Exhibition Introductions / biographical details / exhibition prints & checklist /// for more on Axel Poignant

| |

|

An online version of the catalogue

for theretrospective exhibition of the work of Axel Poignant

The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 1982

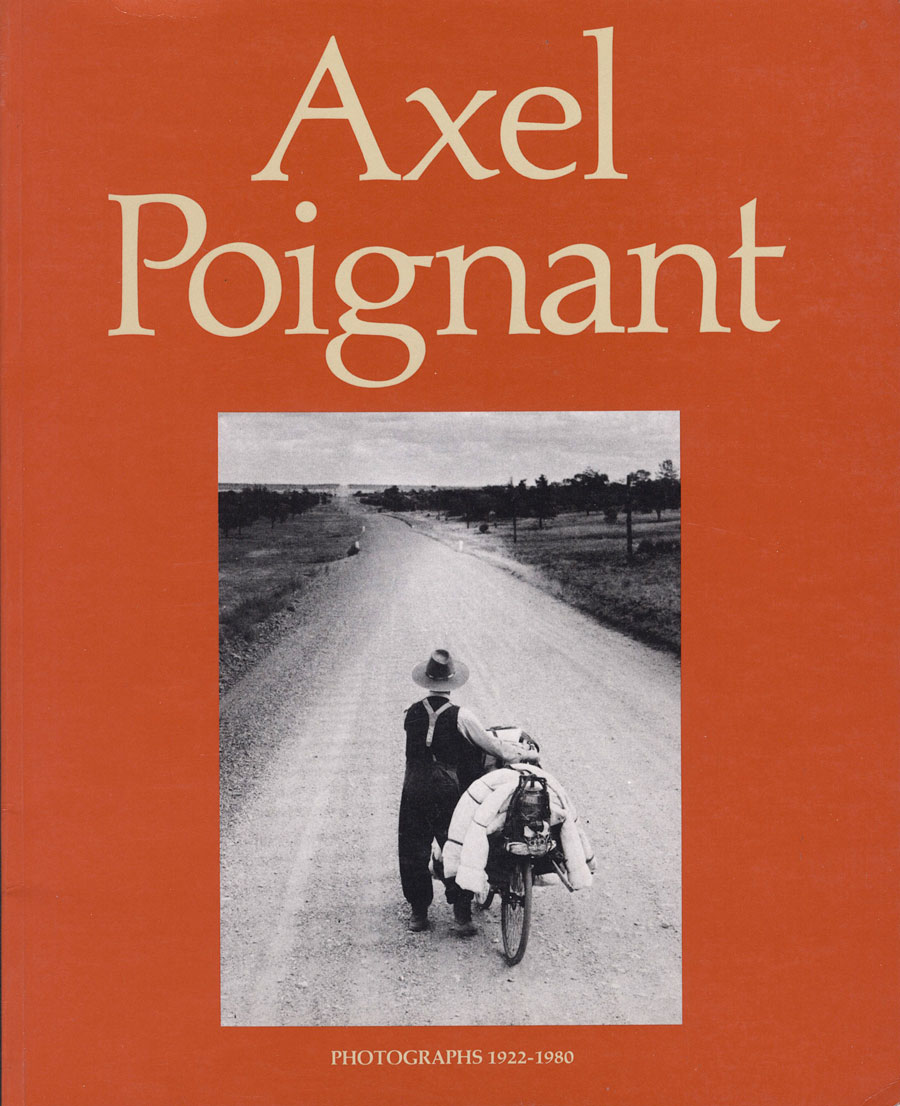

Cover image:

Swagman on the road to Wilcannia, 1953/4 (cat 74) |

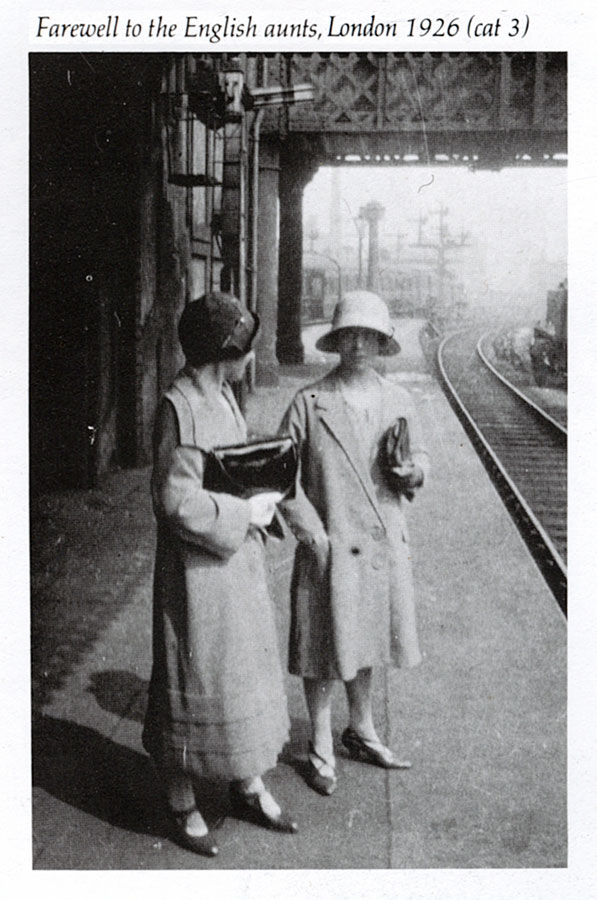

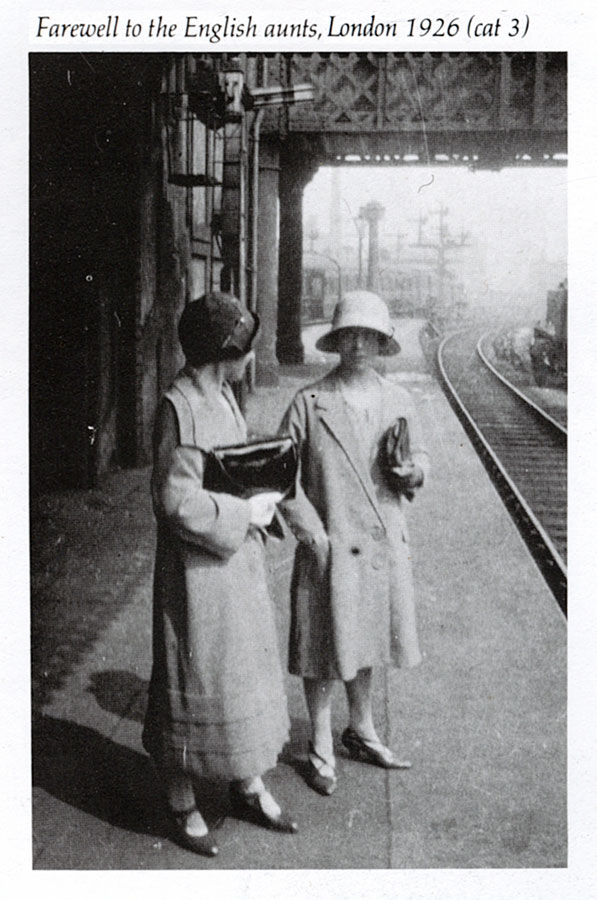

In May 1926 Axel Poignant bade farewell to his English aunts at a London railway station (cat 3). He was en route to Liverpool to join other young emigrants aboard the Pakeha, bound for Sydney, New South Wales.

Poignant had left Sweden over three months earlier at the suggestion of his Swedish aunt, Maria, then living in Harrogate, England, who had drawn his attention to an advertisement for assisted passage to'Sunny New South Wales'.

The scheme sought British youths to undertake basic training in Australia for jobs on the land. Although born in England, his Anglo-Swedish parentage caused some delays in his acceptance. Whilst waiting to depart Poignant practised with his newly acquired vest-pocket camera with the aid of Kodak How to do it pamphlets, one of which inspired a sensitive silhouette study of his kindly aunt (cat 2).

Australia appealed to the young migrant as a land of adventure and wilderness. He knew little of the country except that it had been a penal colony, and had its own 'wild' Aborigines whose artifacts he had seen in display cases at school.

