Spot on: the art of film stills photography, 1906-2001

Gael Newton AM

Essay originally published in the book

for the 2017 exhibition – Starstruck: Australian Movie Portraits

more details below/ after the essay

|

The Broken Melody set (l-r): Frank Bagnall, Jean Smith, George Heath, Director Ken G Hall filming Diana Du Cane as Ann Brady and Lloyd Hughes as John Ainsworth The Broken Melody 1938 National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Courtesy Cinesound Movietone Productions |

A film star's image is not just his or her films, but the promotion of those films and of the star through pin-ups, public appearances, studio hand-outs and so on, as well as interviews, biographies and coverage in the press of the star's doings and "private life".' Michael Madow, legal scholar, 1987.

By the late 19th century, the top photographic studios worldwide were competing to lure stage stars as clients, with each new print simultaneously publicising the sitter and the photographer. The stars in turn gifted signed copies in the hundreds to their fans, and compiled photo albums of their favourite images.

A leading portrait photographer of the late Victorian, Edwardian and inter-war periods was the dapper H Walter Barnett of the Falk Studio in Sydney, who gained international fame for exclusive portraits of visiting performers, including Sarah Bernhardt on her 1891 Australian tour.

Nineteenth century photographers also made house calls to the theatres, where the cast (in full costume) would pose for promotional shots - the forerunner of'film stills'. It was rather prestigious work, and spreads of images regularly appeared in the pictorial press.

Barnett was always on the lookout for the latest photographic innovations. In 1896 he took time out to partner with Marius Sestier, the marketing agent for the Lumiere brothers of Paris, on the Australian demonstrations of the siblings' Cinematographe movie camera/ projector.

Barnett's flirtation with the new photographic medium would be brief. He departed permanently, as planned, for London in early 1897. Cinematography in Australia went on happily without him.

Many of the first narrative films of the late 1890s and early 1900s were essentially filmed plays made by cinematographers, usually (but not necessarily) with some background in photography. Few films could afford the luxury of a stills photographer on set, so the role often passed to one of the crew.

Studio photographers engaged to make stills for the new medium simply carried on as they had done for theatre productions. Filmmaking on location, however, presented them with unfamiliar challenges.

|

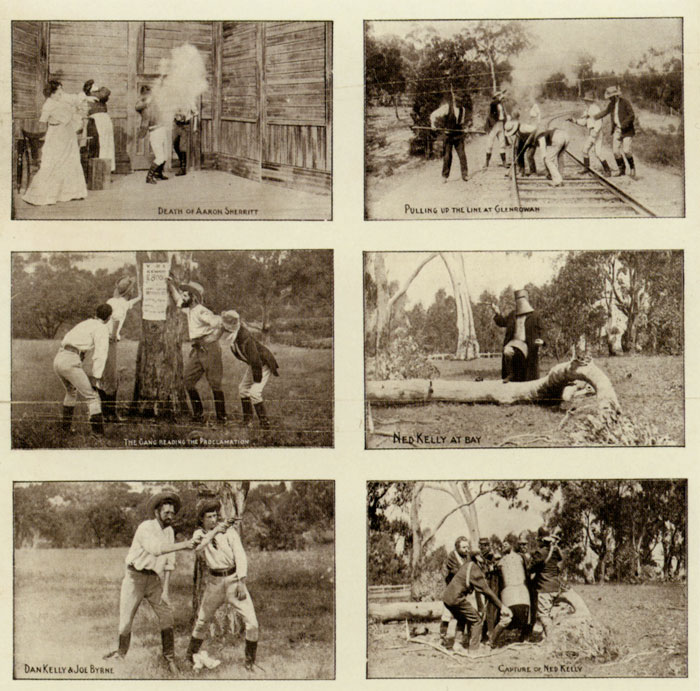

| Frank Mills as Ned Kelly, John Forde as Dan Kelly, Will Coyne as Joe Byrne and Jack Ennis as Steven Hart, poster (detail) The Story of the Kelly Gang 1906 Directed by Charles Tait National Film and Sound Archive of Australia |

Sets were often roofless, open-air stages with crude light control. Action sequences were shot in a variety of locations. The specialist profession of film stills photographer didn't emerge publically in Australia until the 1990s.

