1983 Interview between the Australian Centre of Photography

and Jennie Boddington (1922-2015)

Jennie Boddington was the first curator of photography (1972-1994) at the National Gallery of Victoria, NGV (The state art gallery for Victoria, Australia)

She was interviewed at The Australian Centre for Photography by Mark Hinderaker and Mark Johnson on 15th February, 1983.

In 1972, the National Gallery of Victoria became the first art museum in Australia to establish a permanent photographic department.

Jennie Boddington has organised its activities since its inception, initially as Assistant Curator and subsequently as Curator. Her outline of the Department's history was published in "Photography in Australia" conference papers (Department of Adult Education, Sydney University 1977).

ACP: Jennie, can you tell us something of your background before you became involved with photography?

Jennie: I was a film-maker for 25 years. When I left school, I was mostly interested in literature and started a university course in English and History, but the war came and I never finished the course.

I became very interested in documentary films during the war. After the war I moved from Melbourne to Sydney because there were no film jobs in Melbourne. I went to work in what is now known as Film Australia where I trained mostly in the cutting room because that was all that was available to women at the time. And I eventually was making, scripting, directing and editing films for nearly 25 years. But I don't think there is much relationship between cinematography and still photography.

I worked with my husband from 1957 onwards, we were self-employed and we made sponsored documentary films. During that time, we made a film that received a lot of attention and I mention it because it is a reflection of my interests still. It was dealing with the problems of migrants in the community. This film was actually made for BP, the petrol company. We had a fair degree of freedom in the making of the film and it was an early attempt in the medium of film to come to grips with real problems in Australian society, particularly in one segment, which was the main story as far as I was concerned, about the loneliness of the young Italian migrant in Melbourne. This is going back to 1958-59.

We continued to make sponsored films of various descriptions including a very interesting one which was scripted by Cyril Pearl, on the history of the Gallipoli campaign which was done entirely from still photographs out of the National War Memorial archives. We generally preferred these more unusual kinds of jobs to doing things for big companies. We did quite a few for the Anti-Cancer Council and the hospitals and charities commissions in which it was possible to come to grips with social issues, and these were the ones that I enjoyed most.

Eventually my husband died and I had a young family and the film-making was much too arduous to be able to keep on so I sort of withdrew from it. I didn't know what to do with myself. It was difficult to get a job and I had hoped to begin writing, but I don't think I had the discipline, and I certainly had to earn a living.

Adrian died in 1970. He was a still photographer before he came to movies. He was with the Argus Newspaper for a time, he trained in the Airforce, went to the Argus Newspaper and then was self-employed. In fact, for years he did the publicity photos of all visiting celebrities for the ABC so there are some very interesting portraits tucked away in their artists files, but it would be difficult to track them down. That material is lost to us, but it's there in the ABC somewhere.

So, I was having trouble finding a job to support my children and someone told me that the National Gallery of Victoria was setting up a photography department and would I be interested in it. I was extremely interested, because I had become, over the years, rather interested in still photography. I suppose I knew very little about work from overseas. I guess I had a familiarity with the Farm Security Administration and with Cartier-Bresson's work and such people, whose work I had seen in reproduction in books, but I really knew very little about the subject.

I did apply for the job and I got it.

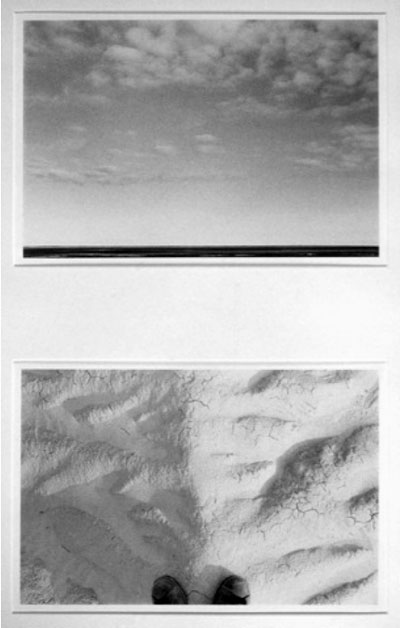

|

| "Lake Mungo (looking westward), 1979" from "Horizons'* by Lynn Silverman. Collection: National Gallery of Victoria. |

Those early days were of course terribly, terribly difficult. It was an enormous challenge to come into an established art museum, some of whose curators didn't think that photography had any place in it. I must say they were co-operative and supportive.

