Spell O!

Richard Daintree & the Australian image

Originally published in Voices, Summer 1992-1993, A National Llibrary of Australia quarterly

|

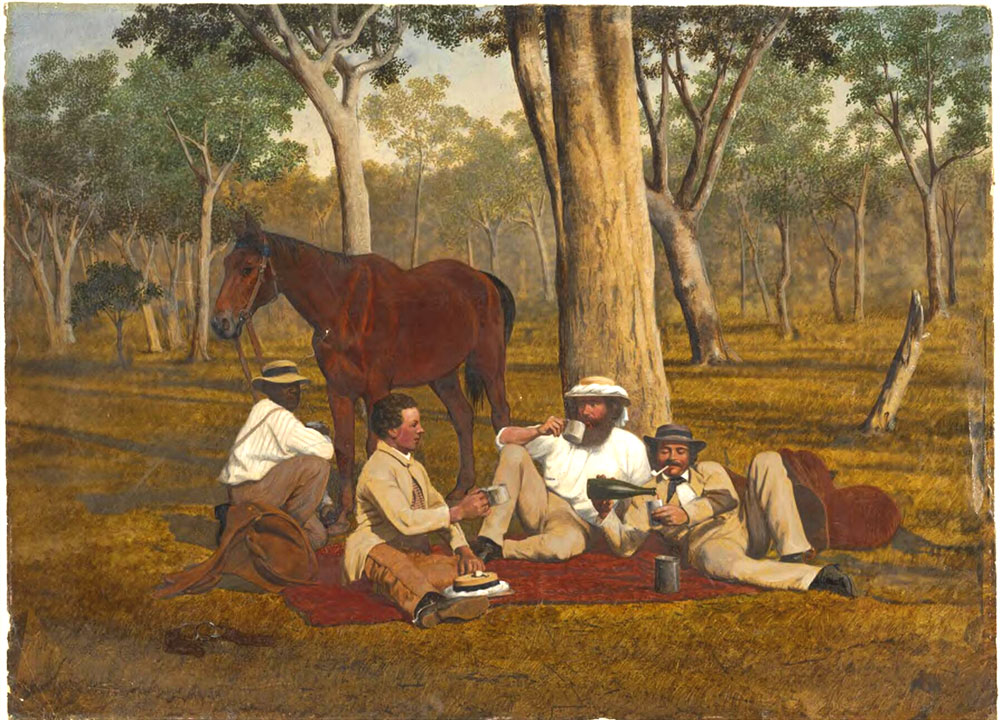

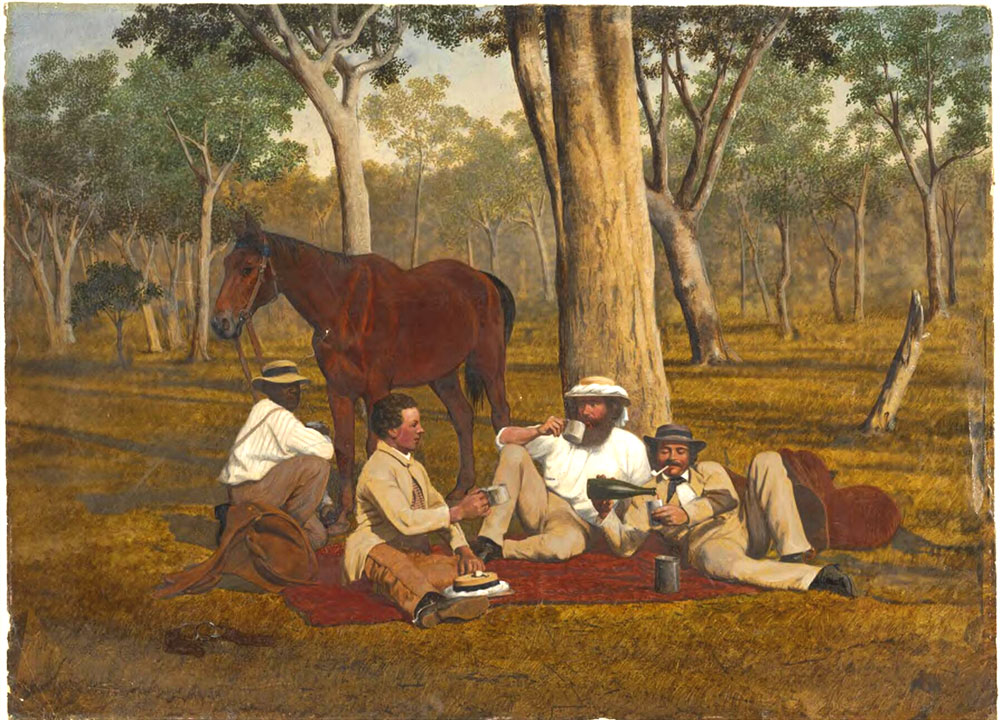

Richard Daintree, 1832-78, Bush Travellers, Queensland, c. 1866, albumen silver photograph, overpainted in oils, 44 x 60.7 cm.

Also known as Spell 0! Rex Nan Kivell Collection. From the Pictorial Collection |

Daintree is a name best known today for the conservationists' campaign to block development of the Queensland rainforest area named after English-born geologist and photographer Richard Daintree (1832-78). Which side of the conservation debate Daintree might favour, if he was miraculously transported to the future, is by no means clear.

Speculation on one of his images Bush Travellers Queensland of about 1865, provides some answers by revealing his attitudes to land use. A large and vivid print of the image, also known as Spell O, is held in the Rex Nan Kivell Collection. It is most unusual for a photograph of the period, as its size and appearance are of a crude oil painting. However, a distinctive feature of Daintree's work was his presentation of coloured photographs in exhibitions.

Daintree happily applied both factual and colloquial titles to works in exhibitions specifically promoting emigration to Queensland. The target audience, pastoralists, selectors, gold diggers and labourers, some of whom Daintree recognised might be illiterate could read the image as anticipatory of their own purposeful travel and settlement in a potential picnic land.

Daintree was quite conscious of the general superiority of pictures to text. The former: will do more to find us favour in the opinion of the emigrant and capitalist than the writing of very many books and even very many lectures.

Why should his comments sound like a discovery? Older authoritarian institutions of church and state had long experience with the use of pictures for indoctrination. However the mid-nineteenth century was a modern era with an independent public who needed to be wooed with attractive advertisements to the benefits of consumerism and emigration.

