See the woman with the red dress on ... and on ... and on

Gael Newton

Originally published Art and Asia Pacific

Vol 1 No 2 1994

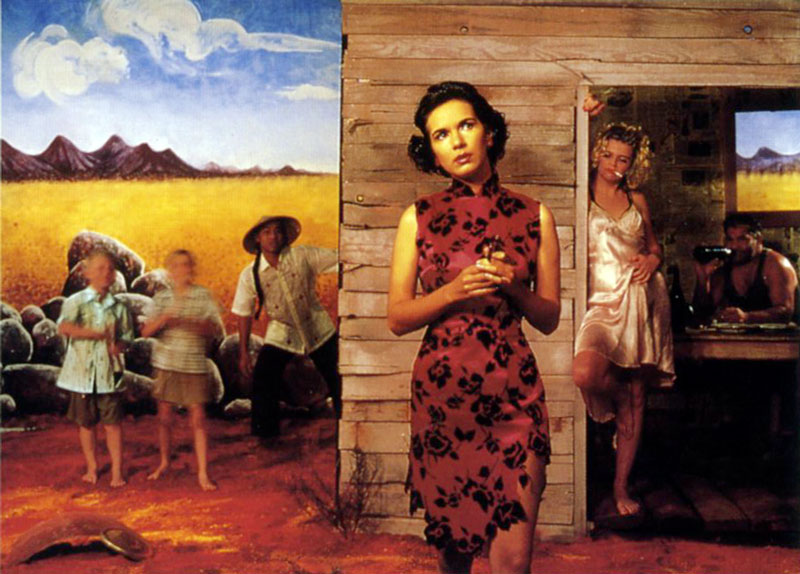

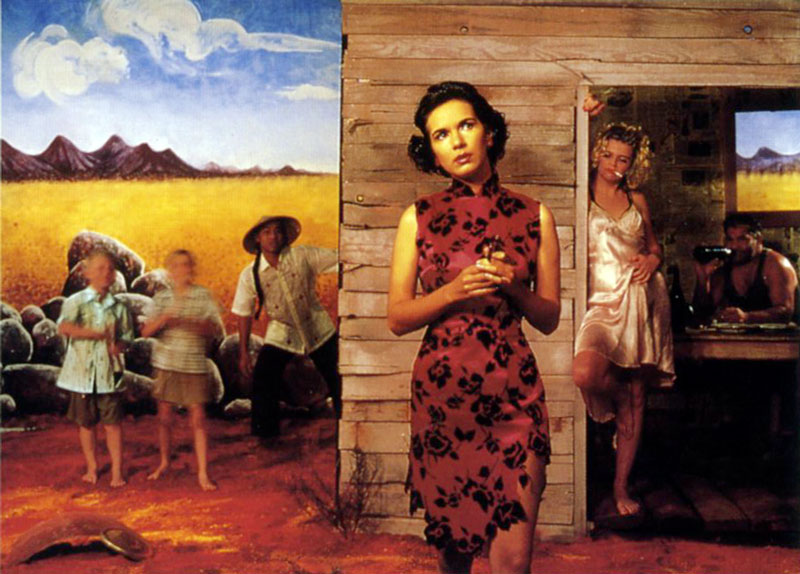

Really ... it's a rhetorical question to ask: who is this fresh and shapely brunette in a cheongsam?

Eyes fixed expectantly on some far horizon she takes a tentative step forward. Her pose is of the Virgin Mary (whose symbol is the rose) but her tattered and seductive dress the colour assigned to the penitent whore, the Magdalen.

Ultimately, it does not matter that our Eurasian heroine is the artist Tracey Moffatt, an Australian of Aboriginal and European background. That satin cheongsam is unequivocally woven out of the storylines of those 'other' stereotypical females of Western cultures; the oriental siren and the sensual native.

