The Photographer's Model: Max Dupain's Sunbaker 1937

Gael Newton

paper for a seminar at ANU on Sport and photography run by David Headon circa 1990s

|

| Reproduced from the monograph Max Dupain Photographs, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1948, plate 7, dated 1940. |

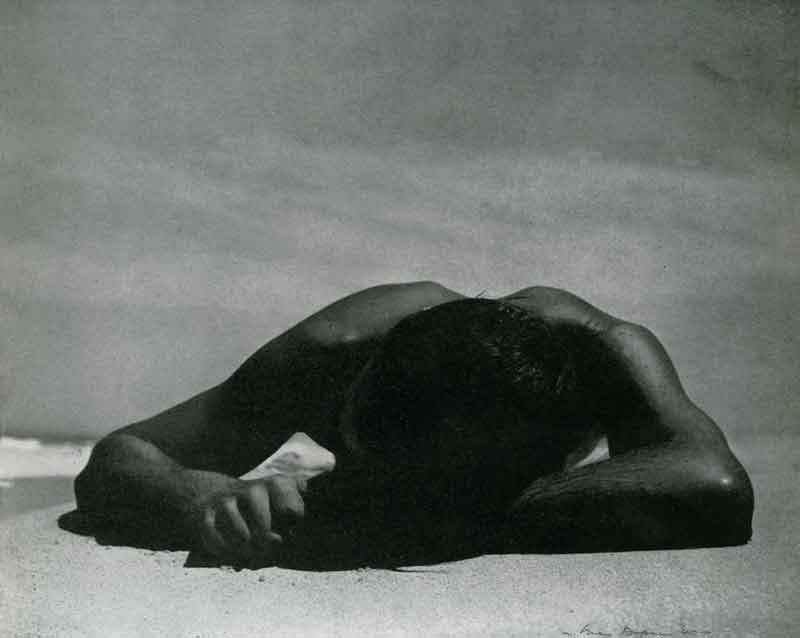

In 1937 whilst on holidays at Culburra on the New South Wales south coast, Max Dupain a Sydney professional photographer, made at least two exposures of a friend and member of the camping party. Dupain's preferred composition Sunbaker I shows the fingers of the right hand clasping those of the left. It was this version which was published in 1948 in a monograph on Dupain published by his friend, mentor and patron Sid Ure Smith.

Dupain described his hopes for the medium in his contribution to the monograph 'Some notes about photography':

Nearly all the photographs in this volume have been made with the intention of securing a fragmentary impression of passing movement or changing form; in the portraits and figures particularly I have tried to save the nonchalance and spontaneity of the mood. Photographs of water, land and 'found things', where the motion has been slow, have been more carefully studied, perhaps too much so, and an appropriate viewpoint and moment of exposure been pre-selected. This little collection is a cross section of that which I consider to be my best work since 1935. Many people will, I hope, derive ideas from them and some no doubt will be 'amused', but that is not my intention nor ambition. Modern photography must do more than entertain, it must incite thought and, by its clear statements of actuality, cultivate a sympathetic understanding of men and women and the life they lead and create and live. I profoundly believe it can accomplish this.

|

| Max Dupain Sunbaker 1937, printed c.1975, gelatin silver photograph 38.6 x 43.4cm, National Gallery of Australia |

No other publication or exhibition of Sunbaker 1 is known and by 1975 the negative was lost. For Dupain's first retrospective at the newly formed Australian Centre for Photography in 1975 new prints were made from the second negative with fingers outstretched and the horizon line higher. Sunbaker II was used as a signature image for Dupain's retrospective and, despite its thirty -eight year vintage, was also featured on the back cover of an influential catalogue of the time on 'contemporary' Australian photography!

Sunbaker thus began its belated evolution as Dupain's best-known image culminating in its current status as an icon of Australian photography but also as an image of nationalism.

It is now most often used as if it encapsulates the optimism and energy of the thirties so quenched by World War II. It is as if the sunbaker is none other than Chesty Bond himself in between surf races. Indeed a certain real disappointment followed on from the revelation in the newspaper in 1992 that the subject was in fact a visiting Englishman and not a genuine bronzed Aussie.

