MAX DUPAIN

the 2017 online version of the 1978 essay originally published in Light VISION 5 *

Max Dupain's involvement with photography began in 1925 at age fourteen, with the proverbial kind uncle's gift of a Box Brownie. A demonstration of processing in the laundry cum darkroom followed, and the lad became convinced that he would become a photographer.

Mr Dupain senior was a well known author and pioneer in the field of physical education and nutrition, who operated a gymnasium in Sydney.

At Sydney Grammar School Max Dupain distinguished himself chiefly in athletics and rowing, as well as by winning the Carter Memorial Prize for Productive Use of Spare Time, presumably for photography.

In 1930 he began work as an apprentice in the studio of a leading Sydney commercial photographer, Cecil Bostock (1884-1939), a gifted but strangely disturbed and contradictory man.

Bostock was a member of the elite Sydney Camera Circle, a small group of pictorial photographers led by Harold Cazneaux; (1878-1953). It was devoted to raising the standard of artistic photography and membership was by invitation only. The Circle had been formed in 1917. |

|

|

| |

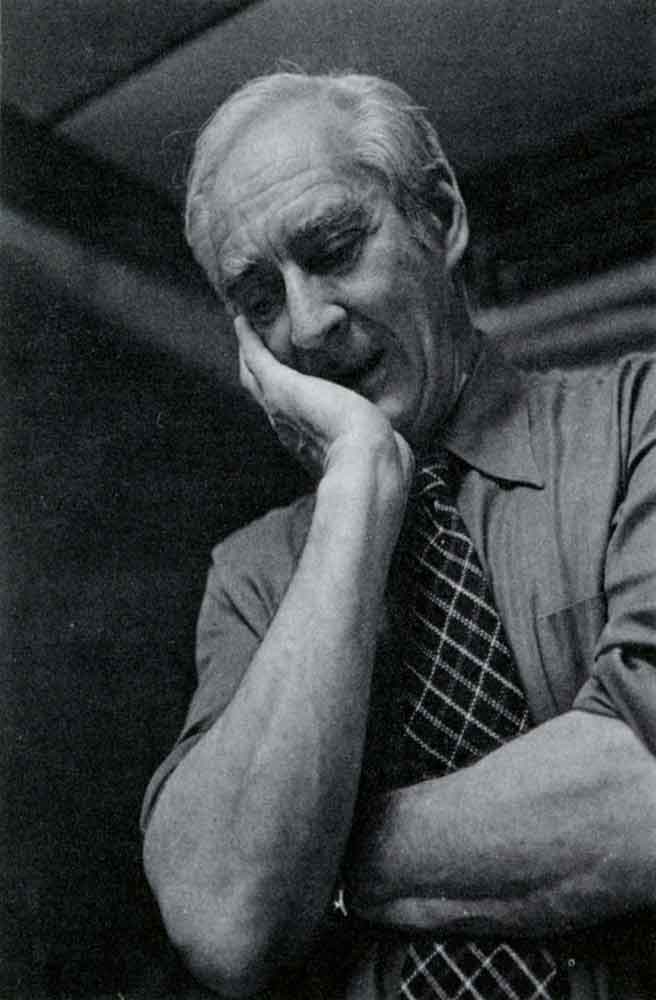

Photo of Max Dupain by Athol Shmith 1977 |

In the same year, Bostock had produced a limited edition 'Portfolio of Art Photographs,' which reveals a preference for straight photography, rather out of keeping with the soft-focus romanticism favoured by his contemporaries. Though a great craftsman bookbinder and decorative artist, Bostock's photographs were realistic and direct, but tentative and rather weak in design.

The engineering firm of Mauri Bros and Thomson was one of the studio's clients, and the problems of industrial illustration intrigued and challenged'Bostock's ingenuity. He was perhaps responding to the European vogue for machine aesthetics emanating from the Bauhaus design school.

