Photography: Australia

After Dupain

Gael Newton

Online version of an essay originally published in London Magazine

Vol 35 No 11&12 February/March 1996

|

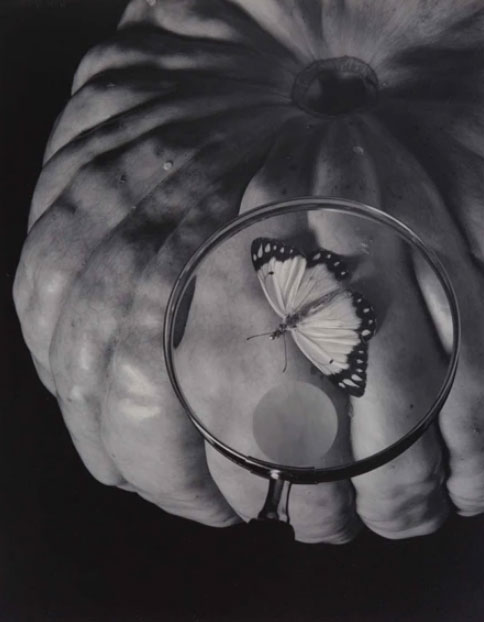

Max Dupain, Pumpkin and Butterfly, 1991

NGA Canberra |

In the last decade of his sixty-year career the photographer Max Dupain was recast in the media as a national treasure whose pictures said something' quintessential' about Australians.

For the most part the focus was on his documentary images of the thirties to fifties. These images seemed to recall a simpler era when values were clearer. Indeed, Australian identity, it is imagined, was less problematic then.

Dupain's fervent belief that his work had to be done on native soil cemented his nationalist aura. He dismissed the need to travel overseas for stimulus, subjects or recognition.

Dupain's architectural work since the fifties and his late still-life studies received less attention.

From the mid-1980s he made a number of still-life photographs with deliberate references to the surrealist modes which had stimulated some of his earliest works in the mid-thirties and forties. It was as if he confronted his own mortality through a series of images made at night and which often presented deathly white flowers.

These images ran counter to the model of Dupain as documenter of Australia. The images also brought together strange combinations of objects and distilled aspects of his work that countered strength with fragility and clear forms with the mystery of sensuous light.

The apotheosis of photography was not something Dupain ever expected to see in his lifetime and he welcomed the attention. But he would have qualified this phenomenon with his belief that photography could never rival the greatness of modern architecture or classical music.

Nevertheless, for a culture that had firmly shut the doors of its art institutions to photography up until the 1970s – 130 years after the medium's arrival on antipodean shores – such honours as were conferred on Dupain represent an extraordinary realignment of national values.

| images copied from original publication |

|

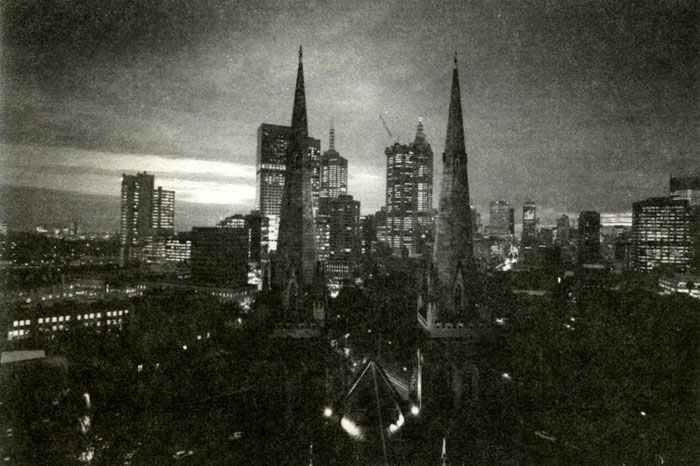

| John Gollings: St.Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne 1992 |

| |

|

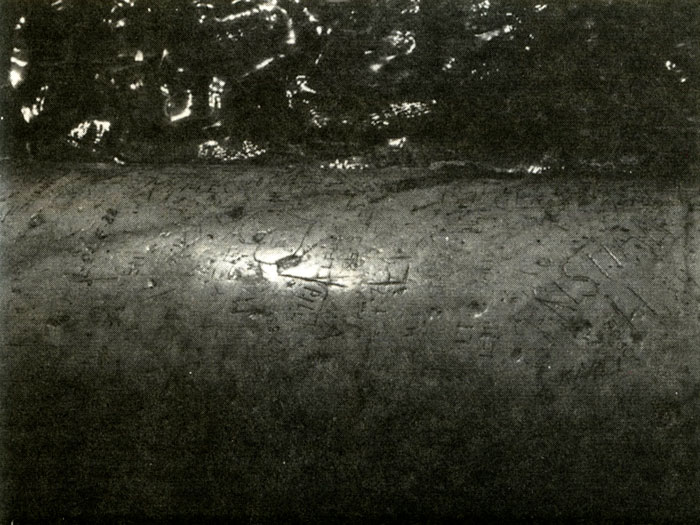

| Wesley Stacey: Names on the Edge, Trevi Fountain Rome 1993 |

Wesley Stacey, some thirty years younger than Dupain, was the first photographer to receive an Australia Council Creative Arts Fellowship in 1992 to continue his landscape photography projects.