By 1975 we had the top floor, which had been a storage space leading to administrative offices, made over into a Photography Gallery and since then there has been a consistent series of exhibitions run by the Department of Photography.

At that time the photographic sub-committee was phased out so the department became autonomous and from then on had to stand or fall on the basis of my judgement. That was the time at which I became supremely interested, because I liked the feeling of having the department relying purely on myself... bit egotistical perhaps, but I enjoyed that...

When I got to the NGV I had to learn a great deal in a short time. In those days there was, and still is, a lot of confusion about that terrible word 'art' as connected with photography. I have to admit that I was just as confused as everybody else and I certainly purchased things in those days that I wouldn't dream of purchasing today.

I think that it does take some confidence to come through to an appreciation of photography as itself, for its own unique, graphic capacity to convey what often one would think of as merely information, where actually it is a hell of a lot more in the hands of a master or even a very good practitioner. So that I'm inclined, the longer I'm there, not to take heed of the word 'art' in any shape or form.

ACP: In your documentary film-making were there other people, internationally, that you looked to with interest in the area of documentary film?

Jennie: Yes, I suppose one of the documentary film-makers that I most admired was an Englishman called Humphrey Jennings who unfortunately died when he was only 31.

He made a film during the war which was called "A Diary for Timothy" which was made I suppose to boost the morale of the British in a very difficult time. The commentary was spoken by Michael Redgrave. This was simply a film which portrayed the English at war but in doing so he very skillfully and sensitively reproduced some of the proudest things out of England's cultural and scientific history.

Again he did a similar kind of film, called "Family Portrait", which was made for the Festival of Britain. I found his films extremely rich indeed.

ACP: Prior to your interest in documentary film you said you were interested in literature. What form would that interest have taken if you had made literature the basis of your career?

Jennie: Well I suppose the writing of fiction. But if I was to start writing now I wouldn't be trying to write fiction.

ACP: Walker Evans came to photography through literature.

Jennie: Yes. Can I read something from Walker Evans here, as it perhaps helps explain my views on photography? In an interview he was referring to having been influenced by Flaubert and said "his realism and naturalism both, and his objectivity of treatment, the non-appearance of author, the non-subjectivity. That is literally applicable to the way I want to use a camera and do". Another thing he said was that he "wanted to operate against mediocrity and phoniness."

ACP: That's certainly something that would relate to documentary film. The sentiments come from the same period. You would have been aware of a lot of the social problems during the Great Depression. Do you think that experience predisposed you to an interest in a more factual approach?

Jennie: I was at a rather protected boarding school during the Depression, so I didn't really notice it. However, later on I became interested in the whole question of the social history of Australia.

ACP: You've had a lot of contact with 19th Century and early 20th Century material. How do you think historical images are of value to contemporary photographers?

Jennie: The whole of culture is a matter of handing down, of continuity from one generation to another. Therefore I think our historical photographs are of great importance. I regret that tertiary colleges don't make more use of early Australian material. They take modern American material for their teaching, to the cultural confusion of the students. I think there is a tendency to narrow it right down just to modern American, even to ignore a lot of European material.

