Australian Pictorial Photography ~ Seeing The Light

Gael Newton AM

Essay originally published in the 2008 catalogue for the Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition:

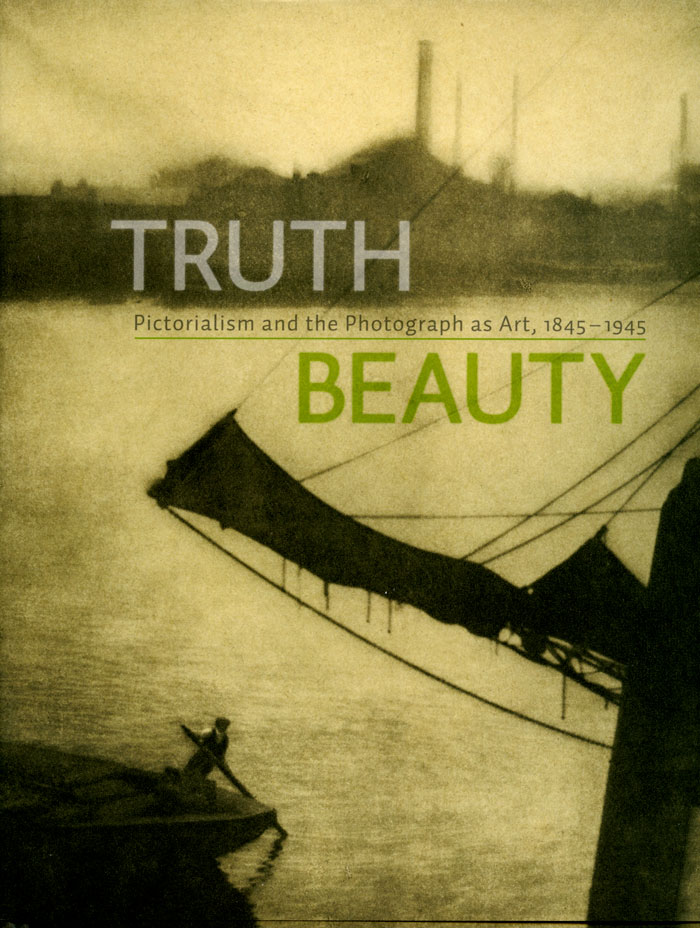

Truth Beauty - Pictorialism and the Photograph as Art, 1845 – 1945

|

| John Kauffmann Waterlily, Nymphaea Alba C.1930 |

Pictorialist Photography, the first international camera art movement, came to Australia in the 1890s and by the turn of the century was adopted with enthusiasm by amateur and professional photographers alike.

Photographers suddenly changed their glossy, sharp prints for pictures made with a variety of matte surfaces, gave the works fancy titles, suffused them with Impressionistic moods and then exhibited them in artistic mats and slim, elegant frames.

A new era had begun.

