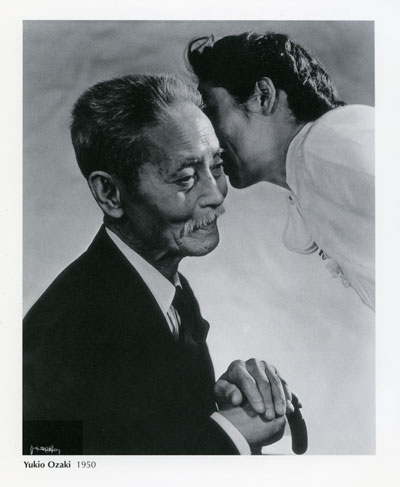

Yousuf Karsh (Ottawa) & Athol Shmith (Melbourne)

the good, the great & the gifted

Camera Portraits

Based on the booklet

for the National Gallery of Australia travelling exhibition

I n the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the middle-classes expanded in size and affluence, the mass circulation of portrait photographs of public figures and celebrities became an industry.

Photographers with talent, technical aptitude, business sense and charming manners found they could become not only specially appointed Court photographers but also the darlings of High Society.

Photography defined and created the very notion of celebrity by catering to the public fascination with images of the stars of the stage and later the cinema. Though separated across the globe and in their relative international fame, both Yousuf Karsh (1908-2002) of Ottawa and Athol Shmith (1914-1990) of Melbourne are 20th-century examples of portrait photographers who continued and excelled in the field of providing the public with glorified and glamourised portraits of public figures.

The National Gallery of Australia holds over 130 prints by Karsh and some 60 by Shmith. The Karsh works were acquired in 1973 by the National Gallery's director at the time, James Mollison, and formed the whole of Karsh's touring exhibition Men who make our world (although there were female sitters included). |

|

|

Shmith's works were acquired through purchases from various exhibitions in the 1970s and 1980s when a new era of interest in Australia's photographic heritage was making an impact, as well as in the form of gifts from the artist.

For sources of inspiration, Karsh and Shmith could take heed of the conventions of painted portraiture going back centuries, as well as the achievements of earlier art photographers.

As modern photographers, both men mixed these historical precedents with technical advances such as better lenses, shorter exposure times, panchromatic films (which were more sensitive to the spectrum), electric lighting and an array of special lighting tools for work both in and out of the studio.

Throughout their lives, both Karsh and Shmith were drawn to the world of theatre and music, and their experience of stage lighting was critical to their success as portraitists of the good, the great and the gifted.

Yousuf Karsh

Yousuf Karsh, who died in Boston in July 2002 aged 93, is popularly known as the great camera portraitist of the most esteemed world figures and celebrities of the mid to late 20th century.

His subjects included politicians, religious leaders, royalty, artists, writers, dancers, actors, singers, musicians, explorers, scientists and physicians.

Born in 1908 to Armenian parents in Mardin, Turkey, Yousuf Karsh had first-hand experience of political strife when the Turks persecuted his family. Travelling alone across the world in 1924 at the age of sixteen, Karsh was able to immigrate to Canada where his uncle, George Nakash, had a portrait photography studio in Quebec. Karsh first trained with his uncle and then in Boston in the portrait studio of fellow Armenian John H. Garo.

Karsh moved back to Ottawa in 1932, where he established his own studio. From the 1970s until he retired in 1994, Karsh had his studio in the lavish Chateau Laurier, a landmark building in the best street in Ottawa. Karsh's mentor, John Garo, had made rather soft, idealised romantic portraits in the prevailing style of art photography, but Karsh developed his own modern look with dramatic, sharp and strongly lit close-ups.

Karsh's experience with stage lighting as a member of the Ottawa Little Theatre was a factor in his technique, and through this theatrical circle he made political and social contacts that led to clients for his business. |

|

|

From as early as 1936 Karsh was becoming known for his modern portraits of visiting statesmen and dignitaries, who were often set against a darkened background, spot-lit like actors on a stage, and shown close-up revealing every detail of hair, skin and clothes. He used large format cameras with up to 8 x 10 plates and huge banks of lights to transform his subjects.