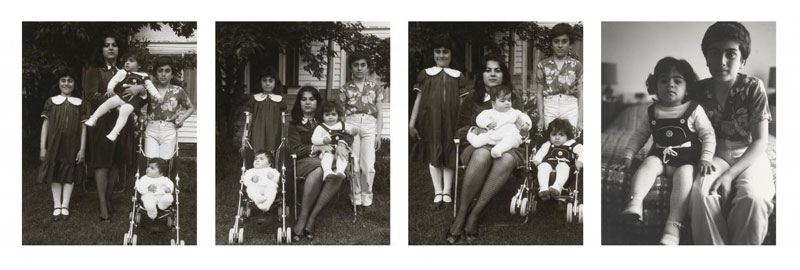

|

| You can't go home again" by Jillian Gibb, 1983. |

There was a great fondness for a time in Melbourne of Diane Arbus' work which was deeply misunderstood and horribly imitated - that seems to have gone at last, thank goodness. Now, I think there is still a strong Ralph Gibson influence going - bits and pieces of figures that don't tell one anything about anything in the photographs.

It's the modern Pictorialism, the desire to give photography a kind of ‘art respectability', and as it's taken superficially from outside and doesn't come from within the photographer's interpretation of the subject, it's literally meaningless.

Yet we all know a lot of students go through these imitative periods - there's no harm in that, it's just that it shouldn't be taken too seriously.

ACP: Do you think this is a function of the way the history of photography is presented? The publication of histories of photography is dominated by America and Europe.

Jennie: Yes. There is so much American material available that naturally it comes to be used. Everyone has to have a sense of his or her own identity, and I think a sense of cultural identity is a part of personal identity.

I used to think that overseas work must be better than early Australian work, but I no longer think that. In fact I'm convinced to the contrary. Maybe some of it's better in quality, but that's not the final way of judging cultural material. I'm quite sure that a lot of extremely interesting photographers will come to light as time goes by. We still now have material that is known in libraries, but not aired or reproduced. The libraries tend to be understaffed, compared with the art museums.

ACP: What can we do to prevent this over-valuing of overseas traditions and the comparative undervaluing of Australian work?

Jennie: To continue what we're doing now, which is energetically to try and bring to light Australian material of interest and to keep on exhibiting it. It would be very nice if someone could publish some of these very interesting workers. I've seen albums in public library collections all over Australia which contain absolutely beautiful photography.

We have one in our collection which was produced by the N.S.W. Railways in honour of the opening of the bridge over the Hawkesbury River. The material in that is exquisite: marvellous big prints of small villages and settlements, half-cleared farms - you really get the feeling of these struggling, small farmers trying to hew their farms out of the thick bush.

ACP: What are the ways that tertiary students could be better informed? Access to material for teaching early Australian photography is simply not there.

Jennie: Absolutely. It's extremely important to realise the artistic worth of material held in library collections. Much of this is not sufficiently in order to be made available. Staffing for this and for education and reproduction is a high priority, I think, a crying need in the country.

ACP: Since we don't have magazines or books publishing this material, probably slide sets would be an important thing.

Jennie: I think probably that's where it has to begin. I would hope for publication in the future with the very best standards of reproduction. 1 can't see that anything less does justice to photographs.

ACP: Apart from the historical interest what do you think are some of the visual and photographic qualities to be found in 19th Century works?

Jennie: If I find work interesting, I think it's usually because it's very assured, a very assured use of photography in whatever style it may be. I take the art content for granted when I'm talking about the interest of the material.

For instance, J.W. Lindt is a very great Australian photographer who devoted the last years of his life, when he went to live up at Blacks Spur, not far from Melbourne, in the rain-forest, to making very beautiful, stunning photographs in this rain forest. We have about 25 of his big prints, which are absolutely perfect in their tonal range - and they're absolutely permanent.

But I don't feel they're nearly as interesting as a fairly big body of his material that has come to light in the Latrobe Library in Victoria. There's a kind of noble certainty about every camera set-up that he makes. When he's dealing, as he is in this material at Latrobe, with our everyday, colonial society, the work is of enormous interest.

I like to think when I judge any work to come into our collection about how it's going to look fifty or a hundred years from now. And if it's just a picture of someone's navel, it's not going to have any interest at all, is it?

ACP: How would you evaluate in those terms the work of the Pictorialists who were active at the turn of the Century. Their work is not very specific in terms of its cultural connections.