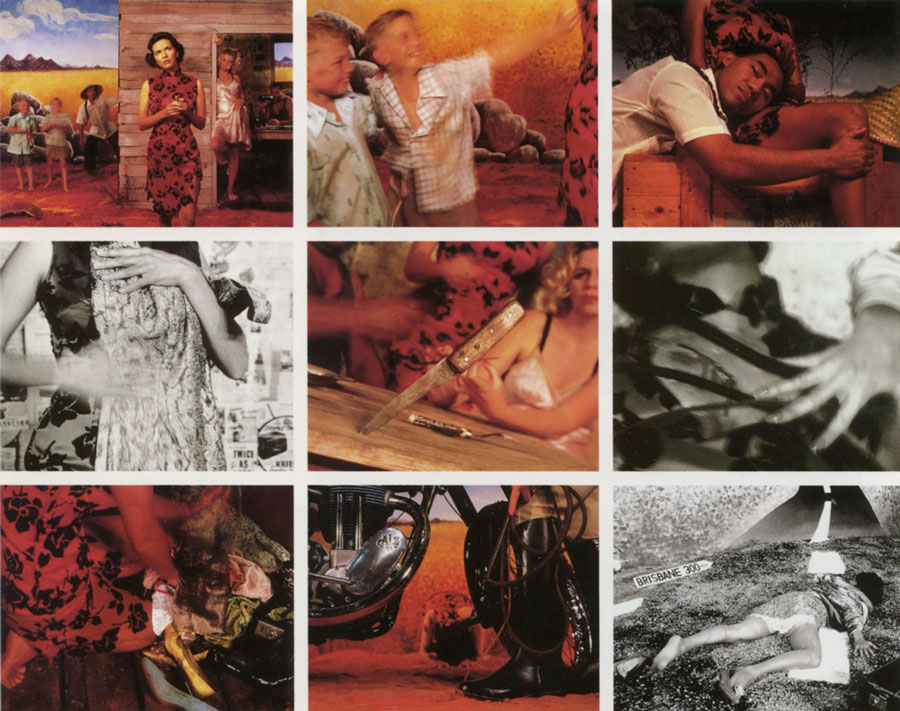

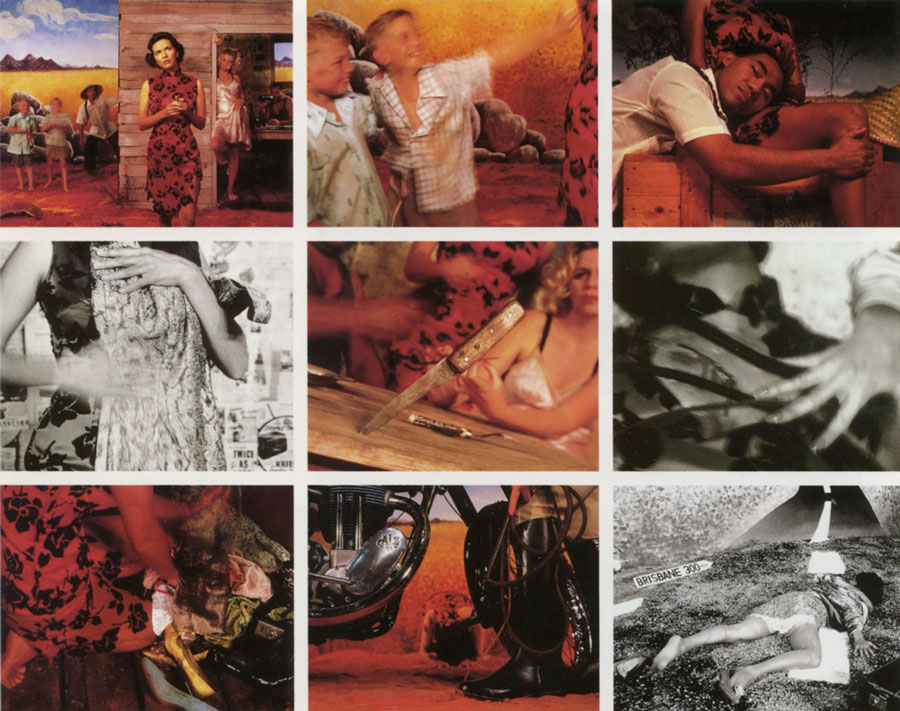

TRACEY MOFFATT, Something More, 1989, series of 9 direct positive colour photographs and gelatin silver photographs,

each 90 x 150 cm framed, National Gallery of Australia.

Aspiration, purpose, wish, hope, desire, INTENTION, goal, good omen, good auspices, promise, good fair, of bright prospect; clear sky; ray of hope, cheer, silver lining; Pandora's box; pie in the sky, castles in the air or in Spain, pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, Utopia, Millennium, hope of Heaven, daydream, airy hopes, fool's paradise, mirage, end resolve zeal.

This composite Woman stands before a lurid stagy set divided in three, like an altarpiece.

