|

Special pages on John Kauffmann - click here

John Kauffmann

Art Photographer, 1864 - 1942

Gael Newton AM

This essay was originally published in 1980

in

The Australasian Antique Collector

This May 2021 version has minor amendments

|

|

|

A little over one hundred years after the introduction of photography into Australia, Jack Cato published the first history of its development. In The Story Of The Camera in Australia, Cato credits John Kauffmann with being the pioneer of pictorial photography.

As "pictorialism" was the name of the first movement in photography to define and establish the medium as an art, Kauffmann became the progenitor of all creative photographers in Australia. Cato was a photographer by profession but had a novelist's touch when it came to describing the characters in his "story".

Perhaps because he was also a pictorialist, Cato's pen portrait of Kauffmann is one of the most vivid in the book. Indeed, the greatest contribution of Cato's history may not be the facts, which tend to be available in permanent records anyway, but his ability to convey the essential personalities of our past photographers:

"He was never quite one of us, those years in Europe having left him a confirmed Continental. He was 6ft 3in tall, very dignified and quiet, and seriously preoccupied with his thoughts. I knew him for thirty years, saw him almost every week, yet never knew him to smile. He was one of the best-dressed men in Melbourne; one would always note his distinguished 'Red Indian' profile as he strolled 'The Block' complete with yellow gloves, cane, spats and his pince-nez on a silk cord. He was usually off to an art exhibition, a chamber music recital, or an alfresco lunch in the Botanical Gardens, where he could find again something of the spirit of the Vienna Woods."

Jack Cato, 1889-1971, The Story Of The Camera In Australia, 1955, p. 149

As suggested by Cato's description, John Kauffmann remained aloof from the photographic fraternity. Kauffmann did not seek office in any society over his long career, nor did he write articles or give lectures. Unfortunately, we do not have a photograph of Kauffmann in his yellow gloves; we do not even have one letter — only a few short secondhand reports of his opinions on photography.

The chief source of biographical information on Kauffmann is the critical essay by Leslie H. Beer (an artist and one time editor of Harrington s Photographic Journal), in The Art Of John Kauffmann, published in 1919. The publication was limited to 500 copies and contained twenty half-tone illustrations of Kauffmann's work as well as the lengthy essay and commentaries on each picture by Beer. It may well be the first real monograph on an Australian photographer — a rare event even today.

Cato's short account in the Story was based on the monograph, and information from Harold Cazneaux (1878-1953), Australia's outstanding pictorialist. Cato and Cazneaux credit Kauffmann with being the first exponent of pic-torialism, responsible for the subsequent development of the style, which was a dominant trend between 1905-25. Cato makes strong claims for Kauffmann's impact on the South Australian Photographic Society, which he had joined in July 1897 on his return to Adelaide after ten years in Europe studying photography:

"His inspiration spurred them to such efforts that in 1898 they held an exhibition which launched Pictorialism in this country, raised the whole standard of photography here to a new level, and influenced all the future camera workers of Australia." Cato, op. cit., p. 149

A discussion of pictorialism can (and has) filled several books. All reputable histories contain a chapter on its emergence in the late 1880s in England.

