IMPORANT NOTICE: photo-web does not sell or provide any information on Wesley's photos more than what is on this site

We do not hold the copyright; we cannot give permissions for any use of Wesley's photographs

About Wesley Stacey's estate and copyright matters

About Wesley

Born 1941 - died 9th Frebuary 2023

After studying drawing and design at East Sydney Technical College from 1960-62, Stacey worked as a graphic designer and photographer in Sydney and London from 1963-66.

In the late 1960s he worked as a magazine photographer based in Sydney; from 1969-75 he freelanced as a commercial photographer, and in the mid-seventies he travelled around Australia in a camper-van.

With David Moore and others, Stacey helped establish the Australian Centre for Photography in 1973-4.

He often used a Kodak Instamatic camera during the seventies, making series of informal images of his friends and recording his environment.

Since the early 1980s, he has employed a panoramic format to produce photographs which explore the symbolism of the natural environment and the sacred links of the Aborigines with the land.

His work was included in !Eureka! Artists from Australia at the Serpentine Gallery, London in 1982 and Australian Perspecta at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1983.

A retrospective of his work was held at the National Gallery of Australia in 1991.

In 1992 he was awarded one of the newly established Australia Council Creative Arts Fellowships.

His exhibition Signing the Land (1990, published in book form in 1993), juxtaposes images of inscriptions and graffiti photographed in Italy with recordings of Aboriginal and European markings on the Australian landscape to suggest a cultural commonality among peoples.

Wesley continued to travel the country, working from a base on the south coast of New South Wales. He died on the south coast in February 2023.

The above introduction based on the text for the catalogue

Australian Photographers of the Seventies

from the Collection of the National Gallery of Australia: Philip Morris Arts Grant

Artist Statement 1988

'Using the outer light, return to insight.' Lao Tse (China, 6th century BC)

Is photographing the landscape merely a vain attempt at souveniring something from the place?

Is it a familiarizing process, an act in comprehension of the environment?

Is it an act of superiority, trying to tame these wondrous surroundings? Could it be that we like to arrest life with photography, and in capturing a bit of the cosmos get temporary satisfaction of power over decay.

What about landscape as purely an arrangement of forms to delight the eye, the materials of artistry, for the artist's aesthetic imagination?

Or more importantly is that familiarizing process the beginnings of a deeper understanding of where our place is in the relation of things? A coming to terms with the place? Even a celebration? Perhaps the spirit of the land is calling one to respond.

I study the subject of landscape picture making, the traditions, the visions, the heroes - and continue to have a go at making some for myself, oft wondering whence comes the drive to keep at it - and the function landscape pictures have in our culture.

I allow myself to be drawn to landscapes and sometimes I feel like Luke Skywalker, with an accompanying life-support vehicle, on the Desert Barrier Range, remote.

I love being out in it, immersed, involved with photographic possibilities, with my individual point of view, personal but shareable - essentially interactive with others.

The interacting elements of this place - me here - this time could be made explicit in some photography here. Cloud shadows are racing across grassy hillsides. The light is looking great.

Here is a subject I now have a fix on, or it has a fix on me, and the light is changing quickly. It might not be so good in a minute. This is a scene the landscape photographer must rise to. It will add to the landscape genre.

What this picture probably won't show is the urgency and compulsion I feel now this potential photograph has become important to me. How quickly can I get the camera in position?

The ancient wisdom comes to mind: 'He who acts defeats his own purpose'.

But still calculating the permutations and the circumstances I'm on the run, with the elements in a state of flux.

Self-esteem demanding: For the picture! For the glory! (Ego-computer records motive: vanity/whim).

I'm going for it. This is photography. Astride the wire avoiding the barbs.

Where exactly to place the camera?

Forward back check framing

secure tripod up down calm down

be here filter on? Calm speediness.

Speed aperture don't forget focus!

This place me here this time.

Light's gone flow with the go.

Light's come good check framing

press shutter release no click!

Keep calm, logic will solve this.

Cock the lens - Ferglewit!

Light's good - Fire one!

Wind on replace ...

The lens cap is on!

Did I replace it automatically without thinking? I think I had it in my hand for the exposure.

Light's still there. Try another one? No. That's it. Too bad if its a blank frame.

I've turned my back on it and now what's important is to be here, responses open, and perhaps something will come of the experience.

Buffeting wind, stubble and rocky ground. Light rain prickling furrowed brow.

Tripod and camera askance over my shoulder.

Maybe I could enjoy the place more without trying to take a photograph. Although doing this sort of thing gives me continuity and some sense of purpose. In some ways it satisfies.

Especially if an exciting picture comes of it. Can't wait to process the film and see that image.

That's something to look forward to.

The most exciting pictures are still in the camera.

Tantalizing.