The scene could be the Australian Outback, the American Deep South, or some plantation in the Tropics; a backdrop for melodramas about desperate lives in rural hinterlands.

We need no more than this image to know the limited variants upon the theme of the Fallen Woman. She is watched by a motley chorus of differing age, sex, race and class who could easily find their places as characters in B-Grade movies or plays such as the Australian playwright Ray Lawler's 1955 classic The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll about the desiccated hopes of two cane-cutters.

This iconic image is the first frame in Tracey Moffatt's photo tableaux/tabloid Something More, produced in 1989, the year after Australia's Bicentenary, whilst an artist-in-residence at the Albury Regional Art Gallery in rural southern New South Wales.

It was a work which established Moffatt as an artist with something to say, shaped by - yet beyond - her Aboriginality.

The work is also a journeyman's cabinet in the old guild training sense whereby the apprentice shows mastery of the different techniques of the trade.

Following on from the opening long-shot, the remaining eight frames in series are close-ups in which the Woman appears faceless, her clothing serving as signifiers for her changing fate and final death as she strives to escape to Brisbane (The Big City).

The tableau is not a cartoon with simple causes and effects but appears disconnected like stills from some lost movie which, from the clothing, might be from the 1950s. Just as the central female lead overlays many, contradictory images, the individual images of the series are compressed versions of the cultural whole.

As few collectors can afford such large works, Something More appears at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, as a series of six and at the National Gallery, Canberra, in full in varying formats.

Elsewhere individual images have to suffice as trailers for the whole. Sequential imagery is inherent to photography and provides curators with anxieties as to the effect on the series of such cutting to suit different museum requirements.

The work can be arranged as a lineal sequence or as a massive block of triads in which strong diagonal blurs and sweeps create an overall dynamic in contrast to the posed figures and static sets. In this layout the work is a paradigm of the televisual: blip! we change channels but the stories are all the same.

It is only an illusion that the narrative moves forward since it is cyclical and predetermined. As in myth, all versions of this story are true and viewers become a passive Greek chorus merely witnessing the fates of the characters with varying degrees of sympathy.

The real never-ending story is of lives strait-jacketed by prior categorisation. Racial origin and gender, two narratives in Moffatt's chosen media, photography and film, are also relegated to the peripheries of high caste art.

But why should a modern woman artist of the 1990s revive such folktales of the Fallen Woman/country girl lusting for the city?

At the time of production Moffatt's own career was that of an emerging artist but one categorised as Aboriginal and seen thus as confined to the high moral ground of redressing past and present injustice.

Moffatt's personal uncertainty as to her future and hopes for assessment as more than an Aboriginal artist and filmmaker suggest an autobiographical base to the series.

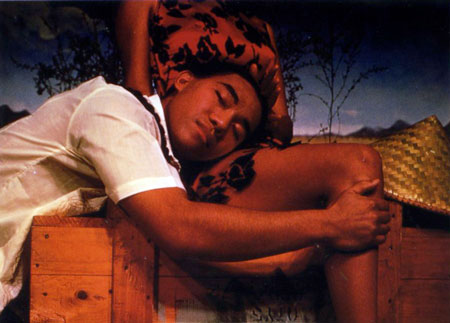

TRACEY MOFFATT, Untitled, from Something More, 1989, cibachrome print framed, 90 x 150 cm.

Something More as a script denies even the potential for success and self-determination on the part of women in general. The fate of the heroine/victim would seem to counter great gains on the feminist front over the past twenty years. Moffatt's own experience as part of a generation of 1980s graduates from Australian art schools has depended on the introduction of courses in photography and film as serious disciplines.

Why should the heroine be defeated in her quest for something more when the present should appear relatively optimistic for women?

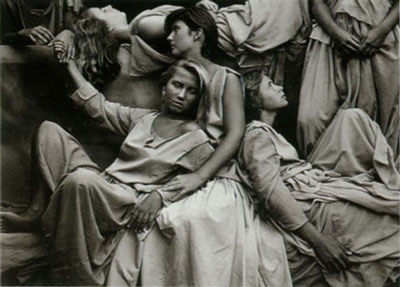

In this paradox Something More presents as many conundrums as an earlier work by Anne Ferran, the enigmatic Scenes on the Death of Nature of 1986.

