IT WAS A SIMPLE AFFAIR

Max Dupain Sunbaker

Gael Newton

Originally published in the Queensland Art Gallery's1998 publication

BROUGHT TO LIGHT: Australian Art, 1850 – 1965

The Sunbaker; / think it's taken on too much ...

It was a simple affair. We were camping down the

south coast and one of my friends leapt out

of the surf and slammed down onto the beach

to have a sunbake — marvellous. We made the

image and it's been around, I suppose as a sort

of icon of the Australian way of life 1

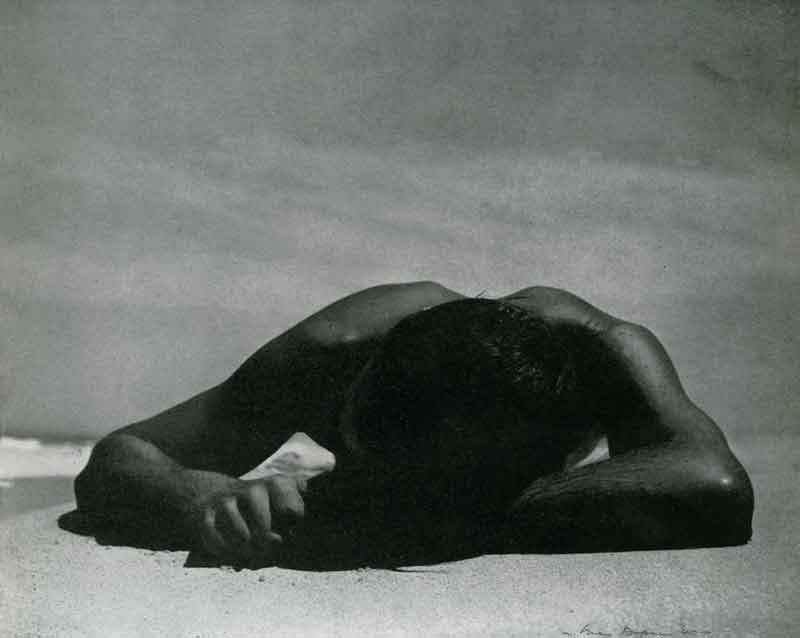

Max Dupain made these comments in 1991 about his best known image Sunbaker (Queensland Art Gallery), which was taken in 1937 while the artist was holidaying on the south coast of New South Wales. Out of Dupain's vast oeuvre dating back to 1929, Sunbaker in particular has fascinated public and critics alike. It is a paradigm of Dupain's own goal of 'Simplicity at all costs'.2

Although the image was rarely seen before 1975, it is probably now the single most widely recognised Australian photograph.

|

|

Sunbaker made its contemporary debut as the poster image for Dupain's first retrospective exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney in 1975.

The clarity and simplicity of the image proved ideal for media reproductions. Over the next two decades Sunbaker was increasingly read as an image of Australia, both past and present.3 It seemed a memento of a less complex era when 'men were men', as if that mighty musclebound promoter of singlets in the 1930s, Chesty Bond, was taking a break between commercials.

When recalling the conception of Sunbaker, Dupain said 'We made the image' but in reality there was no collaborator. Perhaps his comment was a tacit recognition of the way the public claimed the photograph after 1975 and then effected its apotheosis over the next decade — from archival obscurity to national icon.

Dupain was a professional photographer in Sydney from 1934 until his death in 1992. He may have been a little bemused that at the end of his life those 'Holiday shots, the work I've done for pleasure' were worth $850 a print, but he pursued both professional and personal photography with high seriousness.4 |

Max Dupain Sunbaker II 1937

Reproduced from the monograph Max Dupain Photographs, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1948,

plate 7, dated 1940. (see note at the bottom of article) |

|

Despite the phenomenal popularity of Sunbaker after 1975, it was not Dupain's particular favourite. For example, he chose to regularly exhibit Meat Queue (QAG), which had its first exposure in 1946 as part of a story on postwar rationing, and in 1991 he nominated it as one of the few images to still 'have interest for me'.5 Nor was the famous Sunbaker Dupain's first choice out of the two negatives of the subject shot on that summer's day in 1937.

