THE MIRRORED WORLD OF LEWIS MORLEY

Gael Newton

Originally published in the 2011 publication: Lewis Morley – I to Eye:

In the decades before World War II, colonial Hong Kong was a melee of noise, colour, congestion and traders due to its position and affluence as an entrepôt of the British Empire. Around the city, red and gold Chinese hangings, decorated with mirror panels to ward off spirits, reflected different images of the city depending on to which social world you belonged.

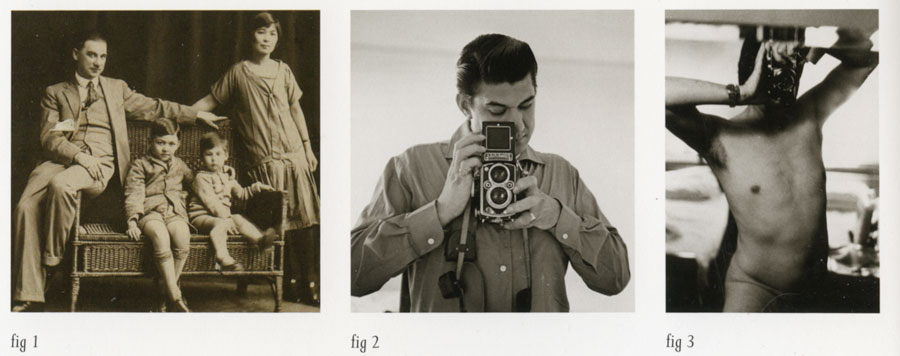

Negotiating the cross-cultural spaces and protocols of Hong Kong was part of the upbringing of colonial gentry - the more so for children of mixed marriages. One of these was Lewis Morley Jr, affectionately known to his family as Freddie, who with Hong-Kong born brother Peter and sister Lucy were the children of British pharmacist, Lewis Morley and his Chinese wife Lucie Chan whose merchant family originated in Canton (fig 1).

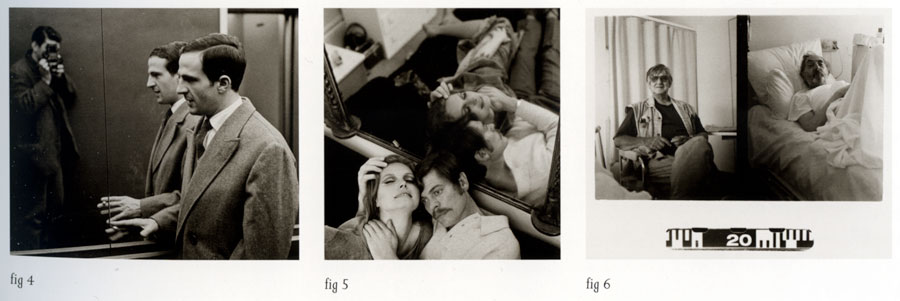

In the late 1930s the teenage Freddie Morley led a comfortable life. Fluent in English and Cantonese, he moved easily between British and Chinese culture and learned the serious business of becoming an Englishman. On the eve of World War II Morley memorialised his schoolboy-self looking remarkably mature and suave, in a view from a low-angled mirror. It is as if he wants to share the spotlight with his respected camera and his environment.

Art historians tend to eagerly scrutinise portraits of the artist-as-a-young-man for clues to their future oeuvre, in this case perhaps we see an early indication of Morley's fondness for viewing things and life from the offside.

This deflected/reflected self-portrait with camera was a motif Freddie as 'Lewis Morley' would return to from time to time in his future life as an artist (figs 2, 3,4, 5, 6)

Now in his 87th year Lewis Morley remains the same gentle, self-contained but affable man with a superb quiff of oriental hair and a distinctive bohemian uniform of polo neck and black leather blazer.

That first Eurasian life of Freddie Morley came to an end in 1941 with the Japanese military wartime occupation of Hong Kong. With his family, Morley was interned at the Port Stanley Civilian Internment Camp for four years.

It was not all bad; Lewis Jr was a tall, sturdy and handsome lad with a sensitivity to getting on with those around him. In camp he experienced sex and cigarettes and other rites of passage but also began drawing his observations of the life and foibles of human nature around him. At the war's closing the Morley family were repatriated to London and only Lewis Snr returned to Asia to sort out loose-ends.

As a young adult Lewis Morley was required to spend 1946-1948 in National Service but emerged from the RAF with an unexpected risky ambition to become a painter. He would have liked to attend a grand tradition Art School but took the opportunity available to him of a place in the commercial art course at Twickenham College in 1947.

