A BOOK ABOUT AUSTRALIAN WOMEN:

Carol Jerrems in 1974

Gael Newton, 2005

This essay was originally published in Art & Australia, vol 43 no 2, Summer 2005,

The essay was later editted and reprinted in Up Close, a publication for the 2010 exhibition at Heidi Museum of Modern Art (Melbourne)

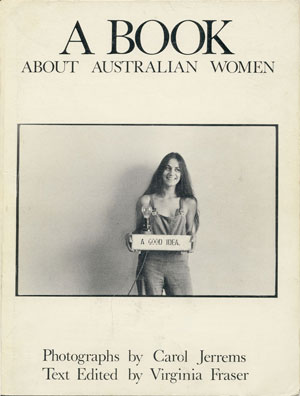

Falling neatly between the 1972 release of Helen Reddy’s anthem I am woman and International Women’s Year in 1975, two young women in Melbourne, the photographer Carol Jerrems and writer Virginia Fraser published A Book about Australian Women. The front cover design was striking and sexy, showing a beautiful young woman in dungarees. She holds a conceptual sculpture by Alex Danko; a phallic light bulb atop a block of wood on which is stencilled ‘A Good Idea’ — the words thus amusingly conscripted to a message about Women’s Liberation.

The headings for the interviews throughout the book cleverly pick up on the same military-stencil effect and evoke the slogans of activism. Typically for the agenda of the times the contents of the book are a proclamation of solidarity and a prediction for a better future for women. |

|

|

The subjects of the 80 or so images in A Book about Australian Women were described by Jerrems in the frontispiece as ‘mostly portraits of artists…painters, sculptors, writers, poets, filmakers, photographers, designers, dancers, musicians, actresses, strippers. Others include women’s liberationists, Aboriginal spokeswomen, activists, revolutionaries, teachers, students, drop-outs, mothers, prostitutes, lesbians and friends.’ A few were visitors, mostly black women from America. All the subjects were of ‘equal importance’, none were identified becoming ‘Types’.

The alphabetical listing at the back was not cross-referenced by page numbers. The texts in the book were from Virginia Fraser’s interviews with unnamed women including artists, from a variety of backgrounds, on their experience of gender politics.1 The project was not intended as an elitist ‘who’s who’ - a note of qualification also underlined by the choice of preposition in the title

ie , A book rather than THE book about Australian women.

The portraits had been taken, some specifically for the book, in the two years since Jerrems had graduated in art photography from Prahran Technical Institute. Two were from 1968 and 1970 in her student years but struggled to be ‘portraits’ under their 60s-style bold graphic design. Images of children opened and closed the book and some subjects were of older role models like Aboriginal writer Kath Walker [later writing as Oodgeroo], actress and script-writer Enid Lorimer, and modernist painter Grace Cossington Smith.

Some already had a profile like Kate Fitzpatrick, Bobby Sykes, Margaret Roadknight and Wendy Saddington, but mostly they were young and emerging talents some destined for continued public prominence like poet Kate Jennings, and cultural critics Anne Summers and Beatrice Faust.

Five images were portraits of Jerrems including a romantic close-up by a man, Stephen McNeilly. Another by Toni Schoefield, a woman friend of the artist, showed Jerrems as a radiant flower-child in hot pants with neon halo rays behind her. Significantly Jerrems, chose two self-portraits for the book one in which she is faceless her identity melded with her camera. Several film-makers but only one other still-camera carrying woman, were included in A Book about Australian Women.

For the book Jerrems, who is described as a full- time teacher of photography, drawing painting and yoga, chose the pictures and determined the layout. The design reveals her skill in precise and assured relationships between single images and sequence. In particular a double page spread of four sequential studies, one blurred, of the beautiful Aboriginal singer Sylvanna Doolan is exquisite. Two images with a distinctive wiggly surface texture from portraits of aboriginal people in Melbourne and Redfern had been exhibited in an Ilford Photography competition in 1973.