The non-identical twin was published first in Dupain's 1948 monograph, which he described as 'a cross section of my best work since 1935'.6 This preferred version was contact printed for a friend, possibly exhibited in 1940 and 1950, but was never republished and the negative was lost well before the 1970s.

The two versions differ in small but significant ways and their mutual existence as part of Dupain's oeuvre reveals the complexities of photography as an art.

In the 1948 monograph version - above (now known as Sunbaker II 1937), the figure dominates a narrow foreground in the bottom half of the image under a dullish grey sky. The camera has been raised level with the figure so that we can glimpse breaking waves through triangular gaps formed by the crook of the arms. The fingers of the sunbakers right hand grasp those of the left hand and the left arm pillows his head. In this position the harsh overhead sun casts across the face a long shadow which extends into a jagged perimeter around the figure.

It has always struck me as an uncomfortable, even anxious image.

Presumably the images were taken seconds or minutes apart. I have not been able to find out which came first; it was a question I never thought to ask when Max Dupain was alive. What the change in position from one version to the other does tell us is that whilst one image may have been the sort of 'holiday shot' Dupain describes, the second happened under his direction.

Indeed, having espied the potential of the scene, the photographer would certainly have had to alert the subject, his friend Harold Salvage, to remain still. Compared to its running-mate, the monograph version is perhaps a less elegant but more powerful image, given the way the figure's placement in the immediate foreground virtually intrudes into the viewer's space.

|

| Max Dupain Australia 1911-92 Sunbaker 1937 Gelatin silver photograph on paper 39.1x 42.5cm Purchased 1995. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation |

| |

After Dupain's death in 1992, other questions about Sunbaker surfaced. Such was his status as a national treasure in the last years of his life that the mythical process also extended to possession of the iconic images. Following Dupain's death a radio announcer called for an answer to the mystery of the Sunbaker's identity. In fact this information was always available but had been regarded as irrelevant, given the generic title of the image.

It is a well-known phenomenon to curators that people are always declaring themselves or their relatives to be the actual subjects of well-publicised historic images. And so it was with the Sunbaker. Several callers identified themselves as the wanted man, but Harold Salvage's son John was able to produce proof, including another photograph taken by Dupain from a similarly low angle, showing the handsome Harold with an axe over his shoulder.

|

|

The face of the 'real' Sunbaker then made the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald on 1st August 1992. A feature by the paper's 'Heritage Writer', Geraldine O'Brien, was announced by a sensationalist headline, 'Exposed: Max's bronzed Aussie Sunbaker was a lilywhite Pom'.

Clearly there was such a sense of identification with the Sunbaker that the discovery that he was an immigrant was a public disappointment. However, Harold Salvage was quite an appropriate model for the Sunbaker. He was a builder by trade and had migrated from England in the 1920s. Like Dupain he was athletic and the two men shared a passion for rowing and the Australian beach life.7

A solitary, snapshot-sized contact print of the monograph version of Sunbaker II is stuck with no special reverence in an album compiled by Dupain's close friend Chris Vandyke, who was present on the same holiday. The undated album appears to cover at least two south coast trips made by Dupain's circle of friends around 1937-39. The rest of the scenes in the album are typical of the larking about and relaxed activities of beach holidays. |

Max Dupain, Harold Salvage, Culburra c.1937 Gelatin silver photograph From an album assembled c.1937 by Chris Vandyke Courtesy Jill White and Mrs Joan Vandyke, Sydney

(This album has since been sold to the Mitchell Library, Sydney) |

|

However, it also contains more studied compositions including a side view of Salvage showing his face complete with stubble, seemingly taken around the same time as Sunbaker. Here the particularity of the face and the languid reclining pose reveal only too well why the mix of grace, vigour and anonymity works so well in Sunbaker.

