Harold E. Edgerton (1903-1990)

and split-second photography

Originally published as a brochure for the 1999 exhibition

31 October 1998 - 14 March 1999 Orde Poynton Gallery National Gallery of Australia

Dr Harold Edgerton

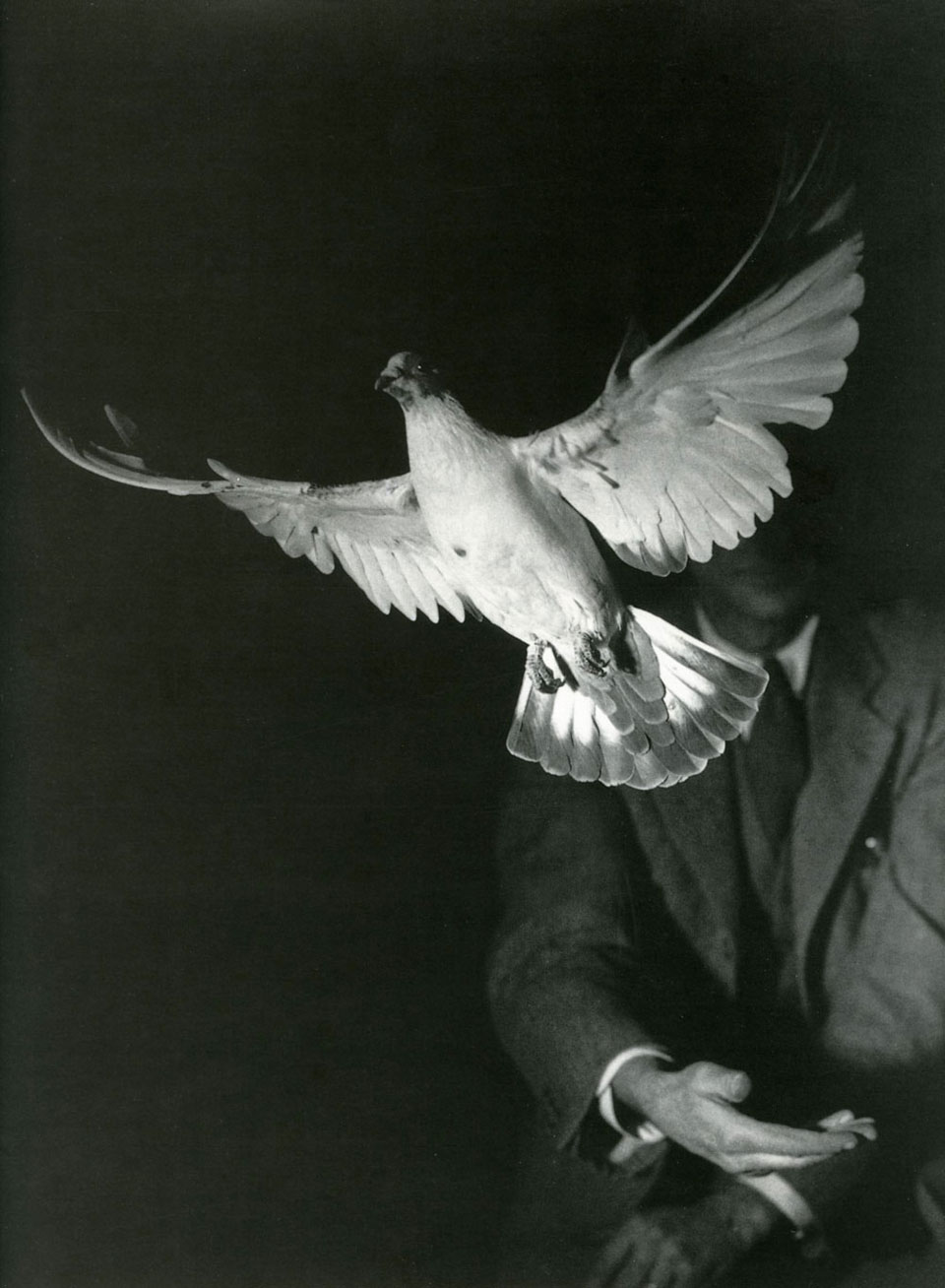

Rising dove 1934 This image was taken at 1/100,000th of a second. Bird flight was a particular subject of study for Edgerton as it had been for pioneer photographers of animal locomotion in the 19th century such as Eadweard Muybridge.

