A PHOTO-LITERATE GENERATION

Gael Newton

Essay for the catalogue Tom Roberts, NGA exhibition 4 December 2015 – 28 March 2016

As a painter Tom Roberts valued works of art that had 'a marvellous seeming reality', and he stated that a 'painting fixes one thing for you - one scene, one mood, one idea'.1

His much-loved major works are most notable for their sense of a moment in time and atmosphere - sometimes guiet, sometimes full of action - that we intimately share with his sitters and scenes. That quality of immediacy and actuality, and the artist's choice of words, could just as easily describe a photograph.

One myth needs first to be laid to rest. In his 1935 posthumous biography Tom Roberts: father of Australian landscape, the journalist Robert Croll claimed that Roberts, while working as a camera operator at the fashionable Bourke Street studio of Stewart & Co. in the 1880s, introduced a style of native foliage and naturalistic bush settings that became a fashion in Australian studio portrait photography. No source is given by Croll, but Roberts never made that claim and said little about his early career in photography.2

In 1955, Melbourne professional photographer turned writer Jack Cato published The story of the camera in Australia and, while quoting from Croll, Cato does not repeat Croll's claim in his own account of Roberts as a camera operator in the employ of Stewart & Co.

Cato dismissed Roberts' influence as a photographer and, indeed, the rustic studio settings that Croll identifies as Roberts' legacy were common internationally and in Australia by the mid 1880s. Examples with overtly Australian foliage are, however, exceptional including in Stewart & Co.'s output.3

Perhaps knowing of Roberts' love of the bush and habit of bringing bunches of gum leaves home, and a dedicated bushwalker himself, Croll made an imaginative inference from Roberts' early career in a portrait studio.

What then might be Roberts' debt to his early career in a photographic studio and to the medium in general, in the late 19th century? Growing up in the 1860s, Tom Roberts was part of the first photo-literate generation, and he and his contemporaries lived to see the development of the modern media world of still and moving photography. As the ubiquity of photography impressed itself on society and the arts, Roberts' painterly practice cannot but have been influenced to some degree, technically and aesthetically, by the nascent photographic technology and techniques.

While his best works share the dynamic of a moment captured or the compressed space and varied perspectives of late 19th-century outdoor photography, Roberts did not need expertise with a camera to be imbued with the exactitude of the photograph or its 'slice of life' spontaneity.

As the son of the editor of the Dorchester Chronicle, Roberts would have been alert to new developments in communication. Local photographer John Pouncy, for example, issued the world's first photo-lithographically illustrated book on Dorchester in 1857.

Roberts' son Caleb reported that his father's first art activity had been colouring in woodcut illustrations in The Illustrated London News - many of which were, by the late 1860s, drawn after photographs. |

|

|

Tom Roberts, Dorcester c 1867 albumen silver photograph, private collection

|

| |

| |

|

RC. Burman Emma Minnie Rippon c1872 albumen silver carle de visite photograph, State Library of Victoria, gift of Mr Jon Elkins

|

|

By 1900, photomedia permeated society and all forms of visual communication and the arts, and had created a taste for a new range of images of contemporary life.

The untimely death of his father in 1868 prompted Roberts' mother to migrate to Australia, where his first job as a teenage emmigrant was as an assistant in a photographic studio in Smith Street, in Melbourne's Fitzroy in 1871. Roberts recalled his first job in a photo studio as Dickensian hard labour; it must have seemed like a come-down from the studies and career paths that had been open to him in England. The conseguence of this employment, however, was that Roberts' experience with photography was more direct than for most of his artist contemporaries in Australia at the turn of the 20th century.

Roberts did not name his first employer, but it is believed to be the Fitzroy Portrait Rooms,4 which were owned by Frederick C. Burman (1841-1927), who came from an English family of decorators turned photographers with studios in several Melbourne locations. The State Library of Victoria holds some photographs with Burman's Smith Street imprint. Of a standard common to studio portraiture worldwide in the 1870s, they include an occasional fancy backdrop, maybe a dot of colour, but few props or poses. It was hardly an inspiring environment for an aspiring young artist, who had begun to take night classes in drawing.5

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Stewart & Co. Group of four women c1885 albumen silver photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

|

|

Stewart & Co. Portrait of a young boy in a rustic landscape albumen silver carte de visite photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, gift of Nigel Lendon

|

While Burman advertised a range of services, Roberts is unlikely to have worked outdoors on city or landscape commissions although he may well have absorbed lessons in portrait posing, lighting and managing sitters. The large studios of the day had a strict division of labour and Roberts was not necessarily involved in the printing side of the studio business, even though by the early 1880s the messy wet-collodion processing had been overtaken by far easier dry-plate processing. Camera operators took the pictures and coaxed the sitters into the right attitudes, aided by others helping with props, lighting and posing, using braces to hold the sitters in position. Backroom assistants developed and printed the glass plates, and artist-retouchers and colourists glamorised the final print. All the prints were produced under the studio name.

