Behind the glass:

the story of Olive Cotton's classic Max after surfing, 1937

Gael Newton

Originally published in antiques & art, New South Wales, May–September 2007

In late 1937 photographer Olive Cotton had been working for three years in the Sydney studio of her childhood friend Max Dupain.

Cotton, who had been taking photographs since 1922, had met Dupain–the son of family friends–in 1924 and joined the NSW Photographic Society in 1929 to develop her art photography while studying for a BA at Sydney University. She graduated in 1934 with majors in English and mathematics but soon joined Dupain's newly opened business as a general assistant.

It is hard to imagine the pay was in any way comparable with other graduate positions. By 1937, the Dupain studio was doing well in all aspects of commercial advertising, illustration and social portraiture and Dupain also had a profile as the face of modem art photography through the pages of both Art in Australia and The Home magazines. Cotton's gentle descriptions of her six years working in the Dupain's studio in later life however paint a clear picture of her role as 'dogs-body'.1

She remained an assistant after their marriage in 1939 and until after their split in 1941. There was no doubt as to her ability; Cotton was invited back to run the studio as a full professional from 1942-45 during Dupain's war service. The business had been taken over by Hartland and Hyde engravers and the Dupain studio relocated to the firm's premises in Clarence Street in 1942.

Cotton later described her years as a professional managing the Dupain studio as her 'great years' but by 1935 she had evolved a distinct style in which the dark tones, suffused highlights of the earlier style of impressionistic art photography supported and alternated with the bolder lighting, geometric forms and unusual angles of modernism or the mysterious conjunctions of surrealism. She was clearly a skilled and mature artist who had been exhibiting her photographs in local salons since 1932 and international salons from 1935. |

|

|

|

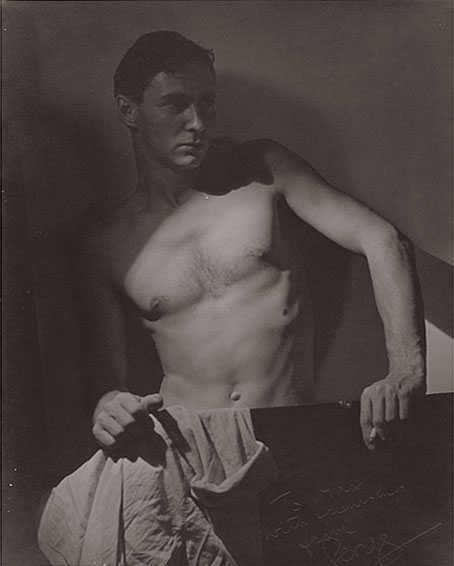

Olive Cotton (Australia 1911 -2003), Max after surfing, 1937 or earlier, gelatin silver photograph, printed 1937. National Gallery of Austraiia |

She had made a number of works now considered classics such as the 1935 Teacup ballet and the in-your-face close-up of Shasta daisies of 1937 which were both hung in the London Salon of Photography exhibitions in their respective years of making. In the next year Cotton exhibited her work in the massive 1938 Sesquicentenary exhibition in Sydney and alongside Dupain as the only woman in the following invitation-only and self-consciously progressive Contemporary Camera Groupe exhibition in David Jones Gallery.

In the spaces between work duties Cotton continued with her own experimental works, sometimes using the studio equipment - or from 1937 her own new Rolleiflex. She was not the only assistant; in 1937 Dupain took on Geoffrey Powell, a personable and handsome young man who, since mid-1936, had been working as an assistant at their only main business rival, the American-style advertising studio of Russell Roberts. Powell was arguably less qualified than Cotton. It was a lively time and Cotton made a portrait in the studio of her two young and very boyish looking associates fooling round with a big sun hat used in a fashion shoot.2

|

|

|

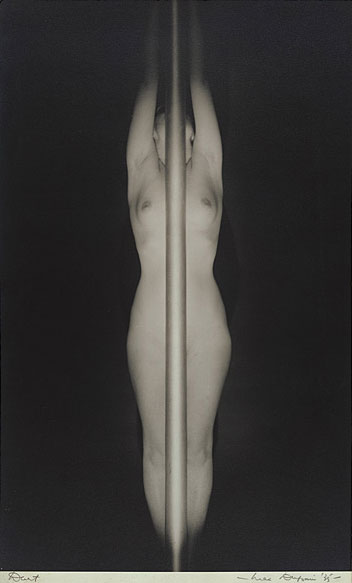

Max Dupain (Australia 1911 -1922), Dart, 1935,

gelatin silver photograph.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

Olive Cotton (Australia 1911 -2003), Shasta daisies, 1937, gelatin silver photograph.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