Lewis Morley's path to photography as an art and profession came when he took his hobby up again as an aid to drawing figures in action for his painting. His first accomplished street portraits were taken on a trip to Italy in 1949 and show a well formed photographer's eye at work.

These first images that Morley admits into his canon, have an intimate sense of the person and the 'presence' of the objects in their environment. They align with the type of daily life photojournalism being developed in these years in Europe for the big picture magazines, suggesting Morley had absorbed current trends even if self-taught as a photographer.

Morley's most substantial aspiration in painting and photography however, came from his enthusiasm for Surrealist art. This movement's embrace of a wild democracy in which unexpected meaning and visual delight is liberated by the chance collisions and juxtapositions of people, objects, signs, advertising and environmental detritus, or the deliberate staging of dream imagery, had a profound impact on photography from the 1920s on.

Morley felt comfortable inside this Surrealist world view which remains an inspiration. After finishing his course at Twickenham, Morley worked in advertising agencies before spending in time in Paris over the end of 1951 and early 1952 where he took a short course in life drawing at the Academie La Grande Chaumiere.

Morley sold a few paintings before returning to London in early 1952 where in order to paint and photograph during the day, he worked at night as a telephonist hearing poignant and bizarre stories of the citizens unfolding as he worked. Morley's early work after graduation fused a surreal temper and compassionate eye and has a distinctive visual flux slightly looser than that found in existing models of magazine photojournalism.

Whatever the genre-portrait, still life or reportage, Morley has a fondness for creating competing centres of action or detail. Whatever we are looking at with him through his lens, tends to have a 'back story' going on at the peripheries or is glimpsed or seen reflected though another lens-like surface.

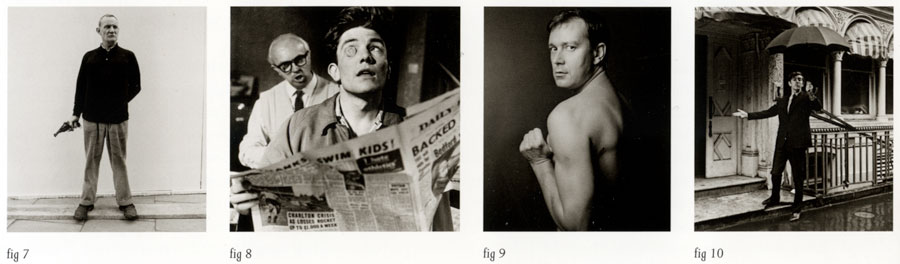

Following through suggestions from associates, Morley turned his interest in the stage to work as a theatre arts photographer. To this first professional specialisation – that now forms the most historically significant part of his archive, Morley brought the spontaneity of reportage rather than the often static 'stills' or glamour portraits of actors, conventionally used for front-of-house or promotional purposes.

His body of theatre work shows constant fresh engagement and invention around the moment of the taking of his images of actors and writers both in their professional roles and offstage (fig 7, 8, 9).

The success of this style of performance-based work and publication of his first images in 1958 in The Tatler billed since the 18th Century as 'an illustrated journal of society and the drama', gave Morley the resolve to set up his own studio as a fulltime freelance photographer. He covered over one hundred West End productions in his first decade.

Morley became involved with the vibrant live satiric comedy theatre scene then gravitating around comedian Peter Cook when he relocated to the same building in Greek street, where Cook had set up his nightclub The Establishment (fig 10). The latter included Cook's compatriots Jonathan Miller, Alan Bennett and Dudley Moore, in the four-man satirical stage show Beyond the Fringe. As a private club Cook and his performers could be as risqué and blasphemous as they liked.

By 1960 Morley's body of portraits and reportage was established enough for him to be given a one person show at the Kodak office in Regent Street. Morley s many studio and street portraits and promotional shots of The Establishment repertory are revered today for capturing a Zeitgeist of the Sixties.

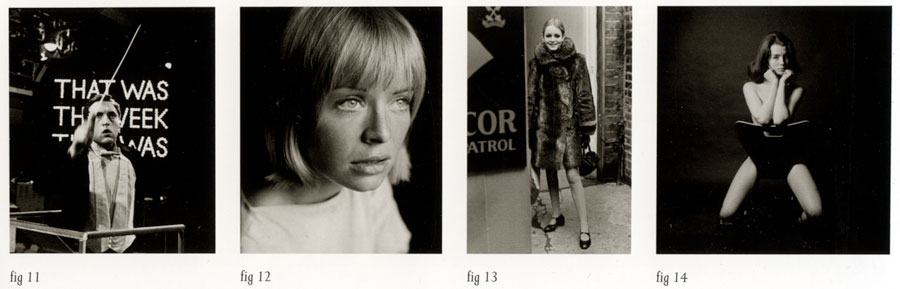

Morley photographed almost all the major players of the era including David Frost whose television show, That Was The Week That Was, brought Cook's brand of satire to a broad public (fig 11), and the Australian satirist Barry Humphries who was to become a close friend. Whether showing Dudley Moore lurching Quasimodo-like across a wet bridge in Regent's Park in 1961 or the four young men as a tarot card-like pyramid of heads, subtle gestures capture their differences as individuals.