Although he was bound for New South Wales he hoped to reach Tasmania because 'from the map it appeared to have more rivers and he wouldn't die of thirst'. His Swedish grandmother, however, was more hopeful and included a dinner suit in one of his trunks. |

|

|

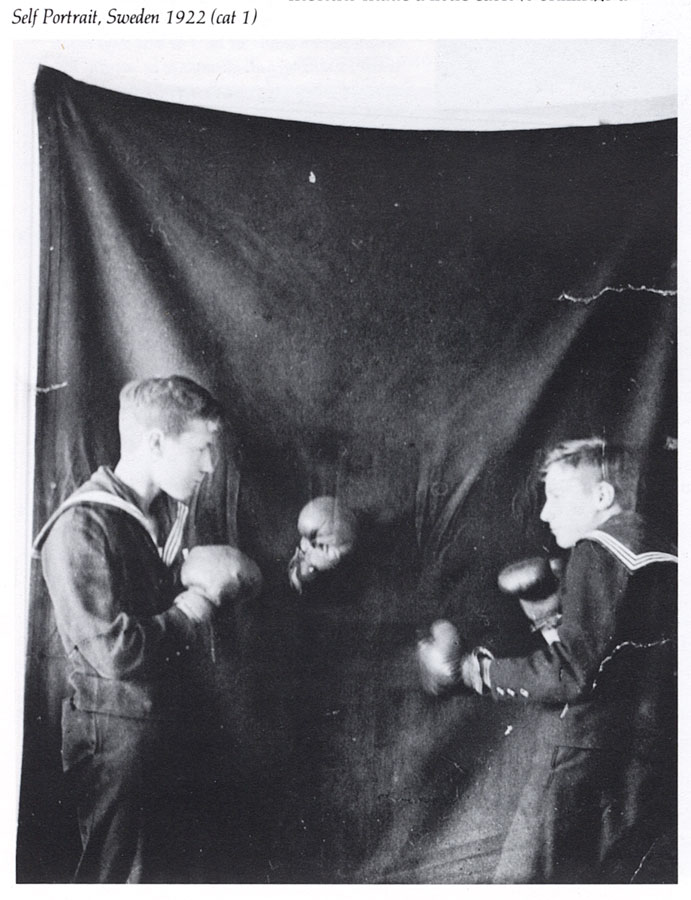

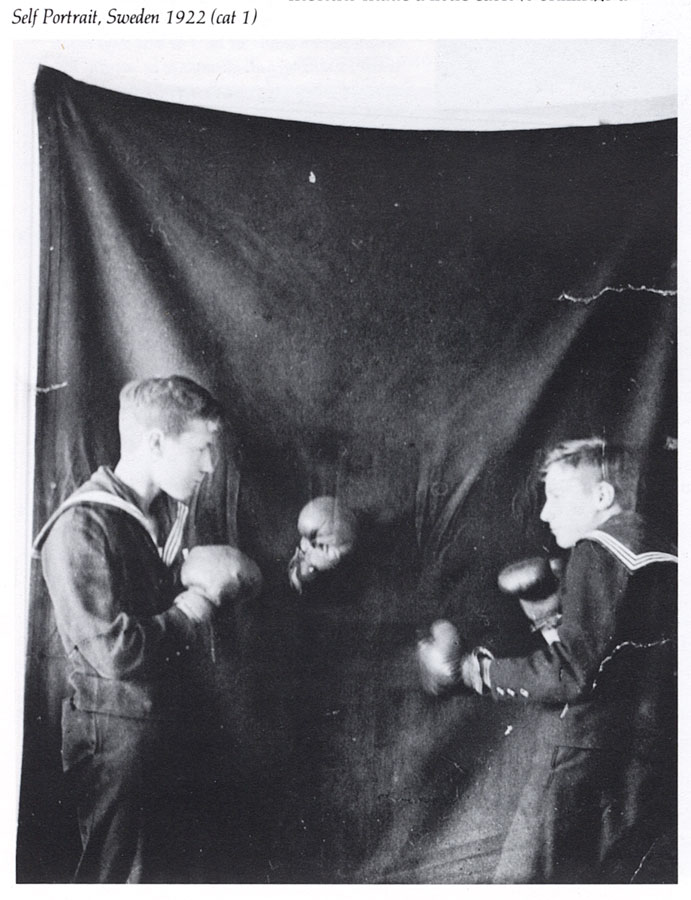

Poignant had already developed a preference for the outdoors. As a boy, he belonged to the sea scouts, and in 1922 he spent a year as a sea cadet aboard a Swedish windjammer, followed by a period working for the taxation department, assessing timber resources in the isolated forests of northern Sweden. Then for several years he was employed as a clerk in his father's office. The boredom of this work and the growing tension between father and son contributed to the appeal of far-off Australia.

His Swedish father, Axel sr., had married a Yorkshire girl, and had served with distinction as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the British Army during World War I. In 1919, however, the family decided to return to Sweden, and sent Axel jr. and his sister ahead to stay with relatives on the island of Gotland. Consequently Poignant received a haphazard education partly in England and partly in Sweden.

His schooling was further disrupted by a serious back injury caused by a fall from a horse, and his lack of formal qualifications precluded further study. He had shown an active interest in photography from an early age, therefore it is surprising that he did not think of taking it up professionally. Poignant had experimented unsuccessfully with a pin-hole camera as early as 1919, but the ingenuity of his first successful picture (cat 1), a double exposure, indicates more than the usual teenage interest in photography.

The enthusiasm with which he assembled an album of prints on his voyage out and during his training at Scheyville also shows an early potential for making a story in pictures.

Axel Poignant arrived in Australia in July 1926 and, after brief training as a farmhand, he set out eagerly for Coolamon, New South Wales, and his first job. He recalls being collected by the gruff'wheat cocky' in a dray, and how incongruous they must have looked together, himself still a pale, thin, blond youth with a British accent and a tin trunk containing a dinner suit.

|

|

These first years in Australia, however, were years of hardship. Enteric fever, appendicitis and jaundice in quick succession made the young migrant unfit for heavy farm labour. Undernourished and lonely, he searched for employment in the city, but without success.

After a period of sleeping rough in the parks he rolled his swag and returned to the bush. When he couldn't find casual work he helped himself to corn and slept in abandoned sheds.

Back in Sydney in 1928 and still without work, Poignant was helped by a friend who knew the district to chose a camp-site in French's Forest, overlooking Dee Why beach. He pitched a tent there, and for the next few months made a little cash (6 shillings a week) by picking wildflowers illegally.

Every Friday he made the journey by tram and ferry to the city to sell them to the wholesale florists in Rowe Street, and then he went to the Municipal Library to borrow his week's supply of books.

In spite of his meagre diet of bread, powdered milk, dates and water, Poignant recalls this period as a happy one when he learnt about Australia through the works of writers like Prichard, Upheld and Idriess, and read widely from Bernard Shaw to works of natural history and science. 1 |

About this time Poignant attended Theo-sophical Society lectures at Adyar House, and on one occasion fainted from hunger. From 1929 on theosophical friends provided Poignant with spiritual comfort and practical help, and for a while he lived at the society's community house, 'The Manor', at Mosman.

He retrieved his stored trunks and with the aid of a good suit obtained employment first at the Electrolux Co., and then at Gestetner Office Machines. Here his work involved the half-tone stencil process and his interest in photography revived.

Home Portraits

A chance request to take a home portrait immediately suggested to Poignant a means of supplementing his poor salary. Without money even to buy film, Poignant pretended to take the portrait with a borrowed camera, and was paid. Then claiming that the film had been spoiled in the processing, he asked for a second sitting. With the advance payment he was able to return with film in the camera. Other orders followed and a fellow resident at'The Manor' recalls Poignant's long hours in a laundry darkroom.

During this time at'The Manor'Poignant met and married Sandra Chase, and in 1930 the couple returned to live in her mother's house in Perth, Western Australia. Mrs. Muriel Chase was a journalist on the West Australian newspaper and for the next few years, in a sympathetic atmosphere, Poignant was able to work from home as a photographer. He specialised in portraits, particularly of children, and as a feature he provided his clients with the proofs assembled as a small booklet for which he charged five shillings.

|

|

Aerial Survey and the Sharp Print

Not content with the wedding and society portraits that were beginning to fill his order book, Poignant sought to extend the range of his photography. He experimented for a time with the romantic, pictorial style of art photography with its elaborate techniques for creating idealised images.