The complete Aboriginal studies (excluded from the book as they were of men) made dramatic use of impressionistic texture and blur. While not often among her later published works, are arguably her first major related suite of work. This cinematic feel for flow and panning, foreground to background ‘zoom’ owed a debt to Jerrems art school teacher the film-maker Paul Cox. Jerrems’s own film-making had begun by 1974.

A Book about Australian Women sold well and was positively reviewed but today while pictorially strong, it seems somewhat from a distant planet of past feminist high hopes, energy and enterprise. Scuffed and unloved copies abound in second-hand bookshops. Published by Outback Press, an equally important short-lived independent publishing group, A Book about Australian Women deserves a better fate; it was one of, if not the first, new wave feminist photobooks.

Outback Press was founded by a quartet of young men operating out of a grungy terrace in working class Fitzroy: writer Colin Talbot, entrepreneur and cultural agent-provocateur Morry Schwartz, publisher Alfred Milgrom and Rock singer/songwriter Mark Gillespie. The production values were a bit rough but their project was in sync with a brash new Australian cultural renaissance.

A decade or so earlier they’d have been called beatniks but their alliance with energy of the young, the alternative, working class and street culture came from the Swinging Sixties. The guys were seeking an alternative to the stranglehold of big publishers in America and Britain over the industry in Australia but they also slip-streamed into five literature grants from the new Australia Council for the Arts in their first year.

This milieu was what enabled Jerrems to publish her work. Schwarz recalls that they knew Jerrems was an outstanding talent her work had appeared in Circus the magazine published by Melbourne University Magazine Society. She has had her first exhibition Erotica in 1972 at Rennie Ellis’s Brummells new photography gallery showing with teacher Henry Talbot.

The other photobook book published in 1974 by Outback Press was on the working class culture of Fitzroy, Into the Hollow Mountains, by Jerrems’s friend Robert Ashton (edited by Mark Gillespie). Jerrems and Ashton held an exhbition of pictures from their respective books at Brummells Photography Gallery in 1975.2

The team at Outback Press had a nose for the coming generation and over the next few years published an extraordinary list of over 100 titles backing then unknown writers, musicians artists, political issues, was extraordinary. They especially championed the New Poets around the La Mamma Theatre in Melbourne.

Mosche Schwartz was Hungarian from a family that fled the communists in the 1950s and came broke, to Australia via Israel. "Just getting each book out was hell," he says. "We didn't have money for eating. But it was fun to create a culture and be at the centre of it.3 For the girls it was perhaps less fun but they were supported.

In 1975 Outback Press published the first anthology of contemporary women poets edited by Kate Jennings called Mother I’m rooted which evidently sold 10,000 copies and her own first book of poems, Come to Me My Melancholy Baby.4 The first phase of partnership lasted till 1980.

In 1995 the National Library of Australia held a seminar called Different Views, Longer Prospects, marking the 20th anniversary of International Women’s Year. In her keynote address Bronwyn Levy noted that "Compared to today, this seems like an almost unimaginable literary landscape - so much has been published, has been written, in the past 20 years. In 1975 we had several books by Thea Astley but none, yet, by Elizabeth Jolley - they were all in the bottom drawer of her desk at that stage seeking publication and we had poetry by Oodgeroo, who was then writing as Kath Walker, but we had no book-length, fictional or autobiographical works by black Australian women".5

The visual arts were as bad and women photographers were not as prominent as they would become in the 1980s.

In A Book about Australian Women Jerrems was listed as teaching photography, drawing, painting and yoga’. She had graduated in photography from Prahran Institute of Art College in 1970 and was one of a new generation of art school trained photographers with a fairly clear and impassioned sense of the role photography could play as social witness.

Even as a student had a stamp on her work saying ‘Carol Jerrems Photographic artist’. She had won the Walter Lindrum scholarship in 1968, the Australian Photographers Award in 1970 and an KODAK students photographic competition in 1971.