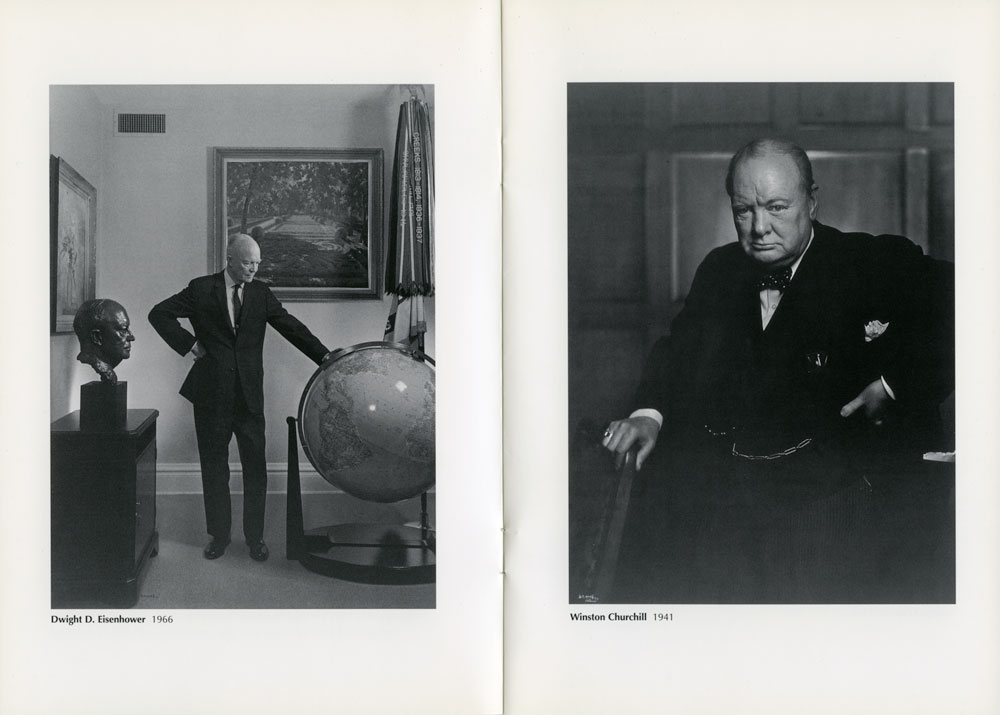

Karsh's international reputation was made when his portrait of British prime minister Winston Churchill — then in Ottawa for a political meeting during World War II — was used on the cover of Life magazine in December 1941.

According to legend, Karsh whipped Churchill's beloved cigar out of his mouth a moment before making his exposure. (By contrast Karsh would later persuade the formidable USSR leader Nikita S. Khrushchev to don his native headgear of a Siberian fur hood and smile like a jolly Santa Claus.)

The portrait of Churchill became the iconic image of the wartime leader and was even the model for his portrait in Madame Tussaud's wax museum in London. Churchill is not 'scowling', as the image is so often described, and its success surely had more to do with making the not very photogenic Churchill exude the right mix of concern, bullying strength and vision.

These were the qualities then needed to reassure the public across the Commonwealth as they faced their enemies in Europe.

Although Karsh credited his beloved mother with being an inspiration to his work, he did not return to Armenia until late in life. From the time of his success with the Churchill portrait, Karsh did, however, spend much of his life travelling across the world to photograph the good, the great and the gifted among world figures, or 'people of consequence' as he called them.

He produced numerous publications, beginning with Faces of Destiny in 1946. Signing himself 'Karsh of Ottawa', the photographer became a celebrity in his own right and world leaders felt slighted if not selected to be 'Karshed'. In many cases Karsh's camera portrait became the best known image of the subject. Karsh, a devout Catholic, had a belief in individual greatness and in role models in society.

This was perhaps fuelled by his knowledge, gained early in life, of how cruel human beings could be to each other. Although his sitters were mostly commissioned portraits, there is a sense in which Karsh put his own imprimatur on a pantheon of well-known people whom he saw as deserving of their fame through merit, not birthright. He did not 'do' glamour per se and his female subjects are handsome rather than 'fair ladies'.

Stories abound about how Karsh managed to get his subjects to co-operate, regardless of the location or how short a session he might have been allocated. As one critic commented, 'Clearly Karsh used a lot more than lighting on his subjects. His conversational foreplay was as spontaneous as his portraits were staged.'2 Karsh also developed a distinctive style of dark, dramatic, large exhibition prints up to a metre in width or height (as shown in this exhibition) with startling depth and detail. Karsh's photographs were the equivalent in the portrait field to the monumental landscape photographs of his American contemporary Ansel Adams.