Then in 1934 Poignant began working with the Western Mining Corporation's aerial survey department. This experience taught him the value of maximum print clarity and he found the aerial perspective exciting.

When he tried to discuss the impact of this work on himself with A. Knapp, a leading exponent of Pictorialism in Perth, Knapp's disparaging comment about'how painful it must be to have to take sharp pictures' was one of the factors which convinced Poignant that the Pictorialist approach was not one he wished to pursue in his own photography.

Poignant spent the next few years consciously developing his craft and trying to clarify his ideas about photography. He knew that he was less interested in photography as an art form than in searching for subjects that he could interpret with his camera. His concern was for content.

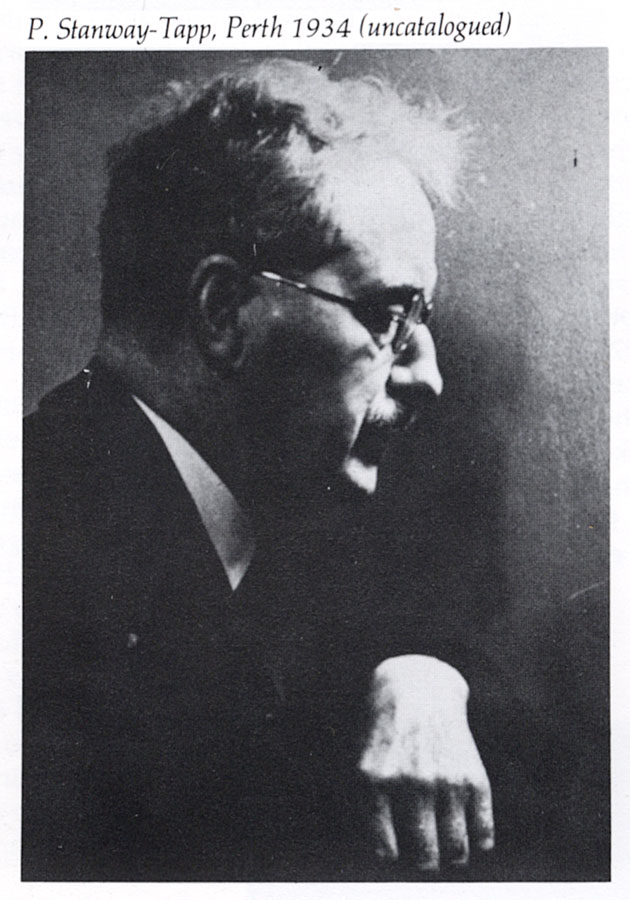

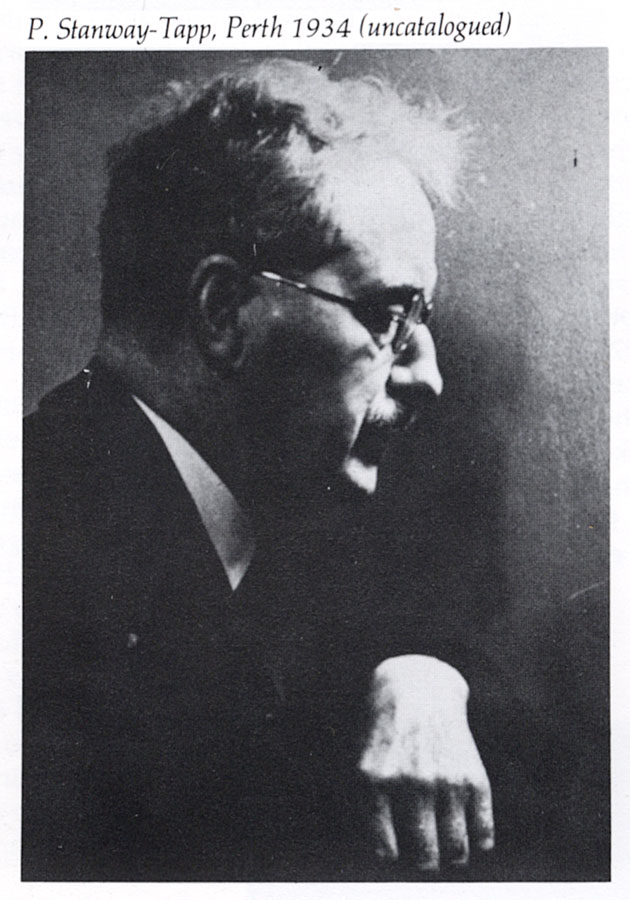

In this he was encouraged by P. Stanway-Tapp, head of the West Australian's photography department. |

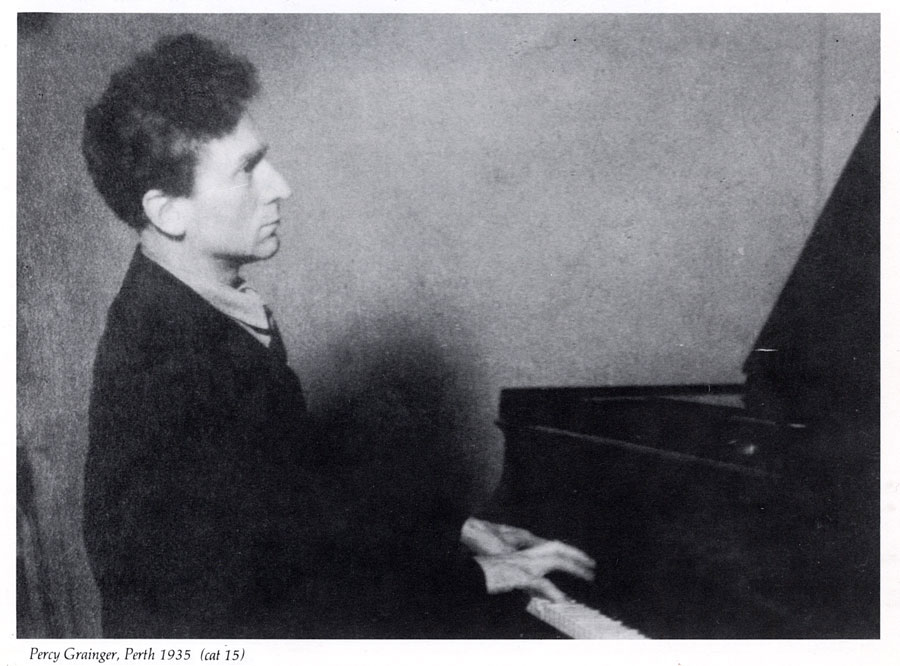

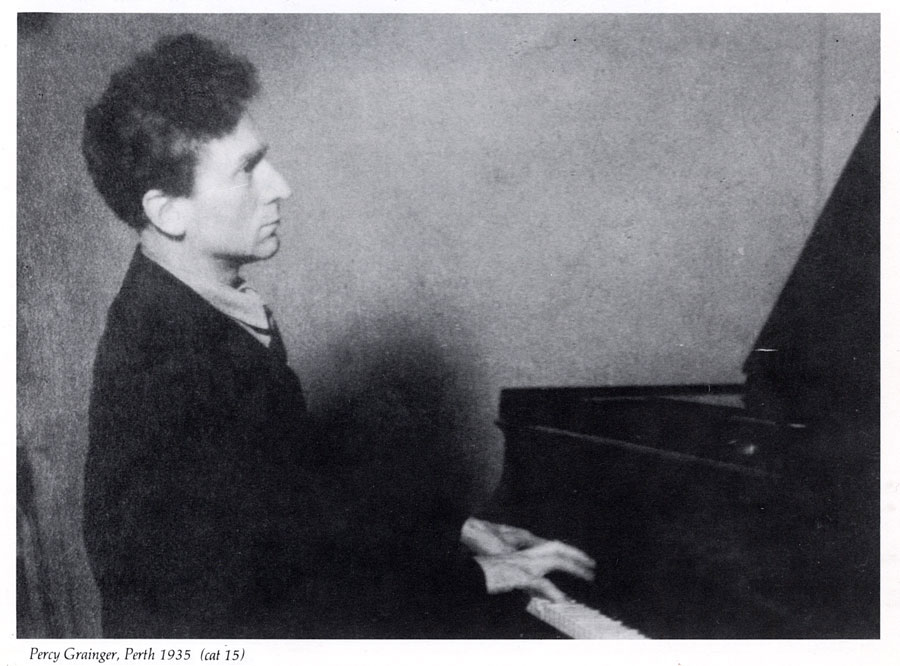

A comparison of a rather studied salon-type portrait of Stanway-Tapp of 1934 (fig 1), which Poignant felt to be his first successful portrait outside commercial work, with the more intense mood of a study of Percy Grainger in 1935 (cat 15), is revealing of the development in style the young photographer's work was under-going. Both works however, share the softer focus preferred by the Pictorialists.