This five-part photo-tableau has been seen as a landmark work for the arrival of a 1980s post-modern and post-feminist uncertainty and ambiguity, as well as a reinvestment of the power of the

ANNE FERRAN, Scenes on the Death of Nature 1 & 11, 1986, (diptych) gelatin silver photographs, 122.3 x 162.2 cm, 122.3 x 143.9 cm, National Gallery of Australia

Western figurative narrative. The Scenes (the very title with its theatrical and cinematic reference acts as a warning that the issues are from the present) present cool and melancholy arrangements of young girls in crudely fashioned Greek chitons which appear as enactments from fragments of a lost classical bas-relief for which we can never know the full story.

Spell-bound by the neoclassical beauty of the Scenes, few pondered why a modern woman artist of the 1980s should seek to animate a tradition which could cast Liberty and Justice in feminine form but not share political or legal power with her sex.

The film critic and writer Adrian Martin saw beyond the simple reading of Scenes as nostalgia for a unity with the past, noting:

One of the key attributes of the tableau vivant is the way it literally crosses media within whichever particular medium it comes to actualise itself. It is an impure form, and what makes it tremble is precisely its status of being not wholly anyone but simultaneously all of the following: theatre, moving image, still image, fiction.

(Adrian Martin, Scenes on the Death of Nature, Photofile, Summer l986, Vol.4, No.3, pp.11-15. )

Moffatt's tableau format similarly overrides the one-dimensional.

It is curious to speculate on the way in which tableau vivants by women artists have been assigned roles as icons for contemporary photography of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s: Ferran for the 1980s, Moffatt for the 1990s and Carol Jerrems's Vale Street, 1975, for the initial decade of the 1970s photo-boom.

Had these images been made by men it seems unlikely they would have escaped feminist critique as perpetuating rather than subverting stereotypes. With Adrian Martin's comments in mind the choice of a format which 'crosses borders' becomes highly significant for both Ferran and Moffatt. Each moves toward a recognition of a multi-dimensional cultural position.

If Moffatt's tale draws on our familiarity and ongoing attraction to such lurid stories and simultaneously uses format to slip out from the predictability of her sources, might it be presenting more than a parody or heresy? Might she also dare to send herself up?

That wit and irreverence are also strengths of Moffatt's work can be proposed by looking at the role audial memory has in her work. By this I mean the soundscape which is part of all her works to date in their incorporation of the recent folk memory of pop songs and the associations of their lyrics. These audial memories are as iconic a language in their own right as popular visual imagery.

The text accompanying Something More is an obviously invented 'dictionary' style listing of definitions of aspiration, but the title itself in conjunction with the images brings into the work a third dimension: that of sound.

Do we not also hear the opening score lines for a movie, country and western ballads or pop songs such as 'See the Woman with the Red Dress on' and 'Dream on Black Girl'?

In Frame 2, archetypal Aussie kids from the tradition of the cartoons of the irreverent schoolboy Ginger Meggs, movies such as Smiley on which several generations of pre-modern white Australians were raised, and contemporary cereal advertisements, step out of their cute-kids role to mock the woman's aspirations to glamour and future.

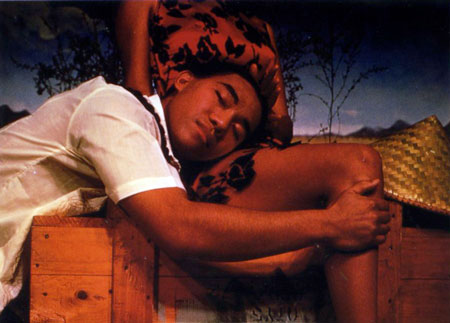

The next image rocks back and forward in time between such moralising story pictures of the nineteenth century as Holman Hunt's The Awakening Conscience, 1853, as well as a stream of B-Grade movies of the 'country girl leaves faithful/ordained boyfriend for the wilds' kind (a theme also found in Charles Chauvel's 1955 feature film Jedda, a film about an Aboriginal girl, the starting point of Moffatt's short film Night Cries, 1992).

TRACEY MOFFATT, Untitled, from Something More, 1989, cibachrome print framed, 90 x 150 cm.

What role does the passive older woman in the Jean Harlow peroxide hair and satin dress play? Is she the has-been-there-before who has failed to escape? Is this the parable of the older woman artist, or the gender and race issue?

Does the working-over of situations more appropriate to their mothers' generation than their own career-dominated lives cause younger women to try to expiate that guilt of modern feminists that the tragedies of the past are not their experience?

