George Silk photographer

Gael Newton

Originally published in Art & Australia

vol 32 No 1 2000

|

|

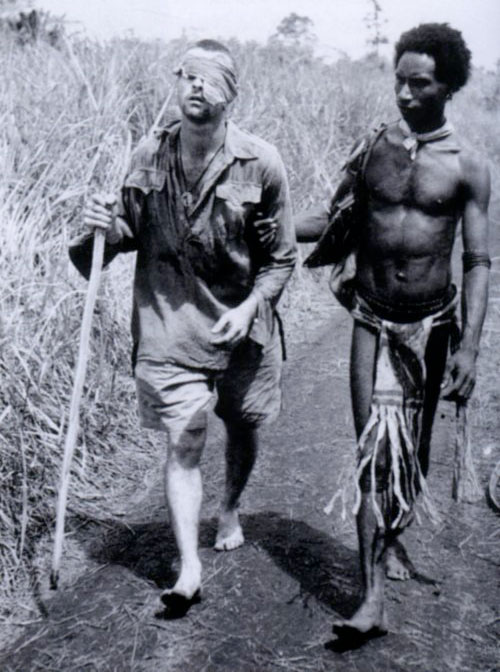

Blind soldier, the well-known image by George Silk, 'official photographer with the Department of Information, was first published in Life magazine on 8 March 1943.1

Silk, a New Zealand national, had already covered Australian campaigns in the Middle East, North Africa and Greece, as well as assignments in New Zealand, before joining troops in New Guinea in r942. Not long after taking Blind soldier, Silk left New Guinea, never to return.

After a period of ill health back in Sydney, Silk resigned from the Department of Information. He accepted an invitation from Life editor Wilson Hicks to become a war correspondent, and worked as a staff photographer for the magazine until 1972.

By the mid-1960s Silk had an international reputation as a photojournalist noted for his innovative action, outdoor and sports photography, particularly in regard to his colour work. Yet his postwar career is not well known in Australia today.

Though a seemingly straightforward photograph taken in swift response to a scene, Silk's image of Private George C. Whittington and the Papuan orderly Raphael Oimbari reflected the growing publicity in Australia in 1942 surrounding the heroic role of the natives in helping Australian troops in New Guinea.

This was revived in 1992 for the fiftieth anniversary of the Kokoda Campaign.2 The photograph, however, has a more universal appeal and is underpinned by the familiar Christian iconography of the Good Samaritan.3

It is perhaps this broader reading of the image that appealed to Wilson Hicks. (The image was reputedly later used as the basis of a United States war-bonds-drive poster.)

Hicks's faith in employing Silk was based on two images: the New Guinea picture, and an image of a cow titled 'Spring' in New Zealand, 1942, which was published in the 'Pictures to the Editor' section of Li/eon 1 February 1943.

Hicks's intuition was justified by Silk's subsequent war reportage for the magazine in the Pacific, Europe and Japan.

Silk was twenty-two at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Already a skilled photographer, he had not worked as a professional when he took the initiative of quitting New Zealand for Sydney to seek appointment as a war photographer. He presented his portfolio of dramatic skiing and sailing pictures to the Prime Minister's Office in Canberra, and was immediately recruited as an official photographer.4

Born in 1916 and raised in Auckland, Silk was uninterested in schoolwork but serious about his hobbies - photography, model aeroplanes, climbing, fishing, sailing and later, skiing and motorcycles. He dreamed of going to the Poles and of climbing Mount Everest.

|

| EDWARD CRANSTONE, Portrait of George Silk, (Sydney), 1939, gelatin silver photograph, collection of the artist. Reproduced courtesy the Australian War Memorial, Canberra (negative number 001390/31). |

|

GEORGE SILK, Blind soldier (Papuan native leading blinded Australian infantryman away from Buna front), r943, (detail), gelatin silver photograph, collection of the artist. Appeared in Life, 8 March 1943, p. 36.

Reproduced courtesy the Australian War Memorial, Canberra (negative number 014028). |

After leaving school at fourteen, he worked for two years on a dairy farm. When he returned to Auckland he got a job in a shop that had the first New Zealand agency for the modern European small-format Rolleiflex, Leica and Agfa 35 mm cameras.

The small-format cameras launched in Germany in the 1920s were the instruments of choice for the new generation. They were better suited to sports, action and spontaneous reportage than the older style, large-format stand or press cameras.

The albums that survive of Silk's first efforts at photography show a consistent experimentation with light effects and unusual angles.

For instance, he positioned himself beneath overhangs in order to capture his friends skiing over the top of him.

D. G. Begg, the owner of the camera store, encouraged Silk to experiment with the new cameras and to make prints in the darkroom for window displays.

At the end of the war, Silk was the first to cover the extent of the devastation of the atomic bomb in Japan.