The monograph shows a dark print of Sunbaker II dated 1940, indicating that the reproduction had been made from an earlier exhibition print (but the exhibition has not been traced). No vintage prints of either version have appeared despite the widespread publicity about the image.8

It is quite possible that the date '1940' means nothing more than that particular print was made in 1940.

|

| Max Dupain Manly 1938 Bromoil photograph 34.3 x 30.5cm Gift of Max Dupain 1983 Queensland Art Gallery |

| |

Otherwise it is surprising that Dupain should be mistaken about the date of his holiday, given that the years from 1937 to 1940 were marked by major events in his personal life and the world at large. He was married in 1939 to his first wife, the photographer Olive Cotton;9 and it was on another south coast holiday in 1939 that Dupain and his friends learned of the outbreak of war.

By 1941 Dupain was enlisted in the camouflage unit of the RAAF. His war service was continued with work from 1945 to 1947 on assignments across Australia for the Department of Information which was already focused on postwar recovery and immigration. There was little time for exhibiting in these years.

The dark tone of the monograph reproduction of Sunbaker II leads me to see the image as more surreal, perhaps even oppressed by the threat of war. This introspective subject suggests a link back to the motif of the body of the sacrificed Anzac — a feature of much First World War art. However, Dupain's image does not conform to the plethora of nationalistic imagery based on the sunlit beaches and strapping tanned lifesavers which was employed strategically from the 1920s to define Australian identity and to encourage immigration and tourism. The sunbaker does not beckon, stride or salute. There is no hint of the collusion between regimented elements in popular modern design and the marching militarism of the 1930s. It certainly belongs to the imagery of the 1930s in which the body beautiful (and healthy) was a symbol of a new world of strength, vitality and rational modernity, but does not endorse any political platform. Nor is there the jolly, hedonistic abandonment of careless sunbathers, which was a popular motif throughout the period.

In answer to the question of why his works were seen as 'quintessentially Australian', Dupain mused that he was not sure if he or his audiences knew what they meant by that statement. He pointed out that his work was mostly based in New South Wales, but that his Australianness' stemmed from his devotion to his country.

Dupain was a reluctant traveller who left Australia only twice for war or work reasons and was scornful of the fever that took photographers and artists overseas in search of culture and inspiration:

My whole life — if it's to be of any consequence in photography — has to be devoted to the place where I have been born, reared and worked, thought, philosophised and made pictures to the best of my ability.10

|

Page from Vandyke scrapbook showing Dupain (with camera) and friends on holidays at Culburra, 1938,

courtesy Jill White and Mrs Joan Vandyke, Sydney. This album has since been sold to the Mitchell Library, Sydney |

Dupain most frequently stressed that it was his quest for simplicity that was the particular quality in the subjects he chose to present. Yet in his own considerable body of writings from 1935 on, and in the accolades he received in later life, there is also the implication that Dupain's honest, direct (male) response in capturing the images of Australia was in tune with a national identity. On receiving his Companion Order of Australia in 1992, Dupain allowed himself a little long-term ambition in musing that perhaps the pictures were only now 'taking hold'.11

Dupain's fellow photographer and then Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Hal Missingham, was the first to cast the photographer as the visual poet laureate of Australia. He contributed the foreword to the 1948 monograph on Dupain, claiming that, 'When I look back over the last seven years since my return from abroad I find that my memory of the images of our land is made up in great part of the penetrating camera statements of Max Dupain'. Missingham also praised Dupain's images for their movement, a quality seen as particularly photographic, singling out Surf race start, Manly c.1940s as an example. He does not mention Sunbaker II which is also supremely photographic in its tonality and dynamic, but not an action shot.12

Reviewers of the monograph similarly made no mention of Sunbaker II, perhaps for the same reason — it lacked the simple polarities of action or abandon that were associated with the increasing popularity of surfing and beach culture through the 1920s and 1930s.