Jennie: It's only specific in that they're yearning and dying to be artists! One gets tired of the oppressiveness of Pictorialism because it went on being practised for such a long time.

Certainly, I think some of Cazneaux's stuff is really beautiful. Also, some of his work is very radical. So is some of John Kauffmann's. These are people of such stature that they come way above the general run-of-the-mill of Pictorialists.

John Kauffmann was the most radical of them really. Some of his pictures are reduced to just, say three tones.

ACP: In Kauffmann, there seems to be a willingness to deal with the 20th Century, incorporating cars and so on.

Jennie: Yes, but Kauffmann's most radical work was closely directed at pictorial abstractions. Some of his scenes by rivers and tree studies were very experimental works indeed. Me the anti-pictorialist!

ACP: To look at Kauffmann, there is that element of Australian light. The early pictorialists were criticized for the harshness of the light when they sent their prints to international salons. Do you feel that Kauffman is attempting to deal more with what's actually here?

Jennie: Not in the specific part of his work that I'm talking about. I think even he tended, in his more lyrical pictures, to get that kind of diffused feeling about the light. I think the pictorialist who best achieved, apart from Cazneaux, that quality of the Australian light, was William Thomas Owen.

After he came out from England, he really tried to come to grips with the Australian landscape through places like Beaumaris beach around Melbourne. You do get this feeling of a blinding quality in the light, and later, in the best of his farm studies, a sense of the small farmer, struggling out there in this harsh light.

ACP: What would be the value to contemporary photographers of being aware of Pictorialism as an aspect of photographic history in Australia? Is it merely a curiosity, or a warning or...?

Jennie: Pictorialism will subside into its place better as more of the other material comes to light, I think. There must be huge bodies of material by country professional photographers. I have seen some by a man called Adolf Verey, of Castlemaine, Victoria, which is among the greatest photography that you could imagine. A private collector has bought 10 thousand glass plates by this man and I'm afraid they're being held onto. That's fine, so long as the best of the material does come to light eventually.

Portraits of great presence, marvellously informative too. These are portraits of people outside their own houses -old women in cottage gardens, married couples with their children outside their bigger houses. In group portraits in small factories, the remarkable thing is that every single face in its entire difference just springs out at you.

There's a portrait I'll never forget of a young girl of about 13 years with long, pointy black shoes and black stockings and a white dress on and a big hat, and she's holding, I think, two ponies, one on each side of her. It just shrieks at you, like reading a marvellous passage from Proust. This work was done from the late 1890's to about the start of the First World War.

There must be more material like that. I don't see how Pictorialism can remain more obvious when more material like this, and of such quality, comes along. Things will then assume a better relationship.

ACP: I suppose part of the interest in Pictorialism is that it claimed a legitimacy as fine art

Jennie: Well, that's all. I just find it less interesting because it is overall so repetitive.

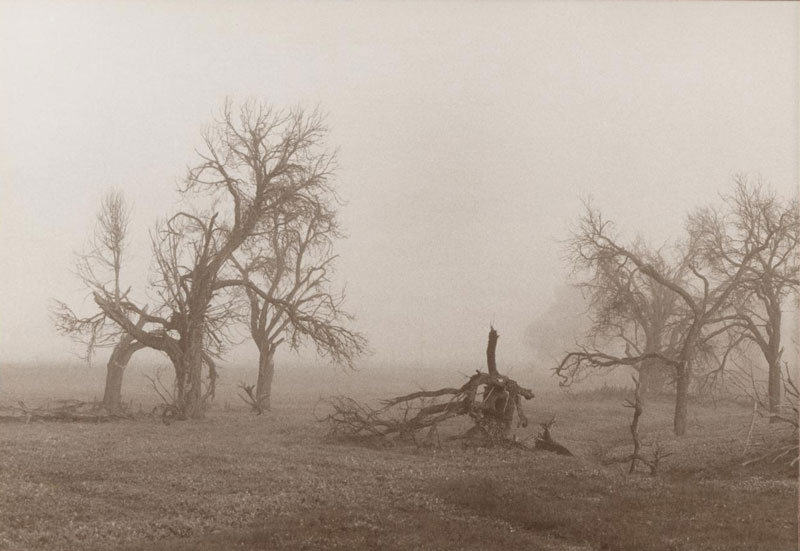

|

"Prof. Leopold Korensky with his wife & children, Linz, Danube 1906" by August Sander.

