Jack Cato Main Page

Biography

Ian Cosier's 1980 Thesis on Jack Cato - adapted for online 2020

Notes on this 2020 version: This biography is based on 1980 Melbourne University Fine Arts These by Ian Cosier.

There has been some updating, corrections and substitution of images if the original could not be identifed. In a couple of cases suitable quality photos are yet to the found, so replacements were used.

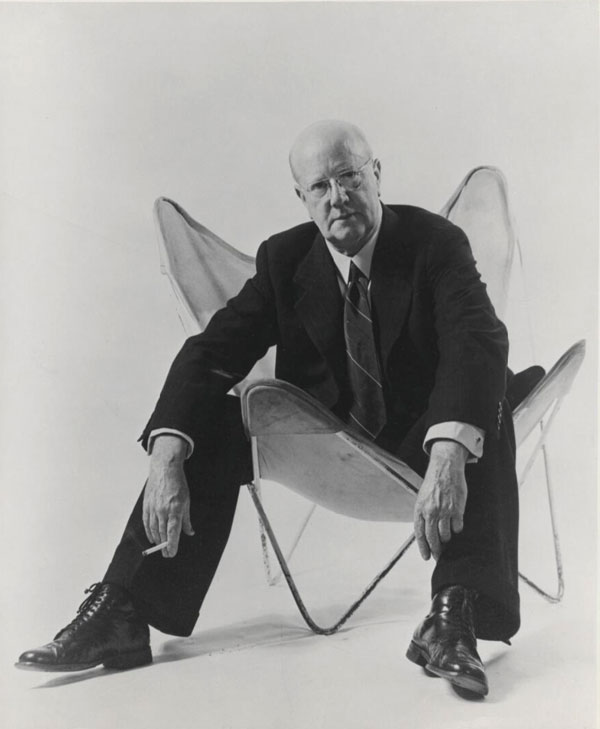

#1: Jack Cato by Athol Shmith 1955

INTRODUCTION

Jack Cato (1889-1971) was a photographer who did more than take photographs: he also wrote about himself and about other photographers. Until 1946 he was active in commercial photography in which field he established a considerable reputation as a portraitist. But his work, which has an intrinsic artistic quality, has still to be recognized aesthetically. In 1946 Cato sold his studio in Collins Street, Melbourne, and effectively retired from commercial photography, completing his unfinished orders from his home in Elwood.1

During the mid-1940's Cato began writing in earnest; his output was prolific. He published three books: 'I Can Take It' (1947) is an autobiographical work; 'Melbourne’ (1949) is a pictorial-documentary view of the city; and 'The Story of The Camera in Australia' (1955) renders an account of Australian photographers up to the 1950's.

He wrote extensively in a variety of magazines and journals, mostly but not always on photography, and mostly but not always in photographic forums.2

Between i960 and 1963 he was the photography columnist for 'The Age' newspaper in Melbourne. A considerable amount of Cato's work is unpublished in fifty-three manuscripts: these comprise autobiographical, semi-fictional and fictional material, and letters to and from his friends. (He kept carbon copies of his letters.)

Very little has been written about Jack Cato by any-one other than himself. An obituary (1971)3 and a short profile piece (1979)4 appear to be all that has been published to date. The public image of Cato is largely based on his autobiography 'I Can Take It’.

It seems reasonable to assume that autobiographical works present the picture that the author wanted to project to the world: sometimes the picture projected coincides with the person's self-image. Cato's unpublished writing suggests that his self-portrayal in 'I Can Take It' does not faithfully mirror how he really saw himself.

During 1949 and early 1950 Cato wrote a two volume work entitled 'Paul's Studio’5. Although it was favourably reviewed by Vance and Nellie Palmer6, Cato decided not to publish it for personal reasons.7 He wrote that

'Paul's Studio' is a work of fiction a composite story made up from the life of many studios, as Paul is made from many men I have known. I wrote into it a lot of romance – of love legal and love illicit.... But I've refrained,(from publishing it).8I felt certain that the public would swear that it was my own private story, and when I thought of my fine six grandsons being burdened with such a wicked, bawdy scoundrel of a grandfather, I decided to leave it to posterity.9

While Paul's adventures were fictional, Cato's son, John Cato, believes that in many aspects Paul's character and personality are substantially similar to his father's.

It is from an examination of all of Cato's work, written and photographic, published and unpublished that the private picture of Jack Cato emerges.

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Jack Cato was born in April 1889, the eldest of four sons, he was christened John.10 A fourth generation Tasmanian, Cato was proud of his familial origins and intensely interested in learning all he could about his forebears.11 A brief look at his immediate ancestors suffices.

Judging by their exploits the Cato's were a venturesome lot. From his great grandfather Joseph Cato, who in 1832 left his native Buckinghamshire for Tasmania12 (then called Van Diemen's Land), through to Cato himself, a strong pioneering spirit is evident.

Joseph Cato went on to prosper as a horticulturist and an orchadist, achieving success with experiments in hybridisation.

Cato's grandfather, Samuel Cato, progressed to become a chief executive of the Tasmanian Steam Navigation Co.13 formed when steam was just beginning to replace the sail.

Albert Cato, Jack's father, as a teacher was enticed to New Zealand by the offer of a higher salary. Later, back in Tasmania, he became an orchardist, leaving Hobart to take up land at Trevallyn "on the banks of the Tamar River near Launceston" where their "property was the last outpost before the virgin bush began.14

There is no mention of Cato's maternal family in any of his writings .

additional notes on the family:

1832: Joseph Cato (1792–1870) arrived Van Dieman’s Land 1832

Two sons

Joseph (1821-1884) married Fanny Hickman – daughter Emily marries John Watt Beattie (1859–1930)

Samuel (1831–1891) Married Harriet Hickman (sister of Fanny) – son Albert (1862-1930) (Albert close friendship with John Watt Beattie)

Albert’s son John (Jack) Cato 1889–1971

EDUCATION

Schools were too far away from the orchard, so Cato and his brothers were educated at home by their parents.

It must have been during this period when he studied Shelley and Keats and Tennyson and Shakespeare and the great masters of literature15 that he developed his lifelong passion for reading.

Later in life, Cato's taste in literature was almost exclusively for photographic and autobiographical works. His son John Cato remembers his father borrowing three or four autobiographies from the library each week.

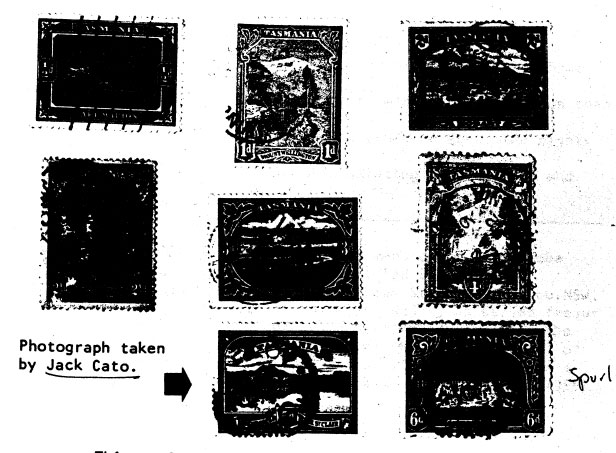

Cato's introduction to photography came in 1896, the same year that Henry Parkes died. It occurred when his cousin John Watt Beattie visited Launceston on a photographic excursion for a stamp series on Tasmanian landscapes which he had been commissioned to do.

Beattie, the son of an Aberdonian portrait photographer, emigrated to Tasmania in 1878 when he was 19 years of age. He began working commercially in photography in 1882, and by 1891 had his own studio which he expanded to include exhibition rooms for portraits and landscapes, a library and a museum; the last became an Art Gallery.

By the time Beattie died, he had acquired a considerable reputation in Tasmania for the beauty of his landscapes; he was also well known for his deep interest in the Island's lore and his magnificent art collections.16

In his recollections Cato recaptures his youthful admiration for his cousin. "To me Cousin John lived the finest life of any man alive - a traveller in unknown places a maker of beautiful and strange pictures by a magic process, making a livelihood on the mountaintops.17

His admiration did not diminish with maturity and experience as this tribute shows; "My cousin, John Watt Beattie, was a famous photographer - in my opinion, the finest landscape photographer of his age..."18

It was when Beattie was photographing landscapes for the stamp series that Cato, aged seven, took his first photograph: "Often we slept out on a mountaintop19 to get the first long shadows caused by the rising sun that gave modelling and relief to the landscape.