Daintree had no doubt visited the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and read the massively popular Illustrated London News. He like others with a message for the public at large knew the value of attractive images. Photographs could not be reproduced in newspapers at this time but Daintree pioneered an Australian practise of utilising photographs strategically in public exhibitions.

As early as 1858 he produced with Frenchman Antoine Fauchery the first album of views offered for sale in Australia and in 1872 an illustrated guide for emigrants to Queensland. The visual appeal of the print Bush Travellers, as a result of its over-painting in oil, also arises from the charm of the subject; a relaxed group of men who have stopped for a late afternoon smoko and drink. The image speaks of being at ease in the land. Our bush travellers are hardly earnest heroic explorers subject to the dangers of an alien territory. They have been able to carry bottled beer or wine and sit comfortably on a rug.

The title and the presentation with informative images of the agricultural, pastoral and mineral resources available to emigrants to Queensland establishes that the image is not of a picnic as such. There is a clear impression that journeying through the land is not arduous or pioneering in the sense of a battle with an untamed land. These travellers belong to the phase of exploitation of the colony rather than first exploration.

Is there also present a narrative element from themes in popular literature?

The central figure (who bears a resemblance to the full-bearded Daintree himself) sits relaxed but upright, looking out of the picture. He wears a cabbage tree hat with kerchief making him look like an explorer. To his lower left a rather raffish looking 'mate' slouches on the ground, benignly intent on his drink and pipe.