Yousuf Karsh was at the height of his career in the 1960s and 1970s when he was the star of the Canadian pavilion at the World Expo '67 in Osaka. Several large exhibitions of his work toured internationally in these years. By the time he died in 2002, Karsh had been awarded an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society and almost every possible form of recognition from his photographic peers across the world. He received national and international honours including an award as Officer of the Order of Canada and a number of honorary degrees from Canadian and American universities.

Athol Shmith

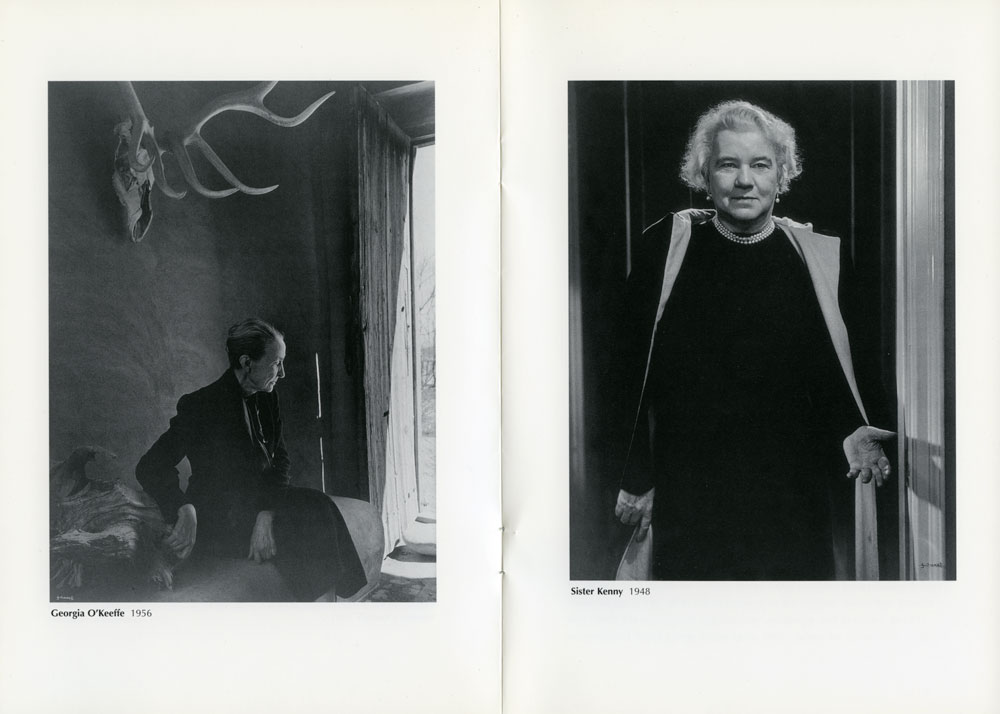

The only Australian in the Karsh collection is a portrait of expatriate Sister Kenny, who developed treatment regimes for poliomyelitis. Karsh had most likely never heard of his contemporary in Melbourne, Louis Athol Shmith, who was something of a legendary character in his home city.

Shmith was born in Melbourne in 1914 and came from a comfortable and cultured middle-class family; his father was a respected chemist and a fine pianist. Athol Shmith played the vibraphone and considered music as a possible career.