The mobility of the new filmed narrative can be seen in the lively mix of indoor and outdoor action stills on the poster for the Tait brothers' pioneering The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), thought to be the world's first full-length, narrative feature film.

The viewer is in the same position as a theatre audience and there are no close-ups. It is clear the cast are holding a pose, rather than captured in action. From this point on, photographers working on film sets would have the challenge of matching the intimate physical and emotional space of the still photograph with the action-packed storytelling of a multi-location filmed narrative.

By World War I, the new profession of cinematographer, and accounts of behind-the-scenes activity on a film set, were subjects arousing public interest. Monte Luke, an actor turned staff photographer and cinematographer for J C Williamson & Co, was one of the first to be profiled (by literary magazine The Lone Hand, in April 1915).

Luke's contemporary Frank Hurley had a more extensive career. He gained international fame for his still and moving images of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911-14, the Shackleton British Polar Expedition of 1914-17, the battlefields of World War I and World War II, and New Guinea in the 1920s. Hurley worked for newspapers, and wrote and directed two melodramatic, narrative feature films: Jungle Woman (1926) and The Hound of the Deep (1926). He was a master of self-promotion and his credit was prominent on any project he undertook.

Hurley's skills led to his recruitment as cinematographer on Cinesound feature films The Squatter's Daughter (1933), The Silence of Dean Maitland (1934), Grandad Rudd (1935), and Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940). He became known in the film industry for his ability to shoot dramatic action and epic, deep-focus outdoor scenes. No bushfire or cavalry charge was too much for Hurley to tackle – he was the master of heroic Australia.

In contrast with the peripatetic Hurley, Sam Hood's adventures took place mainly on the streets of Sydney. Circa 1918, he branched out from studio weddings and portraits and reinvented himself as a prolific events photographer for magazines and papers. Hood also took on a large number of theatrical jobs.

Stills attributed to him of actors in The Sent/mental Bloke (1919) are close-up, and reveal more emotional engagement than his predecessors' work, perhaps due to his experience with press photography. Hood is arguably the first identifiable, substantial film stills photographer in Australia.

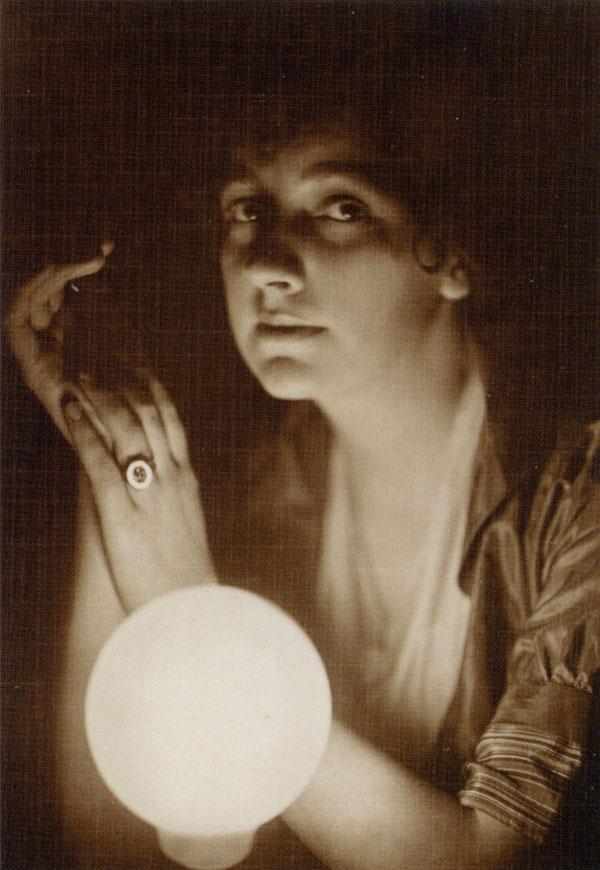

Star portraits and theatre stills by late 19th century studio photographers had provided the models for film promotions. A close relationship between artistic studio photography and film stills is also apparent in the art photography of the early 20th century.

For example, the moody and boldly posed theatrical portraits taken by New Zealand-born studio photographers May and Mina Moore in Sydney and Melbourne were regularly featured in fashionable magazines in the 1910s-20s. A distinctive feature of the sisters' exceptionally accomplished work is their dramatic use of a beam of light on the face of their sitter, set off against plain dark backgrounds.