Somewhat isolated in the foreground a noticeably lighter complexioned young man (a new moustache appears to be growing on his upper lip) sits more formally, even a little uncomfortably, and extends his mug ready for a drink to be poured. His more clean shaven face, buttoned coat and cravat suggest a class distinction or a situation in which the older men are his hired guides. It is tempting to match the image to the tales of the 'new chum' in Australia—the raw English youth who will learn such basics as keeping his hat on and pouring himself a drink.

In the rear an Aboriginal man crouches, mug in hand, apparently tending an unsaddled horse. The position of the Aborigine on the outer edge and his relationship to the horse would suggest that in this land the original inhabitants have been brought into a peaceful service to the new owners.

It is not known exactly when or where Daintree made this image. The landscape is parklike and spacious. The men sit under a tree that extends to the newcomers a beneficent shelter and it is easily imagined that their place will be taken up by the drover or settler. The image has the peaceful quality found in John Glover's 1830s paintings of his property Patterdale in Tasmania.

It is possible that the exposure was made as early as 1863, when Daintree took leave from his position on the Geological Survey of Victoria to inspect four blocks of leasehold land on the Clarke River near Bowen, Queensland. Daintree had invested in a selection with partners Joseph Hann and his two sons William and Frank. By early 1864 Daintree had moved his family to the north and added to his experience as a nomadic geologist the role of pastoralist. Or the image could be as late as 1869, from the Gilbert River area in the Cape district on the last of the prospecting trips which he conducted as official geologist for the Queensland Government. During his travels Daintree had escorted a number of prospectors looking for gold.

The image coincidentally is from the same time as French artist Edouard Manet's famous 1863 Dejeuner sur I'Herbe, of 1863; the subject of many interpretations by later artists. The antipodean picnic, however, carries a meaning in a land under subjugation and development, removed from the traditional fete champetre of European art.

|

Portrait of Richard Daintree, 1832-78,

from Australian Sketcher, 17 May 1873.

From the Pictorial Collection. |

|

|

One simply does not picnic in alien territory. It is an activity for the peripheries of settlement. Nature has first to be made safe for the theatre of the picnic to occur.

Bush Travellers was first exhibited in 1876 at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition and included under the alternative title Spell 0 in a display of over 200 of Daintree's photographs in the Queensland Court at the Sydney International Exhibition of 1879. This was a year after Daintree's early death in London aged 46—two years after his resignation after four years as Agent-General for Queensland. Although in ill-health for the last two years of his life, Daintree may well have organised the Sydney International showing.

Daintree's display at the Sydney exhibition drew the attention of the Sydney Mail reporter who found the images artistic, if a little florid in colouring, and recognised their role as effective immigration advertisements. The reporter also concluded that 'stockmen in Queensland have given up the billy, and carry about with them instead, bottles of Queensland wine or beer'. Evidently beer had not yet reached its later status as the drink for Australian men.

Daintree's work as a photographer was lost from view from the 1880s until the 1950s when the first histories of the medium in this country were written. Recognition of the particular use Daintree made of photography for record and promotion came in 1965 with the publication Richard Daintree: A Photographic Memoir by historian G. C. Bolton. Bush Travellers appears not to have been published until the 1970s. |

Apart from its prominent inclusion in Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839-1988, Bush Travellers has never enjoyed the circulation or popularity of works such as S. T. Gill's chronicles of the goldfields. The hybrid character of the print, half-painting, half-photograph, ensured that most researchers treated the image as a half-caste.

The desire to resurrect an image and counter the prejudice against mixed media caused me to assign Bush Travellers an honoured place in the Australian National Gallery Bicentennial exhibition Shades of Light. Of over 800 images in this exhibition, Bush Travellers resonated with perceptions about the role of photography and the way in which the placement of figures, particularly at rest, in Australian photographs tells more than the story of technical developments. As a figure group set in a landscape, Daintree's image of the picnic, an image of relaxation or active recreation, also tells the story of the literal and metaphoric advance into the terrain by the settler/appropriator.