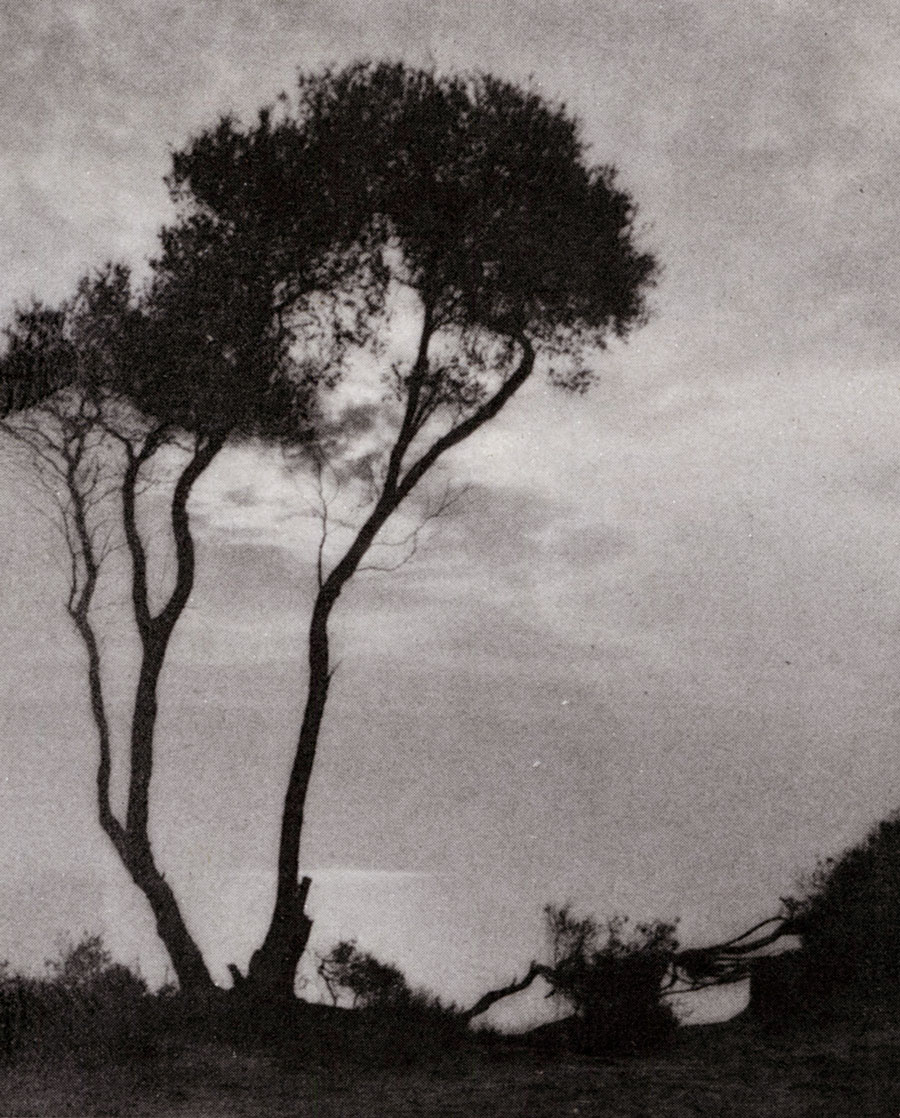

The style was romantic in its theories, especially of landscape, and dependent on Whistler's style and theory of impressionism which scorned prosaic realities and the detail beloved of the Victorian era. In order to gain breadth and control over chiaroscuro, the pictorialists adopted various processes which suppressed detail and altered the tonal scale.

The extremes to which the pictorialists went to render their photographs painterly were discredited from around 1920 onwards as a great betrayal of the inherently realistic detail of the camera. It is only recently that the pictorial era has been recognized again — if only for its important role in promoting photography as an art.

John Kauffmann was the son of Alexander, a prominent importer with premises in Grenfell Street, who had arrived in the colony around 1854. John was the second son. Louis, the eldest, who had been taken into the business in 1883, had moved to Melbourne by 1894 to set up an importing firm. There were two sisters, Caroline and Julia.

Whether John worked in the family business is not known. Perhaps his apprenticeship as a clerk with Adelaide architect, Harry Grainger, prior to going overseas, reflected an early bent towards the artistic rather than the commercial.

|

A Continental Landscape, typical of early work by Kauffmann exhibited on his return to Australia.

It is a later print, softer in focus than those shown in the 1980s. |

Once overseas, Kauffmann became one of the many converts to the new art photography. He arrived in England around 1887 to gain further experience in the office of Messrs Macmurdo and Home but abandoned this work to study photographic chemistry. It has not been possible to verify any of the details in Leslie Beer's biography concerning Kauffmann's years in Europe. Kauffmann went to Switzerland, Bavaria, Munich, Paris and Vienna, studying photographic processes and the new reproduction processes such as photogravure.

After ten years he returned to Adelaide in 1897 and is listed in The Australasian Photo Review as a member of the South Australian Photographic Society by July. During the 1890s many pictorialist societies were formed and influential exhibitions of the new style held under their auspices.

Kauffmann would have been able to see many of the pioneering salons of the Vienna Camera Club. It is fairly certain that he was not a member of The Linked Ring in England and that he did not exhibit at the Royal Photographic Society or the "Links" Photographic Salon before his return.