Much of the appeal of Sunbaker (the QAG version) is in its stillness, but there is also a counterpoint between relaxation and the inherent coiled energy in the man's musculature. The image has simplicity and drama, austerity and sensuality. Within the triangular composition of the central figure/form the flow of angled and undulating lines converge to a central point around the shiny vortex of the man's crown. The sensuous quality of the water droplets on the skin, the rivulet patterns of body hair and sand-tipped fingers have a curious echo of the intense physicality in the slightly earlier still-life photographs of the American modernist Edward Weston.13

Just how Dupain’s spontaneously snatched vision on the beach came about is a little less simple than his comments suggest. If we begin by looking at the moment of exposure, we can dismiss the idea of Sunbaker as a lucky shot.14 This was the work of a professional photographer, albeit one on holidays. It was taken on a Rolleiflex, not a Box Brownie, and its striking triangular composition clearly points to the aesthetic intention of the artist. Every beach-goer has probably witnessed a similar event, but few are vision – and camera-ready as was Dupain.

Sunbaker had to be shot at ground level, and, as sand is anathema to cameras, the image had to be made with care. The harsh lighting conditions needed a professional's understanding of exposure — how much to give to record both the enormously bright and reflective sky, sea and sand and the tonal details of figure and shadows. The contrast in light encompassed in the subject is made clear in the contact print off the surviving negative. In printing, the sky and beach have to be 'burned in' with extra exposure. The contact print reveals the accuracy of Dupain's exposure and the acuity of his eye; the exhibited version is virtually the full negative, with cropping restricted to the foreground largely to remove a dominating shadow and to make the image a horizontal rectangle reflecting the form of the subject.

The unusual perspective of Sunbaker is also well outside the average photographer's imagination or technical expertise. The subject (who has no messy towel to disturb the austerity of the image) is seen from somewhere slightly below the plane of the figure. This worms-eye vision is not a natural choice but endemic to the conceptual vantage points favoured in modernist photography in the 1920s and 1930s. New Photography revelled in rendering the everyday world through the use of strange, low, oblique, and close-up views.

The figure in Sunbaker also embodies the counterpoint of energy and stasis evident in classical Greek sculpture. Dupain used his father's miniature reproductions of the famous Discobolus and Venus de Milo in a number of works over his early and late career. He provided illustrations for his father's books on physical education and health (he once posed as The dying Gaul) and made frequent references to sculptural qualities in his works. Of course, classical busts and figures were a recurrent motif in surrealist art and Dupain's work in the 1930s was stimulated to passionate expression by this modern movement.15

Just as the presentation of the figure in Sunbaker is transformed by the choice of a dramatic camera angle, the setting is also recast as an empty and timeless space — a surreal space. This intense privacy in open space is part of the experience of sunbaking, combining elements of exhibitionism and introspection. Those familiar with beach life find the image evocative. We hear the thud of body on hard sand and know the feel of sun, salt and sweat. But there is no story in Sunbaker as such (though some viewers imagined the swimmer had collapsed after perils at sea), not even the cleverness of much 'decisive moment' photography.

Expatriate Australian critic Geoffrey Batchen has teased out the paradox of the image in which:

[the] symmetry also works to draw the viewer's eye into the black void at the centre of the picture, adding a menacing sexuality to its sense of dynamic implosion. In short the Sunbaker is one of those images that fascinates because of its ability simultaneously to attract and repel the gaze.16

At the time of making his picture Dupain was 26, athletic and handsome, just like the Sunbaker. After only three years in the business he was the most publicly profiled professional photographer in Sydney, not in the old model of exclusive, upper-class society and viceregal portraiture, but in the new world of commercial and editorial photography. Dupain actively exhibited his personal work in local art photography and professional salons from 1932, and his work also appeared in Art in Australia and The Home magazine under the patronage of art publisher Sydney Ure Smith.