Collection: National Gallery of Victoria. |

ACP: In the U.S.A., and less so in England, Pictorialism has been widely received in the last decade as part of the tradition which precedes a more contemporary image making that uses manipulation of photographs.

Jennie: In America, they're very much into investigating the aesthetics of photography. I suppose I'm more interested in the cultural material. Pictorialism does belong specifically to the aesthetic history of photography, just as I think Weston's work does, whereas I think Walker Evans belongs to the whole culture, hence Walker Evans' enormous importance.

ACP: Do you think the medium is at its most significant when dealing with the world in a fairly straight-forward way?

Jennie: I personally am deeply interested in photography that deals with the world as it is. But it's the success that the result achieves that's the important thing, so I'm not altogether insistent on this.

Think of some of the wonderful, witty pictures by Sudek, where he's put a glass eye on a white wire chair in a garden or something, and has made a most magical picture. Look at some of the beautiful still life photographs we've had, which are in every way arrangements.

Look at Marie Cosindas' beautiful Polaroids, which are unlike anything else in photography and which probably stem more from painting than anything else. Because these succeed so wonderfully, I don't have any argument with them.

ACP: Jennie, you've mentioned the need for fine reproduction of photographs in publications. If a photographer's work is published to this standard, what can we still learn from an original print in an exhibition? Do original prints have some intrinsic relation to the artist, comparable to original works in other media?

Jennie: Yes, and that doesn't mean that I would write off modern prints from early negatives, if they're done with great respect for the photographer's original intentions, and the manner of printing of his period.

Recently, I put up a retrospective exhibition of work by Laurie Wilson, who died in 1980. This was the selection of work published in a book the Gallery has just completed on this man's work. From seeing the printed reproduction on the page, I was able to go out into the gallery and see the original prints hanging on the wall.

Certainly, the original prints have a quality which is quite other from that of the flatness of ink on paper. There is a kind of relief, a sparkle to the original prints which is quite an exciting and very personal ingredient put there by the photographer himself.

|

| .Unidentified photograph by Laurie Wilson. Collection: National Gallery of Victoria. |

ACP: Could you talk a little about any special problems a museum photography department faces, for example, financial?

Jennie: I can't say any longer that the Photography Department is financially discriminated against. The whole thing has tightened-up over the last couple of years but I can't say I'm any more discriminated against.

In fact, only a couple of months ago I was able to procure a purchase through the Art Foundation (which is the major funding body) when I bought some material of the 1850's from British photographers working in India which was a very expensive purchase!

ACP: What sort of balance do you strike between exhibitions you curate and travelling ones you obtain from elsewhere?

Jennie: I do far more from the collection because I think it's only fair to the public to be able to see what we're buying, and where we're going. Where I like to strike a balance is between international material or early material and modern material, between Australian material and international material. Because in recent years more overseas material has been shown in Melbourne than ever was hitherto, I've been able to show more work in more modern Australian fields.

ACP: In deciding about exhibitions and acquisitions, what relative weight should curators give to their own judgement, versus a perceived prevailing opinion, if these differ?

Jennie: I just use my own judgement. I do try very seriously to get some kind of a balance about modern Australian representation, at the same time not trying to take in too much, because I think one's judgement is better made a few years off. At the same time, I want to get material from overseas.

Because of the advent of the A.N.G. collection in Canberra, I usually consult with Ian North and compare notes. I also tend to buy much earlier photographs because Canberra has bought a lot of modern work. It's getting very expensive, and it's possible to get exhibitions together from different institutions - loan material.

ACP: Do you think photography is subject to the vagaries of fashion?