A note of sexual violence also appears in the black and white image of the heroine with her neck exposed (preceded by a canon of images of the exposed jugular in horror movies and the work of surrealists such as the photographer Man Ray), as well as the misogyny paraded as pop art in the work of the 1960s British sculptor Alan Jones, or more recently the fashion photographs of Helmut Newton and Lord Lichfield's up-market girlie calendars for the Pirelli tyre corporation.

However, in the image which depicts subjugation to Bikie machismo we note the whip is held by a female. The Fall comes in the last triad in which, following on from a trying-on of the clothes of the white mistress (?), there is a theft - then the Fall in the most literal and figurative sense.

Its melodrama suggests and distances the work from the passivity of the work of a heroine of contemporary women photographers, the American artist Cindy Sherman, widely known for her use of the genre of film stills in her own work.

Throughout the series men are relegated to the background, an inversion of the usual representation of men as the oppressors of women, whether white or black.

Has the artist experienced the power of the social control of women by other women as being as powerful as that of males and authoritarian structures?

Something More is more than a 1950s costume drama. Clothing is indeed the protagonist of action and possesses greater signifying power than the individual faces, which are distanced often by focus or blurred action.

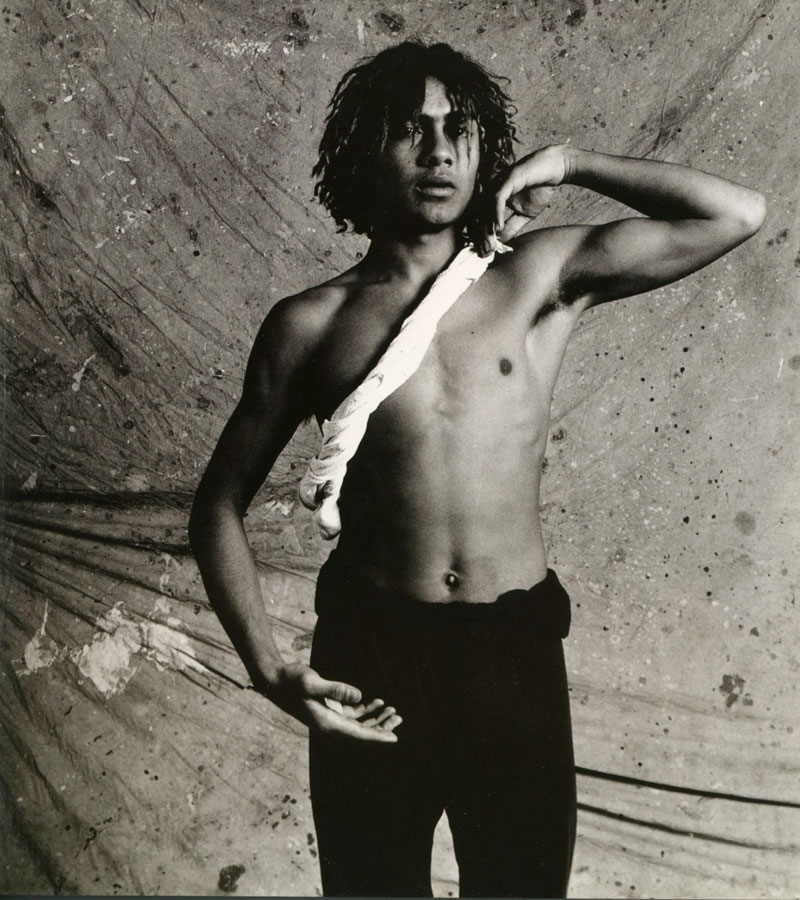

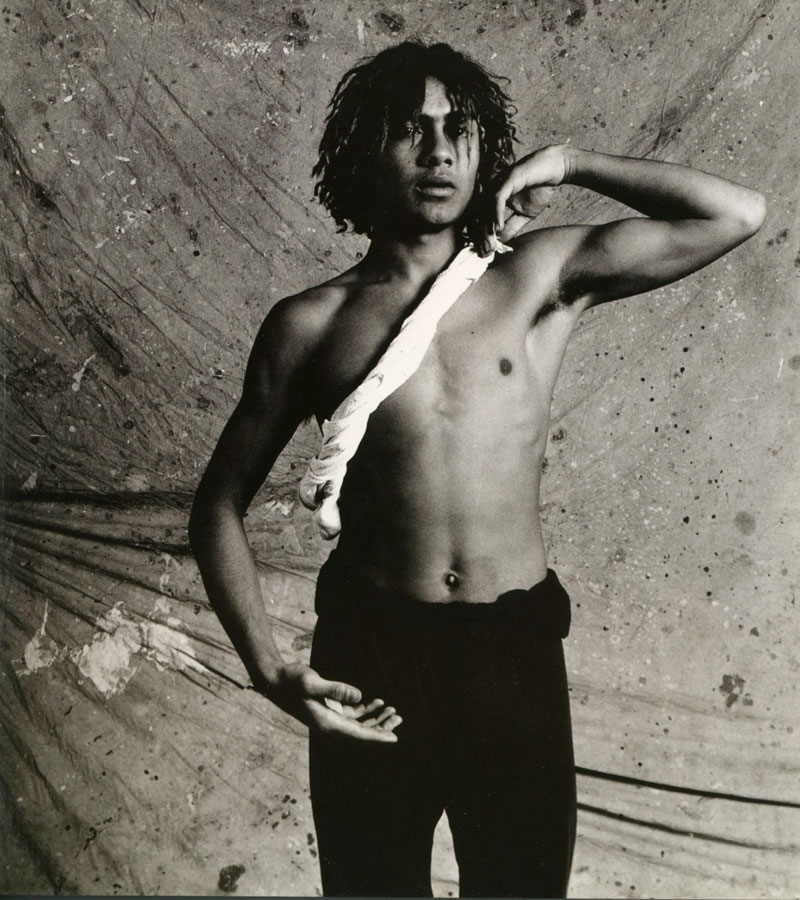

In looking back to an earlier series by Moffatt called Some Lads, 1986, in which Aboriginal dancers are presented without accessories such as artefacts or body paint, Moffatt has surely understood that dress and undress is one of the most powerful issues around which the colonial European attitude to the native turns.

TRACEY MOFFATT, Some Lads II, 1986, gelatin silver photograph, 45.7 x 45.7 cm, National Gallery of Australia.

From the missionary who sees salvation in shoes, it is by undress that we demark the civilised from the primitive, and ritual from righteousness.

Whilst clothing is urged upon the native, to overstep and dress in white finery is to transgress an assumption that the native will never aspire to the masters shoes.