By the time we reached Lake St.Clair I knew a good deal about working those old cameras, so John me set up the camera, focus, and expose the picture of Lake St. Clair. This was one selected for the stamps. Thus my first 20 photograph became famous.20

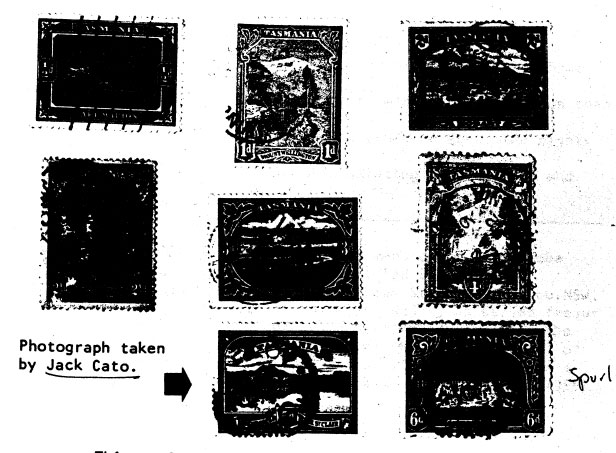

#2: the above composite to be replaced if better quality is identified

This series of stamps, illustrated above, was printed In recess by De La Rue Co. in London and was finally released for sale in December 1899.21 This was the first time that photographs were used as the basis for a stamp series anywhere in the world.22

The photograph that marked Cato's life-long interest in photography is reproduced on the 5d. stamp entitled 'Mount Gould Lake St. Clair’.

Extra note: Jack Cato's owned a major collection, and once owned the finest KGV 1d red piece - the mint block 6 of the Rusted Cliches and all adjoining flaws.

(edit: Exact photo not located. Mt Gould - no roads within 20 miles. The last could be one by Spurling)

Given this start in photo and his great admiration for Beattie, it is perhaps surprising that Cato did not show much interest in landscapes as a subject for his photography. It may not be altogether unreasonable to suggest that Cato's interest in portraiture came from his fascination with strong colourful personalities - such as his great grandfather and John Watt Beattie.

In 1898 when he was nine years old Cato came under the tutelage of two specialist teachers. By this time his interest in photography and art was evident, and his parents must have decided that he was talented enough to warrant more tuition than they could give.

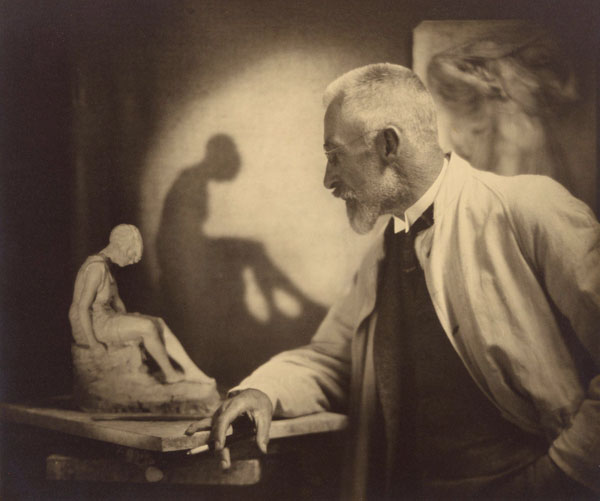

For the next three years he spent two nights per week, from 7 to 9 pm studying painting and drawing and being trained in artistic observation at Lucien Dechaineaux’ private art school in Launceston.23

(edit: Launceston Technical School not private as it does not start till 1907)

It was a significant experience for Cato, and later in life he recalled that Dechaineaux “led me to the culture of Europe, to literature, to read the lives of the artists, the poets and the musicians, and to hundreds of works on the fine arts.

(edit: 1912, Dechaineaux member of the Northern Tasman Camera Club)

"Every day with him was an inspiration. He was not an easy taskmaster; nothing second-rate was good enough, and I have to thank him for my life long contempt for it. His credo was 'Always aim at the highest.”24

Another two nights a week were taken up with learning about chemistry and metallurgy from John Milien, chief assayer for the Mt. Bischoff Tin Mining Co.25 Cato credits the comprehensive grounding in chemistry which he received at this time for his ability to produce different photographic effects which later accounted for his success in Hobart and London.26

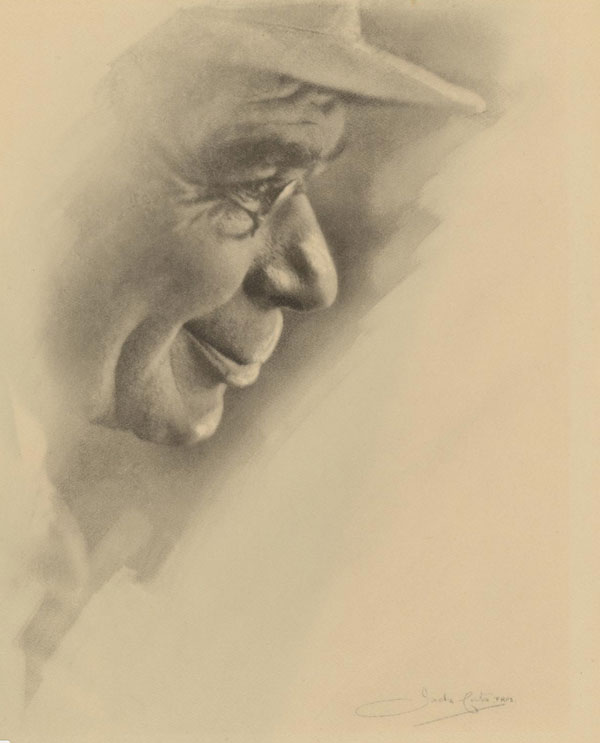

#3: Cato took the above portrait of his former art master Lucien

APPRENTICESHIP

As a twelve-year-old boy, Cato spent his Wednesday afternoons photographing the children of well-to-do Launceston families, making a profit of thirty shillings a week by the enterprise. His "darkroom was a cupboard under the stairs in our city home. My finishing room was anywhere my indulgent parents made space for me. The printing was done out of doors on printing out paper."27

Towards the end of 1901, Cato was apprenticed to Percy White law, a Launceston portrait photographer.28 Cato records that his mother “took a portfolio of my drawings and water-colour portraits to show" Percy Whitelaw. And the "Next day a five year's apprenticeship was arranged for me, and paid for." 29

As Cato makes no mention of them, it seems that his photographic portraits may not have been included in the portfolio shown to Whitelaw.

Cato's notes for this period suggest that Whitelaw must have been a remarkable man because, contrary to the established commercial practice of the day, he shared his knowledge and skills with his staff.30 "At five o’clock every afternoon in summer, when the light was still good, Whitelaw had all the staff, male and female, up in the studio teaching them the techniques of taking a good portrait".31

Whitelaw's approach to portraiture appears to have been strongly influenced by the portrait photographer H. Walter Barnett (1862-1934). Cato writes that "On Percy's annual, early trips to Sydney, before my time with him, and before Walter Barnett had gone to London to become Court photographer to King Edward VII, and later King George V, Percy always called on Barnett, and all that he tried to teach us was, "The way Barnett did it."32

H. Walter Barnett owned and managed the FaIk Studio in Sydney. As early as 1885 he had departed from the convention, established during the mid-1850's of retouching the negative.33

Cato claims, incorrectly, that Barnett "was the first man to deliberately photograph the course, deep toned texture of the skin; to show the bone structure of the skull and to portray the sculpturesque modelling of the human head".34 It would be more correct to say that Barnett led the revival of realism in photographic portraiture.35

(edit/note: ?? See page 11 of thesis)

Cato wrote that Whitelaw "gave the people of Tasmania the same standard of portraiture they would have obtained in Mayfair, London, for ten times the fee."36

This suggests that Barnett, while at the Falk Studio, Sydney, may have already developed the unorthodox approach to portraiture seen in his London (1899-1916) work. The practice in commercial photography is to adopt a standard lighting and compositional formula to achieve a distinctive style which (so it is believed) attracts a clientele.37

Barnett's London photographs, and Cato's Hobart (1920-1927) and Melbourne (1927-1946) photographs are distinctive because they do not conform to this practice.

During his apprenticeship with Percy Whitelaw, Cato became "his assistant operator - standing beside him as he took every sitter, changing the plates, moving the backgrounds, handling the screen and blinds that controlled the lighting and doing all the chores necessary to the taking of a portrait."38

This account of his time with Whitelaw differs from that given in 'I Can Take It’ where Cato states that Whitelaw only taught him retouching, and credits John Andrew, Whitelaw's competitor, for his "first lessons in operating.39

In 1904 Cato's apprenticeship with Percy Whitelaw was terminated on medical advice. In his doctor's opinion, Cato's eyes were "overworked" and he had "the option of stopping work or going blind".