Kauffmann may well have won prizes at European competitions or those run by The Amateur Photographer, which was the main journal of the new movement. The most important point is that Kauffmann was in Europe in the years in which pictorial photography was being formulated. It was in those same years that Alfred Stieglitz, who had similarly gone to study science in Europe, abandoned his studies to embrace the new art form.

Kauffmann quickly established a reputation on his return for new and original work through exhibition of his photographs. He did not set up a professional studio in Adelaide, and is not even listed until 1905 in the directory, and then only as a private citizen, not a photographer. Electoral rolls of this period list his occupation as a clerk.

The earliest recognition of Kauffmann's work appeared in The Australian Star, a Sydney paper, on October 8, 1897, on page 2:

"Some of the most perfect photographic work ever seen has been submitted to the Society of Artists for exhibition if approved at the Society's show".

The reviewer referred to Kauffmann as having secured medals overseas and enthusiastically described the ". . . delicate tones and tints . . ." of the Continental landscapes as ". . . clear and truly artistic".

|

A Winer Sunset. This print shows Kauffmann's style before 1900.

From the 1902 Catalogue of the South Australian Photographic Society (State Library of SA). |

The photographs were enlargements on bromide paper, a process which was in vogue in the 1890s, earlier processes being limited by the size of the negative. Bromide paper was popular with pictorialists as it gave a softer image on a matt surface, instead of the brilliant detail of albumen papers.

Kauffmann's enlargements were shown at the Baker & Rouse photographic suppliers warehouse, and had been made in Melbourne by Austral Co., the importers of the paper. The Society of Artists exhibition did not include any photographs in the 1897 exhibition, though graphic arts were admitted for the first time.

A notice in The Australasian Photo Review of January 1898 refers to the enlargements on "pearl bromide" paper being later shown at the head office of Baker & Rouse in Adelaide. On that occasion, The South Australian Register newspaper described them as "exquisite in the delicacy and gradation of the tones, giving a depth and softness singularly attractive to the eye of the lover of artistic effect".

As if to distinguish the images from ordinary photographs, they were described as "alluring landscape, water, and cloud interpretations of Nature" (The Register, Feb. 11, 1898).

Reviewers of the annual exhibitions of the South Australian and New South Wales Photographic Societies in The Australasian Photo Review and Australian Photographic Journal (later known as Harrington's Photographic Journal) noted Kauffmann's pleasing landscapes, especially the fine atmospheric effects. The following year Kauffmann won 1st and 3rd prizes in the landscape class of the Photographic Society of NSW Inter-Colonial Exhibition in October.

|

| Untitled, c 1910-1920. Art Gallery of New South Wales |

By 1901, Kauffmann's standing with his own society was such that he was invited to be a judge, along with H. P. Gill, at the annual exhibition, and to display a selection of his photographs in the invitation section. Harry Gill was director of the School of Design, Painting and Technical Arts, located in the Exhibition Building. Here the Society held its meetings until 1900.

Gill had been a member since 1894, and was well known as an art teacher. Kauffmann also attended art classes at the School of Design, possibly prior to his departure overseas. A similar invitation was extended to Kauffmann for the 1902 annual exhibition.

The 1901 exhibition had been considered "one of the finest" ever seen in Adelaide and "proof of the camera's recent advances" when reviewed by The Register of October 19, 1901. Some of the works, it was said, could be mistaken for works of art. The implied reason was the absence of "all the sharp and hard lines usually associated with photography".

Perhaps it was only Kauffmann's exhibits that qualified for such praise for their impressionistic qualities. If artistic photography in this vein was the highlight of the exhibition, it is likely that it was due to Kauffmann's influence over the last four years.

The success of the 1901 exhibition, which was open to interstate entries, encouraged the SA Photographic Society to embark on an international salon for their next annual show. This 1902 exhibition was duly held in September in the rooms of the Society of Arts in the Institute building, North Terrace, where the SAPS now held its meetings. The "international" content consisted of eight gum-bichromates by David Blount of Scotland and lantern slides by Harold Hill of Sheffield. Blount won a gold medal for his gum-bichromate photograph "The Daughter of Eve" and a silver for "The Mountain Tarn".