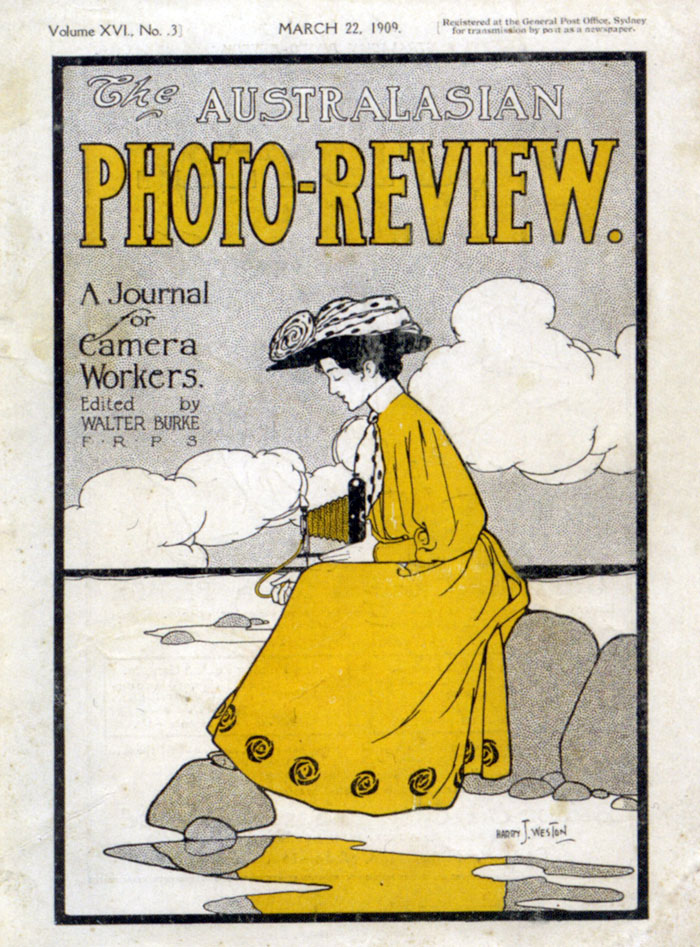

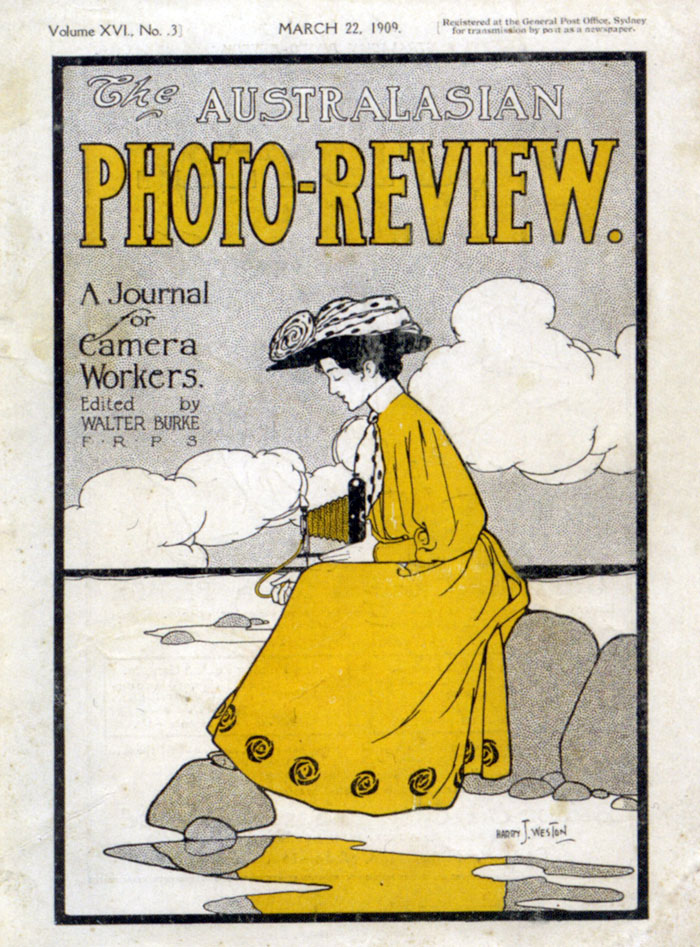

Pictorialism in Australia was established when photographic journals, such as the Australian Photographic Journal (APJ), launched in 1892, and the Australasian Photo-Review (APR), begun in 1894, appeared. 1

In addition to providing technical advice the magazines covered the controversies in Britain and other centres over the new art photography. Articles on poetic picture making by British artists Henry Peach Robinson and Alfred Horsley Hinton, whose names were often cited by Australian Pictorialist photographers as major influences, were also included.

These magazines featured work by both professional and amateur photographers, and their editors took pride in the artistic quality of their reproductions; they also encouraged and supported the growth of new societies devoted to art photography.

The Photographic Society of New South Wales was duly established in Sydney in 1894, joining the older South Australian Photographic Society in Adelaide at the forefront of Pictorialism. The next decades saw a remarkable level of activity in the growing Pictorialist circles.