He remained in the East to cover the Allied occupation and the famine in China, and produced notable stories along the way. In 1947 he moved to New York and in 1952 to California. |

|

|

| |

GEORGE SILK, 'Spring' in New Zealand, 1942, gelatin silver photograph, collection of the artist.

Appeared in 'Pictures to the Editor', Life, 1 February 1943, p. 100. Reproduced courtesy Timelnc. |

Assignments on the Grenfell Mission Boats in Labrador and along the Pacific Coast of Vancouver Island, and landing on Ice Island T3, 145 kilometres from the North Pole, were helping him to realise his boyhood dreams of rugged outdoor adventures.

It was inevitable that Silk would cover sports but he was not to make a real mark until the late 1950s. He covered the British Empire Games in Vancouver in r954 and, in the following year, his dramatic action shot of a man felling a tree in New Zealand was included in Edward Steichen's 'Family of Man' exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In 1956 in Melbourne he covered his first Olympics, but it was at the Pan American Games in Mexico City (also in 1956) that Silk first made startlingly different pictures. There he used a panoramic camera which he rotated vertically to catch the pole vaulters.

His sports pictures began to appear regularly and as a result he was summoned to the Life headquarters in New York. To avoid team sports, which he disliked, Silk set out in 1958 for Idaho's Sun Valley to do a consciously different skiing story and, with the help of a fellow skier, arrived at the idea of attaching the camera directly to his ski. Many shots failed but the successful ones were exciting.

GEORGE SILK, Hammer thrower, Olympic tryouts, Palo Alto, 2960, gelatin silver photograph, collection of the artist. Reproduced courtesy Time Inc.

Silk's next innovation came in 1959 while he was doing a story on the Kentucky Derby, in which new pictorial (as opposed to technical) use was made of the heavy and cumbersome race-finish cameras of the day. At Palo Alto, California, Silk used a specially modified portable slit-camera to cover the trials of the United States track team for the 1960 Olympics.

Life ran a major story juxtaposing Silk's distorted images tracing the athletes' movements with the usual documentary shots. This treatment rendered the athletes as cartoon superheroes, involving readers in the intense private moments as they strained in their efforts to be picked for the team.

GEORGE SILK, Halloween, i960, dye-transfer colour photograph, collection of the artist.

Appeared in 'Spectacle of spooks to be wary of on Halloween', Life, 31 October i960, pp. 52-3. Reproduced courtesy Time Inc

Also in i960, Silk explored the distortions of the slit-camera with colour film. He arranged to have children dress up in Halloween costumes and run and jump in front of the camera. George Hunt, the assistant managing editor at Life, designed a dramatic, intensely colourful layout which was markedly different from the convetional narrative layouts for photo-essays. Silk's colour work would earn him considerable acclaim throughout the decade.