Jennie: Undoubtedly it is. It is bound to happen with an important artist, that he changes the way you look at things, and the imitators come thick and fast. Friedlander is one. Frank is another, and so is Diane Arbus. Thank God the Diane Arbus period has gone away, because she was the most misunderstood of all.

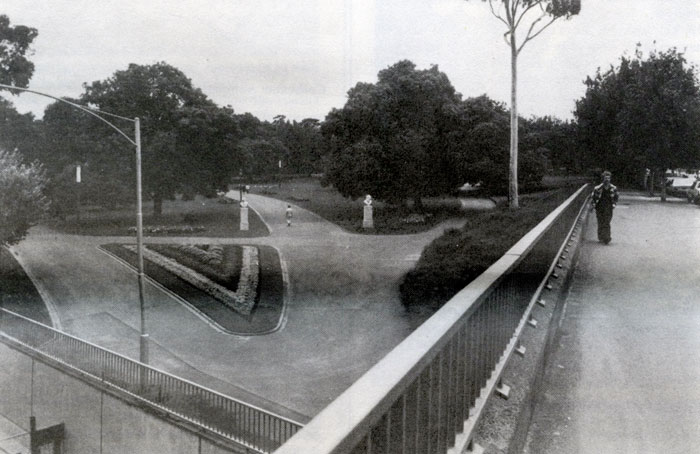

|

Melbourne, 1977 by Lee Friedlander. Collection: NGV

This image was not used in the original publication |

|

Melbourne, 1977 by Lee Friedlander. Collection: National Gallery of Victoria.

This image was copied from the orginal ACP newsletter as no image was available online |

ACP: To what extent do you think a public gallery should support contemporary artists through purchases of their work?

Jennie: I think perhaps it's better to support contemporary artists by exhibiting their work. I think the ideal situation is to have a kind of holding collection of contemporary work which is perhaps under a separate roof or in a small subsidiary organisation and from which the cream can be put into the permanent collection after a time has elapsed when one can better see the value of material.

ACP: Do you collect contemporary work along certain themes? How do you decide to add a contemporary work to your collection?

Jennie: Again, out comes the old phrase: cultural relevance! If a work really grabs me, as did, for instance, Ruth Maddison's work some years ago, "Christmas Holiday with Bob's Family", which is a moving, profound picture of a certain kind of lower middle-class Australian milieu.

It deals with a Christmas holiday among this family in Queensland. It's hand-coloured; it's a remarkable work because it is about life and death as well as about a Christmas gathering, the Christmas tree, the blokes with the tinnies, a very funny game of badminton, the picnic in the heat and the slightly off, whacky hand-colouring.

I desperately wanted this work and it seemed criminal to break it up and make a selection from it - there are 27,1 think, small pictures - so I bought the lot, and put it before the Trustees, who were affronted. They couldn't bear it. To them this was not art at all. So, I was called into the Trustees meeting, which was very unusual, and I had to support it. They agreed in the end that I could submit it again at another meeting after getting another opinion. got Les Gray's opinion and it was bought.

ACP: Would you like to comment on the extent to which Trustees should be able to over-ride curatorial decisions?

Jennie: One gets to know the system with which acquisitions are made and I think it is up to one to do it in such a way that they don't get knocked back. So far, I really have had only one thing totally knocked back, and that was some snapshots!

ACP: Can photographers leave work at your Department for assessment and feedback?

Jennie: Yes, but I prefer not give any feedback. I know that the Museum of Modern Art in New York absolutely refuses to give opinions on the work it views and I generally follow that precept. That may sound very bad, but I used to feel very plundered by this duty, because if you aren't responsive to someone's work, it's a dreadful feeling to have them sit there dragging the marrow out of your bones.

Someone might go away who isn't necessarily showing me bad work at all but just work to which I'm not responsive. I don't think it's something that ought to be put on curators to advise people about their work.

ACP: What other sources of feedback do they have in the community?

