THE HOFFOTOGRAAF:

PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHER TO INDONESIAN ROYALTY

Gael Newton

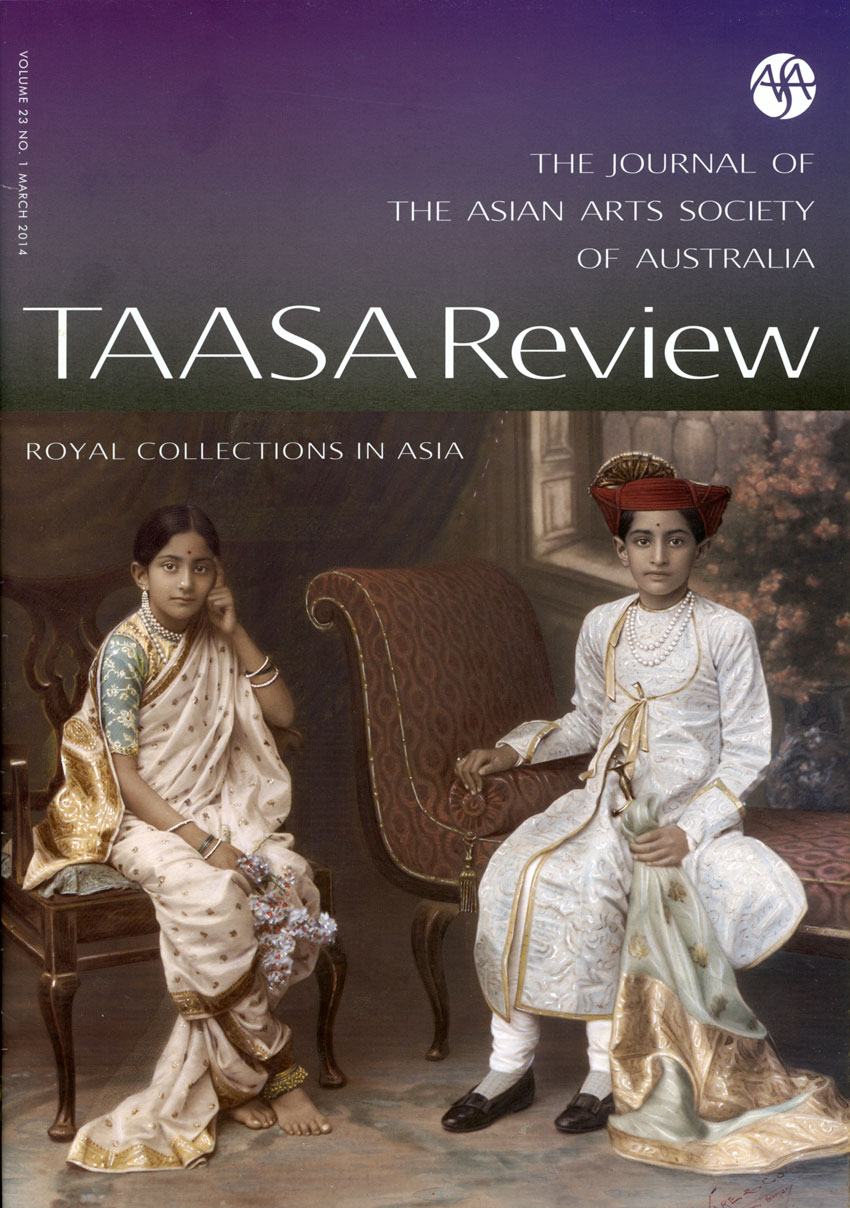

Originally published TAASA REVIEW March 2014*

|

Javanese Prince, son of the Regent of Bandung in bridegroom's dress c.l865, Isidore van Kinsbergen,

albumen silver photograph, 13.5 x 18 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

The first portrait studios in the world were opened in London in 1841 and Prince Albert - ever the enthusiast for new technology - became one of the first Royals to be photographed when he sat to daguerreotypist William Constable in Brighton in 1842. His 'likeness' was a private affair, daguerreotypes were one-off items with limited mass market potential.

Photographs were, however, increasingly used to lend authenticity to drawn illustrations in newspapers and journals. By the late 1850s 'from a photograph' became a featured byline of portraits in books and illustrated papers such as The Illustrated London News.