The bulk of Daintree's photographs are geological and landscape records. Groups of people occur most frequently in the context of their work or settlement of the land, and more so after the mid-1860s. His practice of having exhibition prints coloured was established by 1858 but there is no evidence that Daintree did any artwork of his own. His attention to aesthetics was not due to frustrated artistic ambition, but to his pioneering understanding of photography as advertising and as popular education.

Despite the attention that Daintree has received we are still presented with far more information on his technical and scientific achievements. Publication of his letters would give a more personal picture but it would also be fascinating to find diaries which might give more clues to his cultural interests and might reveal Daintree's awareness of the work of S. T. Gill. Was Daintree the utilitarian character as he is presented? Comments in his emigration guide, Queensland, Australia, could be simply conforming to the romanticism of the bushman already well established by the 1850s or an expression of Daintree's own experiences and attitudes:

As in all the Australian colonies, the squatter was the pioneer of all industrial pursuits. He it was who introduced stock, and underwent all the expense and risk of occupying the new territory. The agriculturalist, miner, and manufacturer followed, in the more or less remote luture. The life of a squatter has peculiar charms to those who have a love for a healthy occupation in the open air, with constant exciting employmeni; and this applies more especially to life on a cattle station.

Not only has it charms for the squatter, or owner of the station, but also to the stockmen employed by him. The genuine stockman seems to be most at home when in the saddle, and most happy when in full gallop after a mob of cattle. It was indeed, in many cases, love of adventure and excitement that led to the choice of this occupation by master and man, as pioneer squatter and stockman.

How autobiographical are these sentiments? Did Daintree arrive as a 'new chum' and embrace the outdoor life and equality of the goldfields? On the one side, in endorsingemigration and presenting a particularly seductive image of the life to be had in Australia, Daintree could cite his own basically positive experiences as an emigrant.

Daintree had come to Victoria as a young man of 20 in 1852 seeking a warmer climate for a weak chest, as well as adventure and opportunity. He tried his fortune as a gold digger but despite his training as a geologist succeeded no better than thousands of disappointed amateurs. From 1854-64 he was employed on the Geological Survey of Victoria, returning briefly to England for further geological training in 1856. Photography was added to his skills by 1857 when in a purely entrepreneurial mode he joined with Frenchman Antoine Fauchery to produce the first album of Australian photographs offered for public sale.

Daintree's photography was largely associated with his scientific work where it was initially used for convenience and perhaps compensation. There is little evidence that he was a skilled draughtsman or topographical artist. He experimented with a number of processes, which indicates a technically inventive side to his character. Much of his time in Australia was spent in the field and it appears this nomadic existence was quite congenial to him.

His time in Queensland as a property manager, despite the fact that he was the son of a farmer, does not seem to have engaged his interest. Nor was Daintree particularly keen for personal reward. He successfully identified a number of goldfields in Queensland but was happy to have the satisfaction of correctly interpreting geological formations rather than exploiting his finds. His scientific passions were genuine and had a theoretical bent and his last hopes were for continued work with photomicrography. Perhaps his horizons were to do with the expanding scientific and utilitarian prospects endemic to the nineteenth century.

Daintree is referred to as an amateur photographer even though he operated as a commercial studio photographer during his brief partnership with Fauchery. His work was consistently applied. Photography for him was not a hobby enthusiasm as it was for many gentlemen amateurs of the period. Few of his personal or fami ly portraits have survived—if they ever existed.

Yet in looking at his personal history it can be argued that Daintree also knew about failure on the fields and the dangers of entrepreneurial and pastoral effort. Daintree experienced first hand some of the familiar tragedies of pioneer settlers. His partner Joseph Hann drowned; Mary Hann as well as Daintree's sister-in-law died of tropical fevers.

|

| Photograph of a bush picnic in Gippsland in 1886 by unknown photographer. From the Pictorial Collection. |

Aborigines were by no means as quiescent as the Bush Travellers image implies and numerous economic and climatic disasters effected the pastoralists, from dingo attacks to spear grass and world slumps in prices. Flies, fevers, and recessions, problematic relations with original inhabitants and native animals are absent if not banished from Daintree's images.