At the time of joining Bostock's, Max Dupain worked in the current pictorial style; this meant doing graceful studies of such limited subjects as ti-trees silhouetted against the dusk. The plumber installing the young Dupain's home darkroom had introduced him to the New South Wales Photographic Society, providing him with an opportunity of displaying his early work, which was assured and direct.

During his four years with Bostock, Dupain learnt of the work of the radical Europeans such as Man Ray, Hoholy Nagy and Hoyningen Huene, and of the documentary work of Dorothea Lange, Eugene Smith, Walker Evans, Brassai and Brandt.

The depression, the social ideas of the post war reformers and the fervent embrace of a machine age must have been influential in luring Max Dupain away from the pictorialists and their superficialities, a departure which first appears in his industrial studies around 1932-33.

In 1934 Dupain moved into a studio of his own in Bond Street, Sydney, doing the great variety of assignments that were essential then to survival as a commercial photographer. David Jones department store became a client. This involved mostly fashion and good advertisements, many of which were also done for the prestigious 'The Home' magazine. Since its appearance in 1920, 'The Home' had generated a stimulating climate for photography of all kinds, largely due to the support of its editor, Sydney Ure Smith. Dupain's work for 'The Home' shows experiments with technique and approach, often inspired by Man Ray and surrealist imagery. |

|

|

Contemporary life, sport and recreation form another large area of work at this time, though these he explored for formal possibilities rather than documentary interest. Portrait studies of the 'stars' of the day — ballet dancers, musicians, artists and socialites — was a flourishing genre at this time.

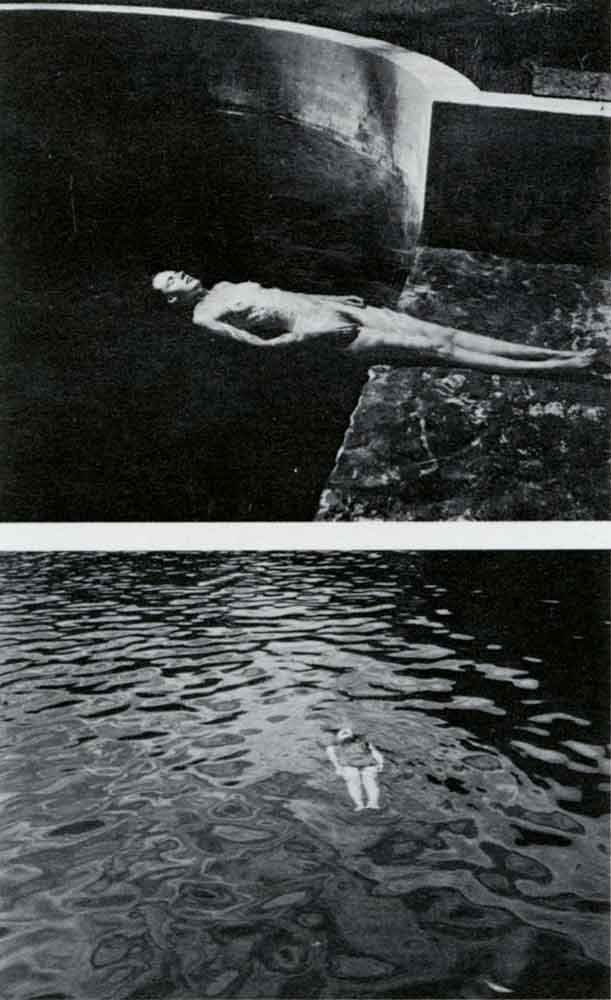

In the illustration work in the years up to 1939, Max Dupain's characteristic formal concerns emerged more clearly — direct, effective and dramatic with an interest in peculiar intersections of space and geometry. Some images are startling and unexplained by simple evolution, such as one of two girls' legs (1935) which may owe something to Man Ray, but is also a key to later work.