Gum-bichromate was one of the control processes in pictorialism which were popular between 1890 to 1910. It was felt to be very expressive, as the photographer could even create brush marks.

Kauffmann had left Europe before the pigment control processes became popular and seems never to have worked in gum or bromoil, preferring carbon and bromide prints. At this 1902 exhibition, Kauffmann exhibited 14 carbon prints described as "exquisite" by the Adelaide Observer of Sept. 27, indicating "a keen sympathy with nature", the "cloud effects being particularly well wrought" (p14).

The SA Photographic Society held another International Salon in 1903. The international section was expanded in quantity to include at least 50 lantern slides from a camera club in South Africa, and an entry from Calcutta!

Blount and Hill exhibited again. There are references to' a print by Horsley Hinton and one by H. P. Robinson.

However, the SAPS exhibition was completely outdone by the Photographic Society of NSW International Salon held in December, which included gum-bichromates by Edward Steichen in the non-competitive section, as well as by Blount, who received the award of honour for one entitled "The Kitten".

Horsley Hinton appears to have loaned one print, as well. There were 500 exhibits, the majority of which were presumably by Australians. Kauffmann, who was among the medal winners, drew the attention of Syd Long, who reviewed the exhibition:

"Mr Kauffmann's strong point seems to be the rendering of silvery light on masses of water".

Australasian Photographic Review, Dec. 21, 1903, p. 442, 450.

The size and scope of the NSW Photographic Society exhibition indicate that the Society had well recovered from the depression of the 1890s, when membership had declined. The leadership of the Adelaide society seems to have passed to their Sydney brethren from this point on for by 1905 the SAPS was reported in a decline. The significance of the 1903 Sydney International is revealed in an editorial comment on the show in the Australasian Photo Review:

"We notice many of our old friends from the fuzzy-wuzzy school, baffling the vision and confusing the brain of onlookers".

An impressionist style of art photography had obviously become a popular trend by this time, and a potentially subversive one to some reviewers. Edward Steichen, the star of the newly formed "Photo-Secession" in America, was producing some of the most extremely painterly photographs of the pictorial era with the gum process. It was such examples that were on view in 1903.

|

| Untitled, signed J. Kauffmann, 1907 (private collection) |

| |

|

| From the Sunraysia book, 1920 |

| |

|

| From the Sunraysia book, 1920 |

| |

|

| Collins Street, 1907 (private collection) |

The early enthusiasm for Whistler-inspired artistic photography seems to have threatened by 1902 to go to extremes even worse than the brush marks some photographers added to their gums! In reviewing the 1902 SAPS exhibition, T. Helens of The Adelaide Observer struck a warning note in regard to Blount's exhibits:

"The larger works by which he is represented are of the impressionist order, and while they are not calculated to please all tastes they have a value in their suggestiveness."

However, there was a "good opening for this class of subject within reasonable bounds," provided limits were observed. Blount's "The Last Pale Glimpse of Glimmering Light," in the reviewer's opinion, was beyond the accepted level of abstraction from nature.

|

| The Fairy Wood, c.1910-1920. Art Gallery of New South Wales |

Such sentiments for and against impressionism in photography reflected a general debate on the style which had been going on in Adelaide for some time. In 1898 the purchase of Syd Long's "The Valley" from the first Federal Art Exhibition for the Art Gallery of South Australia had caused quite a controversy. It prompted a defence of impressionism in the editorial of The Register on the grounds that its characteristic soft focus was true to natural vision, as it was not possible for the eye to see everything at one time in sharp focus; the mind in fact received a series of impressions.

The new style would educate the public to an awareness of this truth:

". . . it will impart the hint that much pleasure can be derived from the habit of retaining in the mind the impression conveyed when the beauties of a scene first burst upon the gaze, and before the 'poetry of the indefinite' has been dispelled by the prose of a matter of fact scrutiny of detail". The Register, Nov. 28, 1898, p. 4

Apologists for impressionism also stressed that art was not a mere imitation of nature, but more an interpretation by an individual of feeling. One critic declared that "art is not a photograph, but a man's view of nature" (The Register, Dec. 8, 1898).

With such views supporting a new taste, it is not surprising that photographers would adopt a similar aesthetic.