|

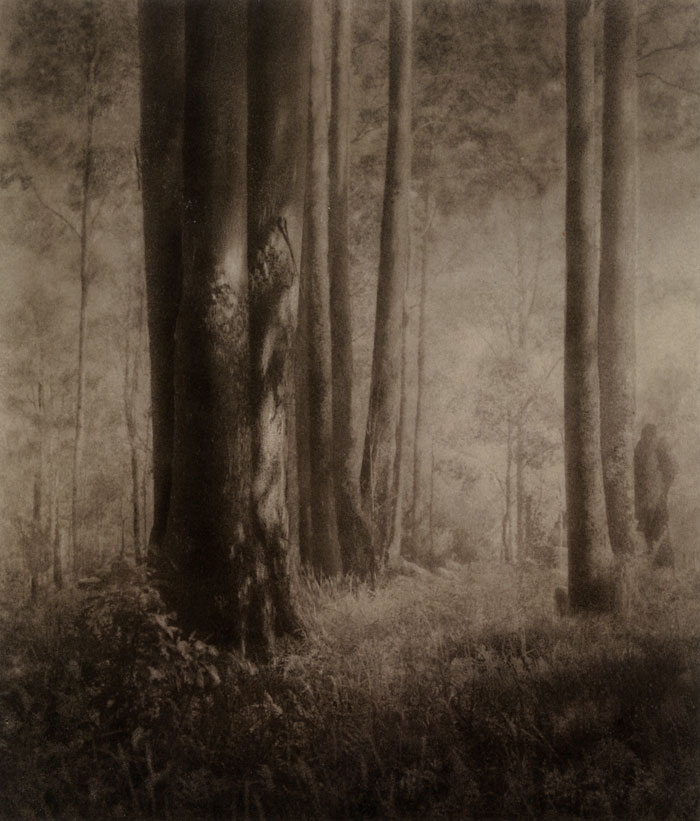

John Kauffmann The Silent Watcher

Plate in in John Kauffmann, The Art of John Kauffmann,

Melbourne: Alexander McCubbin, 1919 tipped-in plate (halftone)

National Gallery of Australia Research Library, Canberra |

A seminal figure in establishing Pictorialism in Australia is John Kauffmann, one of the country's few artists who had directly experienced Pictorialist photography in the centres where it began, having studied in London, Bavaria, Zurich and Vienna between 1889 and 1897.

Inspired by exhibitions at the Photographic Society in London and by the work of Robinson and Horsley Hinton, he studied photography at technical schools in Europe; while in Vienna he particularly admired the work of leading Pictorialist photographers Hugo Henneberg, Heinrich Kuhn, Hans Watzek and those in the Vienna Camera Club. 2

Kauffmann's role as a catalyst for Pictorialist photography upon his return to Australia in 1897 was widely recognized by his contemporaries and later historians.

His atmospheric photographs, very much in the European style, would prove to be highly influential; after moving back to Australia he exhibited his portrait, genre and landscape photographs as bromide enlargements, which the Australian Star praised as "some of the most perfect ever seen" and described as "clear and truly artistic." 3

|

Cover. Australasian Photo-Review vol. xvi, no. 3 March 22, 1909

National Gallery of Australia Research Library, Canberra |

The growing number of societies and camera clubs organized exhibitions and competitions, which exposed photographers throughout Australia to the Pictorialism – a style that early in the century had become synonymous with art photography.

Kauffmann himself was the juror for the South Australian Photographic Society's annual salon in 1901, which was praised and declared by the Register newspaper as the finest ever seen, with some works being "mistaken for works of art," owing to the absence of "all the hard and sharp usually associated with photography." 4

The society's 1903 salon featured over five hundred photographs, including a small selection of international works.

In 1905 the Amateur Photographic Association of Victoria, affiliated with the Royal Photographic Society, mounted an exhibition of Pictorialist works from the body in London.

Through an active program of exhibitions, Australian artists had the opportunity to see work by their Pictorialist brethren from throughout Australia, and increasingly, from their international contemporaries; Australian photographers were amazingly energetic exhibitors abroad as well, dispatching prints by lengthy sea mail to the network of Pictorialist exhibitions in Europe and America.

The largest salon of that period was the 1917 Exhibition of Australian Pictorial Photography featuring the work of hundreds of practitioners across the country and representing dozens of camera clubs. It was billed as the first dedicated Pictorialist show in Sydney and lauded for the number of works showing "typical Australian atmosphere" and the lack of extremes of "fuzzy" images. 5

To appreciate the degree to which Pictorialism as the dominant style thrived in Australia long after it waned in other centres, is to remember that this landmark exhibition took place eight years after Alfred Stieglitz had renounced Pictorialism and the British Brotherhood of the Linked Ring had disbanded.

|

Harold Cazneaux's "One Man Show" at the New South Wales Photographic Society Rooms in Sydney 1909

Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1982, Gift of the Cazneaux family, 1981 |

The Pictorialists sought to have photography recognized as a fine art, and, concomitantly, themselves as artists. A new level of public awareness of the photographer-as-artist would come in 1909 when Harold Cazneaux held the first one-person show in Sydney, followed in the same year by one devoted to the work of John Kauffmann in Melbourne.

Such shows were still a novelty for painters, let alone photographers.

Kauffmann was praised for such photographs as The Marquee (1910), an enigmatic evocation of a leisurely summer gathering worked in a naturalistic but atmospheric style.

As this bromoil print attests, Kauffmann's pigment printing was less heavy handed than much of the work he would have seen abroad; it is interesting to note that Australian artists in general eschewed the use of extreme soft focus, what some bemused contemporaries termed the "fuzzy wuzzy" school of photography, preferring a more straightforward approach (even in manipulated images) that avoided the penumbra of light and extremes of soft focus often seen in other Pictorialist centres.