What made the most difference to the commercialisation of photography from the 1860s was the world-wide craze for collecting celebrity portraits and exotic 'types', made possible by the availability of cheap portraits on paper. In an Imperialist era, the popularity of images of exotic royals in colonial domains encouraged travelling photographers or those in foreign ports, to add these images to their inventory.

In 1859 French photographer AAE Disderi marketed portraits of Louis Napoleon III in the new miniature calling card sized carte de visite (cdv) format he had introduced in 1854, and in 1860 John Mayall marketed a set of cdv portraits of the British Royal Family in a special album that sold in hundreds of thousands all over the anglophile world.

Practitioners of the new vocation of 'daguerreian artist', 'photographist' and finally 'photographer' were quick to apply 'By Royal Appointment' to their products as soon as a royal client patronised their services. A lucky few could be listed at the higher rank of royal or court photographer if they photographed the reigning royal family and entourage.

The concept of the royal or court photographer, the hoffotograaf in Dutch and hofphotograph in German, followed naturally throughout Europe from established traditions of the favoured royal portrait artist.

Stationers across Asia followed suit by selling imported images of European royalty, and studios sought 'By Royal Appointment' status via the patronage of local vice regal representatives or, more rarely, via visiting European royalty by presenting them with albums of local views and personalities.

An early visitor was the Due de Penthievre, grandson of the French King Louis Philippe exiled in England, whose 1866-68 world tour was made into a long running bestseller Voyage autour du monde (1868) by his childhood friend and official companion Ludovic, Marquis (later Comte) de Beau voir.

The pair visited Java for a week in early December 1866 and de Beauvoir collected locally made photographs, including portraits of Javanese and Balinese princes by Isidore van Kinsbergen.

The exchange of painted portraits between European royals and Asian monarchs was an established protocol by the 18th century and this practise was promptly transferred to the new though less flattering, medium of photography in the 1850s.

A number of Indian princes and maharajas posed for and also took photographs from the 1850s. Chinese and Japanese emperors were not early enthusiasts for photography, although other elite aristocrats and officials in both countries were early experimenters.

The Thai King Mongkut (Rama IV) was the earliest and most assiduous of monarchical enthusiasts for the medium in Asia. He had the French bishop in Bangkok import a daguerreotype camera in 1847 and one of the Bishop's priests learned to operate it.

King Mongkut received another instrument from Queen Victoria in 1850 and actively sought to have his own relatives trained in photography. His brother Vice-King Pinklao and several courtiers, become adept over the next decades through training and observing foreign photographers at work.

In November 1857 Queen Victoria received a daguerreotype portrait of Mongkut - now attributed to the Thai court photographer Luang Wisut Yothamather. Being photographed was a political performance the King well understood. He also sent a daguerreotype portrait of himself and Queen Debsirindra to President Franklin Pierce in 1856 as part of an exchange of gifts honouring the 1856 Harris Thai-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce.

Both portraits survive as the earliest extant photographic portraits of an Asian, indeed of any, reigning monarch. Mongkut sent similar portraits to Pope Pius IX and Napoleon III. Mongkut's son and heir, King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) continued the interest and took up the camera personally, a practise continued by the present day King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) (Morris (ed) 2009).

The earliest portrait photographer known to arrive in the former Dutch East Indies was Adolph Schaefer (c. 1820-73) in 1844. A German professional daguerreotypist working in The Hague, Schaefer had learned that medical officer Juriaan Munnich in Jakarta had failed in his 1841 Dutch Ministry of Colonies commission to 'test out the heliographic apparatus in the tropics' with a primary aim of securing daguerreotypes of Javanese antiquities and the Buddhist monument Borobudur.

Soon after his arrival in Jakarta, Schaefer succeeded in adjusting chemistry to tropical conditions and was offering the elite of Batavia the new art of daguerreotype likenesses. The following year he made views of the reliefs at Borobudur, over 50 of which are held in the Prentenkabinet at Leiden University Library (Wachlin 2007: 739-741).

None of his portraits are known to survive but Schaefer may have been the maker of a daguerreotype that appears to be the basis for an 1853 coloured lithograph 'Een Javaschen prins - Un prince Javanais' (believed to be Hamengkubuwono V r. 1820 - 1855) by Jakarta-based artist Auguste van Pers (1815-1871).