John Kauffmann arrived back in Adelaide at a propitious moment for the reception of pictorial photography. It is unclear how impressionistic Kauffmann's work was on his return. The press notices consistently refer to his atmospheric effects, mists, clouds and water reflections, and stress his artistry, especially with tonal values.

Unfortunately, no prints from this era have survived and one poor illustration in the 1902 SA Photographic Society catalogue is the only published image yet located. Indeed, until a private collection was located in Melbourne very few prints were known to exist.

Several in his collection show European scenes, but the prints were almost certainly made much later, in the twenties. As the reviewers do not draw particular attention to Kauffmann's focus, it is likely that he did not adopt the very soft-focus which was later a trademark, until after the 1902-3 SAPS exhibitions.

The Photographic Society of NSW International Salons accelerated or popularized this trend generally. Kauffmann, however, was assuredly a pictorialist, though we have no record of his using the term when he arrived in Adelaide in 1898. The instant attention from the press confirms that Kauffmann's style was distinctive if not new.

It is hard to precisely date the first references to pictorialism in Australia or whether Kauffmann was the single originator of the style. Certainly, no earlier examples have been located. Two other pictorialists, F. A. Joyner and Fred Radford, were in Adelaide in the 1890s; the latter even wrote an article on "Impressionist Photography" for The Australasian Photo Review in 1898.

But it is not known if their adoption of pictorialism predates Kauffmann's appearance at the SA Photographic Society. It is fairly certain that Kauffmann did not bring examples of overseas pictorialism with him or inspire the SAPS to hold the reputed national salon in 1898, as is claimed by Cato.

Nor does Cazneaux appear to have actually met Kauffmann in Adelaide. In the letters Cazneaux wrote to Cato in 1951-2, Cazneaux relates that he and Kauffmann were "good and sincere friends" but their friendship would largely have been through correspondence.

Cazneaux first met Kauffmann around 1908 in the Photographic Society of NSW rooms and was able to visit Kauffmann again in Melbourne in 1934 when he was judging the Melbourne Centenary Salon. The lack of early original prints by Kauffmann makes it difficult to assess how closely Cazneaux's early work followed his lead. Cazneaux did not actually begin his photographic career until 1904, when he moved to Sydney to take up a job at Freeman's studio. By that time, Cazneaux would probably have acquainted himself with the work of other pictorialists.

Kauffmann's father died in 1901 and his mother, Therese, in 1907. After 1909 he left Adelaide and moved to Melbourne. Perhaps the death of his parents provided an income, or he may have left to work for his older brother Louis in his importing firm.

It was not until 1915 that Kauffmann appears in the Melbourne directory as a professional photographer. The studio was located in Scourfield Chambers, 163 Collins Street. Kauffmann was listed at that address from 1912 but not as a photographer.

He may have joined the Victorian Amateur Photographic Association which he had exhibited with as early as 1905 at their international salon. By 1910, Kauffmann had estalished his reputation in Melbourne well enough for the Association to mount a "one-man show" of his work at their rooms in Swanston Street.

This appears to be the first time such a privilege was extended by the Association and suggests that Kauffmann was considered the leading pictorialist of the day. J. Temple Stephens, usually listed as an early pictorialist exhibiting since at least 1902, would have been a local candidate for such a show.

Leslie Beer described it as the first "one-man show" in Australia. This is incorrect. Harold Cazneaux had been given a show in 1909 by the Photographic Society of NSW. J.W. Lindt, the master of 19th century topographical tradition, may also have had a "one-man show" in Melbourne in 1909.

Beer, as an ex-editor of Harrington's Photographic Journal, should have known of these shows. Kauffmann may even have been inspired by Cazneaux's show, as he may have heard of his plans during his visit to Sydney in 1908.

|

| The Cloud, c.1905. National Gallery of Victoria |

There were 74 works in the 1910 exhibition. The December issue of Harrington's Photographic Journal ran an article with illustrations on the show, and The Argus reviewed the show on November 18, in which it was noted that:

"The object of the skilled operator nowadays is to leave the mechanical process as much in the background as possible, and by means of rough-surfaced toned papers and studied focus manipulation attempt to challenge art in its own field." (p. 8).