After immigrating to Australia in 1971, Morley returned to London in 1994 to make a touchingly respectful portrait of Cook with third wife, Lin Chong not long before the comedian's death from alcohol-related liver disease in 1995.

Opportunities unfolded fast for the new professional photographer placed at the centre of the liveliest theatre arts scene in London and Morley also brought to fashion photography the ambience of street reportage and a touch of the surreal often using non-professional models and actresses.

Regardless of background in Morley's pictures the models somehow remain themselves especially so in the case of his series of images of Susannah York who he photographed both as a model, as an actress and as a luminous muse in close-up in 1963 (fig 12).

For Private Eye magazine, Morley also did anti-fashion spoofs. This was an era when the immediate Post-War generation of anti-establishment 'angry young men' led by playwrights such as John Osborne, Harold Pinter and Joe Orton (fig 9) who had expected post-war Britain to deliver social equality of a new order but saw the old patterns returning.

While far from being a radical activist or Bohemian himself Morley would make some of the now best known images of new street celebrities, playwrights and the actors of the era. The old lines of social stratification protocols and polite language were breaking down and fashion followed suit, by breaking rules of what could be worn where and when.

Fur and denim and sequins became bedfellows. He found Lesley Hornby (aka offbeat Style-Princess 'Twiggy') on the street making the first photograph of her in 1963 (fig 13).

Throughout the decade Morley was employed on portrait, advertising and fashion assignments for The Tatler as well as for other British and overseas magazines and newspapers. Morley also took on coverage of the British pop and rock scene of the Sixties revelling in its playfulness and gender bending extravagance turning a naked group shot of the boy band Sherbert into a sort of modern day twist on famed French painter Edouard Manet's 1863 painting Le dejeuner sur lerbe.

In 1963 Morley was commissioned through an introduction from Peter Cook to promoters of a film, to do studio shots of Christine Keeler the beautiful young working class woman at the centre of a sex and political scandal through her association with Government minister, John Profumo and a High Society doctor.

To meet her contract with them, Keeler was obliged to do a nude shot. Seeing her harassed by the promoters and her discomfort, Morley closed the set and worked with his sitter to make an image both raunchy and respectable and nude but not naked, that was to become one of the iconic nude images of the late 20th century (fig 14).

Saucy women had been draped across chairs in many a French poster and erotic postcard in the late 19th century. French demi-monde artist Henri de Toulouse Lautrec had taken the ambience of the erotica card into the realm of fine art. Morley who liked to visit flea markets and collect overlooked and surreal art and artefacts, perhaps had this ambience in mind when he began to make some thirty shots of Keeler firstly bare-legged but wearing a jumper, to a pose unexpectedly across a severe high modernist chair first on the ground beside it, and then seated and draped across it in conventional poses.

Morley perceived that the closed hour-glass feminine shape of the back could play the role of the medieval Lady Godiva's hair in protecting Keeler from her 20th century naked shame yet meet the requirements of a nude study. The jumper was abandoned by roll two and with Keeler almost kneeling through the chair and her long thighs prominent, Morley tried various poses.

The image that became 'The Keeler Chair' image shows Keeler looking to camera with her head slightly turned and cupped in her hands. It is perhaps the quietest of all the shots looking almost as if made during a brief rest in the shoot.

The appeal of this now much-copied pose comes from the way Keeler's spread legs and joined arms form an X-shape in mimicry of the chair shape, but essentially because it is also a sensitive and respectful portrait of a young woman, Christine Keeler – in the glare of the wrong kind of publicity.