An ambition to work in a studio producing a better class of work might have been the prompt in 1877 for Roberts to join the upmarket city studio of Stewart & Co. 'photographers, miniature and portrait painters', which was located in the theatre district of Bourke Street east. The owner, Englishman Robert Stewart (1838-1912), was a professional photographer who relocated from Sydney to Melbourne in 1871.6

The firm was associated with smart portraits of theatre performers and rapidly became a large establishment. It would have been an exciting place to work and, apart from the period between 1881 and 1884 that Roberts spent studying painting in Europe, he worked for Stewart & Co. until 1889.

|

|

|

Stewart & Co. Portrait of a young woman in a bonnet c1880 albumen silver carte de visite photograph, private collection

|

|

Stewart & Co. Miss Fiorrie Forde and her sister c 1892 [Flora Flannagan, music hall artist and sister or partner, in 'Ford Sisters' in Japanese costume] albumen silver photograph cabinet card, courtesy State Library of Victoria

|

Robert Stewart was a consistent supporter of Roberts as an employee and an artist. He encouraged Roberts' trip to Europe and presented him with a farewell chegue. The firm's support continued under studio manager Andrew Barrie (1860-1937), who became managing partner and then owner. In 1885, Barrie offered Roberts a part-time job arranging backdrops, props and poses.

This gave the young artist the financial security to pursue painting during his time off.7 Barrie had emigrated from Scotland at an early age and was already a skilled amateur photographer in his teenage years.

Roberts did not work as a professional photographer and his level of expertise with a camera is unknown.8 There are no positively identified portraits taken by him, nor any for which he arranged props and poses or painted backdrops. He left only scraps of information about early photographic studio work and no public comment on photography as an art in its own right, despite undoubtedly having been aware of the active art photography movements in Europe and Australia from the 1880s on.

A more likely influence on Roberts was that, by the mid 1880s, Stewart & Co. had established a reputation for natural-looking portraits that were superior to the general run of studio portraiture. Their group portraits could be remarkable for their informality, and some portraits of self-assured young ladies are reminiscent of the poses adopted in the commercially available portraits of actresses.

As a portrait painter, Roberts captured a sense of the person in a particular moment in time, an effect that was facilitated in photographic portraiture by the shorter exposure times of late 19th-century photography. While Roberts' sitters do not have the unmistakable gaze-to-camera 'look' that is common in a painting made from a photograph, the experience of working intensively in a photographic portrait studio can only have informed, to an extent, his later execution of lively, naturalistic informal portraits. As a painter, Roberts valued realism.

In general, Roberts applied himself energetically to sketching from life for his major works featuring activity taking place in the Australian bush, such as Bailed up 1895/1927 (cat 71), Shearing shed, Newstead c1894 and A break away! 1891 (cat 55). The representation of animal and human movement, which he integrated from his extensive drawings from life, is a feature of several of Roberts' major works. His knowledge of Eadweard Muybridge's 1880s series of time-lapse photographs of animals and humans in motion was enhanced when he attended a lecture on Muybridge's work at the Buonarotti Club in Melbourne in September 1886.9

|

|

|

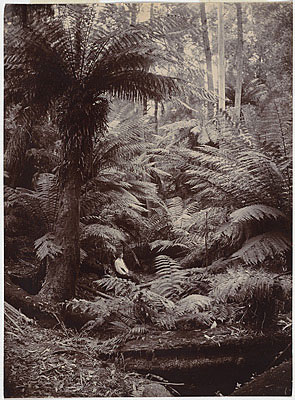

Nicholas Caire Fern gully ot Gembrook c 1896 albumen silver photograph, 20.4 x 14.9 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

|

|

Nicholas Caire. Making polings in the forest, Fernshow, Victoria c1885 albumen silver photograph, 13 x 18.3 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

|

Roberts' studio exhibitions in the 1890s were noted for their theatrical setting of lush patterned materials, foliage and Japanese props. Such backdrops are seen in a few Stewart & Co. portraits: Japonisme was in the air and the Gilbert & Sullivan musical The Mikado was staged in Melbourne in 1886.