The image appears in the first part of the 56-plate Nederlandisch Oost-Indische typen series published by subscription in The Hague by lithographer CW Mieling from 1853-62. This huge undertaking includes a few plates that are startling in their realism and the look-to-camera expression of those posing for a photographer.

A stream of itinerant daguerreotypists passed through the Indies in the 1850s; it is not known if any sought or gained access to royal clients. Swedish itinerant daguerreotypist and photographist Cesar Diiben (1819-1888) reported on his visit to take photographs at the Kraton in Yogyakarta in January 1858 that he had photographed the family of Hamengkubuwono VI (r. 1855 to 1877).

The Javanese princesses featured in one of the 15 lithographs based on his photographs in Diiben's 1886 memoir may have been from Yogyakarta. Diiben seems not to have been granted a sitting by the Sultan himself but responded to his request to instruct a court member in the photographic process and presented his camera to the Sultan as a parting gift.

The Hamengkubuwono royal family at Yogyakarta appears to be first in Indonesia to be photographed and to have had their own official photographers in the 1860s. No daguerreotype images are extant but the new wet-plate photography on paper introduced in 1851 in England, which replaced the daguerreotype by the 1870s, greatly facilitated the circulation of images made off glass negatives.

The young English photographers Walter B Woodbury (1834-1885) and James Page (1833-1865) of the Woodbury & Page atelier set up in Jakarta in 1857 after their not very successful Australian colonial ventures. Walter Woodbury had been acknowledged as the 'best glass artist' in Melbourne in 1854 by his employer, the skilled American daguerreotypist PM Batchelder.

Upon their arrival Woodbury and Page determined that there was European interest in images of antiquities and the inhabitants of 'Princes Land' in central Java. The duo made their first field trip to Yogyakarta and Surakarta in 1858 and marketed their first images of Indonesia in England in 1859.

These were published later in 1861 by Negretii & Zambra as expensive albumen on glass stereographs and again as richly coloured lantern slides in the 1860s by Newton & Co using the woodburytype process patented by Walter Woodbury in 1864.

Illustrations after the first series were published in The Illustrated London News, 31 July 1861 and included Javanese aristocrats, court dancers and musicians. Walter is also most likely the maker of two half plate ambrotype portraits of Hamengkubuwono VI and his principal wife produced around 1858.

In 1879 under their successor, Walter's younger brother Albert Woodbury, Woodbury & Page studio acquired a 'By Royal Appointment' status to the Dutch Crown. Their inventory listed numerous royal portraits, although none are named and pictures of sultans are lumped in with 'native types'. What the sultans thought of this presumably demeaning hawking of their images around the world is not known. As in British India, the Sultans and Rajas of the Dutch East Indies were never granted the status of monarchs.

Woodbury & Page were not the only photographers active in Indonesia in the 1850s and 60s. The Flemish-Dutch theatre performer and artist Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821-1905) began work in Jakarta in the mid 1850s with French photographer AF Lecouteux (Asser et al 2006).

Van Kinsbergen was favoured by the new Dutch Colonial Governor-General, Baron Sloet van der Beele and accompanied him on his 1863-65 tours of the residential districts of Java, Madura and Bali, and the four independent royal territories. By the mid 1860s, van Kinsbergen had an impressive repertoire of Javanese 'native types' and royal portraits in which the models have a strong presence as individuals.

His images were widely distributed, appearing as woodcuts in a number of European and American magazines but he does not appear to have called himself a hoffotograaf.

One of the first to claim the title of a photographer to the kratons was sergeant major and drawing master Simon Wilhelm Camerik (1830-1897). A Banda-born Dutchman, possibly part Indonesian, he may have trained in the Netherlands. He was working in Semarang as a photographer by 1864 and in that year marketed a set of 'principal native grandees' of Surakarta, Yogyakarta and Magelang as well as some views of Prambanam in the Semarang newspaper De Locomotief of 29 August.

By 1866 In the Java-Bode of 17 February, he is listed as 'Kunstschilder en photograaf van Z.H. den Sultan van Djocdjacarta' (painter and photographer to the Sultan), an appellation also stamped on the backs of his cdv portraits of the vice regal resident Adriaan Jan Hendrik van der Mijll Dekker. Camerik also photographed the Surakarta Sultans Pakubwono PX and Mangkunegara IV and some of the same images appear among the 'types' marketed by Woodbury & Page in the miniature carte de visite format.