Variations of this technique, known as 'Rembrandt lighting', had been around for decades and foreshadowed the style known as 'Hollywood lighting' seen in the cinematography and studio portraiture of the 1920s.

Throughout the first decades of filmmaking in Australia there was tension between the static look of staged melodramas and the realism of action filmed on location.

|

| Lottie Lyell as Doreen and Arthur Tauchert as 'the Bloke' by Sam Hood The Sent/menta/ Bloke 1919 Directed by Raymond Longford National Film and Sound Archive of Australia |

One of the first to celebrate location was the gifted musician-turned-documentary cinematographer Franklyn Barrett, who specialised in action and Australian realism. The landscape is as much a star in his silent feature A Girl of the Bush (1921) as the jodhpur-clad lead actress, Vera James.

Realism in settings, acting styles, action sequences, cinematography and stills reached new heights of sophistication during the talkies era of the 1930s-40s. Cinematographer George Heath, who worked with pioneer film producer Ken G Hall, had a long career spanning the 1930s to the 1950s - a testament to the consolidation of the industry. He typified the new professionalism of cinematographers in the talkies era.

Heath had been to America and understood the new Hollywood-style atmospheric lighting that producer Hall wanted, in preference to Hurley's sharp depth of field and bright lighting. When interviewed by the Western Mail in 1937, Heath clearly articulated both the cinematographer's and the stills photographer's task, noting that they' must faithfully portray the varying moods of the story as the director reveals them through the artists and the atmosphere he has created on the set'.

He might well have added that the stills photographer needs to capture tender moments on set, despite the presence of crowds of people, equipment, and hot lights.

|

Gwen Burroughs c.1912 by May and Mina Moore

May and Mina Moore collection State Library of Victoria |

In the new century, studio photography and cinematography retained their mutually influential relationship. During the 1930s in particular, studio portraitists adopted 'Hollywood lighting'styles and poses for their regular customers, as well as any actual stars they had as sitters.

One of the finest Australian-born exponents of glamour portraiture worthy of a film set was Melbourne's Athol Shmith. Best known for his portraits of theatrical performers, fashion models, brides and grooms, and Melbourne socialites, Shmith conducted his portrait shoots like a director, cajoling'star' performances out of his sitters. He received several film publicity portrait commissions, beginning with Charles Chauvel's Heritage (1935), and closing with American director Stanley Kramer's On the Beach (1959). Like Walter Barnett, Shmith was at home in the theatrical world.

Other top 1930s studio portraitists, such as Harold Cazneaux and the young modernist Max Dupain, both in Sydney, also took glamour portraits in the latest styles, with Hollywood overtones, but largely avoided the film world.

Damien Parer was possibly the most experienced professional studio photographer to switch to cinematography. He had roles on films including Forty Thousand Horsemen (1935) and This Place Australia (1939).

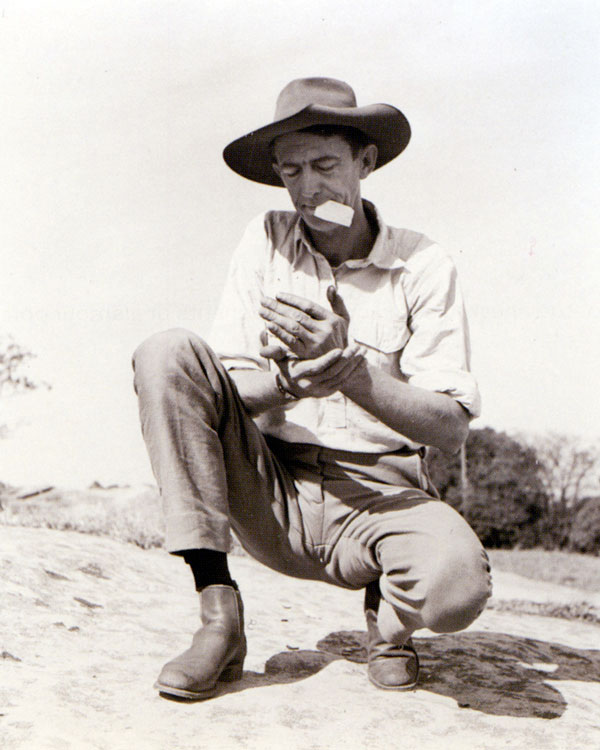

During World War II and in the post-war years, rousing, jingoistic films celebrated the Australian outback, featuring characters - such as those played by Chips Rafferty - who projected the imagined toughness and self-reliance of pioneer settlers.