Roberts shared a long friendship with a fellow employee at Stewart & Co., the flamboyant, H. Walter Barnett (1862-1934), who went on to have a successful career as a vice-regal and society portraitist with studios in Australia in the 1880s and 1890s, and London from 1895 to 1920, and worked in the new art photography style of glamour portraiture.10

Roberts' scepticism about photography as art, however, might be gleaned from comments in a letter to his friend S.W. Pring in April 1895, that 'a painter needs to be able to form his own idea of the subject - that's hardly possible with a photograph'.11 Barnett, who claimed to have arranged the first sale of a painting by Roberts in 1881, was later a buyer of his work. These friendships with photographers might have led to Roberts' reticence in any public comments on photography as art. Egually, as a photograph in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, attests, Roberts' had reason to be grateful for Barnett's skill as a portrait photographer.

Barnett's portrait of the DuAre of Cornwall and York (later King George V) 1903 is clearly marked by several fingerprints in a light oil paint. There is good reason to speculate that the prints belonged to Roberts himself, who is known to have used several Barnett portraits in preparation for the major group portrait of 1903 commemorating the opening of the first Federal Parliament on 9 May 1901 (cat 101). The Federation project was an immense undertaking for which Roberts was commissioned to capture on canvas over 250 likenesses of the dignitaries who assembled on that auspicious day. It is known that Roberts was frustrated by a lack of sittings with the Duke and it is likely he used the photographic image to aid in his portrayal of this sitter, and perhaps others.

Thus, like most artists and illustrators of the period Roberts made use of photographs as a tool in support of his paintings, in preparation for which he mostly sketched from life. The closest correspondence between Roberts' work with a local photographic genre is in some of his bush and beach scenes and the contemporaneous new school of picturesgue landscape photography of the 1880s, which gathered in popularity in the years leading up to Federation in 1901.

Roberts would have noted the rustic bush idylls showcased in the Collins Street studio windows of landscape specialists Nicholas Caire and J.W. Lindt in the 1880s. This imagery catered to a new class of daytripper, also depicted in Roberts' works, whose recreational use of the landscape could be recast in a new national narrative. As the 19th century drew to a close, artists, regardless of their origins and the medium used, were expressing a sense of their time, place and nationality as Australians.

Beyond the local realm, a guest for photographic exactitude and vivid three-dimensionality had precedents in various forms of illusionistic painting of the 19th century, including that of the detailed tableaux of the Pre-Raphaelites in England in the 1850s. The naturalist school of painters, including Jules Bastien-Lepage in France, was a direct inspiration for Roberts. By comparison, however, he is less 'photographic' than Bastien-Lepage, especially in regard to the latter's social realist images where the viewer is transfixed by the material presence of the figures, their clothes and gaze, which freguently looks 'straight to camera'.12

Despite considerable scholarly scrutiny in recent decades,13 Roberts' oeuvre shows no decisive advantage gained from his direct experience with commercial photography. There are, however, photographic aesthetics derived from broad trends of late 19th-century painting present in Roberts' work. The French Impressionists of the 1860s valorised images painted from life that strove to capture a fleeting moment of the urban or pastoral scene, and drew on the new dynamic of decentred camera vision and blur. These compositions have the effect of rapid action, as exemplified in the 'snapshots' realised by photographic developments of the 1880s. But these small monochrome photographs of the period were hardly competition and, indeed, paintings seem to capture action more effectively than the snapshots.

Roberts' work as a photographic assistant brought him into unigue contact with an alternative means of creatively and realistically representing and recording the world. Artists consume source imagery like bower birds and, as a painter, Roberts drew what he needed from the models and practices of his era to achieve a rendition of the life and landscape of Australia that best resonated with his own affection for, and appreciation of, his adopted land.

- Argus, 31 Oct 1891, cited by Leigh Astbury, City bushmen: the Heidelberg School and rural mythology, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, New York, 1985, p 120; Croll, 1935, pp 56-7.