Cazneaux had originally wanted to be a painter but, while working as an artist-retoucher in an Adelaide portrait studio around 1900, was converted to the "new beauty of the camera" after seeing Kauffmann's work in the exhibitions of the South Australian Photographic Society. 6

He moved to Sydney in 1904, bought a small camera and joined the New South Wales Photographic Society. An early work such as Orphan Sisters, a circa 1906 study of his cousins, displays Cazneaux's sophisticated understanding of Pictorialist tonal practice and is an example of the accomplished portraiture that would dominate his 1909 show.

Unlike many of his Pictorialist colleagues who carefully composed their subjects in the studio, Cazneaux soon favoured the outdoors, using his hand-held camera to shoot Impressionistic views of the Sydney cityscape and surrounding countryside.

|

James Stening, The pioneer 1904 |

Frank Hurley also preferred to work outside the studio. A postcard photographer in Sydney beginning around 1905, Hurley was one of the first to apply Pictorialist style to a commercial product.7

Safe at Anchor, a rare exhibition print of one of his moody postcard images of Sydney Harbour and surrounding districts shot at twilight, was made before he was appointed as the official photographer to Douglas Mawson's British-Antarctic Expedition in 1910.

Hurley was one of the few Australian Pictorialists to work outside of the country; he would later apply the principles of dramatization and manipulation he learned from Pictorialism to his various Antarctic and New Guinea expeditions.

Portraiture was a rich genre of Pictorialism in Australia and flourished in the commercial studios of many of the art photographers. It was also a genre in which a number of the new generation of independent modern women specialized.

New Zealand-born sisters May and Mina Moore had a studio in Wellington before moving in 1910 to Sydney where they established a studio (opening a second in Melbourne in 1913). The sisters became known for their dramatically lit portraits of figures from the world of theatre, often in costume, as well as notable writers, musicians and artists.

World War I brought innumerable changes to the continent. Australia had ceased being a British colony in 1901, but it was the losses suffered by Australian troops in World War I, especially those at Gallipoli, that stirred a new national consciousness concretized in the first celebration of anzac day in 1926. 8

The field of art was no exception. In 1901 A. Hill Griffiths, the Australian correspondent for Photograms of the Year, had presciently written, "I deem it an unpardonable error to depict Australian scenes with uncharacteristic English mists." 9

His was an early voice calling for Australian artists to develop a style of their own.

In the years leading up to the war there was growing sentiment that Australian photographers were overly reliant on British models and had failed to advance the art of pictorial photography within an Australian context. A number of the more prominent Australian photographers and art commentators were also increasingly vocal about what they felt to be a decline in the quality of artistic practice despite the feverish activity of exhibitions and proliferation of camera clubs.

In 1916 a group of artists including Cazneaux, Cecil W. Bostock, a graphic artist who had recently set up a photography studio in Sydney, and James Stening formed the Sydney Camera Circle. They signed a pledge “to advance pictorial photography and to show our own Australia in terms of sunlight rather than those of greyness and dismal shadows.” 10

|

Unknown photographer - Sydney Camera Circle Members;

first Australian Salon of Photography meeting in Sydney march 30, 1924

From left to right: W.S. White holding print, Monte Luke at easel, James Paton, Harold Cazneaux, Stanley Eutrope,

Charles Wakeford, Websterwith pipe, ArthurSmith. In front: J. McColl, Cecil Bostock.) gelatin silver print

Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1984, Gift of Cazneaux family, 1984 |