Rafferty's image (via stills, as well as his films) reached iconic status at home, and was a prominent emblem of the 'Australia' brand abroad. During this period, big productions with international aspirations demanded promotional images of a high order, and stills photographers up for the rigours of filming in remote locations.

In the 1940s, new arrivals, including cinematographer Carl Kayser - a German refugee who came to work in Australia during the war - and assistant cameraman Axel Poignant - an Anglo-Swedish immigrant - shared their expertise with locals. Poignant later worked as a cinematographer with the Commonwealth Film Unit, although he remains best-known as a documentary and natural history photographer. There were a number of international film collaborations made in Australia in that decade, including The Overlanders in 1946.

Queensland-born director Charles Chauvel's nationalistic spirit and love of the Australian landscape suited the times; he went to great lengths to find locations for his films that showcased the majesty of the land. Chauvel's 1949 pioneer-settler epic Sons of Matthew was a case in point, and a rugged exercise for cast and crew.

Extensive publicity about the making of the film led Angus and Robertson to quickly publish How they made Sons of Matthew. Written by scriptwriter Maxwell Dunn, it is probably the first revelation of behind-the-scenes film making in Australia, although no stills photographer was credited.

For his film Jedda (1955), Chauvel, with British photographer Phil Pike (later well known as an Australian cinematographer) and cameraman Carl Kayser in tow, scoured central Australia for suitable locations and Indigenous cast members. Jedda was the first Australian feature shot using colour film, and it stimulated popular interest in central Australia and Aboriginal culture. The film was made in the lead-up to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, with Aboriginal iconography used in the concurrent international promotion of the Games. Jedda was perhaps the first Australian-produced film to have merchandise of various kinds, including a colour brochure, Eve in Ebony: The Story of'Jedda' (1954), featuring Phil Pike's portraits of the stars. These portraits were issued as fine art prints and used on a range of Brownie Downing ceramics.

|

| Chips Rafferty c. 1950 by Max Dupain National Portrait Gallery Purchased with funds provided by Timothy Fairfax AC 2003 |

The 1960s brought a move away from the grand rhetoric of pastoral pioneers and monumental landscapes to offbeat, urban Australian stories. One of the first efforts was Clay (1965) - with its poetic, European arthouse quality - by migrant Italian film director and professional portrait photographer Giorgio Mangiamele.

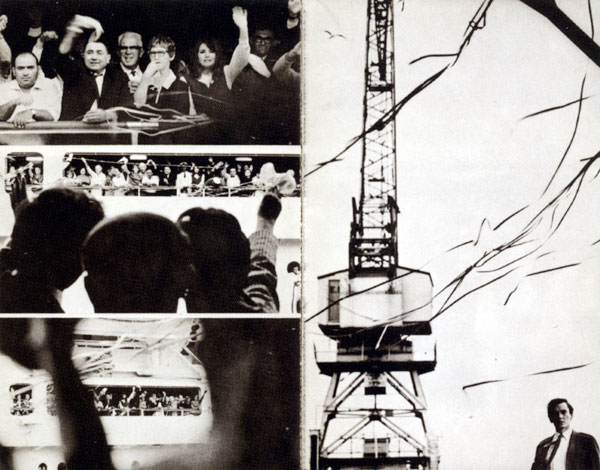

A few years later, in 1969, bohemian director Tim Burstall made Two Thousand Weeks, an arthouse film about a thirty-something writer having a mid-life crisis. Two Thousand Weeks, which, as one review proclaimed, had 'No Outback, No Koalas or'Roos', is held as the flag-raising project of the Australian cinema renaissance in the 1970s.