Many years later in 1959, when reviewing this period of evolution in his understanding of photography Poignant wrote: 1 tried all the tricks such as texture screens, bromoil and soft focus to create atmosphere and to try to achieve greater esoteric and artistic expression. Although at various times 1 thought 1 had found what I was seeking, expecially when well-meaning people approved my pictures, after a while dissatisfaction would set in. The next stage began when 1 abandoned all attempts to be 'artistic' by externally imposed convention and formula. Instead 1 tried to put whatever photographic skill 1 had to some useful purpose.2

Poignant was not alone in his desire for a content in his work which was more meaningful than the idealisation of the Pictorialists. As early as 1910 new attitudes to the function of photography as a medium had began to be articulated.

Variously called; 'straight', 'modern', the 'New Photography' and 'documentary photography' these developments were widespread by the thirties. These terms are not necessarily synonymous but in whatever guise their adherents believed in exploring the camera's unique capacity to present aspects of the real world and contemporary life.

All histories of photography deal with these developments which are regarded as landmarks in the medium's achievements. The introduction of 35mm cameras with the production of the German Leica in 1925, is considered to have created, or facilitated, a new formal language unique to photography. Its compact size, ease of operation and faster shutter speeds enabled photographers to make more spontaneous pictures utilising a wider range of viewpoints and to work in situations not possible with earlier cameras, even the miniature pocket type.

The Standard Leica and the Photo-Essay

The time spent at the aerial survey laboratory was decisive for Poignant in another way, because his earnings there enabled him to buy a second-hand standard Leica camera from the English foreman. Equipped with the Leica, Poignant began to extend the range of his work to include press photography, and his first news picture of a store fire was published in 1934. As he gained confidence Poignant began searching for press subjects. He would introduce himself to visiting personalities who arrived by sea at Fremantle, and that is how he came to photograph Percy Grainger, though this lyrical picture was never published.

The 35mm camera was also allied to the appearance of the photo-story layout in illustrated magazines which themselves had been made possible by advances in printing technology in the twenties. The photo-story was a vital part of documentary photography. A related set of pictures were used to dramatise a story for readers, whilst also often contributing an insight into the subject more fully and forcefully than any single image. This concept distinguishes the attitude of documentary photographers from the more neutral use of the camera to take simple record shots.

In 1934 Walkabout magazine was launched in Australia. Other picture magazines existed but Walkabout was particularly interested in the photo-story and provided work for the new breed of photo-journalists. It also catered for and encouraged a national pride and, as its name implies, was concerned with covering outback Australia and the Aborigines. It was published by the Tourist Department and authors such as Arthur Upheld and Ion Idriess, whose work dealt with Australian identity and character, were frequent contributors.

From the late twenties Australian photographers had become increasingly enthusiastic about modern trends overseas despite their lack of access to original work. They depended on a fitful supply of foreign photography magazines such as Das Deutsche Lichtbild, (Poignant's Aunt Maria sent him the issue for 1933), odd reports in local journals or illustrations in the picture magazines. Poignant recalls realising many years later that he had seen early photo-essays by Cartier-Bresson but had not known at the time about Bresson's significance as a pioneer of documentary work. In 1934 Poignant was still grappling with the new ideas.

On the eastern coast, a contemporary, Max Dupain, in Sydney was establishing his first studio and equally passionately exploring the new trends. Dupain however, chose to explore the more formalist side with an interest in the structure of things. At this time Dupain was not as involved with the photo-story as Poignant was to become.3

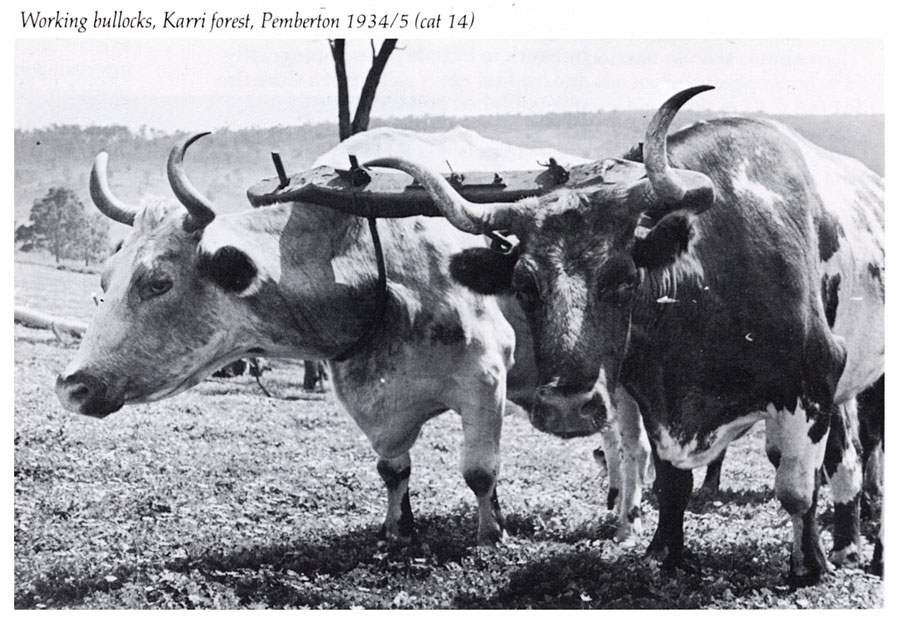

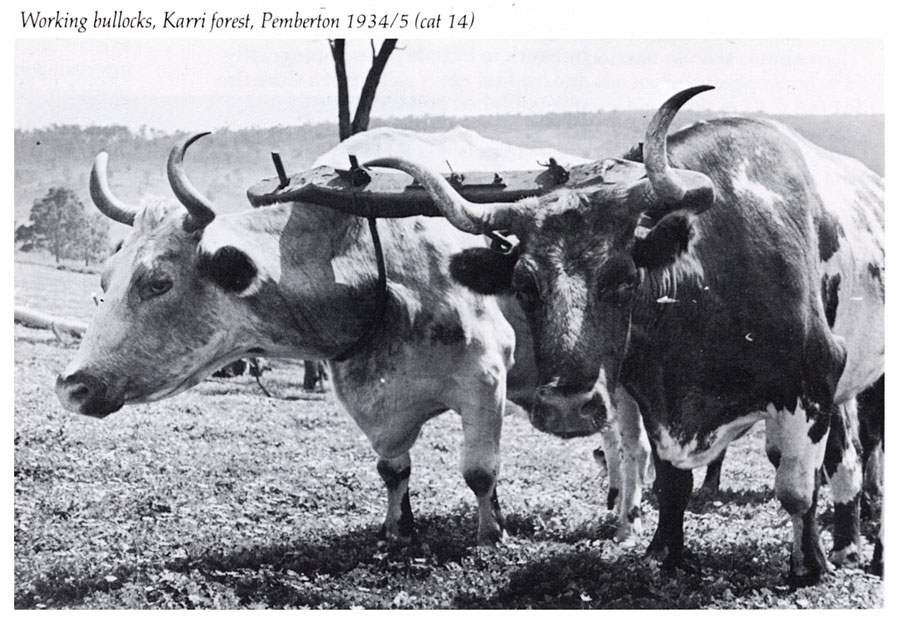

Poignant's first experiment with the photo-story was an essay which he made in 1934/5 on the timber getters of the karri forests at Pemberton. Stanway-Tapp had drawn Poignant's attention to the destruction of the forest. Because he felt somewhat diffident about the exercise, and did not expect to get it published, Poignant printed most of the photographs as postcards.