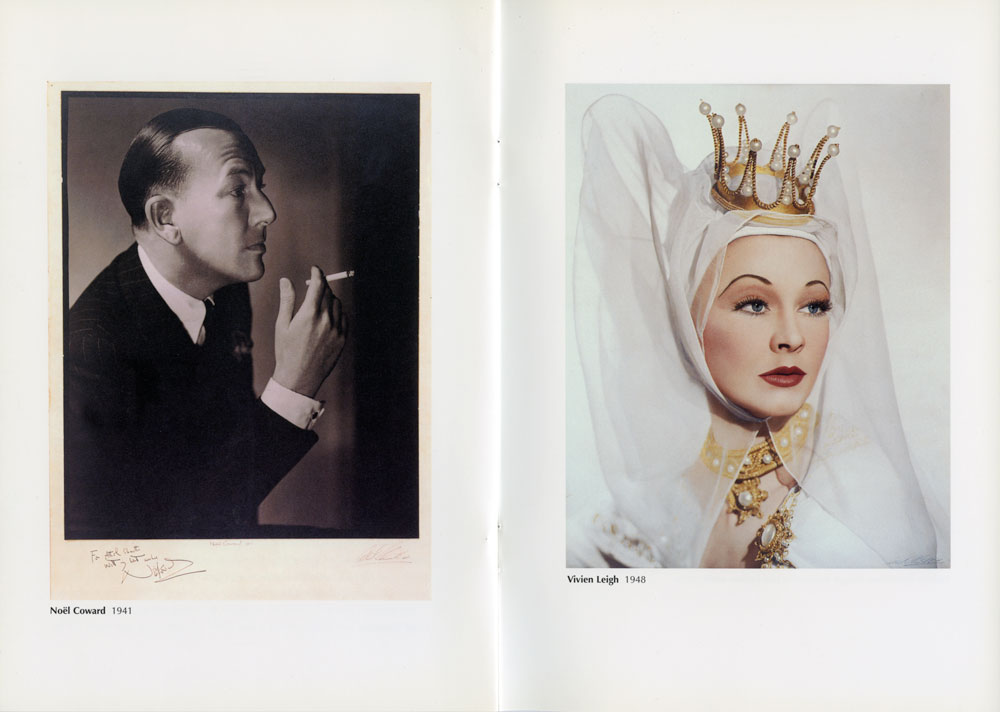

His father gave him a camera as a teenager and what was a hobby became a profession in his late teens when Shmith, who had an interest in theatre and played at charity performances, was asked to take the publicity photographs and stills for a show. He saw there was a career in his former hobby and, supported by his family, established a studio in St Kilda.

For the first five years he specialised in theatre work and society and wedding portraits. In 1939 he moved to a studio in Collins Street (where all the best photographers were located), run with the assistance of his brother and sister. Shmith first made his reputation with society weddings and portraits, but his professional break came in the early 1930s when he gained the contract to take portraits of visiting celebrities for the newly formed Australian Broadcasting Commission. |

|

|

Shmith's work expanded to include a range of commercial advertising and illustration and appeared in local society magazines. He exhibited his works in photographic salons at home and abroad, gaining a Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society in 1933. He also held an appointment as Vice Regal Photographer in Melbourne and had the contract for work for theatre producer J.C. Williamson.

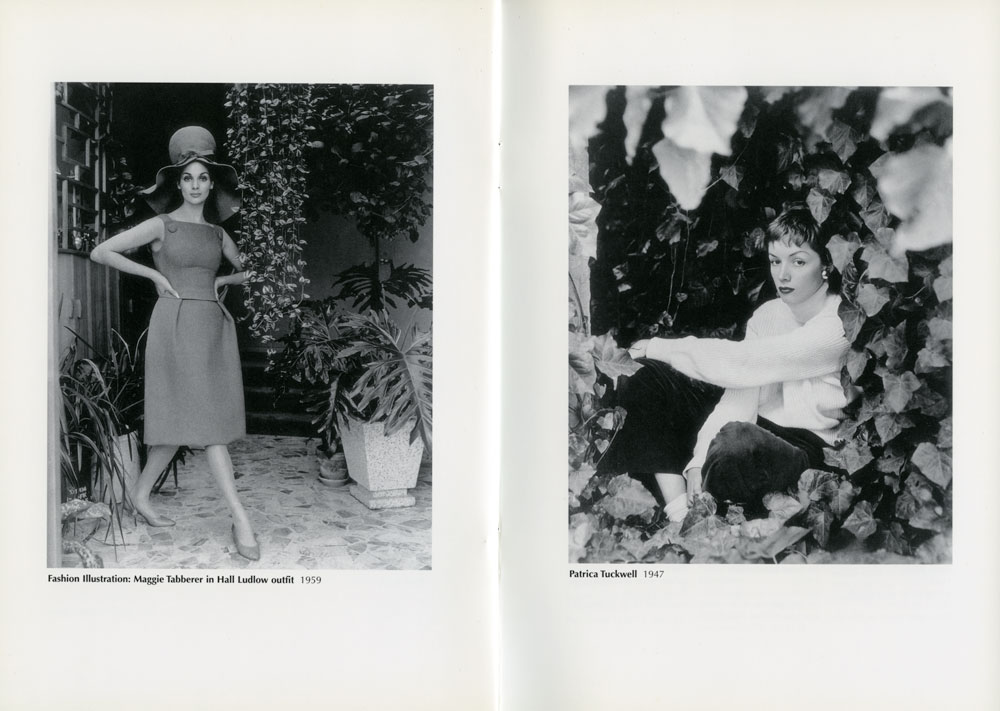

Influenced in his early career by the soft impressionistic style of turn-of-the-century art photographers, Shmith later embraced the clearer light, bolder compositions and design emphasis of modernism. By the late 1930s he was seen as representing a new modern style of work. After World War II Shmith embraced the New Look and the spirit of postwar recovery in fashion illustration, becoming the most respected professional in the field in Australia.