It also marked a new appreciation of film stills, with Burstall and producer Patrick Ryan seeking out like-minded creative artists to work on the film. They chose Mark Strizic, a prominent Melbourne art, architectural and portrait photographer, as the unit stills photographer. Strizic had a distinctive graphic style, and his images were often seen through an out-of-focus foreground or background, or against the light. These techniques were deployed as an expressive tool for interpreting the subject, and were effectively applied to the film stills for Two Thousand Weeks.

|

Crew filming Michael Pate as Shane Sons of Matthew 1949

Directed by Charles Chauvel National Film and Sound Archive of Australia

Courtesy Ric Chauvel Carlsson |

Strizic also co-designed a small photo novel; it featured dramatic high-contrast colour and black-and-white stills shot by Strizic and cinematographer Robin Copping, accompanying some of the film dialogue.

Published by Sun Books, Two Thousand Weeks is probably the first occasion when credited film stills take on an aesthetic life of their own in a publication. As declared on the title page, the book was 'dedicated to the future of the Australian Film Industry'.

|

| Robin Copping (top left image) and Mark Strizic (all other images), pages 160-161 from Two Thousand Weeks: The Book of the Film by Tim Burstall and Patrick Ryan, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1968 National Library of Australia Courtesy Tim Burstall and Patrick Ryan Estate |

Stills from many of the feature films shot during the 1970s and 1980s employ the offbeat ambiguity of the new 'personal' documentary art photography of the period, which sought subjects in urban subcultures. The style of Carol Jerrems, an art photographer and filmmaker who worked on director Esben Storm's In Search of Anna (1979), shares qualities of mood and framing with Strizic's work of a decade earlier.

During this period stills photographers were often sought out by, or chose to work with, certain directors. There was a new kind of film-literate photographer emerging, such as photojournalist Robert McFarlane, for whom European films' use of black-and-white film 'was a visual language I instantly understood'.

Perhaps stills photographers were beginning to be recognised as people who could contribute an individual creativity to the totality of a film, as a record of its production, promotion and interpretation.

McFarlane brought his documentary photographer's eye to his work, treating film stills like street photography. His first commission, in 1981, was as unit stills photographer for director John Duigan's Winter of Our Dreams. His use of a quiet 35mm Leica camera enabled him to capture an iconic shot of Duigan on set in discussion with lead, Judy Davis.

McFarlane's interest in film sets was also influenced by the body of work produced by the eight Magnum photojournalists invited on set for the 1961 John Huston film The Misfits. The output of this now legendary photographic project was widely published at the time, as the film was sadly to be the last roles of lead actors Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe.

The Magnum photographers' role on The Misfits has been the subject of a number of recent books, and has contributed significantly to the public understanding of what a set is - as a story in itself - as well as further revealing the creative potential of stills photography.

In the 1980s, postmodernism in the arts heralded a rebellion against the idea that social or philosophical truths could only be found in either realism or abstraction. Artifice, kitsch and hyper-real effects became a way to address contemporary issues, including colonial and post-colonial history, identity, race and gender. The range of practitioners also broadened, with more diversity in ethnicity and gender evident.

The work of photo-media artists such as Robyn Stacey, Anne Zahalka and photographer-filmmaker Tracey Moffatt, for instance, has the look of lush movie sets but with contemporary perspectives.

Female film directors and producers emerged in the 1980s out of the new tertiary training schools, and (as with stills photography), their rise was rapid. Producer Margaret Fink and recent graduate director Gillian Armstrong's 1979 adaptation of Miles Franklin's My Brilliant Career became the first feature film directed by an Australian woman to be released in mainstream cinemas since 1933.

|

| Judy Davis and John Duigan between takes by Robert McFarlane Winter of Our Dreams 1981 Directed by John Duigan National Portrait Gallery Purchased 2017 |

The period between the 1950s and early 1970s saw many women working in film production, albeit mostly in documentaries and short narrative films. Their ranks produced a historian of the medium in producer-director Joan Long, who wrote scripts for documentaries on early film in Australia - The Pictures That Moved (1968) and The Passionate Industry (1971) - both published in book form in 1982.

In the same year, Jenni Mather and Barbara Hall published a parallel history of Australian women photographers from 1840 to 1960. In 1986 Joyce Agee curated Stills Alive, an exhibition of photographs from vintage and contemporary films from 1900 to 1983.