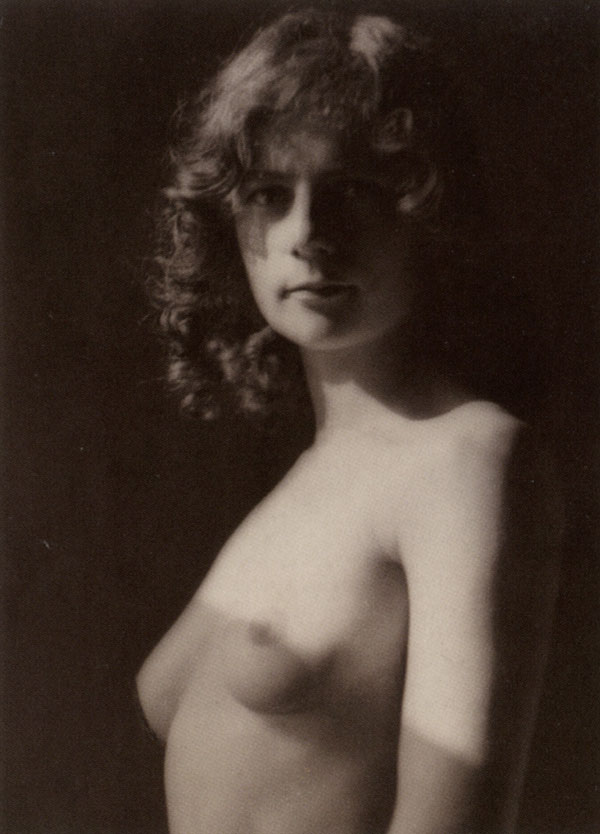

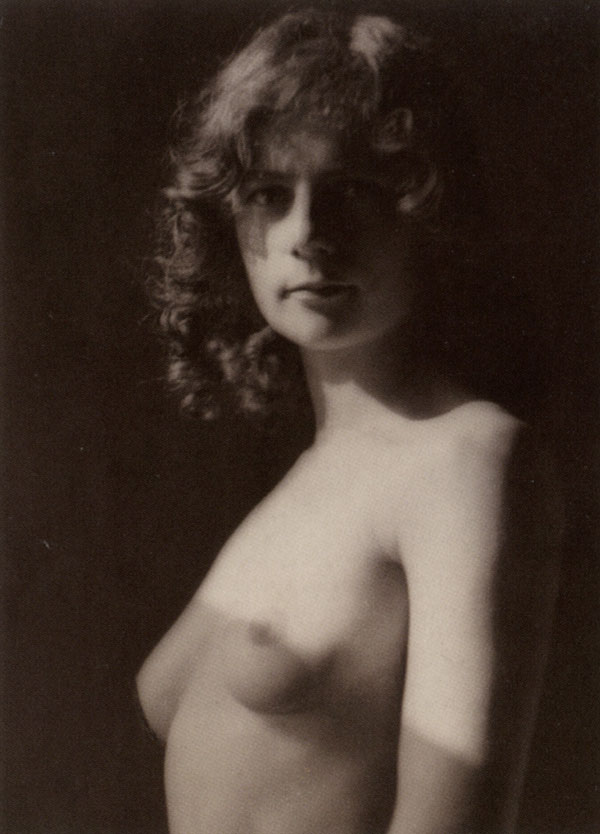

Cazneaux and Bostock became the driving forces behind the search for a national style. In 1917 Bostock published twenty-five hand-bound copies of his A Portfolio of Art Photographs. This featured ten tipped-in sharp-focus and unmanipulated photographs, including Nude Study, a startlingly direct portrait and one of the only nudes made in Australia before the mid-1930s.

Although the dramatic use of light may recall earlier Pictorialist work, such as that by the Moore sisters, Bostock was clearly working in a more pared down, Modernist vein, and his interest is the sculptural forms of his subject's face and body, not the particulars of her visage.

Also noted for his dramatic portraiture was Jack Cato, who went to work in London in 1909 for the expatriate Australian H. Walter Barnett, then the most famous artistic portrait photographer in London, and returned to Australia in the 1920s to run one of the best-known portrait studios in Melbourne.

In works such as Snorky, Cato retained the Pictorialist penchant for character studies – capturing in this uncommissioned study a street character in Hobart – and reveals a stylistic debt to Barnett and to London photographer E.O. Hoppe, known for his use of strong lighting and unconventional poses. 11

By 1914 Kauffmann had become a commercial photographer in Melbourne. In 1919 he published The Art of John Kauffmann. The first monograph on a photographic artist in Australia, it included twenty landscapes (as well as some urban scenes) featuring dramatic and distinctively Australian trees to which he appended patriotic titles.

Like others at this time, Kauffmann was answering the call to show his nationalist spirit in tandem with the universalist idealism of Pictorialism.

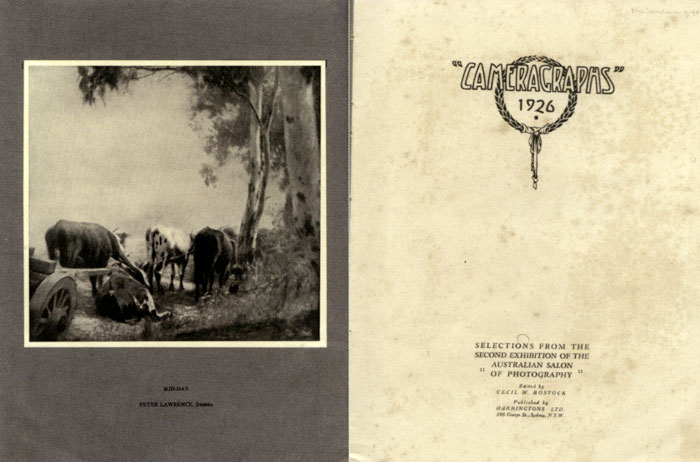

Although it had largely waned in Europe and the United States by then, Pictorialism continued in Australia during the 1920s and 1930s. There was a new generation of artists showing their work alongside that of their more established colleagues in two large Pictorialist salons held in Sydney in 1924 and 1926 accompanied by catalogues called Cameragraphs (designed by Bostock). Perhaps because of the Depression, these salons did not continue.