As Cato was determined to continue his photography, the doctor advised work in the darkroom "where the dull red safe-light would enable his eyes to recuperate."40

Cato was only out of work for one week before he started work in the Van Dyck Studio darkroom, at thirty shillings per week. The Studio was owned by John Andrew, previously the chief artist of Talma Studio in Melbourne. At this time Cato was fifteen years of age.

Andrew had imported an arc lamp from America so that portraits could be taken at night. Andrew's health was poor and because of this he employed Cato to take portraits in the evenings, when the studio was open between 7 and 9pm. The business prospered, yielding a profit of twelve pounds per week, and Cato's weekly earnings were increased by twelve shillings and sixpence.

But Cato did not remain satisfied for long, and in 1906, at the age of seventeen, he decided to launch out on his own. Hobart, with a population twice the size of Launceston's, did not have a first-rate portrait studio and so offered more scope than Launceston where both Percy Whitelaw and John Andrew were well regarded.41

HOBART (1906-1908)

Cato leased a portrait studio in his cousin John Watt Beattie's premises in Hobart42, and began operating his own business which he ran successfully for two years. During this time he boarded with Captain and Mrs. Johnson, of Battery Point, and through them was introduced to Hobart society.43 Although Cato does not record it, this social connection probably contributed to the success of his business.

In 1908 Cato applied to join Douglas Mawson's Antarctic expedition as official photographer. By this time, although he was only nineteen years of age, he possessed seven years of experience in photography, and later wrote: "All of those who saw my prints assured me that I would be selected.44

But it was the young Sydney photographer, Frank Hurley (1890-1962), who was selected, and Cato later wrote: "The day after I heard that Hurley had got the Mawson appointment, I went to a shipping co. and booked my passage to Naples."45

The Inference here, that Cato was greatly disappointed at his failure to get the job, Is supported by evidence suggesting that many years later - when researching 'The Story of the Camera In Australia' Cato commented in a letter to Frank Hurley how much he envied his magnificent career.46

LONDON (1909-1914)

After touring Europe for twelve months Cato made his way to London with the Intention of seeking experience in a London studio. While in Paris he had worked in a photographic studio but resigned after two weeks because there was nothing for him to learn there.47

By 1909, when Cato arrived in London, H. Walter Barnett, in London since 1899, had acquired an international reputation as a first-class portrait photographer. Because they were fellow countrymen and because, thanks to his Launceston apprenticeship with Percy Whitelaw, he was versed in the manner of Barnett, Cato hoped that Barnett would give him a job.

Barnett was impressed with Cato's portfolio and hired him as his assistant operator, it happened to be that the job was vacant as the previous assistant operator had left a fortnight before.

Cato claims that he would have worked gratis for Barnett but "asked for four pounds a week. He scoffed at such insolence from a beardless youth then said, 'In the building opposite I have a furnished flat which I do not now use. (His mistress had left him) I'll pay you three pounds and let you have the flat free.48

As he remained with Barnett for only nine months, Cato may have been disappointed in his expectations of what more he could learn from the man who had been such a significant influence on Percy Whitelaw. (Edit/note: I seemed that Cato did not like Barnett)

While Barnett was away on his monthly convalescent trips, instead of cancelling his engagements he allowed Cato to photograph the clients, scrutinising all the glass plate negatives on his return. It Is possible that Cato's work was, as well as being comparable in style,of a comparable standard to that of the Master, as the following passage illustrates: "all negatives he did not tike, he smashed on the edge of the table, covering the floor with shattered glass while I stood there hating his guts. A few of my sitters were written to and asked to come again, but most of my work got by.49

After leaving Barnett's studio, Cato placed an advertisement in the 'Situations Wanted' column of the British Journal of Photography. This resulted in the offer of premises to start a portrait studio in Cardiff. Although he was free to work as he wished, Cato lasted nine months before the "perpetual drizzle" of Wales sent him back to London.50

Between 1912 and 1914 Cato worked with Claude Harris in London, paying the rent for the Regent St. studio in return for the use of the latter's equipment.51

Both men specialised in photographing the stars and personalities of the theatre, the dance, and the opera. Harris had been an actor, but when Cato met him he was rapidly gaining a reputation for his portraits of thespians.52 Harris photographed in a classical style, while Cato specialised in an apparently informal but highly controlled style.53

Cato's photography during this period cost him dearly: constantly working in draughty conditions backstage, he contracted T.B. and had to leave England.54

Although Harris does not appear to have had a significant Influence on Cato's photography, Cato wrote to him frequently after he left England, which suggests that he valued his friendship.

#4: Inscription on mount: 'Anna Pavlova, taken at her home in Golders Green. 1912'

#5: Untitled. This picture Is an example of Cato's backstage work in London

between 1912–1914 ,the period of his association with Claude Harris.

(edit/note page: Correction, photographed during the production of “Aida” Melbourne 1929)

AFRICA (1914–1920)

Taking his doctor's advice, Cato left England for a warmer climate; before his departure he sold the negatives of his London output to a "press–illustration bureau in Paternoster Row, London".55 In 1914 he arrived in Grahamstown, Africa, equipped with boxes of glass plate negatives which had been sensitised for work in the tropics.56

In 'I Can Take It’ Cato's reasons for choosing to go to Africa other than for its climate are treated glibly, consistent with the glamorous image he tries to portray in that work. Nor are they clearly stated in his manuscripts on his African experience so his true motives in going must be inferred.

Two prominent factors merge: his pursuit of becoming a fellow of the Royal Photographic Society is one: the other is his sense of adventure the same motivating force that earlier had led him to apply for Mawson's Antarctic expedition.

On his arrival in Grahamstown, Cato was employed by a Professor Corey of Rhodes University to illustrate thirteen volumes on the native wars. Cato described the work as a documentation of “the bloody history of the Kaffirs’ struggle to push the white man into the sea.”57

Cato spent six years working on this project and ironically, because he had left England for health reasons, intermittently recovering from bouts of local diseases.

Cato sent 120 photographs of his African studies to the Royal Photographic Society58 in London and these, together with a treatise, won him his fellowship on the 7th May, 1917. Aged twenty eight years, Cato was, at that time, the youngest member ever to receive a fellowship.59

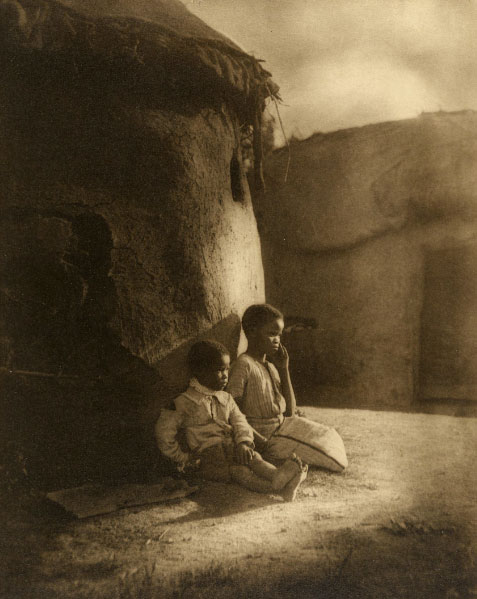

#6: Untitled. Africa (l914-1920)

#7: Untitled. Africa (1914-1920)

In 1920, at the age of thirty one, Cato's health once again prompted him to move. Still recuperating, he sailed for Hobart, taking with him 1,500 glass plate negatives of his African work. Despite their solid packing, most of these negatives were broken on arrival in Australia. All that remained of Cato's African photographs were a few prints.60

#8: Picaninnes. Africa (l914-1920)

This work was exhibited in the London Salon of Photography

and was also reproducedin 'Photograms of the Year’ 1916.61

CONSOLIDATION: Hobart (1920-1927)

After a few months convalescence, Cato borrowed a hundred pounds from his father, Albert Cato,62 and opened a studio in Hobart. Most of the money went on the Interior decoration: "The floor of the studio was midnight blue, furniture was black polished wood. All the leather was bright blue. All drapes, cushions, curtains and covers were Chinese mandarin.63

The intention was to make clients feel at ease, rather like guests in a comfortable home, except that the furniture - imitation Jacobean - was for sale. Whether it was the decor or the furniture, the studio certainly attracted custom and within twelve months Cato was able to repay the money he had borrowed. Cato's inspiration for his studio design came from the Paris studio in which he had worked for a brief period early in 1909.