Landscape painting in Australia was for a century the prime vehicle for the expression of a national identity. In photography it has been a fitful genre which is surprising given the role which this subject has had in America.

The renowned names of Australian photography have tended to excel in the urban or architectural/industrial fields rather than make great landscape images. The small scale which Australian photographers kept to for landscape has meant that works have rarely attracted much attention in comparison with monumental paintings.

Stacey's earliest landscapes found in the Bush the Biblical symbols of garden and wilderness, culture and nature. The panoramic images in Stacey's new book Signing the Land, meld graffiti and inscriptions from Italy and Australia in search of an almost pantheistic reconciliation between Aboriginal and European heritage.

Curiously the naturalism of Stacey's work remains for many so transparent that its constructions and message is missed.

| image copied from original publication |

|

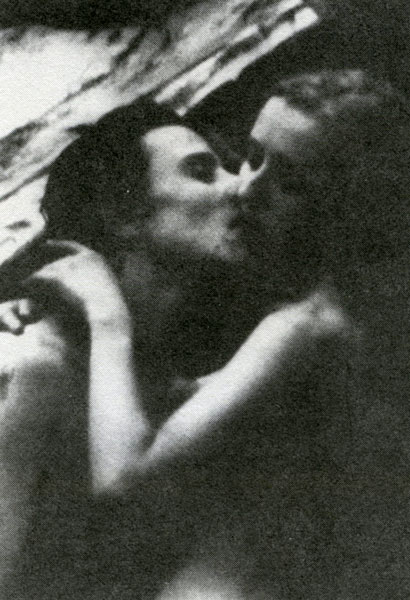

| Bill Henson, untitled |

It was recently announced that the photographer, Bill Henson, whose pictures were featured in London Magazine some years ago will be Australia's contribution to the Venice Biennale in 1995. No photography-based artist has previously been chosen for the Biennale or any such singular representation of the Nation.

Henson is widely regarded as the leading contemporary Australian photography-based artist. His selection for the Biennale is unlikely to cause more than the usual grumbles and hardly any demurs on the basis of whether photography can sustain such a national load.

Henson's work has attracted the attention of the art world since 1981 with his debut installation in Perspecta, the first of a series of biannual surveys of contemporary Australian art.

In Perspecta the artist mounted a quasi-narrative installation of views of crowds alternated with single images of a young boy which suggested a tenuous relation to the style of on-the-run street photography popular at the time with 'documentary' photographers.

However, the work spoke in a European tradition of cinema and literature of the alien modern metropolis.

Henson has strong literary interests and a corresponding respect from major Australian writers such as David Malouf, who provided text for the first monograph on the artist in 1988.

Unlike Dupain, Henson eschews any Australian reference to specifics of place, taste or tradition. Despite the references to other arts, other places, other times so characteristic of his oeuvre, Henson's work has always been true to its own trajectory, although post modernism and the new romanticism in painting has seemed close at times.

Henson's territories have been charted through the 'realisms' offered by photography. He deploys the medium's sensuous transcription of flesh, surfaces and places and draws on documentary style images and other established genres of portrait, travelogue and photojournalism.

These models are transmuted by his complex printmaking to the point where the unreal is equally true and the lines between beauty and ugliness, past and present are confused.

Subjective and objective readings are presented as ambiguous and implacably for the viewer to resolve.

Henson has consistently worked on a large scale. Since the mid 1980s he has also attacked the revered seamless surface of the photograph by assembling images made up of great torn shreds of his mural size prints, attached to backboards which show through.

Increasingly the images are overtly staged apocryphal wastelands. Where earlier sequences had an elegiac note, even when dealing with the feral dwellers of an urban metropolis, his recent works are orchestrations in a higher register.

| images copied from original publication |

|

| Effy Alexakis, Couple |

New directions in Australian photography were made clear in exhibitions such as Australian Photography; the 1980s mounted in 1988 by Helen Ennis, then Curator of Photography at the National Gallery. It showed major shifts not only in the widespread use of large colour or black and white prints but the energy unleashed by a freedom to make images which revelled in artifice and theatricality, connections with the styles of past art and narratives overtly staged rather than captured from the mature'.