Beginning in the 1920s Pictorialist and Modernist photography existed side by side with the professional photographers bridging both movements. Pictorialist photography would remain popular, particularly with the amateur members of the camera clubs up to the 1940s, ironically becoming increasingly conservative and backward looking in subject and execution.

However, the ascendancy of Modernist photography was now evident, even in the work of Cazneaux and Bostock, who would become active in the 1920s in commercial spheres.

Cazneaux was chief photographer for the popular magazine The Home. Bostock took fashion photographs for the David Jones Store and did work for engineering and industrial firms.

Although hardly Modernists, both artists began to incorporate into their Pictorialist aesthetic the clearer outlines, patterning, flat planes and geometric details deriving from Modernism, Art Deco and contemporary German photography.

Cazneaux completed a series of photographs in 1930 documenting the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, celebrating the structure's bold patterned-steel form and contrasting it with the now anachronistic tenements nearby.

Unlike earlier cityscapes, such as John B. Eaton's soft-focus Wet Day in Melbourne, architecture is the subject in Cazneaux's series – specifically a bridge that instantly became an icon of Australian modernity – not merely atmospheric Pictorialist effects.

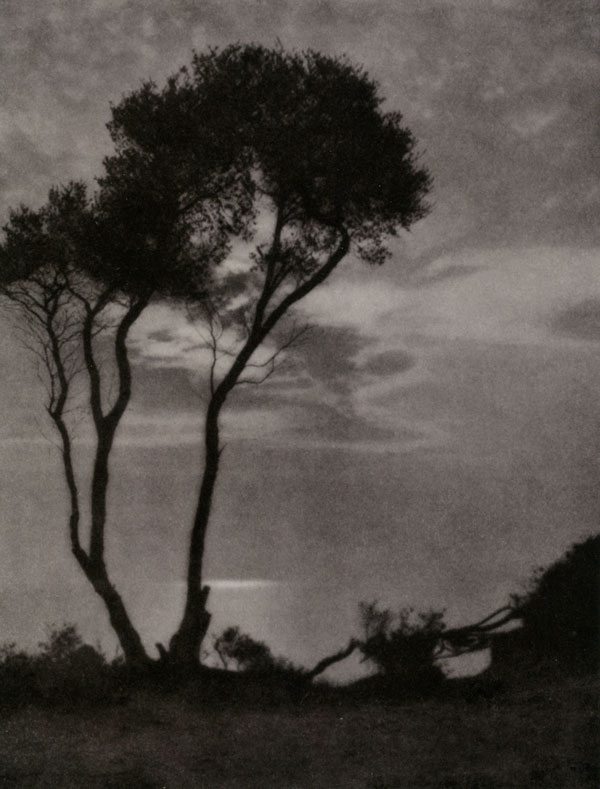

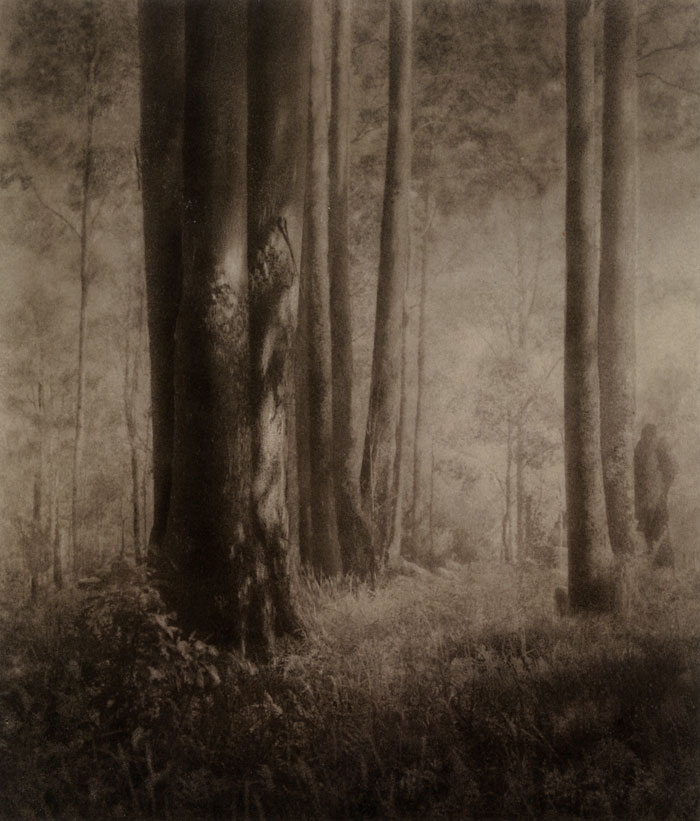

Rose Simmonds and Olive Cotton were highly successful women active from the 1920s and 1930s, respectively, both of whose work shows a reverential approach to the Australian landscape. Tall and Stately, one of Simmonds's landscapes from the 1930s, shows the artist's remarkable ability to capture the light and atmosphere of a forest in this image reminiscent of Barbizon painting.

As a young member of the New South Wales Photographic Society, Olive Cotton had known Cazneaux; in the 1930s her work increasingly showed the influence of Modernism. Grass at Sundown displays the poetic mood, soft focus, asymmetrical composition and dramatic lighting that are hallmarks of Cotton's approach. As many artists would now do, Cotton perfectly fused elements from both Pictorialism and Modernism into her own singular style.

|

Frontispiece of the catalogue of the second Australian Salon, 1926,

designed and edited by Cecil Bostock showing Peter Lawrence's bromoil print, Mid-Day

National Gallery of Australia Research Library, Canberra |

Photographs displaying Modernist formal styles began appearing in Pictorialist exhibitions in increasing numbers from the early 1930s.

The rise of a more strictly Modernist style antithetical to the Pictorialist school in Australian photography can be marked by the publication in 1935 of Art in Australia. These were a suite of Surrealist and Modernist inspired photographs by Max Dupain, the young apprentice of Bostock who opened his own studio in 1934.