Another noteworthy feature of these Hobart days is Cato's use of the Initials F.R.P.S. after his name in the studio insignia.

In 1923 Cato married Mary Boote Peare.64 Their two children, Paula and John, were born before the family moved to Melbourne in 1927.

#9: Untitled. Hobart (1920-1927)

The three photographs below are of Cato's wife Mary, and were taken on their honeymoon.65 The original works are bromide were taken on their honeymoon. prints and are handcoloured.

The three images are taken from a photocopy - we hope to replace them one day soon

|

|

|

| #10: Mary. Hobart (1923) |

#11: Mary, Hobart (1923) |

#12: Mary, Hobart (1923) |

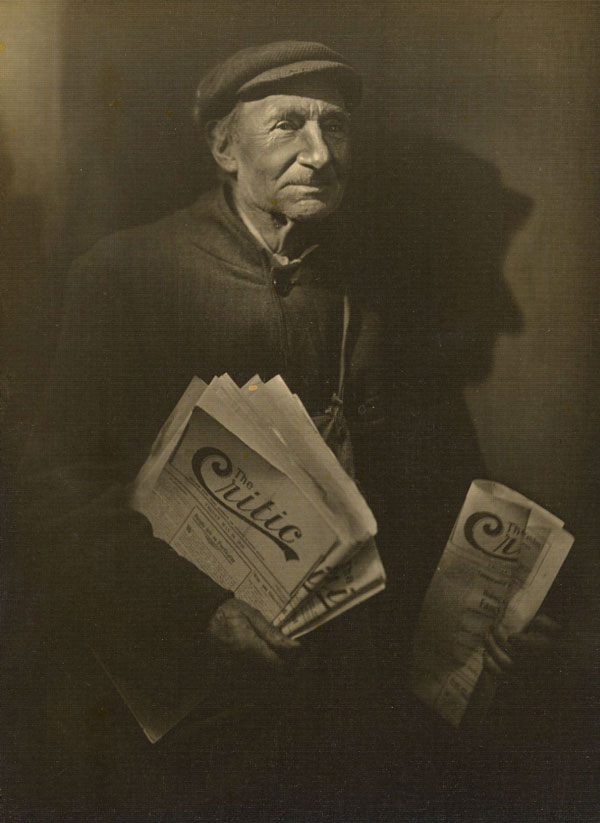

Cato regularly changed the display of prints in his studio window.64 The final display before he went to Melbourne was of Hobart's "odd characters" and was well received: "Everyone knew the subjects, but that they were picturesque and capable of being made into salon pictures seemed to amaze them.67 Three of these pictures are reproduced below.

#13: Nuggett, Hobart (1924)

#14: The Newspaper Seller Hobart (1924)

#15: 'Snorky' Hobart (1924)

MELBOURNE (l927-1946)

It was the advancing Depression which had already had an effect on his Hobart business that prompted Cato to leave Tasmania. But it was Dame Nellie Melba, who had befriended Cato when he was working with Claude Harris in London, who persuaded him to go to Melbourne where she lived.68 This was only four years before Melba died at the age of seventy.

With Melba's patronage and his impressive background in photography, Cato quickly established himself as the leading Society photographer in Melbourne,69 a position he was to dominate until his retirement from the commercial scene in 1946.

Cato was thirty-eight years old and had twenty-six years’ experience in photography behind him when he moved to Melbourne. All that he had gained in those twenty six years - from his early days with Percy Whitelaw, from his years overseas, from his Hobart studio -now came together and was manifest in his Melbourne work.

While patronage and commercial flair were responsible for his initial success, it was his consistently high standard of work coupled with his versatility of style that maintained his reputation.

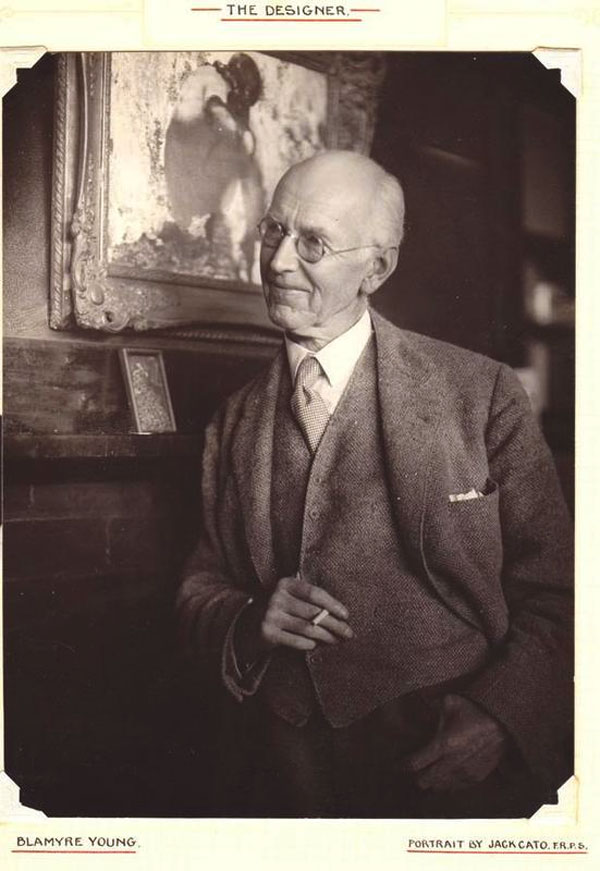

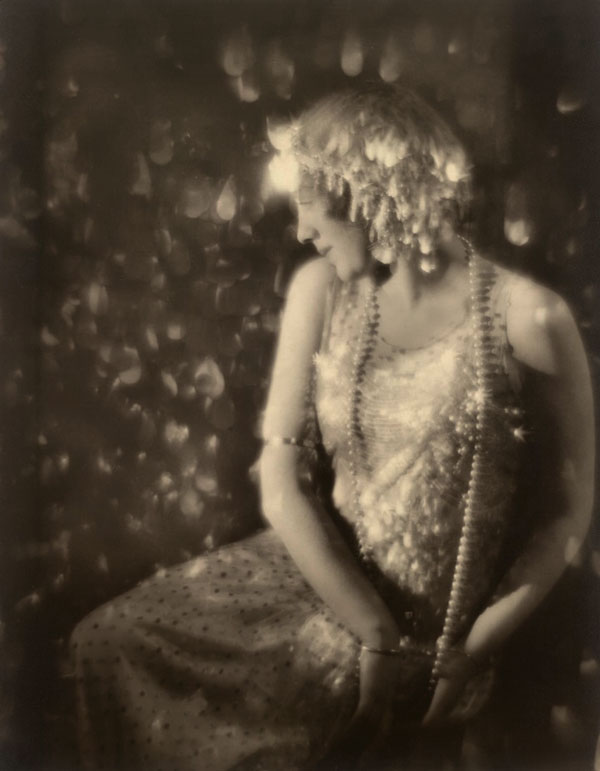

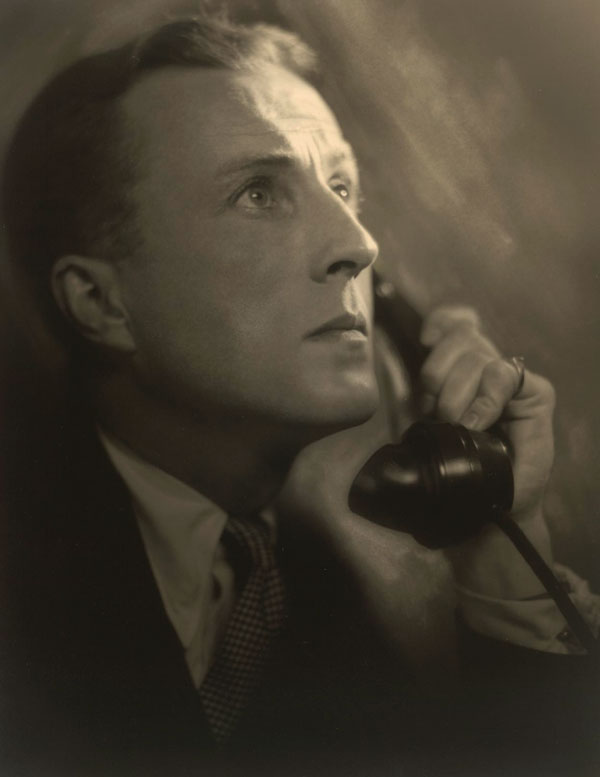

The portraits reproduced below illustrate the variety of styles in Cato's work. All are untitled and undated but two factors Indicate that they were photographed during 1927-1946.