Was this blindness on Daintree's part, or deception? Promotion and education are never far from turning to propaganda. Our poor 'new chum' could have had a sorry fate at the hands of his 'guides'. Many an unwary amateur investor of the 1980s in far-off Queensland paradise blocks has learned to distrust the developers' colour brochures.

Daintree's greatest personal success came from the understanding he had that his photographs could be presented in exhibitions as a crucial means of conveying information about some topic in an attractive way which would elicit public interest. Daintree offered the Queensland Government a display of photographs and minerals for a special Exhibition of Art and Industry in London in 1871. Queensland had little in the way of artistic or intellectual products to offer and raw products were not wanted for that exhibition.

Daintree's display was a great success, and photography saved the day for a colony only established in 1859. This initiative led to Daintree's appointment to a highly paid position as Agent-General for Queensland which offered him an opportunity to develop fully his vision of how public promotions should work. As it turned out, the job was complex and Daintree had to resign his position due to poor health and complaints about his management.

Bush Travellers was not the first photograph of a picnic in this country. That honour—not determined because it has not been sought— probably belongs to a stereograph of about 1858 by Professorjohn Smith of himself and friends at Lane Cove River in Sydney. Daintree's image elevates the picnic to a national level away from the excursionist or personal souvenir. John Smith's picnic is a souvenir.

|

| Nicholas Caire, 1837-1918, Camping Ground, Stoney Creek, Lome. From album Victorian Views, 1905. Caire Collection. From the Pictorial Collection. |

During the first decade of photography in this country images produced were predominantly studio portraits. The relaxed image or the spontaneous action snap shot' could be evoked only by careful posing and sustained stillness. Daintree's image could only be achieved by posing over 20 seconds. He did use a 'dry preservative' process which may have alleviated the need to carry all the equipment of wet-plate photography on his Queensland soj ourns but this would not change the need for long exposures.

Classic picnic shots became more common in the 1860s, appearing mostly in the personal albums of amateur photographers—foreunners to the tide of images that came in the 1890s with widespread amateur photography and more convenient dry plate processes and, finally, Kodak ease of image making. These images of the personal domain swell in number from the 1850s on. This can be seen as merely a technological progression but its partner is the literal swelling of the original emigrants into a national swarm.

As these images proliferate in national consciousness via personal productions and reproduction from the 1890s on, it is as if they displace the original Aboriginal inhabitants whose figures provided the foreground interest scale and overture to the drama of settlement. Images of Aborigines in their land rarely convey ownership; their lack of material culture speaking of a nomadic existence, where the picnic denotes a permanent base to which the revellers return from a foray in the bush.

The picnic image speaks of comforts temporarily dropped and social conventions relaxed. It is a mental as much as a physical sojourn. People picnic to draw solace from places which have been tamed and which have lost the power to control their lives. In the picnic image, landscape represents a change of environment. The terrain of the picnic needs to be different from the norm and to be perceived as such.

What significance then does Tom Roberts's painting Sunny South, of 1885, hold wherein naked white men desport themselves on a coastal beach as Aborigines had been depicted in early topographical views? And what of the popularity of Nicholas Caire's photographs from the late 1870s to 1910, in which hermit characters, men, women and children, picnic deep within nature's ferny bower? Caire presents images in which for the first lime a sense of the redemptive beauty of the landscape of Australia is presented, with the terrain not seen as suitable only for development or study.

By contrast Daintree's oeuvre is not the story of passionate engagement with a new homeland. Yet in some respects Daintree was an Australian more than an Englishman. His efforts went to communicating about the value of the place.