Dr Harold E. Edgerton is renowned as the inventor and developer of modern stroboscopic, or high-speed electronic flash photography1 — whereby intense sparks, like mini lightning strikes, are fired in rapid succession at exposures ranging from a millisecond to one-millionth of a second. The flash acts as the shutter and simultaneously illuminates, exposes and thus captures on film, objects or figures moving faster than the eye or the conventional camera lens can record. The resulting images of motion can be singular frozen-action events or multi-flash composites in which a rapid sequence of movements is recorded on one plate.

Today stop-action photography is the daily fare of newspaper and television sports reportage, but when first published in the 1930s and 40s Edgerton's flash photographs were revolutionary and novel. Most visible movement could be captured on black and white film by the 1930s, but Edgerton's spectacular and stylish photographs of ultra-fast moving figures and objects, motion sequences and collisions taken in thousandths of a second invested viewers with superhuman powers to see an unseen world.

Edgerton's studies were scientific in motive and directed at an understanding of the performance of dynamos and high-speed motors, bird flight, projectiles, fluids and gases, as well as human and animal locomotion. The practical applications went well beyond photography and Edgerton held many patents in his own right. The aesthetic quality of his images also won him considerable acclaim, and Edgerton has a secure place in the history of photography on both aesthetic and technical grounds.

Harold Edgerton grew up in Nebraska and studied electrical engineering at the State University. He completed his post-graduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston and was on staff there from 1927 to 1 968; he continued to teach as Emeritus Institute Professor until his death in 1990. Widely known as 'Doc', Edgerton was the inspiration in 1976 for the off-the-wall scientist of that name in Gary Trudeau's satirical cartoon strip, Doonesbury, whose motto was 'if it moves — it's my game'.

The laboratory and corridor where Edgerton exhibited his studies to generations of students and visitors at MIT became known as Strobe Alley,2 and was so dedicated officially in 1982. MIT's Edgerton Center, established in 1 992 with the help of the Harold and Esther Edgerton Family Foundation, continues his work through strobe based video and still imaging programs and workshops.

While Edgerton declared he was not an artist but an engineer — 'I am after the facts. Only the facts' — he delighted in sharing his enthusiasm for the images of frozen action, and these were much appreciated for their beauty and their novelty. From the beginning he actively promoted his flash images and stroboscopic inventions in his own attractive books, and in magazines such as LIFE and National Geographic. He also accepted the collection and exhibition of his photographs by art museums; and, posthumously, he has been the subject of major museum exhibitions and monographs. These publications rightly record for posterity an important and delightful body of photographic art.

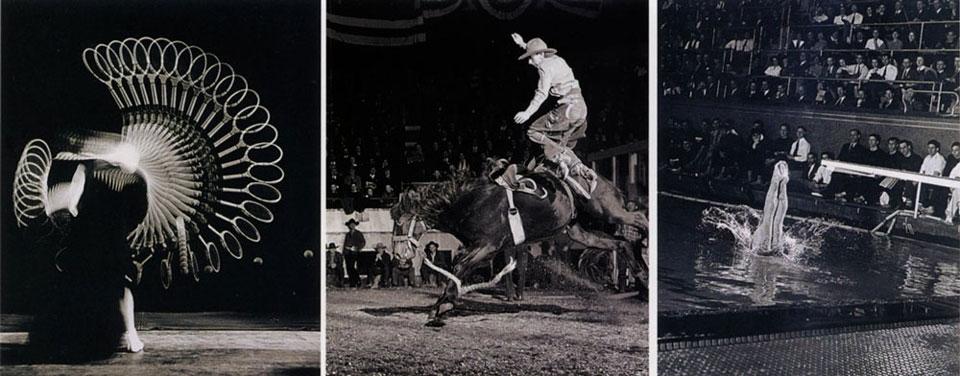

Dr Harold Edgerton, Backhand c.1939 An early use of multi-flash exposure Rodeo 1940 Cecil Henley on Homebrew at Boston Garden Diver 1955

Few accounts of his work, however, pursue a social context for this chameleon who bridged art, science, commercial photography and the popular media. Edgerton was a creative and imaginative image-maker, but his work developed in tandem with scientific, social and aesthetic trends of his time; these factors form the background to his work and give added significance to the images.