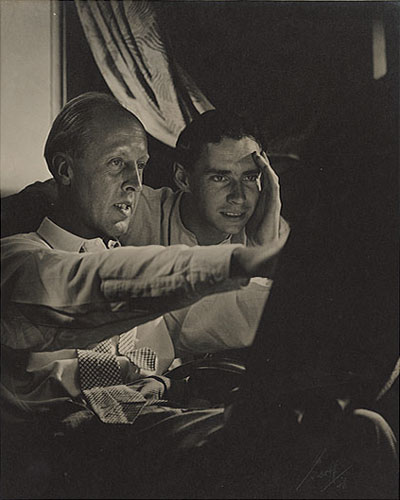

Geoffrey Powell, (Australia 1918-1989), The discussion, 1937, George Hoyningen-Huene and Max Dupain Sydney, 1937, gelatin silver photograph.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

One fascinating and important image from these years is Cotton's figure study Max after surfing showing a bare-chested Dupain with cigarette in hand and shirt slung over a panel covering his lower half. The pose is that of the seductive gigolo rather than a surfer or nature lover and even has faint echoes of the images of Nijinsky in his Greek faun role from the Russian Ballet.

The style is overtly within the orbit of 1930s Hollywood-style portraiture and fashion studies, but the image itself is complex, compelling and strange. Attention first falls on the Dupafn's spot-lit twisted torso and bent arm and then is drawn into the face in deep shadow, a crumpled shirt or cloth, shadows and angles compete for attention in the foreground. The pose does not look all that comfortable and Dupain's closed fist on the left of the image has a disembodied character while his profile casts an eerie 'face' upon his shoulder.

Cotton made a number of figure studies and portraits of Dupain over the years, though none quite like Max after surfing. Her interest in spontaneity and a more animated light favoured outdoor images. The image, later titled Max after surfing, somewhat turned the tables on Dupain by making him the subject of a study which, while not nude in the strict sense, has a seductive and sensual aura. Curator Helen Ennis, author of the major studies on Cotton, commenting that, 'The play between light and shade, and between what is visible and what is not, creates a space for erotic imaginings that has no rival in the work of her peers'.3

In 1934 Dupain had been the first Australian photographer to make an important body of nude studies - his work inspired by a cross between Lionel Lindsay's celebration of the body and Man Ray's surrealist works.

|

|

|

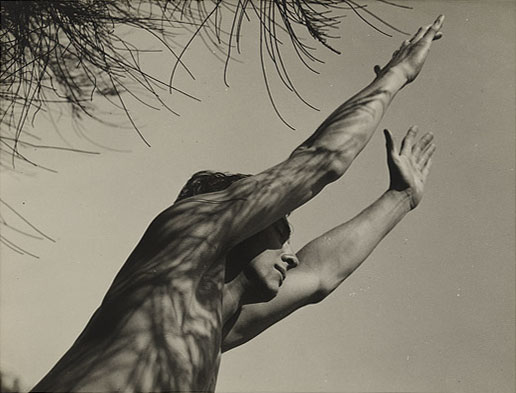

Olive Cotton (Australia 1911 -2003), Max in shadows, 1935, gelatin silver photograph,

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

|

George Hoyningen-Huene (Russia/USA 1900-1986),

David Jones fashion model, 1937, gelatin silver photograph.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

Max Dupain in turn used Cotton as a model for at least one nude study of 1939. Quite when (heir teenage friendship became passionate is not clear, but there is little to suggest they were that close from the beginning of their working relationship but possibly were a couple by late 1937. In her elegant, sensual but also moody image of Dupain, Cotton seemingly condenses the beautiful young man's physique with his own modernist photographic aesthetic - inspired in turn by his vision of classical Greece and a Platonic quest for perfect geometric forms in dynamic tension. What carries the image however, is not the physical world, as she pointed out later in life, 'I think the way light falls is the thing that brings a photograph to lite, where it falls is the sort of accent and I think it's the most important thing.'4

Cotton and Dupain married in 1939 but separated in 1941 and they divorced in 1944. In 1943 however, Cotton was invited to return to manage the studio for owners Hartland & Hyde while Dupain was on war service. Cotton married Ross Mclnerney in 1945 and moved with him to a property in rural New South Wales after the war. While continuing with her photography, Cotton did not do much commercial work until the 1960s when she opened a portrait studio in Cowra.