This tends to conceal the narrative intention of the essay. It is only on seeing the close-up shot of yoked bullocks as an enlargement — when the dramatic effect of the low-angle and bold cropping can be appreciated — that it is clear Poignant was beginning to exploit the Leica and the photo-essay format, (cat 14).

It is also significant that later, in 1941, Poignant selected this picture from the series for inclusion in his first exhibition. It was titled from Katharine Susannah Prichard's story of the pioneer spirit of the timber getters in Western Australia, Working Bullocks, published in 1926.

The title indicates Poignant's sympathy with the independence of the timbermen, despite his awareness of the destruction of the forest.

In 1935, after the break-up of his marriage, Poignant established a studio of his own in Perth's main shopping arcade, London Court. Portraiture still constituted the main source of his income.

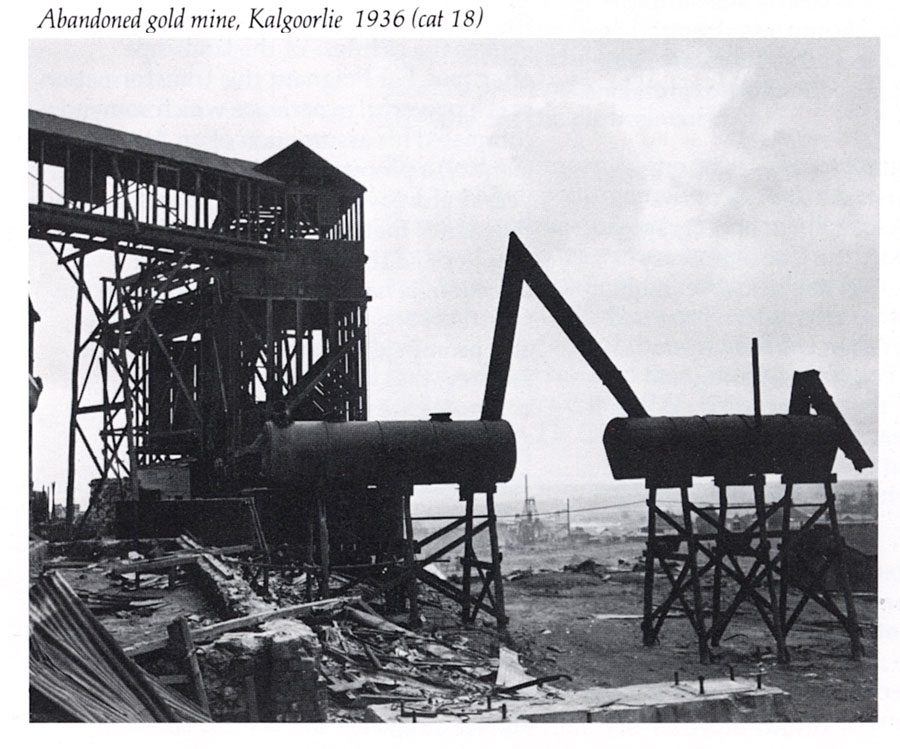

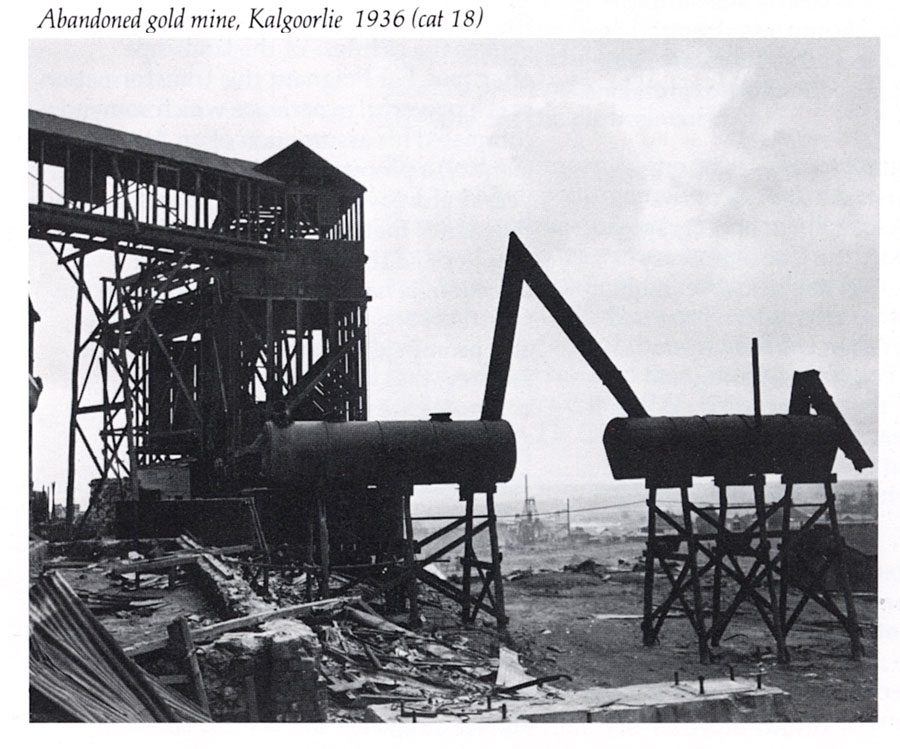

However, he was keen to get out into the country and, whilst photographing school children in Kalgoorlie in 1936, Poignant took time to develop an essay on this mining town. As with the logging essay he was aware of the social problems and destruction that mining brought. The boom years were over and many mines were abandoned to fossickers who eked out an existence, picking over the dumps.

The intention of this essay is clearer than the tentative view of the loggers. The character is one of rewards — shown in the bold stance of the gold pourer (cat 16) and losses, as in the pictures of the poor quality housing for the miners or the abandoned mine works (cat 18, 20). The essay was not published but a number of photographs from it were subsequently included in Poignant's first exhibition in 1941.

Distinctive Vision Emerges

In 1938, on a trip to Pingelly, Poignant's distinctive vision as a photographer emerges. People, especially the independent characters of the bush henceforth command his attention. Where the character of the subject in earlier portraits is distant, in the Pingelly portraits such as the one of Con Henry (cat 22) the subject is confronted directly and dramatically. Poignant has become more aware of his task.

Later, in describing a picture of a camel driver from this period he wrote:

1 decided that whether he was looking after the camels or donkeys was unimportant — it is his personality, expressing outback Australia so the camels were excluded. The only rule is to keep it simple as possible, so a low angle was chosen. This kept the background plain and strengthened the effect of a strong shadow under his hat, caused by the harsh sun of the interior. Only things which contributed to the overall impression were included in the picture, and these in their proper order of importance.4

It was also at Pingelly that Poignant's interest in Aboriginal people was first aroused.

During these years he formed friendships with Norman Hall, editor of the Pingelly Echo, Harold and Dorothy Krantz, Alex and Katharine King, and Pat and John Thompson all of whom had strong social and political awareness and wide cultural interests. Alex King, in particular, was interested in the documentary film movement. Poignant's work of this period shows an awareness of the work of American Farm Security Administration photographers.

In 1939, the year after his Pingelly visit, Poignant met Vincent Serventy, a young school teacher who was a passionate naturalist. The occasion was a wildlife show at the Perth Town Hall organised by the Naturalist Club of which Serventy was secretary. Poignant joined the club and went on many field trips.

Their shared interest in wildlife led to a close friendship between Poignant and Serventy and the latter recalls how club members were impressed by Poignant's dedication to realism in his nature studies, with his use of the close-up and attention to sharp detail. His powerful image of a young osprey on the Abrolhos Islands (cat 25), was considered a landmark in nature photography.