Firstly, they do not bear the insignia which characterises his Hobart studio portraits. Secondly, all are photographed in a distinctly 1930's and 1940's idiom.

During this period Cato's earlier interest (evident in his London period with Claude Harris) in theatrical photography was revived. A precipitating factor may have been his association with Dame Nellie Melba and her circle. Cato often used stage technics high contrast lighting and exaggerated poses to achieve a dramatic effect.

#16:

#17:

#18:

#19:

#20:

#21:

#22:

#23:

#24:

#25:

#26: Duchess of Leinster 1911

#27: Martinet 1930

#28:

#29:

#30: (an advertising photo)

#32: Melisande' Melbourne (1927-1946)

#33: Untitled (1927-1946)

#34: Stephanie Deste 1928

#35: ‘Lina Scavizzi’ as the Nun, In "Thais" Melbourne (1927-1946)

(This image enlarged from another source)

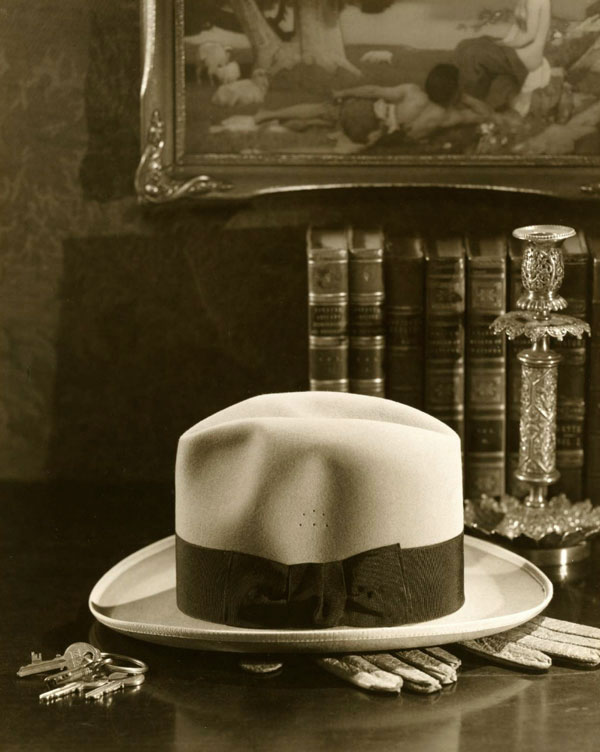

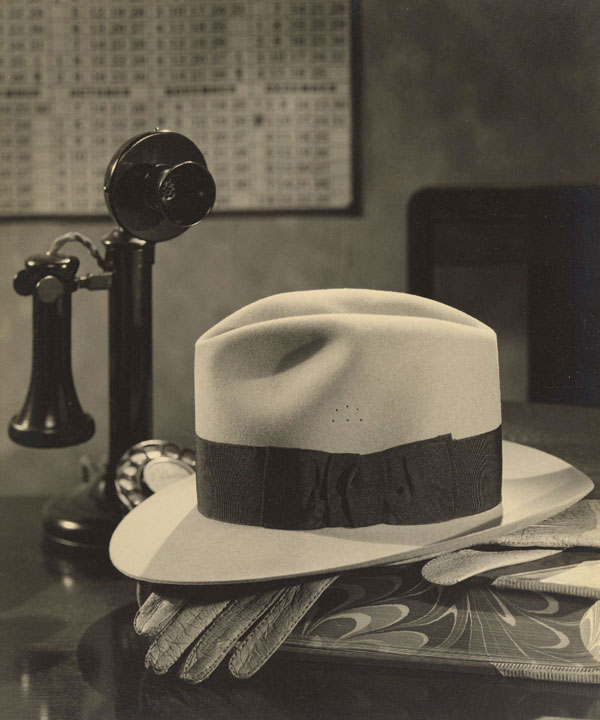

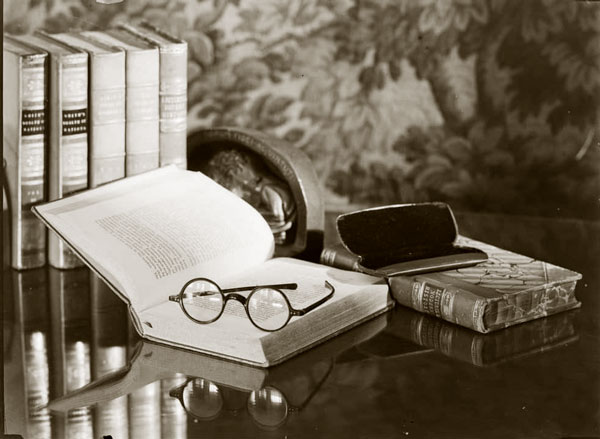

Also, during this period, Cato produced a number of photographs that could be described as 'implied portraits. The subject matter of these pictures strongly evoke a personality – the presence of the person is sensed even though not seen.

Three photographs illustrative of this work are reproduced below

#36: ‘Untitled’ First Prize Winner, International Salon, Melbourne, c.1930

yet to find a good copy of this?

#37: ‘Untitled’ Melbourne, ? c.1930

#38: ‘Untitled’ Melbourne, ? c.1930

#39: Spectacles Lying on an Open Book, circa1947

(this was not in the original thesis - but is a good compain to the above set)

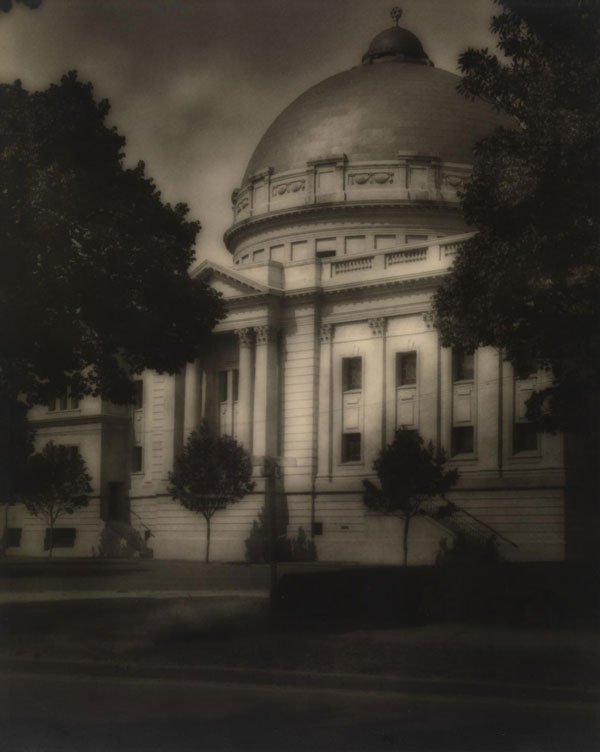

The following photographs were in an exhibition of a hundred photographs of Melbourne scenes which were to be the basis of a book - 'Melbourne' (1949). In manipulating photographs to beautify his subject matter he was using Pictorialist convention.

Later when reviewing his book, he articulated his pictorial aesthetic: "I wanted my book to be faithful record of the city. To be a mixture of the pictorial and the documentary, so that it would have enduring historical value, but with no intention of allowing the unsightly to dominate the scene.70

Arthur Calwell, then the Minister for Immigration, was obviously impressed because he "bought them for the Ministry of Immigration for five hundred pounds and sent them to tour the USA and Great Britain and for twelve years they were exhibited at Australia House, London, twice a year.71

#40: The Toorak Road Synagogue Melbourne 1940

#41: Gothic, Collins Street, Melbourne

#42: Mountain Lodge

#43: A Toorak house

Cato was fifty-seven when he retired from commercial photography in 1946. The frustrations of the war years were a major factor in his decision to sell his studio. The exigencies of the war had resulted in the imposition of a quota system on the distribution of photographic materials; commercial photographers were able to obtain only twenty five per cent of their usual requirements.