The critic seemed almost to prefer the older subjects "without any adventitious aids", which suggests that Kauffmann's work became progressively softer in focus after 1900, paralleling European trends seen in the various international salons.

The reviewer for Harrington's Journal suggests that Kauffmann's style maintained an ideal balance between the "f64-ites" (the sharp focus school) and the "fuzzy-wuzzies":

"Take for example his 'Thro' the Woods'. Here detail — softened though it be — and the concentration of light calls unconscious attention to the beautiful part of the scene, while the less essential, though necessary setting takes its unobtrusive place by suppression". Harrington's Photographic Journal, Dec. 22 1910, p. 375

This "concentrated appreciation" was obviously to contemporary taste the opposite of the Victorian era's wanton and meaningless over-all focus, which lacked true intellect and feeling.

The mark of Kauffmann's success was the report that Hans Heysen had purchased one work entitled "Sheep". The review and illustrations in Harrington's established that Kauffmann was not a devotee of the extreme impressionist style of pictorialism.

The earliest exponent of this style appears to be Fred Radford, some time of Adelaide and later Sydney, who had a very soft image simply titled "An Impressionist Photo" in Photograms of the Year 1899. Radford is something of a mystery but could possibly turn out to have adopted a pictorial style before Kauffmann. Radford's style owes little to any precedent that Kauffmann would have set by 1898, as the latter's style was not particularly soft in focus at that time.

|

| Briar Rose, c.1930. Private Collection |

| |

|

| Melbourne Street, c. 1910-1930 |

| |

|

The Silent Watcher, c.1920

Illustrated in "The Story of the Camera in Australia", Collection John Cato, Melbourne |

The pinnacle of Kauffmann's career came in 1914 when he had a second one-man show at the Victorian Photographic Society's rooms in March, followed by a reduced show of 52 works at the Photographic Society of NSW rooms in Sydney during April. Both exhibitions were well received by the press.

The reviews in the Melbourne Leader of March 14, and The Daily Telegraph of April 3 both granted Kauffmann status as an artist and praised his blend of soft atmospheric effects, which gave a poetic effect without loss of realism.

By this time a reaction had firmly set in against the "fuzzy-wuzzy" school which, according to Cato and Cazneaux, dominated between 1905 and 1916. Evidently, Kauffmann's more naturalistic style was considered apart from the extremists. Leslie H. Beer, then editor of Harrington's Photographic Journal, in an editorial in the April issue, regretted the "sombreness" and "forced masses", though he admired the "dignified bigness" and bold design of Kauffmann's work. Beer must have changed his opinion by 1919 when he wrote the introduction to Kauffmann's monograph.

The low-key tonal impressionism of early pictorialism became increasingly unpopular over the next few years and Kauffmann's work began to appear old-fashioned. Beer's essay refers to criticism of Kauffmann's artificiality and "fakery", which probably referred to the manipulation of the print to produce such effects.

By 1917 Harold Cazneaux and a group of Sydney pictorialists felt that pictorialism had fallen into a low-toned rut and formed The Sydney Camera Circle to develop a pictorial style true to Australian sunlight. Kauffmann expressed considerable bitterness to Cazneaux in 1934 that he was expected to submit work to Victorian Salons and had even been rejected.

With his reputation, Kauffmann felt he should have been invited to exhibit non-competitively. Cazneaux faithfully recorded Kauffmann's contribution in any articles he wrote but by his death in 1942 Kauffmann was largely forgotten.

Kauffmann continued to exhibit both locally and in overseas salons after 1914. The publication of The Art of John Kauffmann in 1919, which contained mostly late landscapes and urban scenes, is an indication of his prestige. Cazneaux has only recently been honoured in by a monograph on his work.

(Phillip Geeves' Cazneaux's Sydney, 1980, plus AGNSW 1975 Exhibition catalogue)

As well as the monograph, Kauffmann illustrated a book on the Sunraysia district in 1920 and contributed to a Syd Ure Smith book on Melbourne in 1931. Though he did not work on a wide range of commercial assignments, Kauffmann seems to have supported himself on sales of photographs and jobs. He does not appear to have done much portraiture or figure work after 1910.

