Indecent Exposures

Twenty Years of Australian Feminist Photography

reviewed by Gael Newton

Essay originally published in Art and Australia - Women

Vol 32 No 3, Autumn 1995

For over two decades women and men have struggled with a new vision to bring women's issues and art activity, as well as media previously invisible such as photography, into the official cultural piture. The goal has been to replace the flat patriarchal and monocular view with a full stereo vision of depth, richness and variety.

For those involved over this period with the causes of feminism or art photography, the recent past is rapidly becoming a foreign country. Two decades is long enough for the pioneers to begin to experience themselves as history - and for a younger generation to emerge with agendas of their own.

Catriona Moore's history of feminist photography in Australia from the late 1960s to the present covers two generations of artists and activists. Moore's writing is not proselytising; it provides the academic rigour and analysis to be expected of a publication based on a doctoral thesis, but also the passion and commitment of a partisan involved with the major events of the period.

The historical study preserves, confirms and empowers. As a woman arts administrator over most of the same period covered in this book I had a frisson of nostalgia, excitement and ownership in reading the pages as events took on contexts not seen at the time. No doubt perceptions from different factions will dispute aspects of Moore's emphases and structuring. Regardless of any future revisions, the perceptions of contemporary participants always remain primary resources.

Curiously the title and chapter headings, with their references to 'bare essentials' and 'faking it', are loaded with the kind of nudge-nudge-wink-wink sexual overtones which male commentators often employ when trying to cope with women in unfamiliar roles once exclusive to men.

This strategy of the author remains as ambiguous as the post-modern phenomena she discusses, in which younger women artist photographers load their images with glamour, allure and other sexual stereotypes as opposed to the 'personal is political' concerns which characterised the first wave of feminism.

In this context Moore encompasses younger women photographers such as Tracey Moffatt and Robyn Stacey as feminist. For traditional feminists, the work of these artists requires something of a leap of faith as to the nature of their critique. One suspects that Moore inclines towards a view that post-modernist work represents seduction and capitulation by the liberated to the modes and manners of the still powerful ruling class.

Indecent Exposures is dedicated to Carol Jerrems, one of the first women photographers in the 1970s to receive serious critical reception and curatorial representation. Interestingly, Moore makes a first attempt at a critical study of Jerrems, which even suggests elements of failure. This discussion seemed truncated; perhaps Jerrems's premature death in 1982 has fostered an element of hagiography. |

|

|

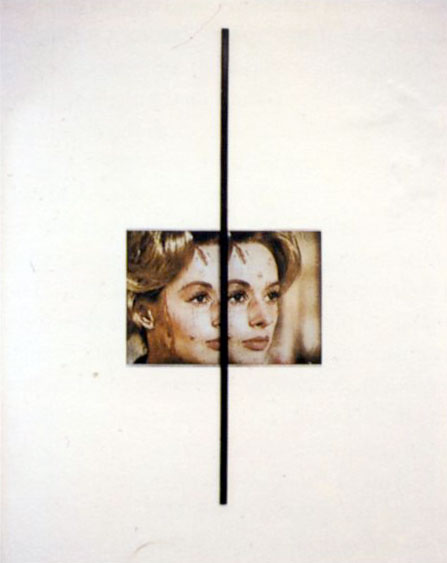

JANET BURCHILL and JENNIFER McCAMLEY,

Temptation to exist, 1986,

two type-C photographs dry mounted and laminated on aluminium sheeting, 50.5 x 76 cm, private collection. |

Or perhaps Jerrems's work and that of earlier feminist photographers such as Micky Allan and Virginia Coventry always contained much more than the limited agendas of feminism and art photography allowed.

The exclusion of discussion about how such first-generation artists have developed in the last decade (some moving away from photography as well as any overt social and political reference) is needed to complement the account in Indecent Exposures.

The references to, and analysis of, art school education of women is a small highlight of the book, and sadly the discrepancy pointed out between the optional feminist courses offered and the sheer lack of female lecturers remains true in present institutions. A major study of outcomes for all art school graduates is needed.

The book is most fascinating and valuable for its preservation and retrieval of works and artists lost from view. Some familiar faces among the ranks emerge as heroes. Sue Ford has been a given in feminist photography since the very earliest days and being reminded of the extent of her work prompts the question: when are such women going to be given the seriously curated retrospectives they deserve?

|

|

|

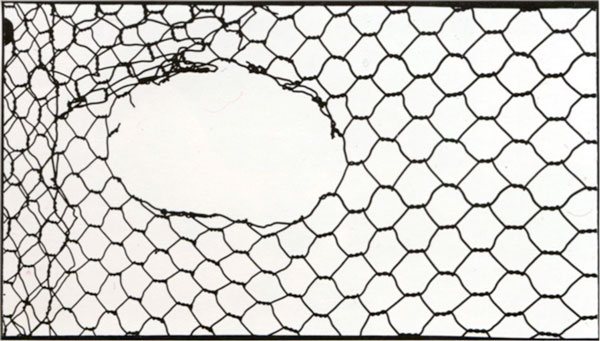

CAROL JERREMS, O, from the series Alphabet,

1968, gelatin silver photograph, 11.1 x 19.7 cm,

National Gallery of Victoria. |

|

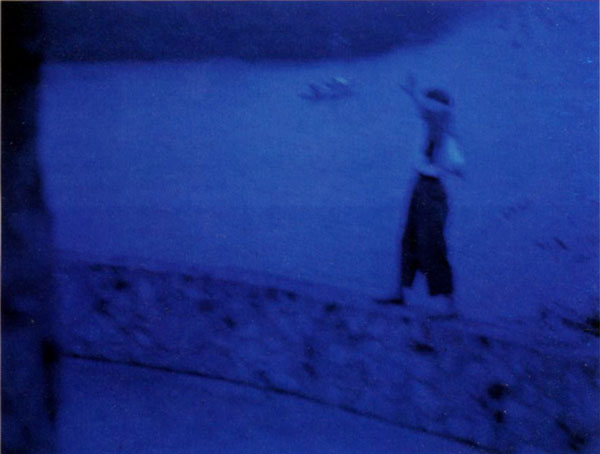

JAY YOUNGER, Anxiety as style, 'Nice blue version':

Noisrev eulb ecin' Elyts sa yteixna 1 (between delusions),

1989, cibachrome, 105 x 119 cms. |

Moore begins her lively introduction with a rhetorical statement engaging the current view that the golden days of feminist photography are over. Specific complaints are made later in the book (as they have been in her other writings and lectures) that many significant examples of women's art dealing with, for example, the messy issues of childcare, nappies and tampons have been passed over by museum collections.

This issue was not well proven for an academic study and a list of works not bought and still available for purchase in the 1990s, as well as comparisons between male and female representation, would have been invaluable in this context.

Work by women photographers was not bought regularly by major institutions until after the early 1980s and no serious data exist for relative numbers of works acquired for the equivalent generation of male artists, nor is it placed in context with buying patterns of other media.

The publishers Allen & Unwin are to be congratulated for adding another significant text to their list. Though this press is not in the coffee-table market, the standard of colour illustrations is good and the monochrome mercifully free of the dishwater grey which is so often the fate of black and white illustrations in books.

It is to be hoped that sales of Indecent Exposures will encourage the production of a larger format book attesting to the visual treasures of feminist photography that is more able to recruit and enthuse a later generation.

It would be sad if Moore's book ended up being a rear view account rather than the beginning of a second wave.

Gael Newton AM is a Canberra-based writer. She was Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia

Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Australian Feminist Photography

by Catriona Moore, Allen & Unwin in association with the Power Institute of Fine Art, Sydney, 1994

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|