Ever innovative in art publishing, it was also Ure Smith who chose to make a monograph on Dupain in 1948 as one of the photography-based publications that announced the postwar recovery. It was an expensive production limited to one thousand copies. For the monograph Dupain (probably in collaboration with Ure Smith) chose his 'best work', but the surrealist works and fashion assignments were gone. This was a sober, postwar world and Dupain had come under the influence of the philosophy of filmmaker John Grierson whose term 'actuality' Dupain used to describe his own documentary work.

|

| Max Dupain Anzac Square c.1940-45 Gelatin silver photograph on paper 40.7 x 39cm Purchased 1992, Queensland Art Gallery |

| |

Dupain's vision sought a reductive but dynamic clarity as if this quality was a bastion against the confusions of other aspects of the world competing for attention. Dupain's goals were for simplicity but his aesthetic was complex in its understanding of how actuality related to the wider notions of documentary photography.17 On a personal level, across Dupain's work, the motif of a lone male figure can be found, even in a crowd; in some cases, as with Anzac Square c.1940-45 (QAG), these figures are stalked by deathlike shadows. Like Dupain, who was agnostic and republican in spirit but not active politically, this alter ego is not one of the herd.

Is Sunbaker autobiographical in the sense of expressing the artist's own sensitivity and aloneness or a counter to the images of jingoistic 'blokes' in the popular media?

The text that Dupain contributed to the 1948 monograph makes considerable claims for the meaning of the images:

Many people will, I hope, derive ideas from them and some no doubt will be 'amused', but that is not my intention nor ambition. Modern photography must do more than entertain, it must incite thought and, by its clear statements of actuality, cultivate a sympathetic understanding of men and women and the life they create and live. I profoundly believe it can accomplish this.18

In his commentaries Dupain tried to articulate how photographs resolve the objective and the subjective, the fortuitous and the expressive — not such a simple affair after all!

|

| Max Dupain Sunbaker II 1937 |

| In the original publication the above image was reproduced as the one from the monograph Max Dupain Photographs - published by Ure Smith- this is not correct - this version is from the from Vandyke scrapbook - with Max and friends on holidays at Culburra, 1938. We have inserted the correct version of the image at the top of this article. |

Footnotes

- From a transcript of an interview between Max Dupain and Helen Ennis at Dupain's home at Castlecrag, New South Wales, 1 August 1991, p.10 (artist file, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra), published in Max Dupain: Photographs [exhibition catalogue], National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1991, p.18.

- Max Dupain, 'Why they photograph buildings' [exhibition review], Arts Review, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 1985, p.47.

- Sunbakers early appearances were on the front cover of Light Vision, vol.1, no.5, May-June 1978, and Creative Camera Annual, 1978. The caption in Max Dupain's Australia (Viking, Ringwood, Vic, 1986, p.106) reads, 'The sculptural form and weightiness of this figure has become a life symbol for many Australians for whom sun, sea, the beach and the body are synonymous'. In the 1970s, Sunbaker was often mistaken for a contemporary image. It blended easily with 1970s beach photographs and appeared without incongruity in 1979 on the back cover of a major catalogue showing new photographers. Readings of either of the Sunbaker images are also made more complex because in the prints of Sunbaker made since the 1970s the image is brighter in tone and spirit, indeed closer to the quality of Australian light, than the reproduction suggests was the character of the original print. Later printings of the image (of which there are perhaps 100-200 made between 1975 and 1992) have slightly different croppings and tonalities, especially regarding the placement of the horizon.

The familiarity that Sunbaker now contains is such that it has been the model for a dozen or so re-enactments for art and advertising purposes including, most recently, its use as the source for Andrew Stark's banner of The Republican newspaper in March 1997 and also the brilliantly abstracted calligraphic motif in Ken Done's painting Sunbakers II 1995. Done picks up on the correspondence of the figure and the outline of Uluru and renders it in the energetic daubs of Aboriginal art. Refer reproduction of the Done painting in Art and Australia, vol.34, no.3, Autumn 1997, p.294. The earliest of the restaged versions was by Anne Zahalka in 1989. Her colour photograph The sunbather, no.2 (QAG) shows a fair skinned, slightly built figure with long reddish hair occupying the masculine territory

previously claimed by the Sunbaker. The restaged versions of Sunbaker frequently wrestle with the way the image, in its public role as an icon of Australian identity, excludes others by gender, race, sexuality or age from the national picture.