In the last few years of his life Dupain, who was born in 1911 and died in 1992 was made into a national treasure. An endless stream of profiles were published and attention came from many quarters beyond the world of professional photography or art. Honours were awarded to Dupain throughout the 70s and 80s and culminated in the 1992 Companion Order of Australia, the equivalent of a knighthood, for his services to the visual arts. Such treatment is common for statesmen, sports achievers and luminaries in the traditional arts and letters but it was the first occasion in which a photographer had been so honoured.

Dupain's image of the Sunbaker succeeds formally because of its counterpoint of simplicity and drama, austerity and sensuality, relaxation and reserved power. However, I suspect that the particular resonance it has for the public is amplified by the aura of Australian sports and the fervent nationalism that seems to be the driving force rather as much as the outcome of athletic achievements.

One of Dupain's last commissions was to photograph a number of prominent sports people and I do regret that I have been unable to relocate the images but as I recall his portraits were published and sold (in reproduction) through a newspaper for some charitable cause. As I cannot show them it is unfair to state my view that the images were among the least successful in his long career. Perhaps this was age (he was in his eighties but his had not stopped him making superb late still life studies) but I believe Dupain was also uncomfortable with the nationalism such a project implied.

He was consistent even persistent in his efforts through sixty years to have his work seen but distrustful of hoopla, ego and self importance. It once struck me that as a character he would have made a good Diogenes searching for an honest man. In late life his frequent refrain 'What will it all matter in a five hundred years!' became an urgent and uncomfortable demand to those around him as he refused to play the role of charming benign old national treasure demanded of him by the media.

David Headon's proposition that I might contribute a paper to this conference on art and sport has provided an opportunity to bring into focus a little known aspect of Dupain's life and work; his own involvement with and attitude to athleticism. I should state right now that I am indebted to Clare Brown who is writing a biography of Dupain for the information concerning his father George Zepherin Dupain. The role of Dupain's father in the history of Australian sport deserves attention and perhaps this conference might lead to some appropriate acknowledgment.

George Zephrin Dupain was born in 1882 and died in 1959. As a young man in 1900 he founded the Dupain Institute of Physical Education and Medical Gymnastics in his Ashfield Home. Such was his zeal for a scientific management of physical culture that the home became known as ‘The Tabernacle’. The gymnasium was moved to Daking House then Manning House and was run after Dupain's retirement by John Craig until 1982. Through the Institute some of Australia's sporting greats received training including Michael Grayson, James Hardie and Evonne Cawley.

Like many a young man at the turn of the century George had turned away from religion and embraced science as the key to the life and ethics. He was imbued with a missionary spirit evident in many areas of rational reform which to the foundation of modern practises in health and fitness. As with any quasi-religious mission there was also a crank side with advocates of dress reform including one gentleman in Sydney to campaign about health whilst dressed in a Greek toga. Dupain senior attested to his own physical health by posing in toga as the Dying Gaul and using such photographs by his son for illustrations in his publications.

It is to be remembered that the turn of the century saw the wider public become acquainted with the theories of Freud and the idea that repression causes illness. New theories of the relation of a healthy mind to a healthy body were promoted with some advocates believing all social and psychological problems could be cured by regulation or liberation of the body.

George Dupain would have liked to have studied medicine and had he had a higher professional qualification more attention might have been paid to his books which included; Brain and Physique of 1907, Diet and Physical Fitness as well as Curing Constipation Naturally in 1934, Baffling Obesity in 1935 and Elementary Dietetics in 1940. He also published a short-lived quarterly in 1912.

Dupain senior followed the Alexander techniques of body/mind therapy and had an interest in para-psychology. As a young man Max Dupain frequented his father's gym and took photographs for his publications

Max Dupain showed no aptitude for academic learning and only stayed on his last year at Sydney Grammar to continue in the rowing team. Perhaps his lack of interest in the academic side of his father’s business also meant that Max was not suited to take on the Gymnasium. George must surely have been disappointed that his only child would not extend his life’s work in advocating physical health as a moral and social benefit. He left in 1930 and entered an apprenticeship with Sydney commercial photographer Cecil Bostock, later going out on his own in 1934. Dupain's subsequent career in fashion, advertising, portraiture and architecture cannot be dealt with here.