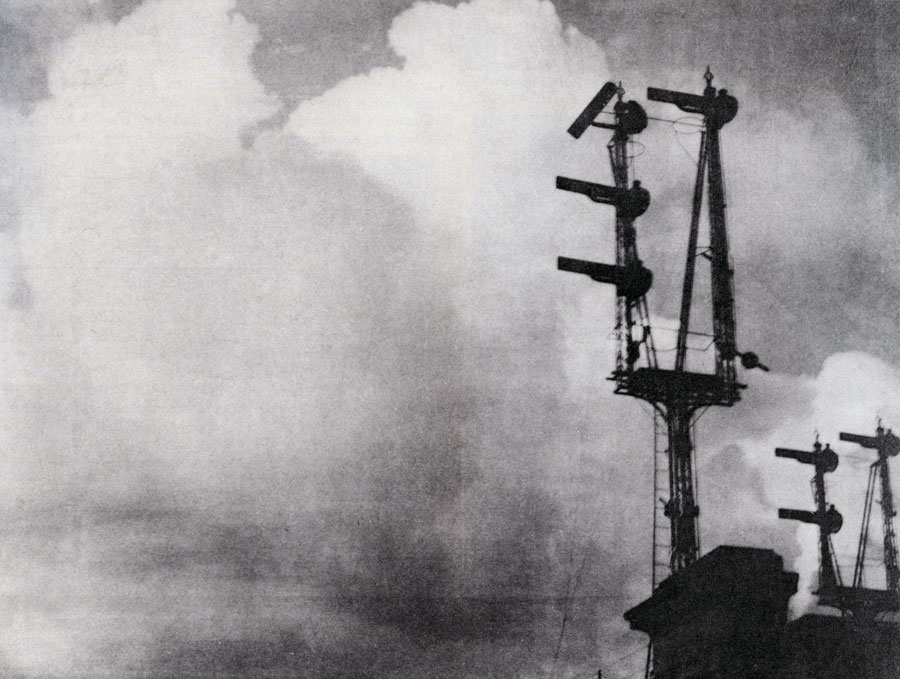

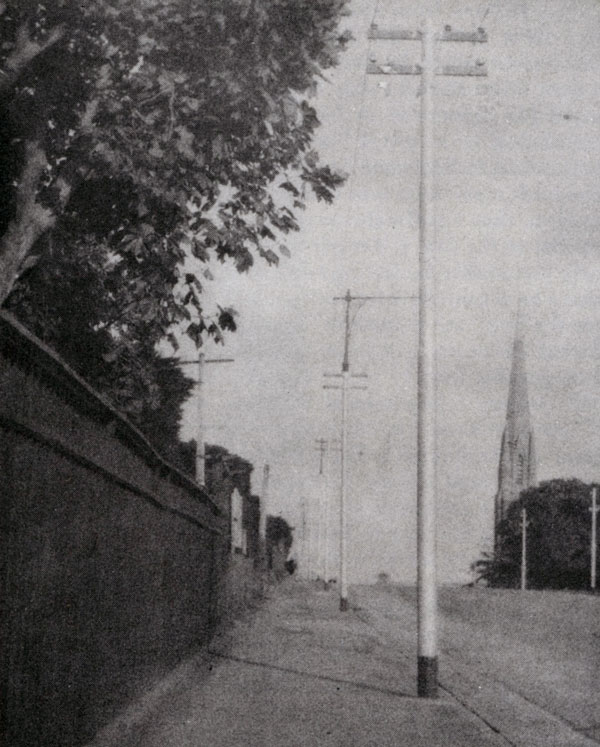

Cazneaux's career was far more varied and successful than Kauffmann's yet in their dedication they were similar. Kauffmann attempted some radical compositions, such as “The Cloud" of c.1914 (in the monograph), and scenes showing telegraph poles that reveal an ability to treat modern industrial elements pictorially.

Some of this type of composition are even more radical than Cazneaux's treatment of such subjects. Perhaps no other pictorialist in Australia succeeded as well as Kauffmann in a poetic but naturalistic impressionism.

Certainly, no other photographer could capture luminosity within a print as well as Kauffmann; however, the romanticism of his treatment eventually was out of odds with the times.

Gael Newton AM (the above essay published in 1980)

More on John Kauffmann - click here

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|

-1907.jpg)