Jennie: How important to them is this feedback? I feel that if they're doing it and they really believe in it, they're going to go on doing it anyway. Is it a responsibility, for someone who is quite untrained as a teacher, to discuss all the work that comes in? One naturally follows up or purchases work one admires and from then a working relation is set up.

ACP: What effect do you think the recent expansion of photographic education in tertiary institutions has had on photography?

Jennie: It has certainly made for a better-informed audience, and for a much more skilled practicing of the craft of photography. However, I think that photographic education over the last 8 to 10 years has literally exploded, and perhaps the rocks that have been swallowed are a little undigested.

There is an evolution that is desirable. Most people aren't set in what they think it's right to do. Sometimes I think they're too "unset" in that they're always willing to change their minds. It's like a kaleidoscope going before the students' eyes.

I just regret that there isn't more use, as I've said before made of Australian material and much, much more reference to it, and a kind of instillation of a sense of cultural identity. I find by and large - but I might be over-generalising as I don't know a great number of students - that there is a glib acceptance of what I would regard as some of the more meretricious aspects of modern American photography, combined with a lack of interest in their own specific culture.

This generally speaking doesn't apply so much to the women, who seem to have a strong sense of working within their own culture and about issues, sometimes connected specifically with women, but often with our own culture.

This certainly applies out in the wider community among practising photographers. I'm thinking of the work of such people as Ruth Maddison, whom I've mentioned, and Virginia Coventry who has done a very ambitious work on the town of Whyalla, which she has photographed, with extreme care, in great blocks, so that she can build up big composite pictures of this really artificial settlement, set between desert and sea, which is a BHP town.

Also, the work Lynn Silverman has done in Australia has been very interesting and Australian. There was her early work on the western suburbs of Sydney in which she took 13 equidistant viewpoints in a street and photographed looking into each side of the road from each viewpoint. One side was the railway line going off to Melbourne through paddocks, a loose kind of agglomeration of semi-industrial buildings, straggly trees, and on the other side a row of typical Sydney western suburbs blocks of flats. That is a fascinating work, a very linear, precise kind of work. The quality of the prints is such that they require close attention.

JILL GIBB

The work of Jill Gibb is, I think, some of the richest that's being done in this country at the moment. She has a great inner strength. She uses prints that have quite a luminous quality. She's very interested in the people in the inner city of Melbourne who live all around her, who are merely temporarily living, in these now very valuable Victorian small houses which they've rented for years and years.

They live there with their pet dogs and things. She does shots of them, shots of old pensioners in the local coffee shop or in the barbers, shots of black immigrants and their loneliness in the community. She's also very interested in the country - she was born in the country. She has a great sense of sacred Aboriginal places. What is happening in the country now - there's one work called 'Dreams of Manila': a farmer dreaming of getting a nice young wife from the Philippines, which indeed he did; and a later work of him with his young Philippine wife and their baby - and he's holding, incredulously, this little snowy, squirming parcel.

These are fascinating, very rich works indeed - deeply aware, and political - usually in assemblies of anything from 2 to 5 prints side by side.

ACP: Do you think this concern with the social environment is more marked in Melbourne?

Jennie: I think it might be amongst the older, more consolidated photographers. Although I do instantly recall the work of Michael Gallagher in Perth, who has become passionately interested in the whole Aboriginal question. He began by taking photographs of the fringe dwellers around Perth and these include some of the most magnificent and moving portraits that I have seen.

He also went up to Noonkanbah and lived with the Aboriginal community when they were having their convulsions of history, and their confrontation with the police there. Whilst he was working under very difficult conditions at meetings, and with things happening, and confrontations between blacks and whites, he nevertheless always retained his artist's eye.

Each photograph stands on its own, which is quite remarkable when you're working in that milieu.

ACP: How well-developed a tradition of landscape photography do you think we have?

Jennie: I think there, we come across the question of work that's yet to come to light, but I do think there has been quite a strong tradition of Australian landscape photography. A lot of people now are making some very beautiful landscape photography, in the American mode. A lot of photographers are becoming interested in using colour, and a lot are becoming interested in panoramas -whether as single prints arranged side by side or as straight panoramas.