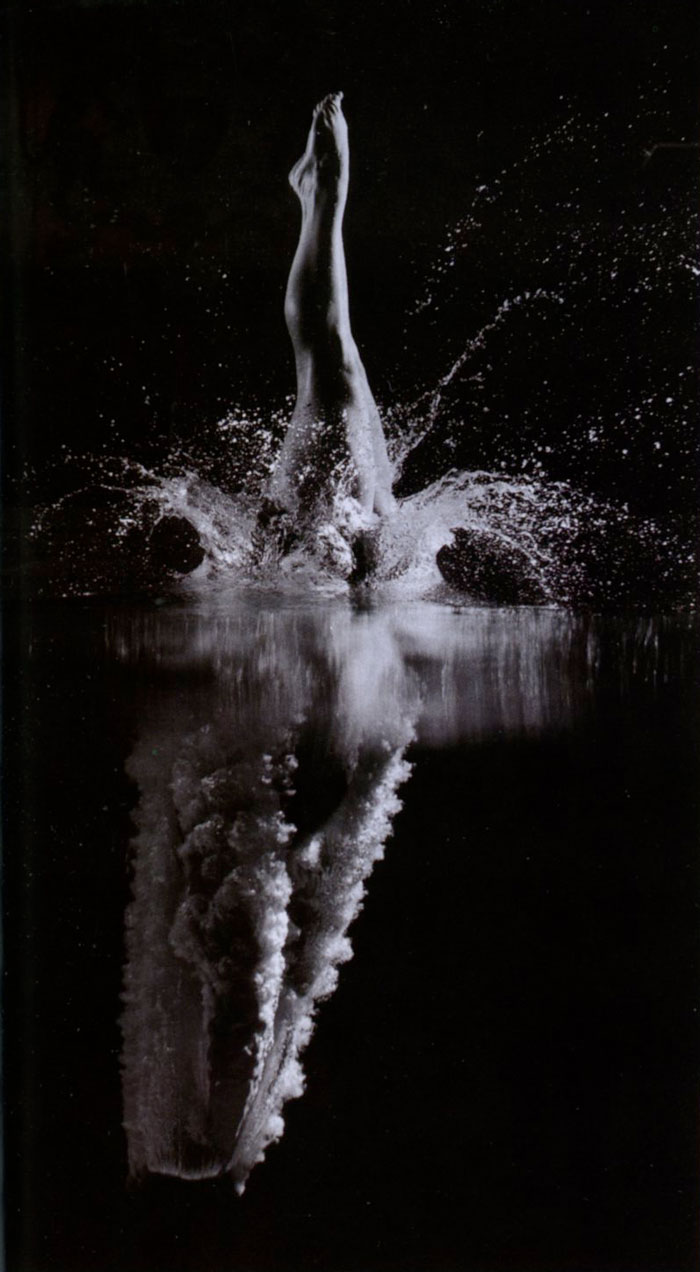

Another assignment resulted in Silk's captivating images of the young champion high-diver Cathy Flicker. Silk lowered the water level of the indoor pool at Princeton University so that a side window was midway above the waterline, enabling him to show her knife-like entry into the water and emergence in a cocoon of plume.

With Perfect 10 point landing, 1962, the viewer goes along for the ride, diving through space as effortlessly as a bird.

GEORGE SILK, Perfect 10 point landing, 1962, gelatin silver photograph, collection of the artist.

Appeared in Life, 20 April 1962, pp. 88-9. Reproduced courtesy Time Inc.

Silk was developing an interest in nature photography at this time. In 1960 he spent four months travelling 11,000 miles across the United States for a major essay on wild creatures. People often responded to Silk's images with amazement ('How did he do that?'), because he seemed too close to the subject not to be noticed, or too close to the action not to be in danger.

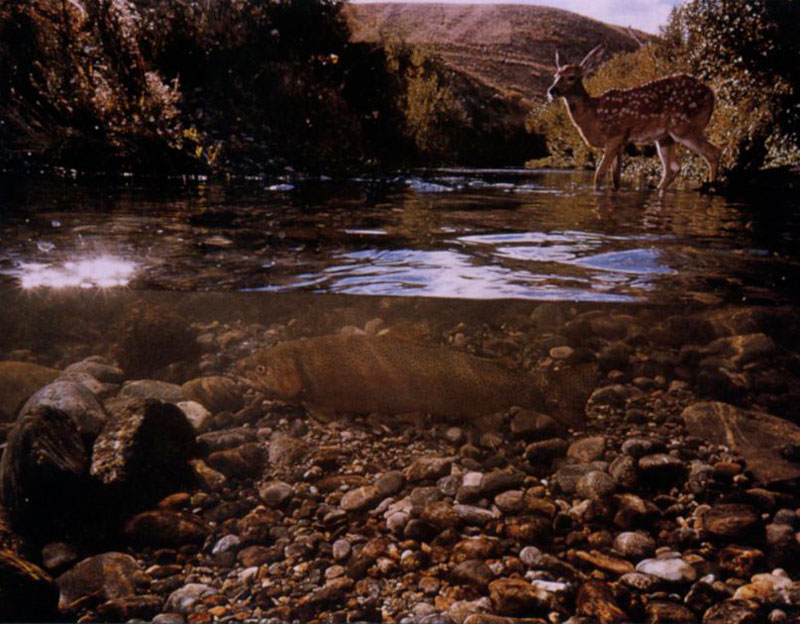

GEORGE SILK, Fawn and rainbow trout, tributary of the Madison River, Montana, 1962,

dye-transfer colour photograph printed later, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Reproduced courtesy Timelnc.

This was the case with a picture of trout in Idaho. Silk set up a camera in a glass box half-in and half-out of a trout stream, then waited for over a week, hidden some distance away, with a remote shutter-release to trigger the exposure at the critical moment.

Silk was an experienced fisherman and, knowing how spawning trout behave, had rearranged some rocks to make the water flow in a way that was enticing to them. He also knew that a fawn came to drink at the stream, and that it was just a matter of time before both animals appeared simultaneously.

The resulting image of trout and fawn suggests a fantasy where the viewer is able to return to the intimacy of the natural world before the loss of Eden.5

By the time he came to shoot the America's Cup trials off Newport, Rhode Island in 1962, Silk was in creative and technical overdrive.6 His expertise as a yachtsman was an entree to the skippers, who allowed him to make daring shots from mastheads or hanging from the sides of their boats.