Throughout the 1960s Shmith remained energetic and dynamic in his development of fashion work. By the close of the decade Shmith began to take on roles in photographic heritage and education. In 1968 he helped to establish a photography department at the National Gallery of Victoria and in 1971 closed his business3 to take on a new role as head of the Photography Department at Prahran College of Advanced Education.

Until ill health caused his retirement from the College in 1979, Shmith was a significant support to the rising generation of documentary and artist photographers such as Carol Jerrems and Bill Henson. Shmith's work was largely based in his home city of Melbourne.

Athol Shmith's photographs created a world of grace, glamour and allure. In later life Shmith undervalued his own commercial work but, under the new wave of interest in photography as art, Shmith's work was collected by the major art museums in the 1970s and 1980s and he had a retrospective in 1977 at the Australian Centre for Photography. He was made a member of the Order of Australia in 1981.

A small monograph on his work was published in 1980 and a more substantial one was written by curator Isobel Crombie and published in association with his major retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1989.

Athol Shmith was, like Karsh, urbane, charming and witty but possibly more madcap. Shmith was less concerned with the gravitas and moral exemplar of 'greatness' than with the imparting of elan, style and creative spirit. He was fascinated with his subjects rather than in awe of them. Even though his subjects are most often in a soft and more sensuous focus than the robust men and women in Karsh's world, they often seem closer to the viewer. Shmith, who prided himself on his skill in lighting, had learned much from the model of European modernism and the quirkiness of surrealism.

He was also indebted to the top-lit and back-lit glowing 'Hollywood lighting' style of portraiture popularised by Californian photographer George Hurrell in the 1920s and 1930s. He described his portrait of actress Vivien Leigh in costume as lit by his 'inky dinky light', a top spotlight diffused by tracing paper. Where Karsh made even beautiful women look strong, Shmith treated his female sitters and models as princesses.

Athol Shmith did know about Yousuf Karsh but thought his photographs made the subjects look like 'empty buildings'.4 Both Karsh and Shmith shared an equal passion for their medium of expression. The development of a more rarefied photographic art scene in museums and a new scepticism among the young towards authority figures from the 1960s on led to their styles of work being seen as outdated aesthetically and politically. While different in their mood and approach to the portraiture of the good, the great and the gifted, Karsh and Shmith excelled at their work, and their passion for photography was inextricably linked to the passport the medium gave them to wider and more exotic worlds. Both Karsh and Shmith have extensive holdings in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia.

Further reading

Vorsteher, Dieter and Janet Yates (eds), Yousuf Karsh: heroes of light and shadow, Niagara Falls, N.Y.: Stoddart, 2001

Karsh, Yousuf, In Search of Greatness: Reflections of Yousuf Karsh, London: Cassell, 1963

Karsh, Yousuf, Karsh: A Sixty-Year Retrospective, Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1983 (revised edition 1996)

Athol Shmith, Melbourne: Richmond Hill Press, 1980

Crombie, Isobel, Athol Shmith, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1989

Notes

- The Canadian Government then sent Karsh to London to photograph the other leaders of wartime Britain and Life magazine commissioned portraits of American military leaders.

- Sarah Boxer, 'An Understanding of How to Picture Fame', The New York Times, 11 August 2002, p. 31 (a review of Karsh works at Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York)

- Operated since 1950 in association with John Cato, son of Melbourne photographer and photo-historian Jack Cato.

- In an interview with Peter Adams in 1986, Shmith said: 'In a sense, Karsh's portraits are like empty buildings. He photographs the person's face, not the person's soul. His pictures remind me of Detroit car photos — probably a ridiculous analogy, but everything's just a little too perfect and the end result is rather slick. You are forced to decide what is important about Karsh's work: his collection of subjects, or his collection of pictures.'

Checklist: see attached PDF

For more on the exhibition, including other essays - click here.

Gael Newton was the Senior Curator, Australian and International Photography, National Gallery of Australia

more Essays and Articles

.

|