In speaking of the first public body of work to establish her name, Moffatt sought to distance the work from the posed tableau of nineteenth-century photographers of Aborigines such as J.W. Lindt and the naturalism of twentieth-century documentary photography which is obsessed with showing Aborigines in their 'natural' bush environment rather than their modern lives in which they also, like white Australians, watch TV, listen to rock music and dress fashionably.

Moffatt's use of overt artifice distances the imagery from traditions in still photography not only of the naturalist/ documentary kind but also from the often unsuccessful attempts by photographers in the past to rival the fine arts by elaborate attempts to create believable 'natural' allegories.

The generation of artist-photographers to which Moffatt belongs, i.e. those born in the mid-1950s to early 1960s, distance themselves with scale and colour work from the modest monochrome and 'thoughtful' genre of documentary. Something More is a work which combines great visual pizzaz of surface with a suggested rich third dimension of sounds.

In performing such a dazzling visual medley, in 'working the crowd' so well, Moffatt sails close to being too clever and puts at risk the intellectual subtlety which is also present.

Later photo-series such as Pet Chang, 1992, and her film Night Cries, present emotional depths and risks.

In Moffatt's work, naturalism is inverted in recognition of the unreliable witness the camera has been as regards truth. Ironically, it is the power of artifice which has made photography one of the most dynamic of contemporary arts in Australia.

References

Geoffrey Batchen and Tracey Moffatt, 'NADOC '86 Exhibition of Aboriginal and Islander Photographers', Photofile, Summer 1986 Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 24-6. Catherine De Lorenzo, 'Delayed exposure: contemporary Aboriginal photography', ART'and Australia, Spring 1993, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 57-62.

Sylvia Kleinart, 'Mobilising the Margins', Photofile, Winter 1988, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 11-14.

Terence Maloon, From the Empire's End: Nine Australian Photographers, Circolo de Bellas Artes/University of New South Wales, College of Fine Arts, Sydney, 1993.

Gael Newton AM was Senior Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

more about Tracey Moffatt

more essays by Gael Newton AM

|