Large urban conglomerations grew in the nineteenth century beyond all imagination. Since the nineteenth century the consecrated wilderness also exists for recreational use of the urban dweller. Contemporary Australians are the inheritors of the picnic experience rather than the pioneers.

|

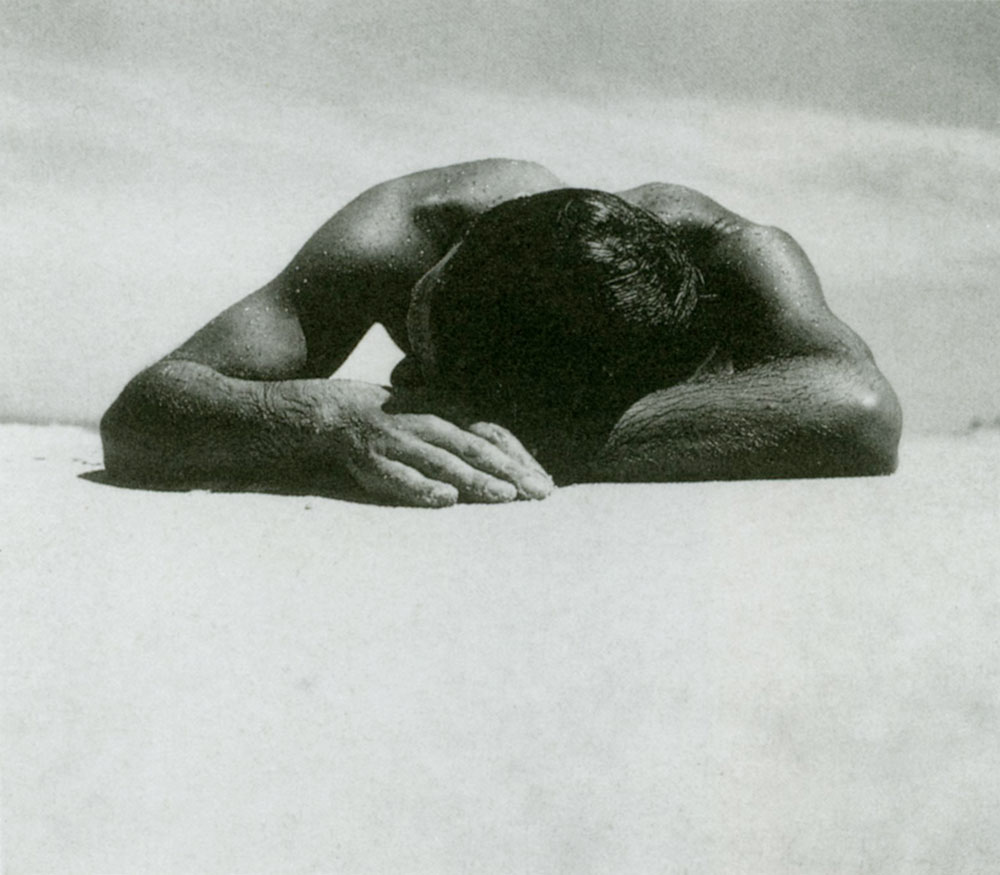

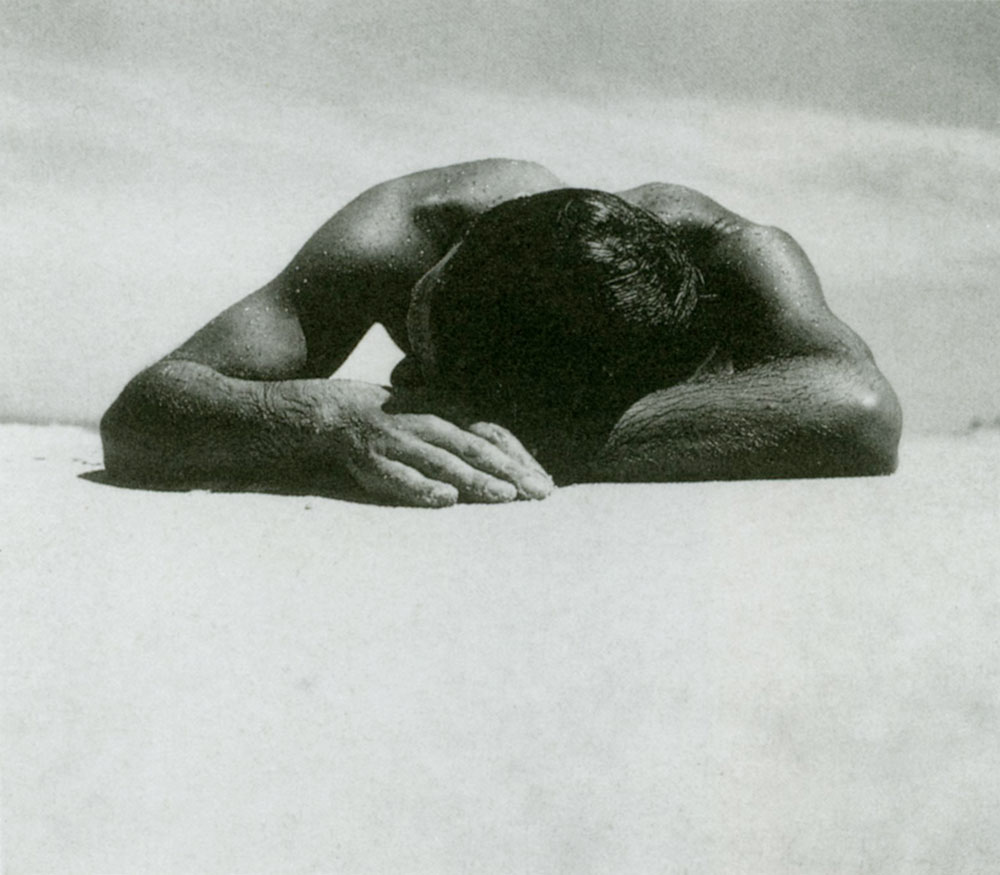

| Max Dupain, 1911-92, The Sunbaker, 1937, gelatin silver photograph. Private collection. |

Reaching forward in time from the perspective of the image of recreation, the late Max Dupain's now iconic Sunbaker, oi 1937, is more complex. Here a white man (a 'Pom' according to information following Dupain's death in July) becomes rocklike, as powerful as the symmetry of Ayers Rock (pictures of which were popular in the i930s for the first time). He seems to merge with the ancient land—a picture on one level of the displacement of the native, replaced by a 'black' white man also now naked in the land and under the sun. This image of abandonment under a southern sun has come full circle. Produced as a personal statement by the photographer, such sunbaker images now stand for and sell Australia.

The distance between Daintree and Dupain is more than one of technological development in a medium, of population growth, or changes in social customs from clothed bush picnics to swimmers on the sand. The whole relation of the figure to the land is imparted in the placement of the figures. It is a landscape of figures and of the development of an identity for the medium and the children of emigrants.

Bibliographical Note

G. C. Bolton, Richard Daintree: A Photographic Memoir (Brisbane: Jacaranda Press in association with the Australian National University, 1965);

John Carroll, Intruders in the Bush: The Australian Quest for Identily (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1982);

Gael Newton, Shades oj Light: Photography and Australia 1839-1988 (Canberra: The Australian National Gallery and Collins Australia, 1988);

Nigel Lendon, 'Richard Daintree', Dictionary oj Australian Artists, ed.Joan Kerr (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992);

Dianne Reilly and Jennifer Carew, Sun Pictures of Victoria: The Fauchery-Daintree Collection, 1858 (South Yarra, Vic: Currey O'Neil Ross on behalf of the Library Council of Victoria, 1983);

Ian Sanker, Queensland in the 1860s: The Photography of Richard Daintree (Brisbane; Queensland Museum Booklet no. 10, 1977);

Peter Quartermaine, 'International Exhibitions and Emigration: The Photographic Enterprise of Richard Daintree, Agent-General for Queensland 1872-6', Journal of Australian Studies, 13, (1983): pp. 40-55

more Essays by Gael Newton AM

For more on Richard Daintree: Australian photographer and geologist

|