Cato adapted to this cutback by reducing his workload and by using smaller negatives - thus sacrificing quality. Staff were hard to get and no sooner was an assistant or a darkroom operator trained than he was enlisted into the services or was lured away by a competitor.72

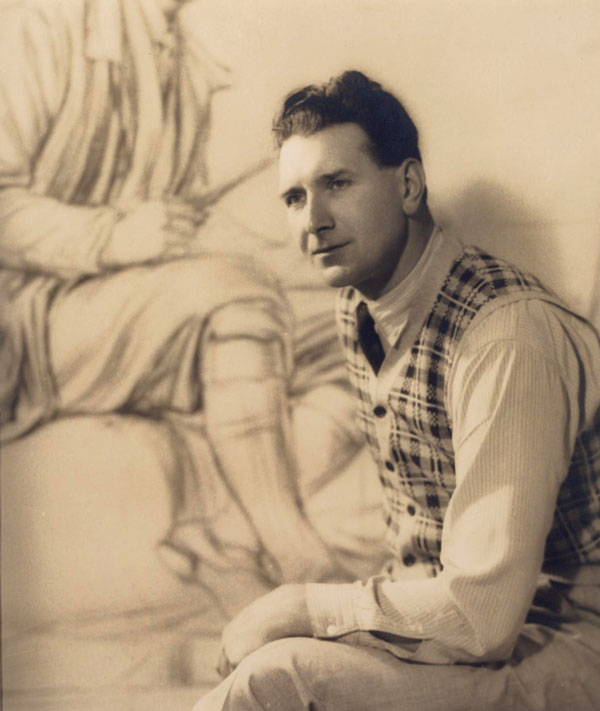

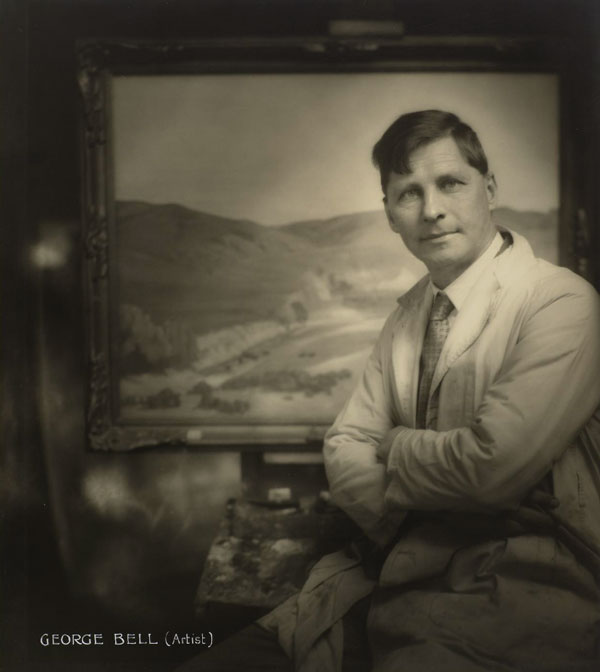

The following photographs are from a series of portraits of Australian artists, and are probably the only serious photographs Cato took after he withdrew from commercial photography.

Cato's use of the artist Len Reynolds' studio73 indicates that they were photographed after Cato had sold his studio (l946); as some of them were reproduced in ‘Can Take It’, they could not have been photographed after 1947 when the book was published.

It was while taking these photographs that Cato became involved with the Savage Club, a popular forum with many of the artists he photographed. He was nominated for membership of the Club by the artist Harold Herbert and the nomination was seconded by the artist Napier Waller.74 Later on, in October 1949 Cato was appointed Club Chronicler to the Melbourne Savage Club.75

#44: Napier Wallace, artist, Melbourne 1932

#45: George Bell, artist, Melbourne 1930s

ANOTHER MEDIUM (1946 - 1971)

In 1946 Cato concentrated his energies into writing ‘I Can Take It’ in fulfilment of a pledge made with his friends at the Savage Club one evening which ended in “pledging ourselves to prodduce some work of art, outside our ordinary medium, in a year's time".76

Twelve months later 'I Can Take It' was completed in manuscript form and was published late in 1947. As Cato wrote in December 1947 that "it is now over two years since aII of this took place.77 We may infer that the Savage club commitment was made late in 1945 or early in 1946.

That Cato went on to publish his manuscript indicates that he took the project far more seriously than his confreres wo produced such items as 'The Moonlight Sonata' – a character reading from Shakespeare -'Droll Stories' translated from the French. 78

The book was a commercial success and a second edition was printed in 1949. This result must have been gratifying to Cato who was entranced by the notion that a "sincere craftsman" should be able to work successfully with any medium.79 Cato was a well-known Melbourne personality and this, together with 'racy' style of writing - popular in the 1940's - probably accounts for the book having sold well. Its 'local interest' probably also accounts for Kodak having rejected Cato's offer of the book for publication overseas.80

The next book Cato published was 'Melbourne'(1949) this work should really be seen as an extension of his photographic work before he retired.81 The work is a pictorial documentary and is photographic in intent.

Also, in 1949 Cato was asked to "write ten thousand words on the History of Photography in Australia" for the second edition of the Australian Encyclopaedia.82 This seemingly simple request resulted in Cato embarking on a major project, when, on consulting the filing system at the public library, he found that "there was nothing at all written on the subject.”

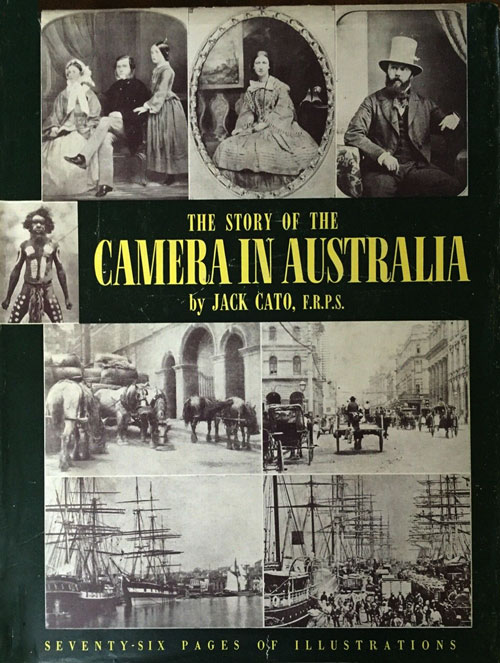

#46: The Story of the Camera in Australia 1955

‘The Story of the Camera in Australia’ published in 1955 is the outcome of Cato's attempt to remedy the situation..83 The book is a readable account of early Australian photographers but should not be regarded, as it has become to be, as a definitive history of Australian photography.

Cato's research methods for the book suggest that he was planning to focus on the technical, developments in photography and how these were applied by the photographers.84

But the outcome suggests that he became increasingly Interested in the personalities of the photographers and' less Interested in the processes. Thus 'The Story of the Camera in Australia' is a historical narrative rather than an academic work.

Cato clearly saw the work as a narrative for he wrote: "I keep before myself all the time this one definite fact that the title of my book is "The Story of the Camera in Australia.85

Cato accumulated a vast amount of information86 to supplement his already extensive knowledge - gained from forty-five years of experience - of photography and photographers. But he must have been aware of his lack of expertise in academic ways of writing and chose to model his work on William Moore's work.87

Despite the years of effort that went into the book, it did not sell many copies88 until 1977 when, because of the growing interest in Australian photography, a second edition was published by the Institute of Australian Photography.

#47: The Story of the Camera in Australia 1977

Between 1960 and 1963 Cato intermittently wrote for the 'Age', Melbourne. Most of his articles were about his own experiences or were anecdotes drawn from the material he had accumulated while researching for 'The Story of the Camera in Australia' - few, if any, were about contemporary photography.

During the last years of his life Jack Cato,was afflicted with glaucoma, suffered rapidly failing eyesight. In 1970, Mary his wife, died; from then on he was totally alone until his death in 1971 at the age of eighty two.

CONCLUSION

Cato, whether taking photographs or writing books, was a portraitist: his bias in both media is clearly towards presenting his subject in a flattering light. But his achievements with the camera are significantly better although less -well known than his books, in particular 'The Story of the Camera in Australia'.

However the grounds for comparison are hardly equal given that Cato spent forty five years perfecting his photography and only began writing late in life. Despite this, Cato's writing and his photographs must be considered together as a single-body of work expressing his lifetime preoccupation - portraiture.

A striking feature of Cato's photographic portraits is that they all differ in composition and lighting, giving the impression that some special quality or attribute unique to the subject has been captured.

The quintessence is photographed regardless of who the subjects are - be they eccentrics, theatre personalities, socialites, artists, or weddings. That Cato was able to maintain his 'virtuoso’ style for at least twenty-six years - the period after his return to Australia - is remarkable indeed.

He is probably unique among his Australian contemporaries in eschewing the use of a standard lighting and compositional formula.

The fact that Cato stopped taking photographs in1946 should not be dismissed as mere boredom or disillusion with the medium. Two factors are significant in Cato's decision to retire from commercial photography.