Wesley Stacey

Autumn 1988

Monash Galley of Art Exhibition

2017 Exhibition at Monash Gallery of Art: Wesley Stacey - The Wild Thing

Click here

Gael Newton essay 1991

exhibition at Gallery 4A

National Gallery of Australia

23 February – 12 May 1991

|

|

|

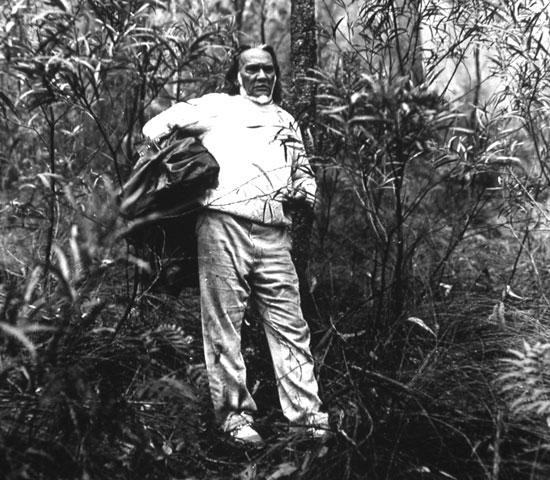

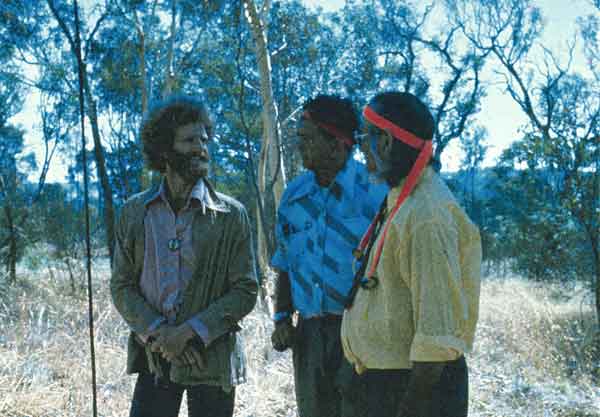

Gubbo Ted, Aboriginal elder, defending areas with sacred sites on Mumbulla Mountain, NSW. 1979, printed 1989 |

|

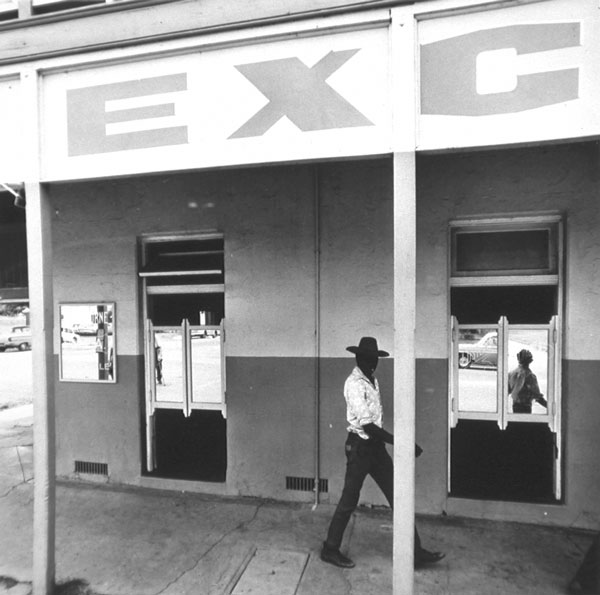

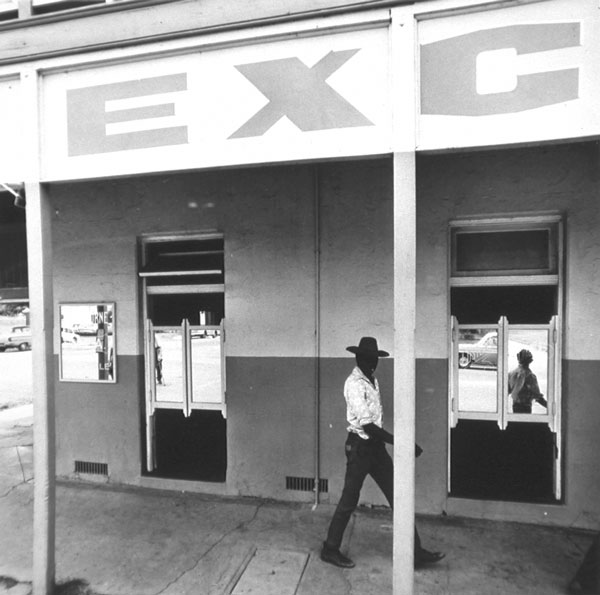

Man and Mirror swing doors, Excelsior Hotel.