A/lore powerful than a locomotive — faster than a speeding bullet — able to leap tall buildings in a single bound: throughout the 1950-60s these lines introduced episodes of Superman on TV. This friendly alien superhero first appeared in comics in New York in 1937-38, at the same time as Edgerton's flash imagery was being published. Nowadays trains, hand guns and skyscrapers have long been superseded as the yardsticks of power and scale, but our century remains indelibly the era of speed, violence and superforces.

From the turn of the century, science had been prising open the secrets of the universe, and technology promised to liberate Western society from natural and human physical limitations. While the total adoration of technology in the early 20th century was muted by the subsequent short hop from fast cars to nuclear fission and the prospect of mass destruction, fantasies of human superpowers delivered by technology live on.

Paradoxically, a cult of the body and physical education was a notable phenomenon in the 1920s and 30s and was allied to technological advance and the reorganisation of society on rational and hygienic lines. The 'gymnast' became a model for the modern super-race. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, striding, leaping, somersaulting and flying figures shown from a dizzying array of viewpoints were a recurrent motif in art, design and advertising. Photography also leaped into the modern age as photographers, both amateur and professional, embraced movement and speed.

Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986), in the first decades of the new century, recorded his family's passion for automobile racing and flying, as well as the pie de vivre of running and jumping. In 1932 Henri Cartier-Bresson (b.1908) made his classic shot of a man jumping a puddle at the Gare St Lazare, reiterating the image of the leaping figure in a dance poster behind. Retrospectively it was to prove too close a hop, skip and a jump from the adoration of athleticism to militarism and fascism, as signalled most infamously in Leni Riefenstahl's film of the 1933 Olympic Games in Berlin.

J.H. Lartigue Grand Prix A.C.F. Circuit de Dieppe - Delange 1912 National Gallery of Australia

Edgerton preferred to describe his capture of the fractions of time as 'events', but they can also be read as cultural artefacts. His seductive images are fun: a balloon and a bomb, a bullet and a playing card are as much slapstick as the images of dancers, divers and tumblers. When his published imagery is considered cumulatively, it is a festive image-circus, mostly awesome, delightful, sometimes emotionally moving, and at times cute and coy. An oft-reproduced self-portrait of Edgerton with an exploding balloon makes of him the court jester or ringmaster of flash photography. Among the most well known of his images is the luscious and fleshy red apple the moment before it disintegrates after being pierced by a bullet. It was first presented in 1964 at an MIT lecture jocularly titled 'How to make applesauce at MIT'.

Cutting the card quickly, another well known 1964 image (with several variants using Jacks and Kings), shows a playing card neatly sliced by a bullet. In looking at these images there are strong associations with the world of children's tales as we recall William Tell and Alice in Wonderland. There are connectors too to the world of Walt Disney animation which was developing to its golden age throughout the 1930s-60s. Cartoon art also developed rapidly through the 1930s and was similarly full of frenetic speed and impossible leaps, jumps, runs and ecstatic but harmless violence.

Dr Harold Edgerton Cutting the card quickly 1964 The bullet travels at 2,800 feet per second, requiring exposures less than 1/100,000th of a second.

National Gallery of Australia

Yet Edgerton's studies were not simply scientific. They include ballistics studies, techniques for wartime aerial reconnaissance and nuclear tests.3 No image is more disturbing than a night flash shot of Stonehenge taken in 1944 for the US Army Air Force as part of an experiment in lighting up targets for night time aerial reconnaissance. Los Angeles art critic Giovanni Intra reads the playing card symbol literally, calling it an 'allegorical regicide', and probes the innocence of Edgerton's ballistic studies so often featuring soft objects:

Why the bullet? Simply because of its speed, a terminal velocity which the shutter has to match? Or is it because the innocent objects on which it wreaks havoc are symbols of absolute defencelessness? Or in the case of the playing card, absolute power.4

Flash! Seeing the Unseen by Ultra High-Speed Photography, Edgerton's first book, was published in 1939; it was reprinted in 1954 with colour plates. This book and others that followed5 introduced flash photography to the professional photographer and the general public alike and were enormously popular and well used. A number of photographers such as Gjon Mili (1904-1984), who worked closely with Edgerton, developed specialised commercial and aesthetic applications of strobe work.