Student works by Jerrems were the first by a woman to be collected by the National Gallery of Victoria’s new department of photography.6 Their foundation Curator Jennie Boddington, is quoted in the book as saying Jerrems was "without doubt one of the more important photographers of the younger generation at work in Australia today". She was the first woman photographer shown at the Australian Centre for Photography.7

Only a few images in A book about Australian Women, carried over into Jerrems’s core body of work as exhibited and published between 1975 when her work took off nationally, and her premature death in 1980. The dramatic portrait of blues/rock singer Wendy Saddington (without the Afro hair of earlier years) being the one most reused.

From her next phase of work period Vale Street 1975 is Jerrems’ most famous image It shows a stunning bare-breasted young woman, wearing an ankh symbol charm round her neck. She stands between but forward of, the two ‘toughs’ as like some goddess with her attendant satyrs. It was exhibited at the Jerrems exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography in Paddington in 1976 and was the cover for the 1979 publication Australian Photographers: The Philip Morris Collection.8

Vale Street seemed to many at the time to be the embodiment of I am woman. While the genesis of the image most clearly lies in Jerrems experience assembling and editing A Book about Australian Women, it not portraiture but a complex staged image. The nude model was Catriona [sp?] Brown then an aspiring actor, who agreed to Jerrems’s proposed photographic session in return for prints for her own portfolio.

Arriving at the house in Mozart street, Melbourne where Jerrems lived, Brown found two young ‘sharpies’, Mark Lean and Jon Bourke also invited. Jerrems had met them at Heidelberg Technical College where she taught and used them as actors in a16mm film sequence when applying for an Australia Council grant to make a film called School’s out.

The negatives in the Jerrems archive at the National Gallery of Australia show the session unfolding as Jerrems instructs the boys to take off their tops as well and tries various poses. Jerrems made Vale Street a limited edition of 9 which had reached 7 by the late 1970s.9

As the image grew in fame over the ensuing years Moore was vexed by the ludicrous assumptions made about her by reviewers. Some waxing poetic about the image as a modern form of paganism, imagining lascivious sexual rituals.10 Not that Jerrems who paraded her sexual liberation and openess to experiment, would necessarily disapproved of such a scenario.

Despite the fact that several other images of the trio clothed and looking relaxed were also exhibited Vale Street was taken as a spontaneous documentary photography for some years. The image raises interesting questions about Jerrems position on the prevailing personal documentary photography modes of the 1960s-1970s.

The young photographers of the 70s took a position against photojournalism which they viewed as being just as much commercially driven and controlled by editors as advertising. It was perhaps an unconscious pragmatism on their part ie. quitting what was no longer really an option. Life magazine closed in 1972 and the commissioned work which had sustained photojournalists of the highest aspirations such as Henri Cartier–Bresson, drastically declined.

However, the personal-documentary street photography much valorised and supported in the 1970s by the increasing numbers of art school trained photographers and related publications of art photography subscribed to many notions derived from older photojournalism such as not staging events or cropping excessively.

Jerrems did not on the whole roam the streets on the hunt for pictures She was not a ‘master-thief’ as Cartier-Bresson described himself. She sought an exposure and engagement with subjects including situations of widely different experience and backgrounds.

Some images in A Book about Women (Wedding guests for example) show Jerrems taking side glance at the other great explorer of the fringe the American iconographer of the sixties Diane Arbus. Going in to a pub to photograph is always vexatious, going to a tough pub and photographing Aboriginal drinkers was not a simple street activity. Most of documentary photographers of the era in Australia worked at a safe distance, or from rather formalist concerns in their urban wanderings.

Kathy Drayton writer and Director of the recently released documentary Girl in a mirror, found interviewees gave her a picture of Jerrems as someone who didn’t necessarily relate all that well to women, nor was she an entrenched ‘comrade’. She was seen as a bit of an outsider by those in causes feminism, aboriginal rights or gay rights.11 Jerrems was largely a ‘directorial’ photographer and her forte was to combine of a kind of classic still photography in a documentary tradition with the particularly energetic off-the wall 35mm photographic styles of the 1960s.