Poignant's comments (see above) about his picture of the camel driver, could apply equally to this portrait of the essential character of the wild bird. Poignant had also begun working with 35mm colour transparencies and 16mm movie film, and combined with others in the club to record the local colonies of Fairy Penguins on film.

|

|

Poignant-Missingham Exhibition 1941

One of the most rewarding friendships of these years, effecting the development of Poignant's photography, was with Hal Missingham, who had returned from art studies in London in 1940.

Missingham's exuberant but direct observations were as well-known to his friends then as they are now. Like Poignant, Missingham was a Leica enthusiast and he had done considerable work in photography both as an aid to his graphic design and as a medium in its own right. Missingham admired Poignant's technical skill and compositional strength as well as his direct approach to the subject.

He encouraged Poignant to make larger prints and, in 1941, they held a joint exhibition in Perth at the art gallery of Newspaper House; the premises of the West Australian newspaper.

|

The Poignant-Missingham exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue which was unusually large for wartime and an era when one-person or small group shows were in general, exceptional.The foreword by Alex King articulates the position of those interested in the new developments in photography in the thirties. In his staccato sentences, King explains the philosophy of the 'New Photography' and some of the social concerns and beliefs of the documentary film movement, and expresses his passionate belief in the role of photography in modern society:

We docilely submit to our machine civilisation and are hurried round the world in a blur. The camera focuses, with an almost incredibly sharp observation, on the complex moving detail of life and holds it still for us ... so that we get back the innocent eye of childhood.

The contradiction between King's depiction of the photographer as someone alert to the 'beautiful or sordid or grotesque behaviour of things and people that is the root of all art; and the camera as an inhuman instrument with cool aloof vision that 'stares like a shameless child' is typical of the aesthetics of the New Photography.5

Whilst King accurately states the view of the New Photography, Poignant's work was concerned with more significant issues than the simple relevation of the formal character of the world. By this time Poignant was fully conscious of his concern to use photography as a means to an end which was to express clearly and simply, what he had to say abouttme subject; 'whether it was a teakettle, landscape, bird or perhaps what lay behind the expressions in a human face'.6

The exhibition itself appears to be one of the first in Australia to present the documentary philosophy in photography.

In Sydney, in 1938, the Contemporary Camera Groupe (sic) had held an exhibition of'modern' photography which favoured formalism rather than the humanism apparent in the Poignant-Missingham show. However the advent of World War II the following year had brought a more sober mood than the celebration of the 'machine age' which the Sydney 'Groupe' had advocated.

The Perth exhibition was accompanied by a lecture programme which took the form of discussions between the two photographers on the uses of the camera. From the reviews it seems that a number of sales resulted and some of the proceeds were donated to the Kindergarten Union. Most reviewers concentrated on extolling the ever-onward path of the technical advances in photography.

The Daily News critic, however, noted that: When you see a picture of a Sturt desert pea or Kangaroo paw or blackboy which exploits the subject's mystery instead of its obvious oddness, or beauty of form in garbage heaps, or another which cries of social abuse, you realise that photography is a process of art not mechanical reproduction.7

Assumption of an Australian Identity

Early in 1942 Poignant joined an expedition by camel to check the wells along the Canning stock route which ran from Wiluna railhead past Lake Disappointment and as far north as Hall's Creek. This was a precautionary measure to facilitate evacuation of cattle from the north in the event of an invasion by the Japanese, who had already bombed Darwin.

Recent rains had brought an end to a seven year drought and, during the three weeks he was with the expedition, Poignant witnessed a phenomenal regeneration of the desert: This was the first time I experienced this miraculous transformation; the endless plains of wild flowers, the budgerigars in their thousands near the water holes, and the vast skies.8

The inclusion in this exhibition of a colour shot of the desert in bloom (cat 27) well evokes the richness of the landscape after rain. For Poignant this transformation was a powerful experience which somehow completed his assumption of an Australian identity, a process which had begun sixteen years before with his arrival in the country. Poignant's matured ability as a photographer and the confidence and the direction he had found in Perth within the naturalist and documentary movements also prompted his conviction, during the journey, that he had something to communicate in images about Australia.

His journey along the Canning stock route was decisive too in providing Poignant with contact with Aborigines on the cattle stations. In acquiring a new sense of identity himself, Poignant also seems to have recognised a brotherhood with the land's first inhabitants. The portrait of an Aboriginal girl breast-feeding a new-born baby (cat 29) and that of the head of a stockman against the sky (cat 28) show a new mastery in Poignant's use of the close-up and low angle first seen in Working Bullocks (cat 14).

The two portraits reveal a relaxed assurance on the part of the individuals photographed, but they also show — in the monumentality of composition and form — a recognition on the part of the photographer of the rich and powerful culture represented.

In the hundred years of photography which preceded these works few similarly humane portraits of Aborigines exist. This draws attention again to the distinction that must be made between the simple factual photographic record, and the humanism and brotherhood that the documentary movement aspired to.

The Canning stock route photographs belong in the same context as the work of Edward Weston, particularly his Mexican portraits of the 1920s, the photographs of the Farm Security Administration, and the earlier direct realism of New Photography portraiture.

However, the influence of Theosophy which stressed the unity of all life — man, animal and even inanimate earth — may also account for Poignant's pioneering sensitivity towards the Aborigines as more than anthropological specimens. As with his contemporary Max Dupain, Poignant found in the close attention of the New Photography to the phenomenal richness of the everyday world a philosophy to fit his childhood passions for the natural world.

Poignant accompanied the expedition as far as Lake Disappointment. On his return to Perth he enlisted for war service and his portrait studio was taken over by his assistant. He was sent to Sydney where he spent the next two years processing radar film. With the end of the war in sight Poignant was released from the army to join the camera crew of the British Ealing Studios' film The Overlanders.

Committed Documentary Approach

Selected on the basis of the natural history footage he had filmed before the war, Poignant grasped the opportunity to work professionally in film with the director, Harry Watt, an articulate and experienced exponent of the documentary film movement, even though The Overlanders was a feature film.

The outcome of this experience was Poignant's 'conscious commitment to the documentary approach in both still and movie photography.' The nine months he spent in the Northern Territory on The Overlanders also stimulated his interest in the Aborigines and he began reading books such as Spencer and Gillen's Across Australia (1912) and TheArunta (1927).

Poignant's next assignment was as a cameraman for the Film Division of the Department of Information, on the film, Namatjira The Painter.

The three months he and the others (director, Lee Robinson and producer, C P Mountford) spent with Albert Namatjira and his family were the longest time he had had with Aborigines. For much of the time they travelled together on camels. The Aborigine in charge of the animals had accompanied Spencer and Gillen through Central Australia and, under his tutelage, Poignant began to understand at first hand the bond between the Aborigines and their land.

Over the next decade Poignant returned many times to the Territory and travelled widely throughout Australia both as a freelance photographer, and on assignments for the Department of Information, and various American companies such as Encyclopaedia Britannica. Relatively little of his photographic output was published in magazines before the late forties.

For instance, he worked on several stories for AM {Australian Monthly) around 1948 but, curiously never had photographs published by Walkabout, a major outlet for picture stories about the outback in those years. In 1948 he worked again for Harry Watt as a still cameraman on the Ealing studio production, Eureka Stockade. In the same year, Poignant's animal photography became more widely known through the publication of his first book, Bush Animals of Australia.

The preface to a later book, The Improbable Kangaroo (1965) expresses an attitude of respect for his subject that is fundamental to all his work: Photography is only a means to an end, not an end itself. In my case it helped my own interest in Australian animals to grow to a stage where I discovered for myself every animals' right to its own life. When photographing animals one is often privileged to witness moments in their private lives that reveal their skilful adaptation to situations and circumstances. This made me realise that humans have no proprietary right to the world and have no mandate to destroy or change the environment without the greatest care and consideration.

Arnhem Land

It was not until 1951 when working as an assistant to American photographer Fritz Goro, then on assignment in Australia for Life magazine, that Poignant conceived a project which would unite the various strands of his work.9

Since 1942 on the Canning stock route expedition he had had a conviction that he wished to communicate something about the land, and that the Aborigines somehow held the key. He had experienced the Aborigines mostly as a 'shadow community' on the cattle stations. On hearing of plans to establish a government station on the Liverpool River in Arnhem Land, Poignant realised that this would perhaps reduce yet another group to such a shadow community. He resolved to go there and record their traditional life before it was too late.

