Generations: Australian Photography since the 1970s

Gael Newton

This essay was written in 2002 and reflects the profiles of the artists at that time

|

| Michael Riley, Cloud 2000 |

As I child I used to wonder whether Noah had let kangaroos onto the Ark - and if so how did they get all the way to Australia? Perhaps the Aborigines brought them, but I couldn't see any aboriginal peoples on the Ark either. In the 1920s the Australian modernist artist Margaret Preston solved the problem of putting Australians 'into the picture' by simply inserting both kangaroos and Aboriginal peoples into a print she made of the Ark in an Australian setting.

At ARCO 2002 Australia is the focus country, and as a result Australian artists, dealers and organisations are showing in greater numbers than ever before and can expect attention. Fortunately, ARCO is not the Olympic Games and does not call for parades with banners and coordinating national costumes.

The names in this exhibition, which is an Ark of another kind, are a 'story' in themselves, marking changes in the Australian art scene over the past twenty years. Male and female, Indigenous and non-English-speaking background artists are included, perhaps to an extent not yet achieved within contemporary practice in many of the older western countries. The presence of Indigenous photographers on the stage of contemporary Australian art is taken for granted, more so than that of 'first peoples' photographers in many other western nations.

Contemporary Australian photo-artists have more options than in the past when it comes to being seen abroad, so there is no need for gratuitous kangaroos, gum trees or other well-worn icons of Australia in the mix of works in the Sala de Exposiciones del Canal de Isabel II. Yet in varying ways a number of the artists are engaged in telling and retelling familiar or forgotten tales.

Bill Henson replays (or forecasts?) the apocalyptic in a contemporary vein, while Pat Brassington undermines the homeliness of the everyday with disquieting pictures conjured through digital manipulation. Michael Riley, Brenda L Croft, Polixeni Papapetrou and Deborah Paauwe each weave complex narratives around the inscribing of the child's image of self. Anne Ferran retrieves the forgotten histories of women in colonial society, whilst Martin Walch and Phillip George explore imaginative histories and meanings for the land itself.

The role that photo-based art how plays in contemporary Australian art is widely recognised. Former Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Bernice Murphy chose 4 men and 11 women practitioners for a major presentation of new Australian photo-based art at the Berlin Kunstverein in 2000. Yet as recent as the 1970s photographic practice was dominated by men, and 'photographer' meant either a professional in commercial practice or an amateur exhibitor in specialist photographic venues. The term did not include the concept of the photographer as being in the vanguard of contemporary art.

Throughout the seventies there was a rapid growth in public awareness of photography. Government funding via the newly formed Australia Council for the Arts allowed for the establishment of the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney in 1973 and later the Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne. Meanwhile, museums began to collect and display photography as an art.

Surveys of the period show a preference among selectors for personal documentary and especially street photography in the American mode. Works were usually small-scale black and white and mostly by men, although Carol Jerrems (1949-1980) was regarded as the exemplary figure of her generation. In the 1980s postmodernism powerfully attracted students, in particular women, many of whom sought out art school photography courses as a conscious choice of expressive mode and vocational direction.

The Melbourne photographer Bill Henson has at all times occupied a unique place. From the mid-seventies, well before the tenets of theatricality were articulated in postmodernism, Henson produced emotive romantic clearly staged works that were exhibited as large-scale installations. In the late eighties a new generation of women artists including Anne Zahalka and Anne Ferran emerged in force or, if they had worked in earlier documentary modes, reinvented themselves.

A group of Indigenous artists announced their own presence in 1986 with the first exhibition of work by Indigenous and Torres Strait islander photographers to be shown in Sydney and Melbourne. Tracey Moffatt was a force behind that exhibition which debuted Some Lads, her first photo-series.

Michael Riley, who was to have a dual career as filmmaker and photo-artist was also in the 1986 exhibition showing classically black and white but subversively 'glamorous' portraits of Aboriginal women. He has continued producing across these two mediums, gaining in scale and colour and embracing large themes of national and personal destiny. In this exhibition his acclaimed body of work addresses Indigenous and western spiritual regimes.

In the seventies and eighties photographers were shown in dedicated photography galleries but rarely included alongside painters and sculptors in the stable of major dealer galleries, or even in the publicly funded contemporary art spaces. Bill Henson was one of the few photographers to move easily between photography and contemporary art venues at home and abroad.

|

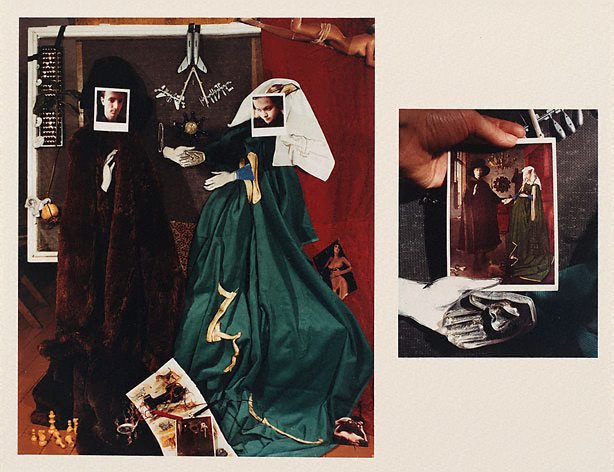

| Fiona Hall, The marriage of the Arnolfini - after van Eyck 1980 |

It was only in 1981 at the first-Australian Perspecta exhibition in Sydney that curator, Bernice Murphy, recognised photographers as contemporary artists. Murphy included an installation by Bill Henson as a major work and also groups of works by Fiona Hall and Douglas Holleley. Hall and Holleley both showed small-scale works, but subsequently in contemporary art shows throughout the eighties and nineties photographic works increased in number and indeed in scale and impact.

The 1982 Perspecta exhibition was also the first major occasion in which recent Aboriginal works were included as 'contemporary' art. Photography was in the slipstream in these years but came to have an ever more prominent role in defining contemporary art in Australia.

However, art presented under nationalist banners can be illusory. Artists today are world citizens and an international style of postmodern and post-photographic approach is apparent when looking across contemporary photo-media practice from many countries. Ultimately artists tend to slip out from under the agreed interpretations offered of their oeuvre in their own time.

When looking at the work of the Australian artists in this exhibition the viewer is also permitted (indeed encouraged) to bypass whatever these works may or may not say collectively about a country and simply to experience and enjoy the rich variety of each individual practitioner's imagery.

At the time of writing this in 2002, Gael Newton was Senior Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia.

Artists mentioned above:

about ARCO 2002

Works shown in the exhibition Australian Perspecta 1981

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|