Cotton never ceased being a photographer but had little national profile in the 1950s-60s. She was, however, in the public eye again following the boom in interest in historical art photography throughout the 1980s and the reclamation projects following International Women's Year in 1982. The image since then has occasioned commentary about its sensuality and even some championing for its pioneering role as a male nude by a woman photographer. Isobel Crombie, Senior Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria, notes Cotton's emphasis 'on (Dupain's) muscular, lean body is more than an erotic portrait: it also reflects Dupain's strongly held belief that modem men should model their bodies on those of Greek and Roman statuary.'5

While Olive Cotton retained a print of Max after surfing now held by the family, she did not include the negative of the Dupain study with those she took her when she left the studio. Some years after Dupain's death in 1992, Jill White manager of the Max Dupain exhibition negative archive, returned the negative to her. Cotton had some reservations about reprinting the image but the modem prints under a newly applied title Max after surfing and dated 1939, proved an instant success.

From the time of its inclusion in the 1995 National Library monograph on Cotton's work Max after surfing has attracted attention and celebration. Dupain also held a print which is now held by the National Gallery of Australia and his print is inscribed To Max with friendship from George, the autograph being that of Russian bom aristocrat Baron George Hoyningen-Huene the world famous glamorous chief photographer for French Vogue and the American publication, Harpers Bazaar.

George Hoyningen-Huene (1900-1968) had revolutionised fashion photography in the 1930s making a number of sensual shots of swimwear and figure studies inspired by classical Greek statuary. He was in Sydney for five days only between 5 and 10 December 1937 having arrived into Brisbane on 3 December aboard the Dutch ship Nieuw Holland which serviced a route between Malaya, Singapore, Java then Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney. He departed for San Francisco on 10 December on the Matson line Monterey. Hoyningen-Huene was, it seems, simply on a cruise which he would have joined in one of the Asian ports.

Learning of his presence in Sydney the alert fashion editor at David Jones department store quickly commissioned the Baron to do a fashion assignment and a print of a model in a new toque hat were published in The Home magazine of 3 January 1938.

Max Dupain similarly eagerly sought out Hoyningen-Huene and invited him to the studio where assistant Geoffrey Powell made a portrait titled The Discussion of the older man and the adoring Dupain looking at a print. Two prints of Powell's portrait - both acquired from the photographer - are held by the National Gallery, one undated the other signed Geoff 38 but this date must signify a print date and was possibly a late addition to the print.

It is not surprising that Dupain and Hoyningen-Huene genuinely appear to have got on well enough for the visitor to autograph Dupain's personal print of Cotton's Max after surfing. Dupain was maldng sophisticated modernist fashion and figure studies akin to those pioneered by Hoyningen-Huene and they shared an interest in the classical aesthetic as a basis of modernism and body culture. Dupain was athletic; his father ran a modem physical culture institute in Sydney and Hoyingen-Huene was expert in the Pilates system.

He was also homosexual and noted for his own studies of the male body. It would seem the three young Sydney photographers found their elegant and urbane visitor a charming and willing subject and being photographers they had fun making pictures.

The inscription from Hoyningen-Huene on Cotton's print confirms the date of Max after surfing must be 1937 as it is unlikely indeed that a print would have been sent on to him later and then posted back. The work dated to 1937 rather than 1939 makes it a companion to Dupain's now famous Sunhaker image of that year. (Whether that work was made in early or late summer of 1937 is not known.) Sunbaker was reproduced only once in 1948 (as a variant image with fingers closed) then not exhibited or reproduced until 1975.

The National Gallery is fortunate to hold vintage prints of Cotton's 1937 portrait Max after surfing as well as several earlier outdoor portraits of Dupain, the portrait of Dupain and Hoyningen-Huene by Geoffrey Powell and Hoyningen-Huene's fashion study for David Jones, Dupain's portrait of Hoyningen-Huene as well as works by Hoyningnen-Huene. It is a testament to the unique strengths of the collection nationally and within the Asia-Pacific region.

| |

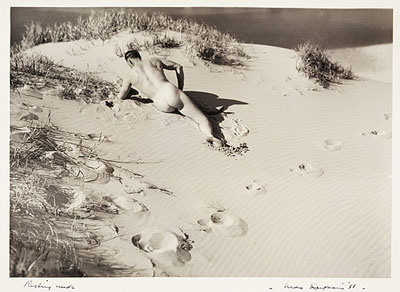

Max Dupain, Resting nude, 1931, gelatin silver photograph.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

|

Notes

- Olive Cotton cited in Helen Ennis, Olive Cotton photographer Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995, p. 5 and n. 18, p. 70.

- See National Library of Australia: http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-anl2799855

- Helen Ennis, Olive Cotton, [exhibition catalogue] Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2000, p. 16.

- Olive Cotton cited in Helen Ennis, Olive Cotton photographer Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995, p. 5 and n. 18, p. 70.

- Isobel Crombie interviewed by Karen Heinrich, 'Alter image', The Age, 30 May 2002.

Gael Newton

more Essays and Articles

|