Poignant had already read Black Civilisation (1937), a classic ethnography of the people at Milingimbi, Arnhem Land, by the American anthropologist, Loyd Warner. Although he tried to inform himself, Poignant did not set out to make an anthropological study; he understood his role to be that of a photographic witness, and he hoped that by recording the detail of daily life he would be able to convey something of the whole, so that the quality of the life which was being lost would not go unreported.

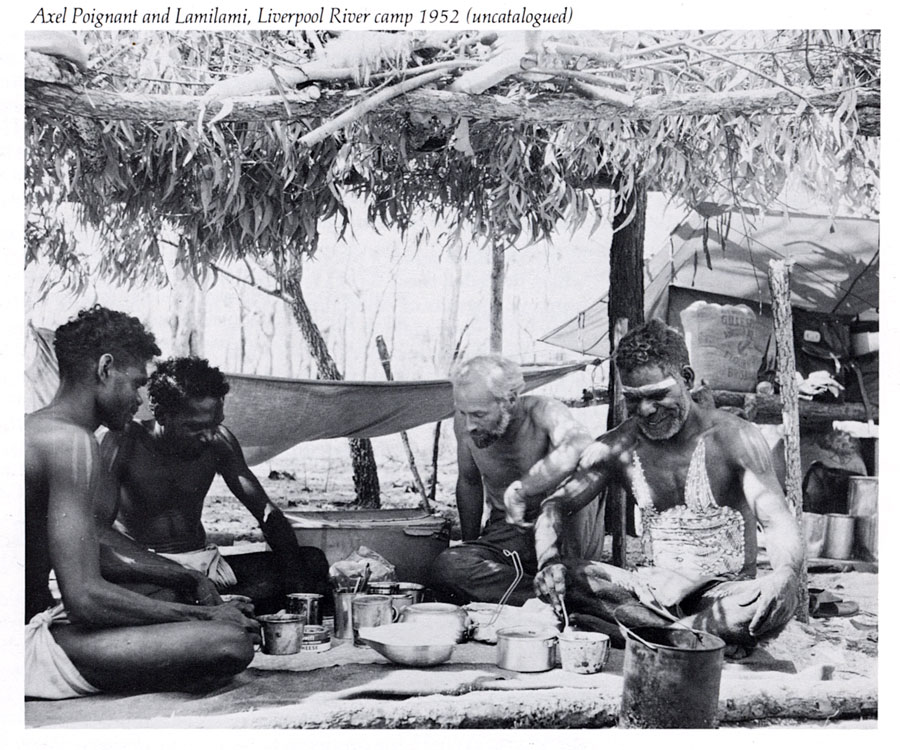

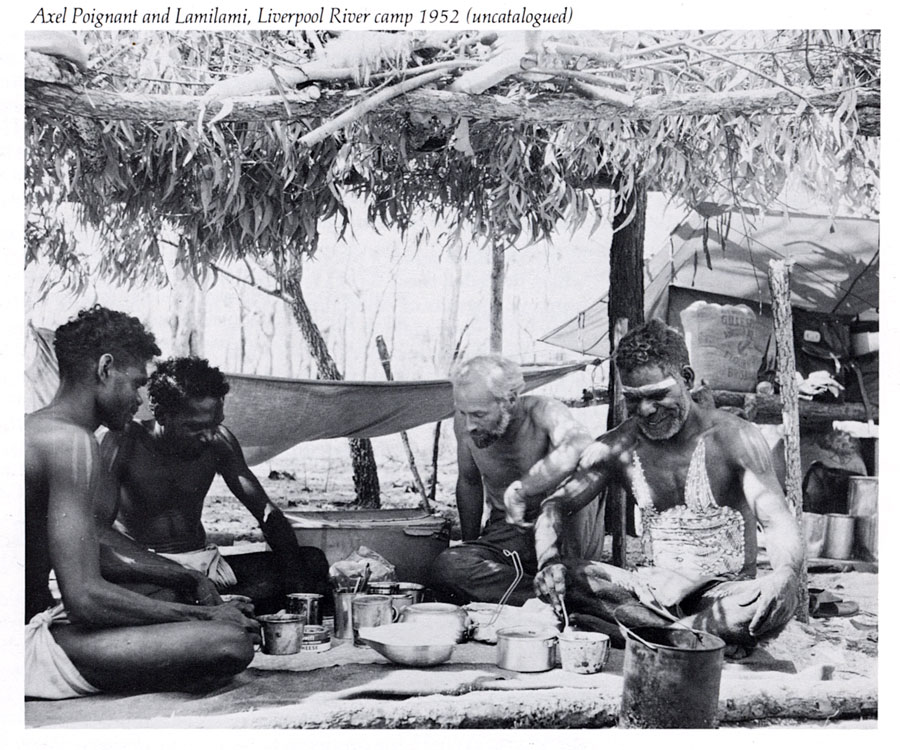

Permission to enter the reserve was obtained from Paul Hasluck, then Minister for the Interior. Supplies were provided and the help of three Aborigines from Goulburn Island mission was arranged. One of these Lamilami, was both a Christian and a respected tribal elder. He was Poignant's chief interpreter, and his autobiography, published in 1974 gives an account of the Aborigines' view of the photographer.10

The four men set up camp on the west bank of the Liverpool River and Poignant recalls how'once the lugger had gone I quickly sensed a change in our relationship — I was a guest in their country.' The spot where they camped was a traditional meeting place, rich in seafood and game, as well as having a source of fresh water.

Within several weeks some sixty Aborigines had set up camp around them, including some who had walked a long way in search of relief from a severe drought in their own hunting grounds. One of these, Narrana, was an extraordinary man in both physique and character, and Poignant's photographs of him suggest an unusual degree of rapport between them. They have a quality which is both direct and mysterious.

Poignant spent three of his five months in Arnhem Land in the camp at Liverpool River and made thousands of photographs of many aspects of daily and ceremonial life. About 2000 documented file prints selected from all his Arnhem Land negatives have been placed in the National Library of Australia, Canberra.11

Access to the Liverpool River had been by Methodist mission boat which in due course collected Poignant, and took him to Milingimbi. Full of the experience he had just had, and attracted by the children he saw around him, he decided to use the three weeks before the boat left for Darwin, to photograph a story for children.

Raiwalla, a leader in the community, provided the story line, Beulah Lowe, the teacher, translated it, and the people readily participated.

First published in 1957 as Piccanniny Walkabout; the book was redesigned and re-titled Bush Walkabout by Poignant in 1972. It has altogether sold over a hundred thousand copies. The UNESCO commendation awarded to it in 1958 as 'a children's book promoting understanding between peoples', draws attention to the context of its publication in the years of the Family of Man exhibition, a period of optimistic humanism when it was hoped to help resolve global conflicts by the recognition of universal brotherhood.

Poignant's conception of a picture story in photographs for children was a pioneer work in this field. Its layout was a product of his film experience and long term interest in arranging sequences of pictures.12

Poignant was not able to publish a book of his own selection of the Arnhem Land photographs. To do so would have required the kind of resources and time few working photographers can mobilise unassisted — and more significantly the public interest in the subject was lacking.

Many images were used in books such as F D McCarthy's Australia's Aborigines (1957), but the humanist and documentary character of the work is diminished within such anthropological publications.

In Poignant's long career his Arnhem Land work represents a strongly motivated, complex and sustained effort which deserves consideration on many levels. One is the role it plays in his personal development. For instance, a new element emerges, namely that of the depiction of tribal life as a balance between self-reliance and communal interdependence.

There are numerous images of the nurturing of the young by elders. Teaching the Lore (cat 66) well expresses this bond, a relationship which contrasts strongly with Poignant's own lonely youth.

Another aspect of the work is the photographic portrait of the Aborigines it presents. Here the value lies not only in the anthropological information provided but also in the simultaneous evocation of a depth of culture which is rich but never familiar. Many of the Arnhem Land photographs radiate an empathy that is compelling and positive in its effect.