The new reflex cameras were relatively affordable and not only introduced a generation of younger photographers to eye-level composition already miniaturised and composed by the reflex mirror. The lenses allowed for foreground close-ups given an emotional closeness to the subjects.12 Jerrems is highly inventive in her deployment of focus as well as placement of figures in succeeding planes of the picture.

In 1980 Jerrems died prematurely of a type of blood cancer, after considerable suffering in her last two years. She had had more than a little measure of success and acclaim but too little to suggest she had made a lasting contribution, or that she would remain fascinating and draw new younger generations to her work with a particular fervour.

In 2001 Sydney documentary film-maker Kathy Drayton saw Jerrems pictures at the World Without End photography exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and was inspired and impelled to retrace Jerrems through her milieu of musicians, film-makers and spiritual questers of the 1970s. Drayton’s film called Girl in a mirror elucidates the communion with people Jerrems sought from the other side of her camera.

In the frontispiece to A Book about Australian Women Jerrems writes in very New Age language: "There is so much beauty around us if only we could take the time to open out eyes and perceive it. And then share it. Love is the key word".

Elsewhere Jerrems made comments about her role in helping a sick society and how she really cared about people. Her body of work is distinguished by its inclusion of the accelerating Aboriginal rights movement. Her early sketchbooks and diaries show a leaning to fantasy and dreams of the girl-child seeking love approval and communion of which she herself felt denied.

Footnotes

- Titles were; ‘Slaves’, ‘Care for one another’, ’Tiger’, ‘A lot of weddings’, ‘Tea’, ‘Great experimentation’, ‘Rape’, ‘Reconciliation’, Frizzle Frizzle Frizzle’ ‘Looking up in search’. Covering sexual preference, discrimination, oppression.

- Information from Manuela Furci, Director, Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive, Melbourne www.RennieEllis.com.au

- Schwartz is active both as a property developer and committed to public catalyst of debate on arts and politics, environment and politics publisher including most recently of the new review The Monthly. Born Mosche in Hungary 1948 his parents fled the communists going to Israel then settling in Melbourne in 1958 He dropped out of architecture and joined three others to start Outback Press in 1973. Chaotically they published Elizabeth Jolley, Morris Lurie, Kate Jennings. "Just getting each book out was hell," he says. "We didn't have money for eating. But it was fun to create a culture and be at the centre of it." After the four parted, Schwartz and Milgrom continuetook Outback Press commercial Susan Wyndham, ‘Developer adds another story’, Sydney Morning Herald 12 June, 2004

See also Interview with Schwartz in Melbourne by James Button, ‘The art of the deal’ The Age March 21, 2004.

- Jennings moved to New York, married designer Bob Cato and was back in Australia in 2002 on a tour in connection with her new book Moral Hazzard.

- Women Writing: Views and Prospects 1975-1995 seminar 18 November 1995 National Library of Australia (link not available)

- The Department was established in 1969. In 1976 Jerrems was the first living Australian woman photographer to have work acquired by the National Gallery of Australia.

- Possibly the first solo exhibition of a woman photographer in an Australian public gallery. Jerrems’s work had been included in the Centre’s publication New Photography Australia in 1974.

- For an account of the Philip Morris collection see Gael Newton, On the edge: Australian photographers of the seventies, San Diego Museum of Art, 199

- From an edition notation on the print selected by National Gallery of Australia Director, James Mollison for the Philip Morris Arts Grant Collection c 1976 and donated with the collection to the National Gallery of Australia in 1983.

- Catriona Brown returned to Australia in 2005 to be interviewed on camera for the Kathy Drayton film, Girl in a mirror. Mark Lean the young man on the right was also interviewed and expressed a certain feeling also of being exploited.

- The film premiered at the Sydney Film Festival 16 June 2005. Producer Helen Bowden, Toi Toi Films. The film drew on the extensive Jerrems still and film negative and prints archive at the National Gallery of Australia donated by the artist’s mother Joy Jerrems in 1983?[ck]

- The new style is discussed well in Martin Harrison’s book on Young Meteors on photojournalism in Britain 1957-1965, 1998

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

More on Carol Jerrems

|