators (links to pages on some of the first curators of photography in Australia)

|