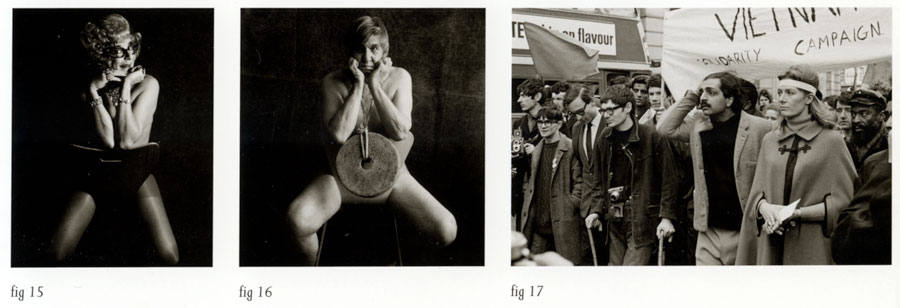

In one deft piece of lateral thinking Morley had rescued his dammed 'Eve' from exposure with a wooden fig-leaf and turned a naked girl into a nude in the classical tradition. The film was not made and the image immediately stolen and circulated against his protests. Morley kept a log of the extensive pirated images and the many take-offs made by others. He eventually reconciled to the loss of control of his Pygmalion image and began making take-off portraits of himself and old friends in 'The Keeler Chair' pose (figs 15,16).

Throughout the Sixties Morley produced hundreds of portraits of artists, performers, celebrities old and young, known and unknown, drawing them into performing for him and his camera. He did not get asked to do the Queen. Morley's beat was the social spaces in between where a range of artisans and creative people mingled freely with each other and the public.

His many close-ups establish the rapport that the photographer had with creative people as sitters though their ability to engage with his intrusion into their lives and accept his subtle direction. His portrait prints are soft enough in the then fashionably high-contrast grainy Sixties way, to be flattering regardless of how dishevelled the subject might be in their role or reality; and allow the viewer the illusion of feeling so close they could feel the star's breath, whilst preserving the subject's persona.

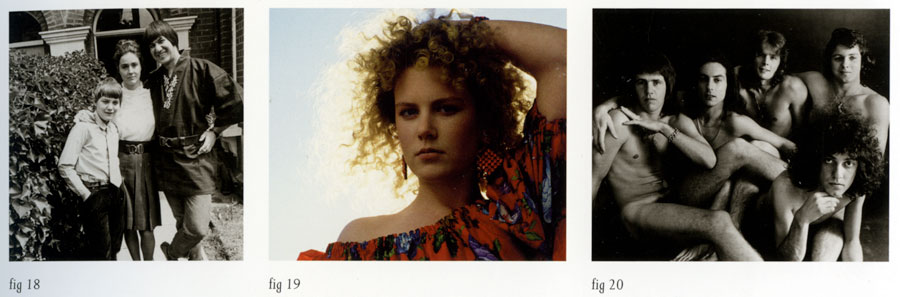

In the closing years of the decade Morley also recorded the rising tide of Beatlemania, but the Beatles were not quite his thing. The activism on the streets of Ban the Bomb marches in the late Sixties however, produced a marvellous set of images including portraits on the Anti-Nuclear protest marches of activists Vanessa Redgrave and Tariq Ali (fig 17).

By the early Seventies television brought the golden era of picture magazines as a single source of work for photojournalists to an end and the energy of the new wave art and culture of the Sixties was flattening. A new generation of Seventies youth shaped by the Vietnam War were by contrast an earnest rather than satirically outrageous lot.

Work became harder to get and less challenging. Encouraged by Babette Hayes, the Morley family moved to Australia in 1971 (fig 18). Hayes became a major contributor to the new Belle magazine and Morley was to be their photographer of choice.

As Morley has said 'Bingo! It was likely the Sixties all over again' and over the next two decades Morley did a wide range of portraiture, fashion, food, interior photography and articles for Australian magazines often involving overseas travel. Most of the magazine work was in colour. His portraits captured Australians as often quizzical and laid-back quirky characters but he also often captured the early years of stars like the young Nicole Kidman (fig 19), before their rise to fame. Morley fitted in and garnered great respect for his support of other photographers and promotion of the art form.

Australian museums largely left him alone and Morley was not the one to push his own work, but as the decades passed, nostalgia for the Sixties revealed the extent and character of his archive. After a meeting in London with Terence Pepper, curator at the National Portrait Gallery, Morley's work was acquired in depth; and in 1989 became the subject of their very popular touring exhibition: Lewis Morley Photographer of the Sixties.

That year Morley closed his city studio in Sydney but continued with commercial assignments as well as projects based on his archive. A retrospective at the State Library of New South Wales in 1993 followed the publication of his autobiography Black And White Lies. Morley ceased commercial photography altogether to concentrate on projects related to his archive in 1997.

While Morley often depicts his career in photography as a case of being 'in the right place at the right time' recognition of his talent as a photographer began as early as 1957 when Norman Hall, editor of the British Journal Photography, ran an article Lewis Morley Painter/ Photographer: Our latest Young Britain discovery.

Morley's later representation of the Sixties theatre arts renaissance, the crazy pop music scene (fig 20) have now become part of a valued historical archive, yet Morley's subjects live on in there vibrant freshness, in the force of their gritty, grainy presence.

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|