Max Dupain maintained his athleticism after his schooling by swimming and sculling. He remained an attractive and athletic until illness in his eighties. Such was his aura of strength that it came as a surprize to all, and himself, that he did age. By temperament organised sport would have not appealed and his rigorous professional schedule being dependent on weather conditions for the most part would have precluded any form of sporting commitment.

Dupain's physical fitness was grounded in his tutelage by his father. Whilst his father’s work was modern in its application of scientific style principles the model of future athletic health was based on the harmony felt to be evident in the art and culture of classical Greece.

George Dupain had small statues of Venus de Milo and the Discobolus which he used for paired illustrations on the gymnasium letterhead. Max Dupain used these figures in a number of photographs from the thirties to the 70s. They were however totally reconfigured and cast as the figures of an alienated surrealist psychology or introspection.

In looking to the model of Greek art Max Dupain was also participating in a widespread identification in the thirties of the modern spirit with the pure art and culture of ancient Greece. The Life Saving movement was pioneered in Australia in the 1920s and the resplendently Greek god life guard emerged as a metaphor of Australian manhood and virility. The merging of nationalism and the lifeguard can be seen in this poster for the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge symbol of all that was rational and modern.

Striding figures were a part also of social engineering of the time used equally by communists revolutionaries and fascists as well as mere antipodean modernists. Sports and athleticism fulfilled many more functions than mere good health. In Australia the youthful athletes also represented notions of Australia as a young country with its future all before it and free from the corrupted and tired cultures of the old world.

To go back to Dupain's statement in the monograph. A number of contradictions or counterforces are set up in the text and are illustrated in the image of the sunbaker. There is a sense both of the 'securing of a fragmentary impression of passing movement or changing form' and the 'nonchalance and spontaneity of the mood' but also of the pre selection of an appropriate viewpoint and moment of exposure. But what are the thoughts which Dupain believed such 'clear statements of actuality' could 'incite 'and how could such images 'cultivate a sympathetic understanding of men and women and the life they create and live.'

Was this the conventional sporting and outdoor life which Australia’s climate favoured and which through the thirties was used to promote Australia. For such purposes a recumbent figure is rare since it speaks of hedonism. Few images in Greek art are similarly of such positions. The Greek gods must fix their eyes upon their purpose and the ubiquitous lifesaver would not be shown asleep on duty!

The image of the sunbaker does speak of an identification with the land and the strength of the bond to land. The figure is monumental yet sensuous with water droplets still glistening. It is a moment which most Australians can identify with and evoke for themselves at least prior to the ‘Slip slop slap campaign’.

Yet for me it is the opposite of the Lifeguard. The figure is faceless and even introspective for all it’s being at rest the figure seems tense and ready to run. Dupain made many images of figures on the beach ranging from the surreal to the seemingly celebratory yet so often there is no contact with or between the figures they are often loners. Here for all that the lifeguards look like they have sprung off the pediment of the Parthenon the focus is on a lone figure and here in a view of Manly from 1939 our swimmer darts away from the crowd. Elsewhere similar images focus on the lone figure.

In Sunbaker we also have a curiously deserted landscape almost like a surrealist scene (Dupain was deeply affected by the European surrealist photographer Man Ray whose book he encountered in 1935). Our hero is bronzed to the point of having become a native due to the manipulations of the print what was a happy sunny scene is recast and collects some of the darker undertones of the generation aware of the looming world war.

A subject of great curiosity has been Dupain's clear dating of the print 1940 in the print of Sunbaker I illustrated in the monograph. Perhaps the darkness of that print if made in 1940 reflected the cloud hanging over young men’s lives or if made around 1947 for the book, Dupain’s own war experience in New Guinea in the camouflage unit. Dupain was a pacifist and the camouflage unit enabled him to serve.

All the contradictions covered in Dupain 's ‘Notes on Photography’ are present in the Sunbaker; it remains a simple ‘fragmentary impression of passing movement or changing form’ but one which on closer consideration also ‘incites thought’. Art perhaps unlike sport engages with the dark side.

Gael Newton

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|