1972, printed 1989 |

Playing with titles for a proposed retrospective of his work some years ago, Wesley Stacey came up with 'topographical delights' as a description of his landscapes.

The genre of topographical art reached a golden age in the service of the great scientific voyages and geographical explorations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Topographical art is often distinguished from pure landscape art because of its primary concern with the accurate and precise rendering of permanent features of the landscape, including towns, buildings or ruins.

Atmospheric conditions and the expression of emotions and ideas were not the province of the topographer. Topographical artists were more or less put out of business by the arrival of photography, which took over most scientific recording functions after 1890.

Wesley Stacey sees his work as part of an on-going tradition of 'landscape picture-making' in this country. He perceives his precursors as landscape painters, in particular the leading artists of his youth: Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd and Russell Drysdale. The publication in 1986 of a book on Drysdale's colour photographs, which were taken by the artist on his painting journeys, was a delightful revelation for Stacey.

Features of Fred Williams's landscape paintings - the spareness, countered with the texture of vegetation and the spindly calligraphy of tree trunks - also seem to be echoed in Stacey's use of vertical and horizontal linear elements against a sea of space.

At the same time, Stacey has become more aware of past landscape photographers through the increasing number of photographic publications and exhibitions in the 1980s.

Nevertheless, taken as a whole, Stacey's work - in particular its focus on the enduring aspects of places - has more in common with the topographical artist.

|

|

|

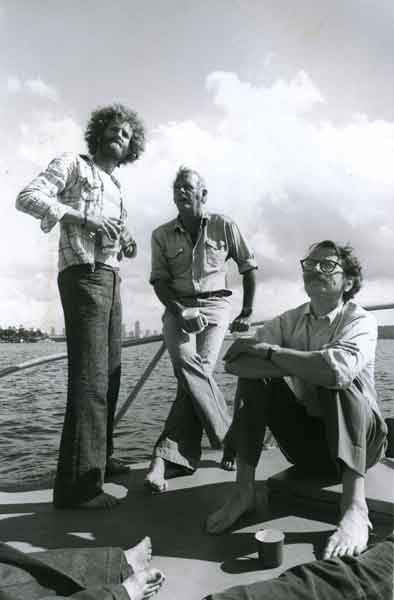

Wreck Bay Sydney Harbour |

|

Fence posts and wire,

near Wollombi, NSW 1961, printed 1989 |

In looking at both Stacey's juvenilia and his graphic work of the early 1960s, the topographer's clarity and linear structures are evident. In these years, Stacey was involved in the Anglican Church and devout in his beliefs.

A certain teenage intensity can be seen in early images that reveal his religious concerns. Barbed wire and steel fence spikes suggest the symbol of Christ's suffering - the 'crown of thorns' - and cosmic symbols such as the wheel and water represent aspects of creation.

Stacey's later rejection of the Church and all imposed doctrines began to show in his work in the early 1960s through a lightness of touch and an openness to new experiences. Dramatic graphic contrasts between black and white spaces and lines, characteristic of sixties art, were modified in the 1970s by a subtle tonal richness.

As a freelance photographer in the seventies, Stacey specialised in travel and architectural subjects.

A series of pioneering publications produced in association with architect Philip Cox on homesteads, vernacular buildings and country towns was novel at a time when the Australian public was still more interested in classical and Georgian colonial architecture.

This publication coincided with a change of attitudes in the National Trust Councils, which were starting to recognize and preserve forms of heritage other than mansions. Heritage protection provided by the Green Bans - activated by that unlikely prophet of environmental consciousness, Builders Labourers Federation boss Jack Mundy - gave the Trust a muscle against the destructive plans of developers. The 1960s and 1970s were also the decades when architect Robin Boyd castigated Australian cities and suburbs as spiritual and aesthetic deserts.

Unlike Boyd, Stacey took a non-judgemental approach to the urban environment with such series as The edge, 1975 - which described Sydney's shoreline suburbs - and The road, 1973-75 - a visual diary of his car trips. At the time, The road was a revolutionary acceptance of the nature and familiarity of the 'driving' experience, and was an innovative expression of a very common Australian approach to the landscape.

Stacey has often been innovative in his career. For example, The road embraced the technical developments of the 1 970s in its acceptance of the character and ease of colour printing and of new cameras such as the Kodak Instarnatic. It revealed Stacey's interest both in process and in extended repetition as a rhythm with its own hypnotic beauty, and also indicated that he was responding to contemporary developments in conceptualist art.