- Croll, 1935, p 4. Croll's 1939 memoir / recall: collections and recollections, Robertson & Mullins, Melbourne, 1939, mentions hearing stories about Roberts from Melbourne professional photographer Jack Cato at the Savage Club - the stories, however, came after the publication of his 1935 book on the artist - Cato only having become a member of the club in 1936. For Cato, see Gael Newton, 'Cato, John Cyril (Jack) (1889-1971)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cato-john-cyril-jack-9712/text17147 published first in hardcopy 1993.

- Findings based on the author's online image survey and consultation with a collection of some 200 Stewart & Co. cartes de vlsltes and data from the collection of Warwick Reeder, Melbourne.

- Mary Eagle made this deduction on the basis that Burman had the only studio in Smith St between 1871-77 the period of Roberts' employment; Eagle, 1997 p 112.

- Croll, 1935, pp 3-5.

- The claim by Jack Cato that Robert Stewart was Scottish (with the first name of Richard) is incorrect (The story of the camera In Australia, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1955, p 88). Stewart was born in Middlesex and his obituary by H. Walter Barnett's Falk Studio in the Australasian Photo-Review asserts that he came to Australia to seek work as an architect but turned to photography, sending for his camera from home and thus indicating that he was already expert in its use (22 Aug 1912, p 469). His brother, Walter Salter Stewart, is known to have worked in Australia before going to New Zealand. See the entry for Robert Stewart, Design and Art Australia Online, www.daao.org.au/bio/robert-stewart/ personaLdetails/?. A painting by Roberts was purchased by Stewart and passed on to his descendants. It was possibly not an original but the copy of Edwin Long's Dancing girl (NGV) (Hugh Sloane (descendant), correspondence with the author, June 2015).

- Croll (1935, p 23) refers to an offer from 'Barrie & Brown'. No studio of that name is listed as having operated in Melbourne, but Andrew Barrie's wife Elizabeth Brown was the co-proprietor of Stewart & Co. and an owner of Barroni & Co. studio. Barrie went on to be a wealthy and influential Melbourne businessman who acted as a judge in photography competitions until the mid 1930s. Information courtesy Andrew Barrie (great-grandson of Andrew Barrie), correspondence with the author, Feb 2015.

- As McQueen notes, 'Photography never attracted the artist in Roberts and so he never mastered the medium' (McQueen, 1996, p 144).

- Muybridge's animal locomotion time-lapse photography was widely published from the mid 1880s, see discussion of animal depictions in Astbury, 1985, pp 113-21 and McQueen, 1996, pp 334-9.

- In researching The story of the camera In Australia in the late 1940s, Jack Cato interviewed the elderly Arthur Peters, a former printer at Stewart & Co., who later managed Barnett's Falk Studio in Sydney. Peters reported that he had been assistant to Roberts as camera operator, and that Stewart had him clear out an attic for Roberts to use as a studio (Cato, 1955, p 88).

- Roberts, letter to S.W. Pring, 7 Apr 1895, (ML 1367). McQueen also observes that Roberts believed that 'oil paint offered entry into dimensions of personality not obtainable through photography' in line with guasi-scientific views about the face mirroring the soul, http://www. surplusvalue.org.au/McQueen/roberts/roberts_panels.html.

- For a detailed discussion of relationships between naturalism, photography and film, see G. Weisberg (ed.). Illusions of reality: naturalist painting, photography and cinema, 1875-1918 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; the Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, Mercatorfonds, Helsinki, Brussels, 2010). See also Leigh Astbury 'Tom Roberts's Shearing the rams: the hidden tradition'. Art Journal, 9, National Gallery of Victoria, 1978, pp 68-73.

- Drawing on Aaron Scharf's pioneer text Art and photography (Allen Lane, London, 1968) Virginia Spate (1978, p 104) proposes a direct influence in portraits of Roberts' photographic range of skin tone and texture and the popular photo studio portrait style of brightly lit heads against dark backgrounds (which is also known as 'Rembrandt lighting'). W.G. Gaskins advances the view that Roberts' landscape paintings employed camera vision in the form of a differential focus between one plane and another, but this would appear a generic affect of the impressionist era as Roberts had no experience with landscape photography, 'On the relationship between photography and painting in Australia, 1839-1900', PhD thesis, Murdoch University, 1991, pp 360-80.

> return to papers

|