A Note on Early Photographic Processes in Australia

As Gold and Silver owes its origin and development to the interpretation of a collection of photographs taken in Australia at a specific date in the last century, it seemed desirable to include a few paragraphs about the history of photographic processes in this country.

I would emphasize that photography is the only accurate recording method, since it is achieved by the action of light upon chemicals, without human intervention. Old engravings and drawings can be both intriguing and historically important, but, considered as detailed records, there is always the likelihood of artistic licence, that one or more of the elements present in the original scene may have been omitted, or perhaps magnified.

A minor example of the former could be suggested: we do not possess an artist's sketch of the customers standing outside Hunter & Co., Herbert Street, Gulgong, in 1872, but if we did, it is surely unlikely that it would include the shapeless black lumps that can be seen on the footpath in plate 135; these are old boots, untidily cast aside by the miners upon the purchase of new pairs.

Photography first came to Australia in May 1841, when, according to the Australian of 15 May 1841, a French visitor bringing the first Daguerrotype equipment to Australia, successfully photographed the western end of Bridge Street, Sydney, from a point near the Francis Greenway Fountain in Macquarie Place. The actual photograph,with its characteristic faint but sharp image on silvered copper, so far has not been located, although the author hopefully searched in the vast collection of the Bureau d'Estampes in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. But, it is interesting that this first Australian photograph should have been taken outdoors by a process which was seldom used outside the photographer's studio.

Professional Daguerrotype portraiture in Australia was initiated in Sydney in I 842 and was continued for about a decade, mainly by travelling photographers. The process was comparatively costly and the market limited. Moreover, each picture called for a separate exposure.

The paper negative process of William Fox Talbot, the Talbotype or Calotype, reached Australia early in the I850s, but, despite the considerably larger format, the unavoidably strong paper texture of the image compared very unfavourably with the exquisite perfection of the Daguerrotype.

This process was superseded in the mid-I850s by the collodion or wet-plate emulsion process of Frederick Scott Archer which, unpatented by its inventor, spread rapidly all over the world. At first, this also was considered a studio process providing a cheaper substitute for the Daguerrotype. Public acceptance was slow, for the collodiotype image was consistently murky — which was only to be expected, for the image was but a pseudo-positive ingeniously obtained by placing a thin negative (i.e. one of low contrast) against a background of black velvet.

The wet-plate process emerged from the studio with the introduction of albumen printing paper, a type of soft printing paper which made excellent prints and multiple copies possible from the contrast negatives of the time.

By the late fifties, leading photographers everywhere were offering extensive albums of general subjects in the comparatively large format of 12" by 15" this in response to a growing demand from a public tired of the formality of engravings. Stock cartes-de-visite could also be purchased of every conceivable subject: art treasures, famous buildings énd familiar landscapes.

This demand continued until the beginning of the twentieth century, when the various processes of the reproductive graphic arts became popular.

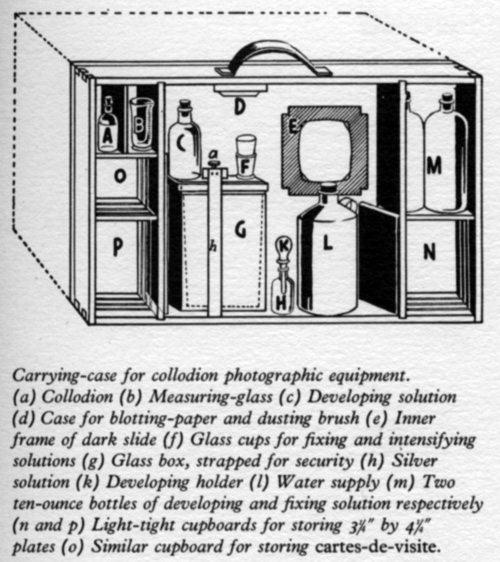

Despite its immense advantages, the collodion process supered from a grave hindrance. This was purely a chemical restriction-the negative had to be coated, exposed while still 'wet', and then processed, all within the space of half an hour, or less, for once the collodion dried out, the silver nitrate crystallized and the image was destroyed.

This requirement brought about the provision of various forms of portable darkroom, originally a folding tent carried in a knapsack or hand-cart by the amateur or travelling photographer. Early in the I860s, the carte-de-visite 'boom' reached Australia and specialist carte-de-visite photographic studios sprang up in a11 towns.

Those living in rural areas were catered for by itinerant photographers who normally travelled with a fully-equipped horse-drawn coating caravan, a darkroom on wheels. The glass for the cartes was of quarter-plate (3¼'' by 4¼") size, but, owing to the exigencies of hand-coating, much of the marginal area was lost, and the finished picture ended up about 2¼'' by 3½''.

Collodion had the advantage of possessing no grain, a welcome feature today in the preparation of exhibition enlargements. The early I880s brought the dry plate, commercially coated and packed, initially in the quarter-plate size, for it was some years before sizes larger than whole-plate became available.

Public taste now turned to the superior quality and more sophisticated appearance of cabinet (4"by 5½'' or thereabouts) studio portrait. The cartes disappeared and, along with them, something of the magic of early photography — people no longer looked so quaint or daily life so Strange.

For an important period of its history, Australia has grown up side by side with photography, and this is a fortunate coincidence for the historian and the sociologist. Certainly it is doubtful whether any other nation possesses a pictorial treasure comparable with the Holtermann collection — so attractively photographed, so miraculously preserved.

>> continues (Holtermann)

Introduction / Processes / Holtermann / Merlin / Bayliss / Iconography / the Plates / Bibliography

The text and notes to the plates: copyright © Keast Burke 1973

The original GOLD AND SILVER plates were taken from the Holtermann negatives, Mitchell Library Sydney.