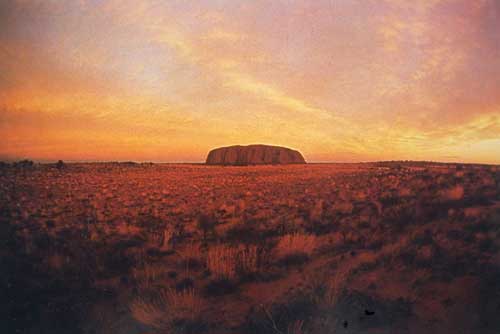

A growing sense of Australian heritage seems to have inspired a significant art event of the 1 970s. In 1972agroupof painters and photographers - including Tim Storrier, Grant Mudford, Melanie Le Guay and Stacey - undertook a pilgrimage to 'The Rock' (Uluru), in the centre of Australia.

|

Broadsound kanga. 1983 |

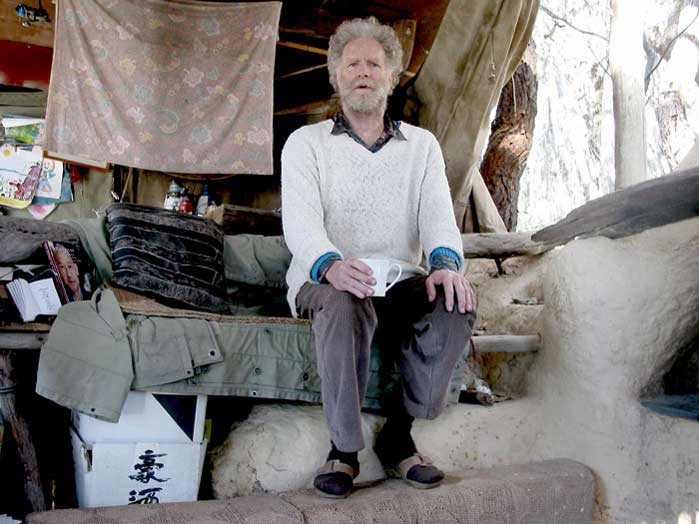

The topographical delights of natural heritage have sustained Stacey from the late seventies. His travels in the 1 980s, in particular, have taken him and his partner Narelle Perroux across the continent - from Bermagui, where he owns land with a bush camp, to Broome and the Kimberleys.

Contacts with Aboriginal people have significantly enriched his view of the land; his adoption of a Widelux camera and his exclusive use of a panoramic format has allowed him a fuller measure of its dimensions.

Stacey's experiences working with the South Coast Advisory Committee on Woodchipping and with Aboriginal tribal elder Guboo Ted Thomas in 1977-80 involved him in the use of photographs for direct social-political protest.

His recent interest in critical discourse on the nature of the landscape arts, such as Paul Carter's study The Road to Botany Bay, has added an intellectual dimension to his concept of the landscape, particularly an awareness of the interpretative role of landscape photography.

Stacey's reading has led him to an understanding of sacred sites of Aboriginal culture and of the breadth and complexity of heritage. Any one site, for instance, can be seen to have aesthetic, historical and spiritual significance.

Stacey's most recent project integrates images created on a trip to Italy in 1988 with photographs from the Australian landscape. Called Signing the land, the images present signs, calligraphy and graffiti found in Italy and dating from the Roman era alongside signs imparted to the Australian landscape by Aboriginal people and early European explorers. What comes across is human presence and cultural commonality.

|

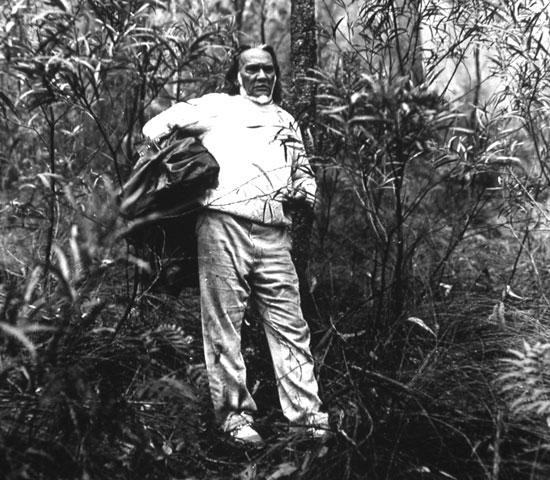

These earlier works of men are almost hidden in a remote gorge in the Carnarvon Ranges. 1984 |

| |

|

| CSR Gas Pipeline country in the Dawson Range. 1984 |

Stacey's landscapes are presented without obvious movement or drama - the land just is.

His images are levelled by a strong horizon, and the panoramic format extends the conventional 'picture window' view that cuts off as much as it frames. In this sense, the topographic tradition - with its clarity and restraint - is an important aspect of his style.

However, in a subtle assimilation that is the essence of his idiom, Stacey's work also incorporates elements of the romantic, classical and picturesque landscape traditions.

Gael Newton was Senior Curator of Photography, NGA, Canberra

Text from NGA Room brochure