On the occasion of Australia's sesquicentenary celebrations in 1938, Dupain expressed disgust and frustration that the work on view in the 150th Anniversary International Commemorative Salon (of which Cazneaux was an organizer) was not an up-to-date view of the new photography in Europe.12

|

|

|

| Cecil W. Bostock Nude Study c1916 |

|

Jack Cato, Snorky 1924 |

Although Modernism as championed by Dupain would become ascendant, it did not spell the end of Pictorialism. In truth a hybrid Modernist Pictorialism had developed and would continue to generate works of power and importance.

Cazneaux's last major works, for example, were mid- to late 1930s studies of industrial scenes, in a series commissioned by BHP mining company of its Australian steel working plants, and grand landscape studies of central Australia.

Indeed, what the best works of this type by Cazneaux and his contemporaries achieve is a kind of quietly spiritual depiction of the magic and essence of the country that rings true for an Australian audience well beyond the original Impressionistic models of art photography inherited from Europe.

Notes

- After 1910 Australian Photographic Journal was published as Harringtons' Photographic Journal.

- From an interview with Kauffmann while he was visiting Sydney, reported in the APJ of December 20, 1907:

"[Kauffmann] has had the opportunity of studying the works of advanced Pictorialists, both on the Continent and in England. Inspired by their aims, he found the camera held a new meaning for him, and he indefatigably sought for technical perfection of method, so that he could render nature according to his own lights.

He acknowledges being largely influenced by such powerful workers as Drs. Hennebergand Spitzer, Hans Watzek, Heinrich Ktihn, and other leading members of the Austrian school, which school, at the present time, holds an unique position for strength and originality amongst the great pictorial schools of the world..."

- The Australian Star, October 8,1897, P. 2.

- The Register, October 19,1901, p. 7.

- J.T. Farrell, "Editorial," Harringtons' Photographic Journal, November 20,1917.

- Harold Cazneaux wrote a series of letters to photographic historian Jack Cato in the early 1950s in which he gave several accounts of his epiphany with Pictorialist photography in Adelaide. The exact letter in which he spoke of the new beauty of the camera has not been located. The letters are held by the National Library of Australia (ms 5416). In his reminiscences Cazneaux almost certainly merged several exhibitions in Adelaide together, and these were probably the salons of 1901 to 1903.

- Hurley was not the first commercial photographer to apply the new art style to commercial work. L.W. Appleby, a Sydney professional portrait photographer, had introduced gum bichromate portraits against neutral backgrounds and had a show of these in Sydney in 1903.

- Anzac Day—April 25 — is probably Australia's most important national occasion. It marks the anniversary of the first major military action fought by Australian and New Zealand forces during World War 1. ANZAC stands for "Australian and New Zealand Army Corps."