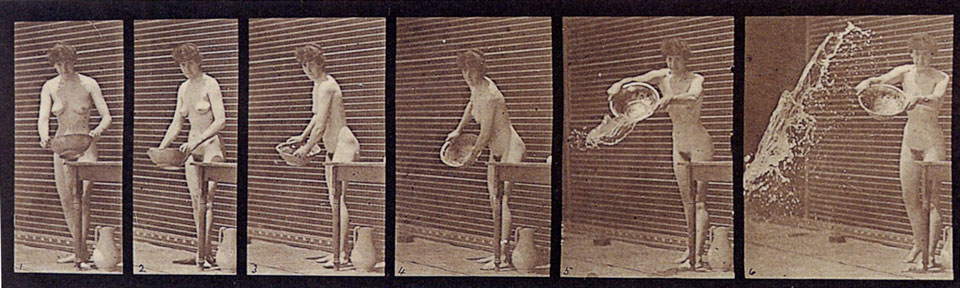

Eadweard Muybridge (1 830-1904) Emptying a basin of water collotype plate 402 from his Animal Locomotion published 1 885-87 National Gallery of Australia

Harold Lighton Dance c. 1940 National Gallery of Australia

Edgerton was aware of, and indebted to his major predecessors in experimental high-speed photography, chiefly: Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) who undertook a commission in 1872 to prove photographically that horses' hooves were all off the ground at high gallop, and made thousands of his own figure studies in 1885-87; Jules-Etienne Marey (1830-1904) followed Muybridge's lead, and in the early 1880s gave the name 'chronophotography' to his own system of recording movement.

Muybridge revealed a world of immense grace and beauty in the simplest of actions, and the sequential grid format has a powerful aesthetic appeal in its own right. His figure studies were often nude (an area not essayed by Edgerton) and provided source material for artists in his own time and into the present day. Significant 19th- and 20th-century artists who were stimulated by these pioneers of stop-action photography include: Thomas Eakins in America in the 1 880s (he also made his own movement photographs); and most prominently,

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) whose famous painting, Nude descending a staircase of 1911-12, derives from sequential movement photographs; the Italian Futurists in the years before World War I who embraced speed and violence as iconic forms of the modern age; and more recently, Francis Bacon (1909-1992) who gave a sharp subjective anxiety to figures of men wrestling taken from Muybridge's studies (seen his Triptych of 1970 in the National Gallery of Australia's collection).

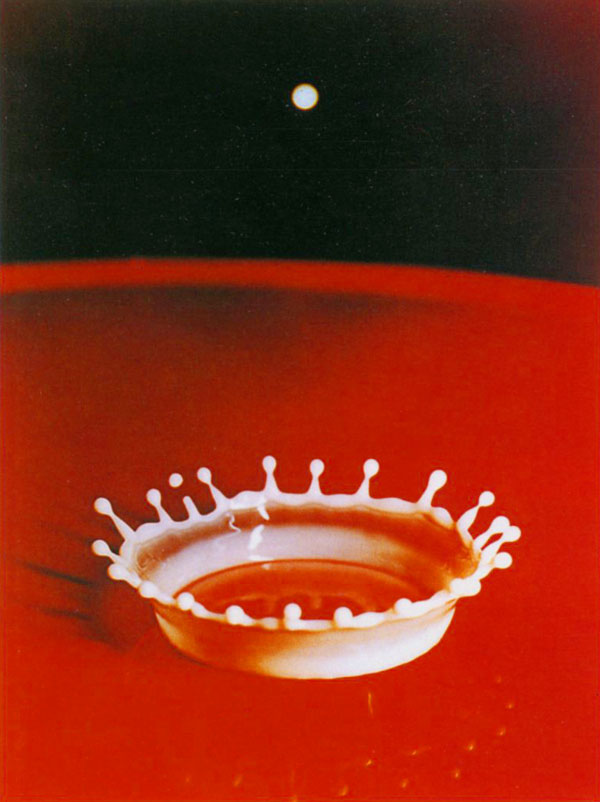

Dr Harold Edgerton 2 images from the Birth of a Milk Drop series 1934 National Gallery of Australia

The three most recognised Edgerton images today are a trifecta of colour studies of objects rather than animate figures or multi-flash images. One of these, capturing the sensuous impact of a drop of milk splashing upwards to form a delicate glassy coronet, has become a much used logo for his work. The first milk drops were made in 1932, and curator Beaumont Newhall (1908-1990?) included one from 1936 under the title Coronet in the Museum of Modern Art's inaugural photography exhibition in 1937.