- Max Dupain, quoted (p.26) in Craig McGregor, 'The Devil in Dupain', The Good Weekend, Sydney, 9 November 1991, pp.24-9.

- Ennis-Dupain interview transcript, p.8.

- Max Dupain, 'Some notes about photography', in Max Dupain, Max Dupain Photographs, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1948, p.12; tot Sunbaker II see plate 7.

- The effects of the Depression possibly accounted for Salvage's other occupation as owner/manager of the Craftsman Bookshop in Sydney. It was here that Salvage probably met Dupain who at the beginning of his career looked eagerly to publications from overseas for stimulus — even if he was to spurn visiting the old world in later life. The two men shared interests in architecture and reforms of various kinds. After the Second World War Salvage formed a construction firm, Architon, which constructed Vandyke Brothers prefabricated houses for the Department of Works at Bass Hill and for the Warragamba Dam and Snowy River scheme construction teams. He and Dupain remained friends until Salvage died in 1990.

- Sunbaker is listed as catalogue no. 17 in the Institute of Photographic Illustrators exhibition at David Jones Art Gallery, Sydney, 23-28 October 1950, but there is no way of knowing which version was exhibited.

- The couple separated in 1941. Cotton does not recall being on the particular excursion to the south coast (information from Olive Cotton to the author, March 1997). Dupain married Diana lllingworth in 1944.

- Dupain, in transcript of Dupain-Ennis interview, 1991, in Max Dupain: Photographs [exhibition catalogue], p.18.

- Australia Day Honours lists, Australian, 26 January 1992, p.15. This accolade was used repeatedly in media reports following the announcement of Dupain's Companion Order of Australia award on 26 January 1992 and his death on 27 July 1992; for example, see Geraldine O'Brien, 'Exit an old master', Sydney Morning Herald, 30 July 1992, p.1; Dupain's obituaries frequently cast Dupain as a master photographer who visually defined Australian identity.

- Interestingly, in the sequence of plates in the monograph, which begins with a young boy and ends with a rooster, men tend to be shown as active and women as passive subjects; see Hal Missingham, foreword, In Dupain, Max Dupain Photographs, p.7. Missingham was also a graphic artist and was Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales from 1945 to 1978. In 1946 he had made a dramatically angled study of his young son David, as a sprawled nude on Wheelers Beach, entitled Sunbather (reproduced in Gael Newton, Silver and Grey:Fifty Years of Australian Photography 1900-1950, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1980, plate 79).

- Dupain saw relatively few examples of Weston's work before the 1950s. They shared a common influence from the vitalist philosophies of the 1920s and 1930s.

- See Dupain's comment on At Newport 1952: 'I made several rapid exposures of this scene as the lad began to climb out of the baths. I wound up with this linear, sculptural form — the luck of anticipation', in Max Dupain, Max Dupain's Australia, Viking, Penguin Australia, Ringwood (Vic), 1986, p.157 He made similar comments about Surf race start, Manly c.1940s on p.144: 'One shot only — I had to be lucky and I was'.

- Refer to Christopher Chapman's essay 'Surrealism in Australia', in Surrealism: Revolution by Night [exhibition catalogue], National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, c.1993, pp.216-301, and Ken Wach, 'Max Dupain and the Surrealist Vignette', seminar paper for 'Slip, Slop, Slap, Max Dupain's Sunbakers', National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 16 November 1991.

- Geoffrey Batchen (p.349), 'Max Dupain Sunbakers', History of Photography, vol.19, no.4, Winter 1995, pp.349-57. The important issues on the nature of photography in Batchen's account cannot be dealt with here.

- Refer Max Dupain's Australia, p.19. Dupain frequently acknowledged his teacher at the Sydney Art School, Henry Gibbons, as the source of his own understanding of simplicity, form and movement as the keys to pictorial art. Gibbons also stressed the role of the foreground.

- Dupain, 'Some notes about photography', in Dupain, Max Dupain Photographs, p.12.

Gael Newton

more Essays and Articles

|