There was not a gum tree in sight and landscape as such attracted few as a subject. One of the most significant of changes signaled by such works as were included in Australian Photography; the 1980s was the change in profile of the photographers.

Photographers of non-English speaking and Aboriginal backgrounds have entered the scene since the 80s. Their work has tended to engage more with specifics of living in Australia. However, it was chiefly a new legion of confident and stylish women art photographers who came out in force.

Much of their work has been studio based; tableau and still-life photography writ large but crossbred with the grand traditions of the history picture.

These genres have traditionally been ones which women have felt comfortable with but there the comparison ends. The new works were not genteel but sought centre stage attention. Interestingly, virtually no women have essayed landscape which in this country still bears the burden of providing The National Picture.

So strong has been the women's contingent that it's so-called dominance of art photography was touted in an article titled Game Girls Shoot Back, in the weekend colour supplement of a major newspaper late last year.

Indeed, the success of women photographers has resulted in grumblings from the men that women have led photography astray from the straight and narrow path of documentary, or that 'you've got to be black or a woman to be bought these days'.

Of all the photographers who began work in the seventies none have transformed their work to the extent of Fiona Hall, who completed her education in America at the Visual Studies Workshop and spent time in England in the seventies working at one point with Fay Godwin.

Hall has recently been given the first retrospective at the National Gallery for a younger photographer. She began work in an accomplished, classic seventies style but by the 1980s she had begun to concentrate on photographing tableaux she had assembled herself.

These were wildly mismatched objects which nevertheless when viewed in a photograph recreated famous paintings.

Later images moved back in time and out in space with cosmic references and images inspired by Hieronymus Bosch, Dante, and old alchemical texts (a legacy of her days at the Visual studies workshop and the ideas of Frederick Sommer).

Hall now presents her constructions as sculpture and her most recent show had no photographs at all. Whilst relieved by the wit and inventiveness in many of her assemblages, Fiona Hall's vision is as dark as that of Henson, perhaps more so.

The path of Hall from document to allegory is a phenomenon also visible in a number of prominent artists, particularly women who followed Feminist agendas in the seventies. The continuity of motifs which remain allows for reinterpretation of work previously explained too literally.

|

| Tracey Moffatt, Something More No.1 |

Where any sense of specific Australian location has been dropped from so much contemporary work, Tracey Moffatt (b.1960) a film-maker and photographer of Aboriginal and Irish descent, has gathered together many contemporary strands in her works.

In Something More, a series of 6 colour and 3 black and white mural photographs made in 1989, Moffat seemingly tells a well-worn folktale of a young country girl of mixed race with aspirations who is defeated before she even reaches the Big City. The artist herself takes the lead role appearing as the classic 'woman with the red dress on' in the first frame.

Moffatt's tale of blasted hopes and lives could equally be translated into other post-colonial cultures of the west. The characters are the stock-in-trade of fifties B grade movies set in the Deep south, the orient or other theatres of cultural/racial clash.

The work sweeps into its maw photohistory genres such as Cindy Sherman's pseudo film-stills, high class girlie calendars of Patrick Lichfield and cold erotica of Helmut Newton's White Women.

The set storyline, in which the low-class woman who doesn't know her place and is crushed before she crosses the border to society, would seem to be a curious denial by a young Australian woman on the verge of a promising career of the gains of Feminism and multiculturalism.

Moffatt seeks to confront issues of gender and race as well as those which inhibit the language of the very mediums of her expression.

Moffatt rejects the typing of herself as Aboriginal/photographer/film-maker and is even more distrustful of the naturalism of the camera which was used to such devastating effect through 19th century anthropological photography of Aboriginals.

Robyn Stacey has worked with computer art for ten years and recently returned from America where she was part of an international team using an array of supercomputers. Other works have also appeared which take the form of transparencies on lightboxes.

For younger artists with non-Australian backgrounds the experience of cultural displacement and identity remain important. Those who seem most energized have connected with cultural heritage outside the country.

These include photographers such as Lisa Tomasetti whose work presents anorexic Pietas and Madonnas with girl child, and Hiram To who emigrated from Hong Kong, whose picture Club World sums up much of the dilemmas of relating regions to an ever expanding global homogeneity.

On the whole few would argue that the documentary work that was so to the fore in the seventies and early eighties in Australia, currently lacks the variety and vigour which had made European photography so vital in the last decade.

The importance to an earlier generation of recording and responding to the specific ambience of their time and place has dwindled. In its place stand a highly energetic, committed generation for whom national identity is simply the fact they are here and making art.

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|