Camerik ceased work as a photographer after 1870 but apparently taught Kassian Cephas (1845-1912), one of the entourage of Hamengkubuwono VI and an early member of the Javanese Christian Church, who became the first and only indigenous hoffotograaf in the Indies.

Cephas set up his own studio in his Jakarta home in 1871. By 1875 he was advertising his services as 'CEPHAS Photographist ... photographer to the Sultan', in De Locomotief of 9 July.

He remained closely associated with the Kraton and in particular worked with the Sultan's Dutch physician Isaac Groneman, a dedicated scholar of Javanese culture and antiquities. |

|

|

| |

Male court dancers, Yogyakarta Kraton c.1885, Kassian Cephas, albumen silver photograph, 9.4 x 13.6 cm.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

Groneman published several elaborate publications on Javanese art and dance performance in the 1880s to early 90s that gave prominent credit to 'Hoffotograaf K. Cephas' and earned Cephas honorary membership of local and Dutch societies.

Cephas was routinely described as the hoffotograaf Cephas in newspapers and returned to duties at the Yogyakarta kraton after 1904 as his son Sem took over the Cephas studio.

|

Auguste van Pers ‘Een Javaschen prins – Un prince Javanais’ in 'Nederlandisch Oost-Indische typen',

CW Mieling, The Hague 1853–62.

chromo-lithograph after a daguerreotype, 31.7 h x 24.5 w cm. National Gallery Australia |

| |

|

Djokjakarta. Court officials of Paku Alam VII bearing state regalia, c 1925, Tassilo Adam,

gelatin silver photograph 21 x 25.2 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

By the early 20th century, foreign photographers undertook the lesser role of 'By royal appointment'- meaning supplier of goods and services. Such status (to the Dutch Crown) appeared on prints by the Surabaya studio of Armenian photographer Ohannes Kurkdjian (1851-1903) following presentation of his album of the local celebrations for Dutch Queen Wilhelmina I's coronation in 1898, and was retained until the studio's closure in 1936.

One who did work for the four principalities in the 1920s was German Italian ethnographic photographer Tassilo Adam (1878-1955). Adam worked extensively with the Sultans at Yogyakarta and Surakarta to make detailed records of dance and musical performances in the mid 1920s.

Although not claiming the 'hoffotograaf title, Tassilo Adam combined the role of favoured court photographer with that of dedicated scholar. A number of his royal portraits are held in the National Gallery of Australia's Indonesian photographs collection and a unique set of his personal albums was recently acquired by the Gallery.

As recent scholarship has shown, King Mongkut and his descendants in Thailand became adept at strategic diplomatic and 'media management' using gifts of official state and family portraits. Susie Protschky (2012) and other researchers have demonstrated that the sultans of Indonesia, several of whom became amateur photographers in their own right, were similarly adept.

Only Hoffotograaf Cephas, however, filled the comparable continuous and active service of the European model 'royal' photographer.

REFERENCES

Asser, Saskia E,, Wachlin, Steven, Theuns-de Boer, Gerda, 2006. Isidore van Kinsbergen, 1821-1905: Photo Pioneer and Theatre Maker in the Dutch East Indies. KITLV Press, Leiden

Morris, R.C. (ed) 2009. Photographies East: The Camera and Its Histories in East and Southeast Asia, Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

Protschky, Susie. 'Negotiating princely status through the photographic gift: Paku Alam Vll's family album for Crown Princess Juliana of the Netherlands, 1937', Indonesia and the Malay World, 40:118(2012): 298-314.

Steven Wachlin, 'Indonesia (Netherlands, East Indies)' in John Hannavy (ed) Encyclopaedia of nineteenth-century photography, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, New York London, 2007, vol 1. pp. 739-741.

* Article above originally published in TAAASA REVIEW Volume 23 No 1, March 2014

The Journal of the Asian Arts Society of Australia |

|

| click on image above to link to the Asian Arts Society of Australia |

Gael Newton was Senior Curator, Photography at the National Gallery of Australia until September 2014. She had developed its collections of Asia-Pacific photography, particularly from Indonesia.

This was boosted in 2006 by the acquisition of the collection of Amsterdam rare book and print dealer, Leo Haks and is showcased in the Gallery's 2014 exhibition Garden of the East: photographs from Indonesia 1850s-1940s, 21 February - 22 June.

www.nga.gov.au/gardeneast.

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|