- Hill Griffiths, "A Letter from Australia," Photograms of the Year, 1901, p. 30. Griffiths was editor of the APJ

- The original group consisted of Harold Cazneaux, Cecil Bostock, James Stening, W.S. White, Malcolm McKinnon and James Paton. By the end of 1917 another dozen members had joined, including Monte Luke, Henri Mallard, D.J. Webster, Charles E. Wakeford and Arthur Ford.

In 1921 a Japanese artist, Kiichiro (or Kihei) Ishida joined the group and was presented with a large collection of prints by circle members on his return to Japan in 1924. See Yuri Mitsuda, Modernism/Japanism in Photography 1920S-T940S: Kiichiro Ishida and Sydney Camera Circle (Tokyo: Shoto Museum of Art, 2002).

- After retirement in 1947 Cato wrote the autobiography I Can Take It and the first history of photography in Australia, The Story of the Camera in Australia (Melbourne: Georgian House, 1955). The work chiefly lauded the role of professional photographers such as himself but also presented Pictorialism as one of the great achievements of the modern era ignoring Modernists and documentary photographers perse.

In 1930 the German-born Emil Otto Hoppe travelled across Australia gathering pictures for what would be a landmark photo book called The Fifth Continent (1931). An exhibition of his portrait, travel and industrial photographs in April 1930 may have influenced Sydney photographers. The prints were unusually large and both Modernist and Pictorialist in style — particularly his industrial images.

See Graham Howe and Erika Esau, E.O. Hoppe's Australia (New York: Curatorial Assistance in association with W.W. Norton, 2007).

- See Gael Newton, Max Dupain: Photographs 1928-1980 (Sydney: David Ell Press, 1980), p. 28.

|

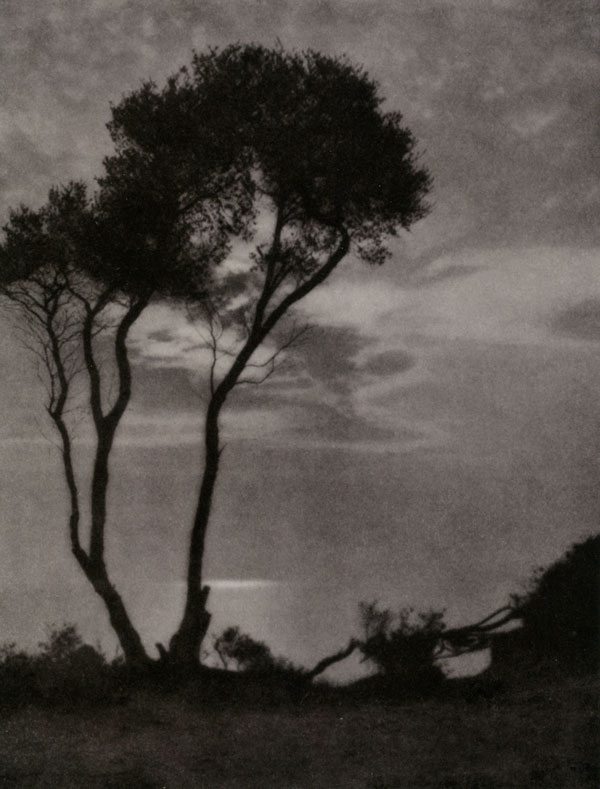

| James Stening, Australian River Oaks, C.1898–1900 |

|

Olive Cotton, Grass at Sundown, 1939 |

| |

|

| John B. Eaton, Wet Day in Melbourne, 1920 |

| |

|

| Harold Cazneaux, Slag Dump, Newcastle (NSW), 1934 |

| |

|

| Rose Simmonds, Tall and Stately, C.1932 |

| |

|

| Frank Hurley, Safe at Anchor, 1909 |

| |

|

| Harold Cazneaux, The Orphan Sisters, C.1906 |

| |

|

| May and Mina Moore, Portrait of an Actress, C.1916 |

|

|

|

| Catalogue Front cover |

|

back cover |

Publication essays

Director's Forward - Kathleen S. Bartles

Crafting the Art of the Photograph - Alison Nordstrom (Curator) and David Wooters

Arts Una, Species Mille: Pictorialist Photography in the Czech Lands - J. Luca Ackerman

Pictorial Photography in Japan - Ryuicki Kaneko (translated by Wataru Okada)

Australian Pictorial Photography: Seeing the Light - Gael Newton

Readings in the History of Pictorialism - Jessica S. McDonald, editor

Link to the gallery shop for the publication details

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|