Firstly, Cute was challenged by the idea that a "true craftsman" should be able to work in any medium. This was the motivating force that led him to write 'I Can Take It' and sustained him through the years of exhaustive research to write 'The Story of the Camera in Australia.'

The second factor could be said to have 'triggered’ his retirement. The perfectionist in Cato could not accept having to work with the inferior materials forced on him because of the war: his early conditioning from his years with Lucien Dechaineaux in Launceston was too strong to allow him to tolerate the mediocre in his work.

Cato's photographic vision is discernible in his writing. He treated his literary subjects in the same way as he photographed his sitters: instead of picture-portraits he produced word-portraits. And whether, he was photographing or siting, he romanticised his subject - including himself in ‘l Can Take It’.

There's a sample of Jack Cato's photographs online with several public collections in Australia

such as the National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), the State Library of Victoria, The National Gallery Victoria,

and the Monash Gallery of Art

online public collections

also see the link in the menu (top and bottom of page) for a sample of other photographs

Please make contact of you know of another that could be linked from here.

FOOTNOTES

- Information about Cato's retirement from commercial photography was given by his son John Cato.

- These are listed in the Bibliography.

- In 'ProfessionaI Photography in Australia' Sept./Oct.1971•

- Gael Newton, (ed. and with text).'Australian Pictorial Photography'. Art Gallery of NSW, 1979

- Jack Cato, 'Paul's Studio'. Unpublished manuscript. One copy in LaTrobe Library, Melbourne; a second copy is in the possession of his son John Cato.

- Letter from Vance Palmer to Jack Cato, dated 19/3/50. In LaTrobe Library, Melbourne.

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutorsr Vol.1, 1966. Unpublished manuscript in LaTrobe Library, Melbourne.

- Words in parenthesis are my own.

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors' Vol 1.

- Cato explains that "at the font they labelled me John, but as as that was the colloquial name for any Chinese coolie who worked our market gardens, I was nicknamed Jack in the hope that it might distinguish me".Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It', Georgian House, Melbourne, 2nd ed. 1949.

- He was frustrated in this because the family records were destroyed by his brother's (Ted) wife. Jack Cato, 'The Cato's'. Unpublished manuscript, undated, in the possession of his son John Cato. to show that Cato inherited their drive and determination.

- With him were his wife and seven children one of whom died on the voyage.

- Later it became the Union Steamship Company of Australia.

- Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It', pp.14-15

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors' Vol.1.

- Jack Cato, 'The Story of the Camera in Australia', Georgian House, Melbourne, 1955. pp.80-87

- Jack Cato, 'John Watt Beattie and My First Photograph'. Unpublished manuscript in the possession of his son John Cato. page 1

- Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It1, page 22

- (GN note – unlikely – too cold!)

- Jack Cato, 'John Watt Beattie and My First Photograph, page 2

- Jack Cato, 'Philately'. Unpublished manuscript in LaTrobe Library, Melbourne. Information verified in the '1980 Seven Seas Stamp Catalogue1, Seven Seas Stamp Co., Dubbo, NSW. Cato was a keen philatelist. Between 1929*^9 he served freguently as President or Vice-President of 3 stamp clubs: the Prahran Philatelic Society; the Royal Philatelic Society of Victoria and the Commonwealth Specialists' Society.(From a letter to Keast Burke, editor, Australian Photo Review. 1955)

- Jack Cato, ibid. c

- Lucien Dechaineaux emigrated from Belgium in 1882 and lived for a short while in Sydney before moving to Tasmania. In Launceston he founded a private art school that he ran between 1895-1907. In 1907 he founded and was appointed principal of the Hobart Technical College. In 1939 he moved to Sydney and was appointed lecturer in design at East Sydney Technical College. He moved back to Hobart shortly before his death in 1957. He was known as “The father of technical education in Tasmania.” (Alan McCullock, 'Encyclopaedia of Australian Art’, page 161

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors' Vol.1

- Between the years 1919-38 John Mi lien was a Federal Senator for Tasmania, representing the National Party.

- Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It', pp.28-29

- Jack Cato, 'On The Studios'. Unpublished manuscript in La Trobe Library, Melbourne. Undated.

- The flyleaf to the 2nd edition of 'The Story of the Camera in in Australia' (1977) is incorrect in stating that Cato was apprenticed to John Watt Beattie.

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons1 Vol.1. Unpublished manuscript in La Trobe Library, Melbourne.

- Most commercial photographers kept their process a closely guarded secret; each employee was taught only one aspect of the process. The object being to safeguard the oligopoly of the photographers.

- Jack Cato,'My Tutors' Vol.1

- bid.

- Retouching was used to remove all blemishes and skin texture from the subjects face. It was used mainly for male portraits, to cater for the demand for an 'idealised’ image.

- Jack Cato, 'What Made Barnett's Portraits Outstanding'. Unpublished manuscript in LaTrobe Library, Melbourne. Undated, page 2.

- Two significant photographers pre-dating Barnett's use of this technique were Gaspard Felix Tournachon (known as Nadar) (.1820- 1910) and Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879).

- Jack Cato, ‘The Story of the Camera in Australia', p.168

- Early studios were often called such names as 'Rembrandt' and Van Dyck, no doubt in order to evoke the style of the Masters.

- Jack Cato,'Sermons' Vol.1

- Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It', page 29. On this point, see also the section referenced by the indices 30 and 31 in the footnotes on page 10 above.

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors' Vol.1

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors1 Vol.1

- The premises had been vacant for five years. Beattie, a landscape photographer, had hired an English couple, Mr & Mrs Reynolds, to operate the portrait side of the business. But the couple committed suicide in the same year that they were hired and Beattie, perhaps daunted by this, never bothered to employ anyone else, (ibid)

- ibid, page 2

- Letter from Jack Cato to Claude Harris. Undated, In the poss ession of John Cato, Melbourne.

- ibid.

- ibid.In reply Hurley wrote; "Fancy you envying me! I am only an outdoor cameraman, you are an artist." (GN Note??? Page 15)

- Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It'. Cato got this job on the condition that he taught the owner's son English.

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors' Vol. 2

- Jack Cato, 'Number Twelve Hyde Park Corner'. Unpublished manuscript, LaTrobe Library, Melbourne. Underlining denotes my emphasis.

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons' Vol.2. The respondent was Charlie Whit-lock (Whitlock & Co. Wolverhampton, commercial photographer.)

- Letter to Claude Harris. Undated.

- Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It' page 79

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors' Vol.2

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons' Vol.2

- Jack Cato, 'My Tutors' Vol 1.

- These plates were especially prepared for him by Dr. Kenneth Mees of London University, later head of Kodak.

- Jack Cato, 'Jack Somers and My African War'. Unpublished manuscript. Undated. In LaTrobe Library, Melbourne.

- From my previous experience with it I know that the R.P.S. collection is mostly uncatalogued: a researcher would have to sift through hundreds of unlabelled boxes of photographs to find these.

- Jack Cato, 'Jack Somers and My African War'. Date fellowship received verified by F.R.P.S. certificate in the possession of John Cato.

- Jack Cato 'My Tutors' Vol.1. Prints in the possession of John Cato.

- Jack Cato, 'Jack Somers and my African War.

- while Cato was overseas his parents had moved from Launceston to Hobart, where they had a home in Sandy Bay.

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons' Vol.1

- Mary Boote Pierce was born in Northcote Victoria and, when very young, moved with her family to Kalgoorlie, WA, for 24 years before going to Hobart. (Jack Cato, 'The Girl of the Golden West' Unpublished manuscript, LaTrobe Library, Melbourne and John Cato.)

- Information given by John Cato.

- Jack Cato, ‘My Studios'- Unpublished manuscript, LaTrobe Library, Melbourne.

- Jack Cato 'I Can Take It', page 173.

- Jack Cato, 'I Can Take It' page 176

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons Vol. 1

- Jack Cato, The Face of the City. In the Australasian Photo Review, May 1949. page 301

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons' Vol. 1

- Information given by John Cato. Some of Cato's frustration at this time is expressed in the following poem which he wrote:

'Memo Mr Cato'

The King was in his bedroom

a'mending of his hose.

The Queen was in the laundry

a'washing of the clothes.

The maid was in the garden

eating bread and honey.

When along came a neighbour

and offered her more money.

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons' Vol. 2

- Jack Cato, 'Sermons ' Vol. 2

- The Chronicles record Cato's association with the Melbourne Savage Club and are held in restricted access in LaTrobe Library, Melbourne. The date of Cato's appointment as Club chronicler was obtained from a letter from the Savage Club; held in LaTrobe Library.