One image, perhaps, stands as a visual metaphor of the encounter between the representatives of the two cultures. It is the portrait of Narrana and his two sons (cat 58) standing in the only shade while the photographer changes his film.

Six Photographers Exhibition

Poignant's work had some exposure through the Six Photographers exhibition held in Sydney in 1955. Poignant joined with Max Dupain, Kerry Dundas, David Potts, Gordon Andrews and old friend Hal Missingham, in regular sessions where they discussed each other's work and gave mutual support for their shared documentary philosophy. The late forties had seen a considerable growth in illustrative photography, especially for advertising and promotion.

Fashion photography in particular attracted notice because of its glamour. Few opportunities existed for photographers such as the six in the group to show their work, which belonged in neither the slick trade shows nor the camera club salons devoted to a picturesque aesthetic at odds with the groups interest in realism and spontaneity.

The catalogue for the Six Photographers exhibition reaffirmed a view of photography evident in the 1941 Poignant-Missingham exhibition:

We consider that what really matters in a photograph is the image itself, the subject matter .., The six photographers exhibiting all have a real belief in humanity and in the camera as an important means of recording contemporary life.

Poignant's exhibits were largely drawn from his recent Arnhem Land work and naturalist studies. Two key images from earlier years, the Aboriginal girl and new-born baby (1942), and the Fledgling osprey on the nest (1939) were included.

Outside of the group Poignant's work was not very well known though the picture of the Aboriginal girl had been awarded a gold medal by the selection committee for the Australian Photography 1947 publication eight years earlier.

Unfortunately the latter publication (which had hoped to become an annual exposure of quality photography), was an isolated event and Contemporary Photography, a magazine founded in 1946, which gave support to documentary photography, had folded by 1950.

Thus no serious critical appraisal of the Six Photographers show was published. The odd newspaper review praised the vitality of the camera-artists in terms similar to the reviews of the 1941 Poignant-Missingham show. The group disbanded after the exhibition. The energy and sense of purpose existing among the six members seems absent from subsequent photography exhibitions over the next decade.

London in the Sixties and Seventies.

In 1956 Poignant left Australia to return to Europe for a family reunion. His second wife had died tragically, and in 1953 he married Roslyn Izatt, a graduate in anthropology and history, then working for the Film Division of the Department of Information. The Poignants established a base in London where they have remained for family reasons.

During the sixties, already battling against isolating deafness, and at an age when most photographers are consolidating a career, Poignant estabished himself as a freelance photo-journalist, working for newspapers and magazines such as The Observer, The Geographical, and the Times, of which his old friend Norman Hall was picture editor.

Many projects of these years were done in association with his wife, Roslyn. In 1969 they spent a year in the Pacific Islands. One outcome was the production of two books for children in the style of Bush Walkabout; Kaleku the story of a boy growing up in a changing New Guinea, and Children of Oropiro, set on the Polynesian island of Raiatea, near Tahiti.

Poignant's London work of the sixties and seventies continued to exhibit a freshness of vision, and his frequent choice of subjects such as the deaf and the homeless suggests that his sympathies lay with the concerned photography of the period. However, it is his portraits of artists, musicians and dancers — which again form an important part of his output — that his deeper insight into the individuality of his subjects (of character) found expression.

There are intimations of the transcendent power of creativity, a quality first evident in the quiet self-containment of the 1935 portrait of Percy Grainger. In his later portraits hand gestures often seem to echo the symbolic gestures of ballet or eastern dance he had observed in the Indian dancer, Rukmini Arundale, in Sydney in the late twenties (cat 5).

Images for an Australian Identity

The documentary movement provided Poignant, as it did Dupain, with a codified philosophy which in each case fitted the basic temperament of the photographer. The specifically social or political aspect of the documentary movement is not its whole spectrum. Indeed the documentary movement often appears to have taken over the interest of the earlier New Photography in a transcendental approach in which actuality is scrutinised in search of the essential and universal.

This paradox is noted by Poignant in 1978 when summing up an account of his career:

... the challenge remains of making visible the elusive inner reality that lies behind the documentary image so clear and full of information.13

Thus Sir Michael Tippett's insight into the nature of creativity as expressed in the quotation Only through Images awakened a deep response in Poignant. As a self-taught photographer and reluctant writer, Poignant says that he feels compelled to express himself through 'images which must in the end speak for themselves.' 14

The understanding of photography as a visual medium is restricted by the lack of awareness that its images can be highly realistic yet simultaneously present a point of view of the author.

Poignant's Australian imagery has several recurrent themes; a preference for portraits in which the subject appears self-contained or 'centered' in the terms of eastern philosophy. In the Australian pictures whether of Europeans, Aboriginals or wildlife, his subjects are comfortable within their environment.

One of the most compelling images in this vein is that of the lone swagman determinedly making his way through a deserted landscape. Such bushmen are archetypal figures in the cultural history of Australia since Europeans settlement. Much of the mythology of national identity has focussed on the Outback and those who have attempted to come to terms with the rigours of the land. It is not surprising that the picture of the swagman was chosen for the cover of W F Mandle's book on Australian identity, Going it Alone (1978).

Through his own journeys across Australia, and his original voyage from his homeland, Poignant is himself something of a 'swagman'. The identification with Australia which he found through his experiences of in the Outback led to a body of work which belongs in the literary and visual tradition running from the bush stories of Henry Lawson to the mythic visions of painters such as Sidney Nolan.

Reference

- The hard existence of the unemployed in this era of poor social welfare contrasts sharply with the ecstatic celebration of the future 'machine age' found in contemporary writings such as Jean Curlewis' 'Sydney' Australia Beautiful: The Home Easier Pictorial Sydney No 1928.

- 'Filming in Australia', Filmstrip News No 3,1959. For an account of pictorial photography and new developments in photography in Australia in the thirties, which favoured realism over the romanticism of the former, see G. Newton Silvers Grey, Sydney, 1980.

- Standard histories of photography deal with the development of 35 mm cameras and the documentary movement eg. chapter 11, B. Newhall The History of Photography, 1964, New York, Museum of Modern Art, more recently see Ian Jeffrey Photography: a concise history, 1981, London, Thames & Hudson. For an account of Dupain see G. Newton, Max Dupain, Photographs 1930-80, Sydney, 1980, David Ell Press

- 'Camera Class', AM, May 1952 p61.

- An account of the developments is in David Mellors (ed) Germany: The New Photography. 1927-33, 1978, London Arts Council of Great Britain. Their influence in Australia is dealt with in Max Dupain Photographs 1930-80.

Alex King was a lecturer in English at the University of Western Australia 1932-41. His article in The West Australian Sept. 18,1940 p 18 'Art & Democracy' in which he states how'Art which in its popular form could show the way to a decent life and stimulate democracy ... breathes the life of today and the spirit of the people', reveals more clearly his interest in the ideas of the documentary film movement.

- 'Filming in Australia' op cit

- 'Camera instead of paintbrush', Perth Daily News, 1941, September 18, p 12. Other reviews Art Gallery of New South Wales photography archive.

- Australian Photography: A contemporary view, 1978,' Sydney, p 10.

- Though Goro was on assignment in Australia for 12 months, only two stories appeared in Life; one on the Barrier Reef February & March 1954 and one on Arnhem Land. Some of Goro's Arnhem Land photographs were published in the American Society of Magazine Photographers PiVriirf/bimtn/1957. New York, Ridge Press. Goro acknowledged Poignant's contribution in a letter to the latter 4/2/54 'without your kindness, knowledge of location and people, and love of nature, I feel I would never have succeeded'.

- Rev. Lazarus Lamilami, Lamilami speaks, 197A, Sydney Ure Smith, p 194, 224

- A note on the restrictions on this collection is included in the captions section.

- Sucksdorf's Chandra: the hoy and the tiger, English edition 1960; Ylla's the Little Elephant, 1956; Anna Riwkin-Brick Elle Kan 1956, were other childrens books of this period in a similar format.

- Australian Photography: a contemporary view, op cit p 8

- ibid p 8

Use the menu below to open other sections

Exhibition Introductions / biographical details / exhibition prints & checklist

for more on Axel Poignant

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|