His brilliant colour images of the sail of Nefertiti behind a swell and the hulls of contenders Gretel and Weatherly racing past each other were almost like abstractions. The images thrilled the editors, who were keen to bring race coverage to a wider audience than 'yachties'.

|

|

|

| GEORGE SILK, Twin hulls, Gretel and Weatherly, off Newport, America's Cup trials, 1962, dye-transfer colour photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Reproduced courtesy Time Inc. |

|

GEORGE SILK, Nefertitibehind a swell, 1962, dye-transfer colour photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Appeared in 'Cutting the waves for a classic Cup', Life, 24 August 1962, pp. 60-1. Reproduced courtesy Timelnc. |

Throughout the 1960s recognition for Silk's innovative sports photography came from his peers: he was named 'Magazine Photographer of the Year' successively in i960 and 1964, and received a number of other awards. His works were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and in a major exhibition in 1967, 'Man in Sport', at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Later, in 1992, he was honoured as the Master of Photography at the prestigious photojournalism festival Visa Pour L'Image in Perpignan, France. In common with most photojournalists, however, Silk considered that being published in mass circulation magazines was more democratic and better value economically than being represented in exhibitions.

Working for Life had suited Silk, and its administrative support relieved him of the paperwork associated with being a freelancer. He enjoyed nearly absolute freedom and independence with a seldom questioned expense account. He was good at providing images which the editors wanted and which also challenged his need to be creative.

The closing of Life as a weekly in 1972 marked the end of a period in which the media had been dominated by picture magazines. Silk continued as a freelance photojournalist doing major stories, particularly on the environment.

Asked several times by interviewers over the years whether his work was art, or to make profound statements on the meaning of his images, Silk asserted that it was great to be paid for what you love to do.

But this simple equation of a career in photography as a lifestyle option is qualified by Silk's actions in regard to posterity. Silk clearly recognised the value of his work, and in the 1980s organised the printing of many images in the permanent dye-transfer colour process.

With the era of the picture magazines behind us, the archives of many photojournalists such as George Silk are being brought before the public and subjected to closer scrutiny. This will enable a reinterpretation of their significance, not only in terms of the reception of their images and the complex relationship between client, editor, picture editor and photographer, but also as makers of images which have meaning in a cultural context. |

|

|

| |

GEORGE SILK, Gunda Larhking, Swedish high jumper, Olympic Games, Melbourne 1956,1956, gelatin silver photograph, collection of the artist. Reproduced courtesy Time Inc. |

- Reproduced as Blind Soldier: Papuan Native leads an Australian infantryman away from Bunafrontin 'The Week's Events', Life, 8 March r943, p. 36. Silk took the image at Buna on Christmas Day 2942. The image rights remain the property of the Australian Government and George Silk's war negatives are held by the Australian War Memorial, Canberra. Blind soldierus the frontispiece of The War in New Guinea: Official War Photographs of the Battle for Australia, F. H. Johnston, Sydney, (1943). This booklet is illustrated with Silk's photographs and acknowledges his importance as a photographer.

- In 2993 Silk described taking the single negative with his Rolleiflex, see p. 179 of the interview 'George Silk' published by John Loengard in his book, Life Photographers: What They Saw, Bullfinch Press, New York, r 998, pp. 274-93. See also Neil McDonald, War Cameraman: The Story ofDamien Parer, Lothian Books, Melbourne, 1994.

- See Neil McDonald & Peter Brune, 200 Shots: Damien Parer and George Silk and the Australians at War in New Guinea, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2998; and Angels of War: Papua New Guinea and the Experience of War, a 2982 documentary film by Hank Nelson, Andrew Pike and Gavan Daws. Blind soldier formed the basis of a memorial sculpture by Helena Anderson, which was rededicated in r 99 2 when it was moved to the Canberra Services Club, Manuka, ACT. Oimbari, who was brought to Canberra to attend, was awarded an OBE in 2993. He is now deceased. The caption in Life accentuated the caritas aspect as well as race relations between the indigenous people and the soldiers.

- Silk's skiing images from a September visit to New Zealand were published in Parade, the military magazine for the Middle East, in 1942. These images were the same or similar to those he showed to the Australian prime minister. Material sighted by the author in the photographer's home at Westport in r 999.

- A variant of the illustrated version (with two trout) was published as a double-page spread in 'Wild creatures of America', Life (special double issue titled Our Splendid Outdoors), 22 December 1962, pp. 22-50.

- See 'Cutting the waves for a classic Cup', Life, 24 August 2962, pp. 48-62. Silk wrote a 'A wild, gutsy race' for the essay, pp. 62 a-b. As a staff photographer for Life, the copyright and the major part of Silk's negative and colour transparency archive made in their employ is held and administered by Time Inc. The Life Gallery sells prints of Silk's images. Staff photographers are supported when opportunities for personal exhibitions or publications arise.

The exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia was A Sydney 2000 Olympic Arts Festival exhibition.

Gael Newton AM was Senior Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|