- Jack Cato, 'Story of I Can Take It', The Australasian Photo Review, December 1947. page 681

- loc.cit.

- loc.cit.

- op.cit. page 679 and also 'Paul's Studio'.

- Letter from Dr.K.Mees of Kodak, dated 7th December 1948. In LaTrobe Library, Melbourne.

- See also page 49.

- Jack Cato,'The Story of the Camera', The Australasian PhotoReview, page 690

- ibid

- The catalogued the information he collected under these headings: "cabinets; wet-plate landscapes; lantern slides; movies; aerial photography; first dry plate etc." Letter to Harold Cazneaux, dated 28th Feb.1951. In Mitchell Library, Sydney.

- Letter to Harold Cazneaux, dated 9th March,1951.Mitchell Library

- His sources were: "The National Gallery; The National Library' and its Historical Section; The Royal Historical Society; The Government Archives... the affiliated societies in the different States" and hundreds of informants which he had traced. (Letter to Harold Cazneaux, dated 28th Feb.1951)'

- He wrote: "I believe my book will eventually be as complete asWilliam Moore's 'The Story of Art in Australia' and perhaps much more colourful, because the painter stayed 'put' while the camera travelled the whole continent recording the manners and customs of the people and giving us a picture that makes our history more vital and real to us than any other period." (Letter to Harold Cazneaux,dated 5th Feb. 1951).

- The book could not sell at its jacket price of £6/6/- and was remaindered. (Information given by Georgian House, Publishers.)

Selected exhibitions

1923 Group Show of the Professional Photographers Association of Tasmania, Hobart.

1925 Solo Show of landscapes, The Bookshelf Gallery, Hobart.

1932 Solo Show, Athenaeum Gallery

1934 Group show Centenary International Exhibition of Professional Photography, Athenaeum Gallery, Melbourne. Awarded Silver Medal in Commercial section.

1936 Group Show Kodak AAsia Pty. Ltd. Gallery, Collins Street, Melbourne

1937 Group Show of early Kodachromes at Kodak Australasia Pty. Ltd., 45 Elizabeth St., Hobart.

1938 Queen Victoria Museum Art Gallery, Launceston

1995 Included posthumously with Athol Shmith, Harold Cazneaux, John Lee, Laurence Le Guay and Max Dupain in National Portrait Gallery curated exhibition High Society: Society Portraiture and Photographs

2002 Included in exhibition Just Married, Monash Gallery of Art, Wheelers Hill, 6 September-20 October 2002.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Published Work by Jack Cato

- A Letter from Jack Cato. Professional Photography in Australia. Sept/Oct 1956.

- An Apple Islander Debunks the Convict-Bushranger Legend. The Bulletin. 18th March I959. p.11

- Arthur Dickinson FRPS AIVP. Professional Photography in Australia. Oct. 1961. pp.6-7

- Composition and the Movies. Australasian Photo Review. 15th Aug. 1923. pp.393-395

- Cover Designs. Australasian Photo Review. Sept. 1952. pp.532-536

- Crime and the Camera. Professional Photography in Australia. Feb. 1958. pp.12-15

- Double Exposure. Professional Photography in Australia. June 1958. p.19

- Extend the Subject Matter. Australasian Photo Review. June 1953. pp.335-341'

- George Lionel Marchant 1882-1958: Our Most Colourful personality. Professional Photography in Australia. April 1958. pp.5-8

- I Can Take It: The Autobiography of a Photographer. Georgian House, Melbourne, 1947. 2nd ed.1949.

- I Can Take It. (Book Review). Australasian Photo Review. Dec. 1947. pp.679-682

- I Can Take It. (Book Review). Book News. Dec.1947. pp.301-305

- Interiors With a Kodak. Australasian Photo Review. Oct.1923. pp.497-498

- Is Everything in the Lens? Australasian Photo Review. May, 1922. pp.237-239

- Melbourne. Georgian House, Melbourne, 1949.

- No Questions Please. The Melbourne Walker. Vol.30, 1959. p.11

- Photography and Pharmacy: Part I, Feb.1957. pp.137-142 & Part II, April, 1957. pp.406-411 Australasian J. of Pharmacy.

- Photography and the Arts. The Educational Magazine.

- Vol.9, No.10, Nov. 1952. pp.451-452

- Pioneers and Wetplates. Walkabout. July, 1964.pp.29-33

- Port Arthur's Poignant Past. Walkabout. Dec. 1961.pp.52-54

- Portraiture and the Background. Australasian Photo

- Review. Part 1, Jan. 1924. pp.10-13 £ Part 11, March, 1924. pp.127-138

- The Australian Legend. The Bulletin. 11th Feb. 1959. pp.46-47

- The Camera in Australia. Photo News. Aug. 1954. pp.9&60

- The Cazneaux Story. Australasian Photo Review. Dec. 1952. pp.720-737

- The Cleaverest Camera Stunt I Ever Saw. Professional Photography in Australia. Aug. 1959- pp.8-9

- The Face of the City. Australasian Photo Review. May, 1949. pp.301-308

- The Human Comedy. Professional Photography In Australia. Oct. 1959. pp.8-10

- The Story of the Camera in Australia. Georgian House, Melbourne, 1955. 2nd ed. Institute of Australian Photography, 1977.

- The Story of the Camera in Australia. (Book Review). Professional Photography in Australia. Jan. 1956. PP.17-19

- Three Tributes For The Late Frank Hurley. Australian Popular Photography. March, 1962. pp.30-33&48

- Tribute to Monte Luke FRPS. Professional Photography in Australia. Dec. 1962. pp.6-7

- Vanity in our Photographs-What the Photographer Sees. Professional Photography in Australia. April, 1960. pp.8-10

- What Made Them Successful. Professional Photography in Australia. Aug. 1954. p.12

- Writing "The Story of the Camera". Australasian Photo Review. Nov. 1955. pp.690-692

- W. Jerome. A History of Photography. Percy Lund and Co. Bradford, U.K. 1888.

- McCulloch, Alan, Encyclopedia of Australian Art. Hutchinson of Australia. 1968.

- Tanre Con with assistance from Davies, Alan & Stanbury, Peter. The Mechanical Eye. The MacLeay Museum, Sydney.

- Horton, Mervyn. The Beginnings of Australian Cinema. Australian Film Institute. 1964.

- Ziegler, O.L. Australian Photography. No.!, 1947. No. 2, 1957.Ziegler Pub. Sydney.

Unpublished Works

- LaTrobe Library, Melbourne:

- Cato, Jack.

- A Few Kind Words. Vols. 1 & 2.

- Africa.

- African Studies.

- Bi11 Buckland. Vols. 1 - 5.

- Bill Walkley.

- G. G. Jobbings and Bogong-Jack and Professor Wood-Jones .

- Harold Herbert. Vols. 1 - 3.

- Hurley etc From The Books.

- Jack Cato To Staniforth Rickson.

- Jack Somers and My African War and War Letters to Eric Harding and to Ian Mair.

- Lectures.

- Melba and Opera. Vol. A.

- More about Louis Buvelot and Australian Movie Films.

- Murder Most Foul. Vols. 1 - k.

- My Studios.

- My Tutors. Vols. 1 & 2.

- Ned Kelly.

- Number Twelve Hyde Park Corner, Knightsbridge.

- One Man Shows. Vo1. 1 .

- On The Studios .

- Paul 's Studio. Vols. 1 S 2. Oct. 1951.

- Pharmacy and Chemistry.

- Philately .

- Professor Wood-Jones .

- Robert G. Menzies. Vols. 1 & 2.

- Sermons. Vols. 1 & 2.

- Sir Robert Menzies. Various manuscripts dated 1953 - 1964.

- Some True Romancings Including The Girl of the Golden West.

- South Africa.

- South Africa- A Digest of the History of South Africa, George Cato First Mayor of Durban.

- South Africana.

- Staniforth Ricketson to Jack Cato.

- The Australian Film Industry.

- The Very Reverend Roscoe Wilson.

- Writers

Other correspondence:

Correspondences Between Jack Cato and Nancy Cato. - Mitchell Library, Sydney:

Correspondence Between Jack Cato and Harold Cazneaux. - John Cato, Melbourne:

Cato Jack. John Watt Beattie and My First Photograph - The Cato's.

Correspondence Between Jack Cato and Claude Harris.

Letter to Dear Leo.

A

STORY of The

STORY: Correspondence

between Jack

Cato and Keast

Burke,

Gael Newton,

Photofile,

Autumn 1984

for more on Jack Cato - click here