More recently, an exhibition of behind-the-scenes stills, From a Sunday Too Far Away, curated by Melissa Juhanson, celebrated the 40th anniversary of the South Australian Film Corporation. In the same year, 2012, cinematographer and film scholar Martha Ansara produced a richly detailed photobook The Shadowcatchers: A History of Cinematography in Australia. It is arguably the first publication to do justice to the art of film stills.

|

Judy Davis as Sybylla and Sam Neill as Harry by David Kynoch

My Brilliant Career1979 Directed by Gillian Armstrong

National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Courtesy Margaret Fink |

Surreal fantasy was also a hallmark of the 1980s, with movies such as Mad Max (1979) and Mad Max 2 (1981). Under Wendy Dickson's art direction, Ray Lawrence's Bliss (1985), based on the Peter Carey novel of the same name, was described by critic Paul Byrnes as a 'leap away from naturalism and the historical realism of the "new wave" film makers of the 1970s, towards the post-modernism of the 1990s'.

The 1990s saw an increasing awareness of stills photography as an art form in its own right. In 1994, when photographer Grant Matthews exhibited Polaroids from his stills for Jane Campion's The Piano (1993) at Stills, a commercial photo gallery in Sydney, the gallery asked for a limited edition of the prints to be produced, in the manner of those of its stable of art photographers.

|

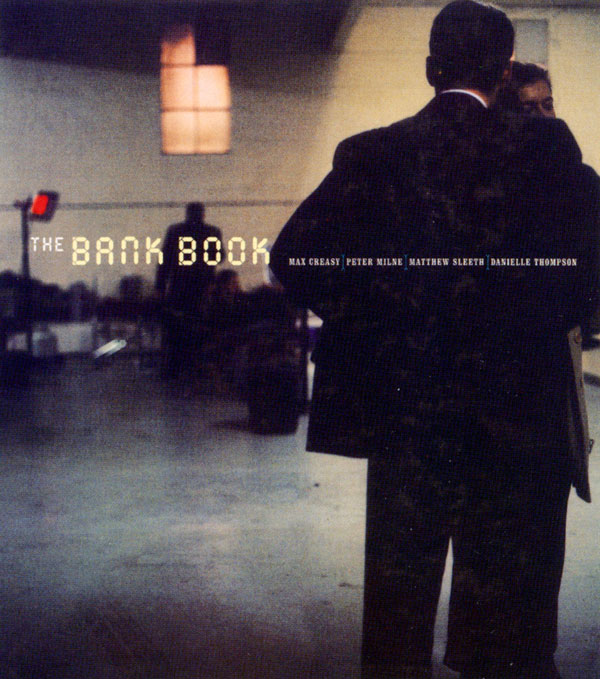

| Matthew Sleeth (cover image), The Bank Book: Photographs by Max Creasy, Peter Milne, Matthew Sleeth and Danielle Thompson, M.33. Melbourne, 2001 Courtesy Helen Frajman |

The most independent presentation in the history of film stills' journey to autonomy is probably The Bank Book (2001) by gallerist and agent Helen Frajman of the M.33 organisation in Melbourne. The book's genesis was the invitation to young art photographers Max Creasy, Peter Milne, Matthew Sleeth and Danielle Thompson to attend the set of the Robert Connolly film The Bank, shot in Melbourne in July 2001.

In art historian Daniel Palmer's introduction to The Bank Book he proposes a radical view of the film still: 'an expansion of the genre of "stills photography", liberated from the constraints of the publicity department, these images extend the space of the film beyond the screenplay or director's control... we do not need to have seen Robert Connolly's film to appreciate these photographs'.

But it is better if we do see the films, read the books and appreciate that, like Gothic cathedrals, films in all their reach and associated genres, such as stills, are towering cultural edifices built by so many artists and artisans

Gael Newton AM

for more on the National Portrait Gallery exhibition: Starstruck - click here.

The essays as listed in the exhibition book:

Headshots: the actor's business card by Karen Vickery

Spot on: the art of film stills photography, 1906-2001 by Gael Newton

A journey through time by Meg Labrum

The still image: documenting Australian filmmaking by Jennifer Coombes

Film portraiture: perception or reality? by Dr Jennifer Gall

Stealth ninja: the feature film stills photographer by Penelope Grist

For the National Portrait Gallery bookshop - click here.

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|