We have of course that endless middle period of Australian landscape photography, in which the landscape is depicted in a rather serene, romanticised way. I suppose that's vaguely related to the Pictorialists.

We do have the best of the Pictorialists - again, much of Cazneaux's work and William Thomas Owen, who's been often overlooked, I think, but whose work I recently came to re-evaluate by simply looking at it more closely, and found it to be a strong, valid contribution to Australian photography, of the small farm milieu in Gippsland. He gets a feeling for the hot landscape, the folds of the landscape, the kind of light, the very empty skies.

J.B. Eaton is another one from that middle period. Then of course you have a huge amount of material from the nineteenth Century, from all parts of Australia.

We've hardly mentioned the work of professional working photographers. I think this is a very interesting body of work yet to be recognised. We were recently donated a large collection of work by Edwin Adamson, a working professional photographer who started in Melbourne in the 1920's and went right through to the Olympic Games in 1956.

He is one of those indomitables of the pre-specialisation days. He did fashion, industrial, architecture - anything that he was paid to do. So, we have this immensely interesting body of work which reflects the mores, the taste of the period, fashions -in prints that are superbly crafted. Even some hand-coloured industrial portraits of welders at work, people at work in foundries. It seems such a contradiction to have that kind of work impressionistically hand-coloured.

ACP: What can we do to increase the interchange between living commercial photographers and people interested in photography from the more artistic point of view, so that their work can be more widely seen?

Jennie: I am in touch with some of the commercial photographers working in Melbourne. I'm interested in that field, not so much in the present day, as a matter of fact, because I think a lot of the work has become so glossy and de-culturised, so that it's no longer of any interest, except as photographic perfection. But there are those who, while not being first-rate artists, because they are first-rate journeymen, reflect the middle culture of the days through which they're working. That's what Adamson is a very good example of.

ACP: The ACP is at the moment fostering discussion on desirable future directions. What activities do you think the ACP should develop and do how you think we could improve the services provided to people outside Sydney?

Jennie: It would be desirable if, as you all know anyway, it was to get a very wide range of work together and not to get too stuck into just the art of photography as it is practised by a few privileged people in a kind of minority. It would be nice to see the Centre being able to be at the centre of a distribution system of exhibitions which could travel all over Australia. There are new galleries which haven't had interesting exhibitions of photography in the past, which perhaps now have room for them.

There could be a really good pooling of material from different collections, and a chance for different curators to put together exhibitions on themes that interest them, and have those exhibitions toured. All of this means funding, of course. I don't think it should reflect just the concerns of the serious art of photography, but all kinds of cultural concerns. Not necessarily showing only modern work either. My great pleasure, in my work, is to see an exhibition on the walls which is really popular.

ACP: Which have those been at the National Gallery of Victoria?

Jennie: Well, the Antarctic photographs of Ponting and Hurley, the press photography exhibition, the N.A.S.A. space photographs. I'm sure the present show by Fred Kruger will be another: Victoria in the 1870's and 80's, of all these places that are still easily recognisable and yet have changed so much.

Laurie Wilson's work is always widely received - it is so expressive, it seems to hurl itself off the walls at people, and get to them. The exhibition done years ago by David Moore of Henri Mallard's photographs of the building of Sydney Harbour Bridge.

I try to keep a very broad range of concerns going in the exhibition program. For instance, I'm planning a show now of work by a man whom I met through giving a talk to a camera club, who all his life has been crazy about configurations in the sky, and from a very early age began taking photographs of clouds. He became very interested in professional meteorological matters - his photographs have been used in meteorological charts. He worked as a bank accountant, or something. He's now retired and is filing his collection. No one's ever heard of him. The work is superb.

ACP: We're very grateful, to you Jennie, for giving us the opportunity to interview you.

>>>> more on Photography and the Curators (links to pages on some of the first curators of photography in Australia)

|