This was in black and white; numerous colour versions soon followed including the current icon, first made in 1957, where the splash appears to float lotus-like in a crimson lake whose horizon rises to meet a black sky. The incoming pearly droplet is poised above – a parody of a moonrise. Edgerton repeated the shot many times, as did his students, seeking the moment in which the coronet drops were all perfectly formed. Less seriously, the image has a distinct cartoon aura in which a 'froggy' creature's mouth is wide open waiting for the next drop.

Another related colour series was the almost abstract-looking study of milk dropping into cranberry juice to form a glistening rising plume. Surely the rich colour in so many studies is gratuitous in the sense of serving no scientific purpose?

Dr Harold Edgerton Milk drop coronet 1957 National Gallery of Australia One of Edgerton's most famous images from the series.

The paradox of high-speed photography is that the object moving faster than the eye could see becomes an image bizarrely frozen in action like a waxwork. In truth, time is experiential and cannot be stopped, not even when divided into millionths of a second. When we look at photographs, or 'shadowgraphs' as they are sometimes called, it is true that we are seeing the trace impact of light bouncing off 'real things', but time is not 'real' except as something experienced. It cannot be imaged. Photographs are highly artificial and constructed creations. In the act of seeing these photographs, our memories are altered and our culture expanded by what we learn from the way things look as they are photographed. Edgerton's images are a distinct and unforgettable ingredient of our cultural 'pot'.

Gael Newton

Notes

- Edgerton also designed watertight cameras and strobes and sonar devices. He was an associate of Jacques Cousteau from 1953.

- A former MIT doctoral student, Steve Mann, now at the University of Toronto, is also well known on the Internet as an artist involved with the development of wearable computers and a social future as wired beings. He has paid special attention in his own photographs to Edgerton's lab. as he left it prior to renovations, see his site http://wearcam.org/lightspaces. Edgerton Center Home Page, http://web.mit.edu/edgerton/main.html.

- Edgerton's company, EG & G, was initially formed out of a partnership with colleague Kenneth Germeshausen to specialise in stroboscopic applications in 1931 and, in 1934, Herbert Gier joined. The incorporated company was formed in 1947, it supported the Atomic Energy Commission in weapons research and development. MIT has a long history of providing a glamorous, dynamic image to technological developments; and Edgerton provided a model for the way many professors are also media figures — a tradition carried on today by digital age gurus, William Mitchell and Nicholas Negroponte, in the area of electronic communications and computer-aided design. MIT also has a long involvement with the military, see John Burchard Ely and John Wiley, MIT in World War II, Cambridge: MIT, 1 948.

- See Giovanni Intra, 'Report from Los Angeles', a review of the showing in June 1998 of the Edgerton Family Foundation gift to the Los Angeles County Museum, http://www. artnet.co/magazine/reviews/intra/intra9-26-l .html.

- Harold E. Edgerton and James R. Killian Jr, Flash!: Seeing the Unseen by Ultra High-Speed Photography (1939), reprint, Boston: Charles R. Branford, 1954. Later Edgerton books were: Moments of Vision (1979), Electronic Flash, Strobe (1979). Monographs on Edgerton include

Estelle Jussim and Gus Kayafas (eds), Stopping Time: The Photographs of Harold Edgerton, New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1987; Robert E. Bruce (ed.), Seeing the Unseen: Dr Harold E. Edgerton and the Wonders of Strobe Alley, Rochester: George Eastman House, 1994, distributed by MIT Press, Boston.

In 1997 the National Gallery of Australia received a generous gift of 42 photographs by Dr Harold Edgerton from the Harold and Esther Edgerton Family Foundation.

Dr Harold Edgerton's photographs reproduced with the permission of the Harold and Esther Edgerton Family Foundation.

more Essays and Articles

|