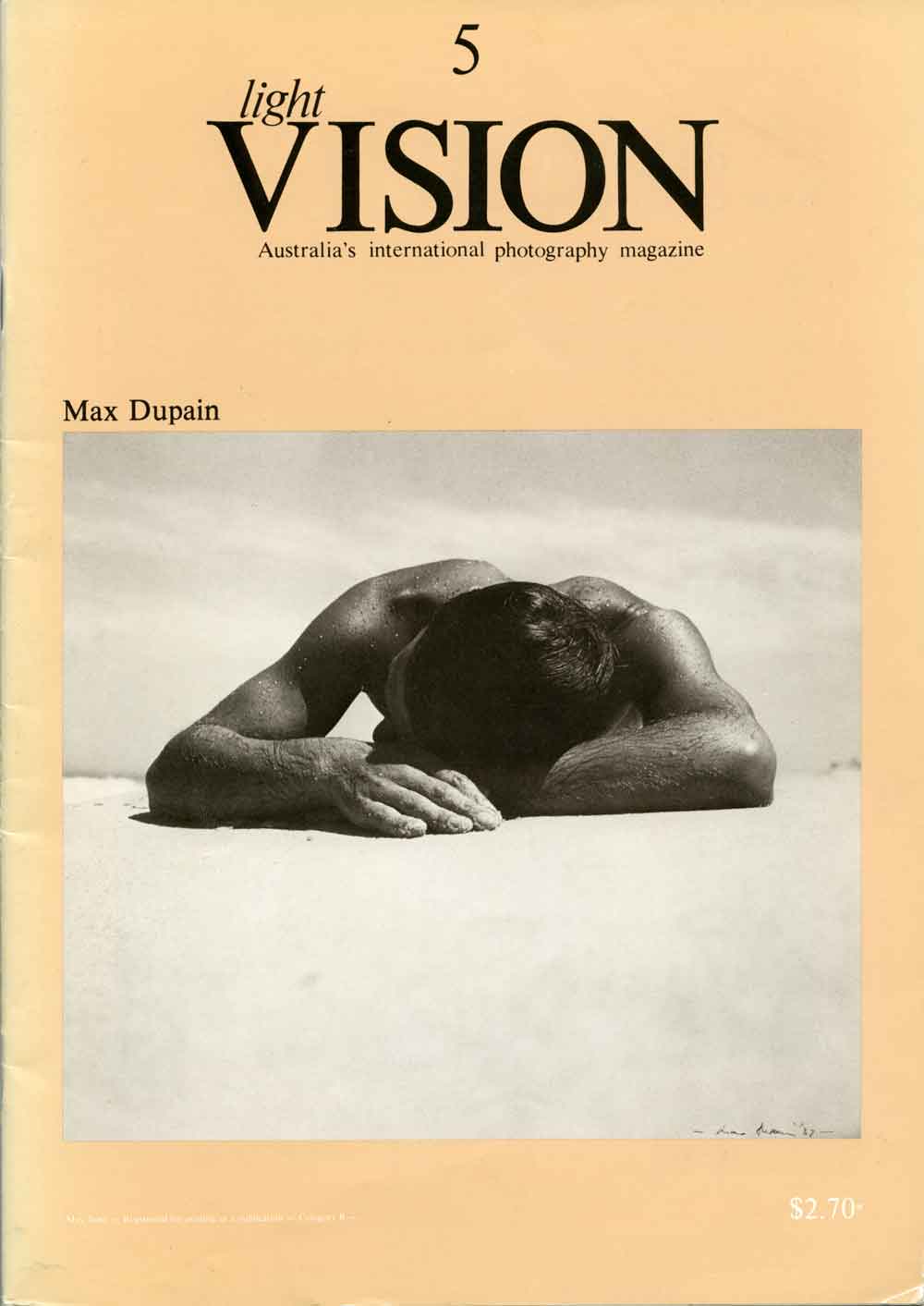

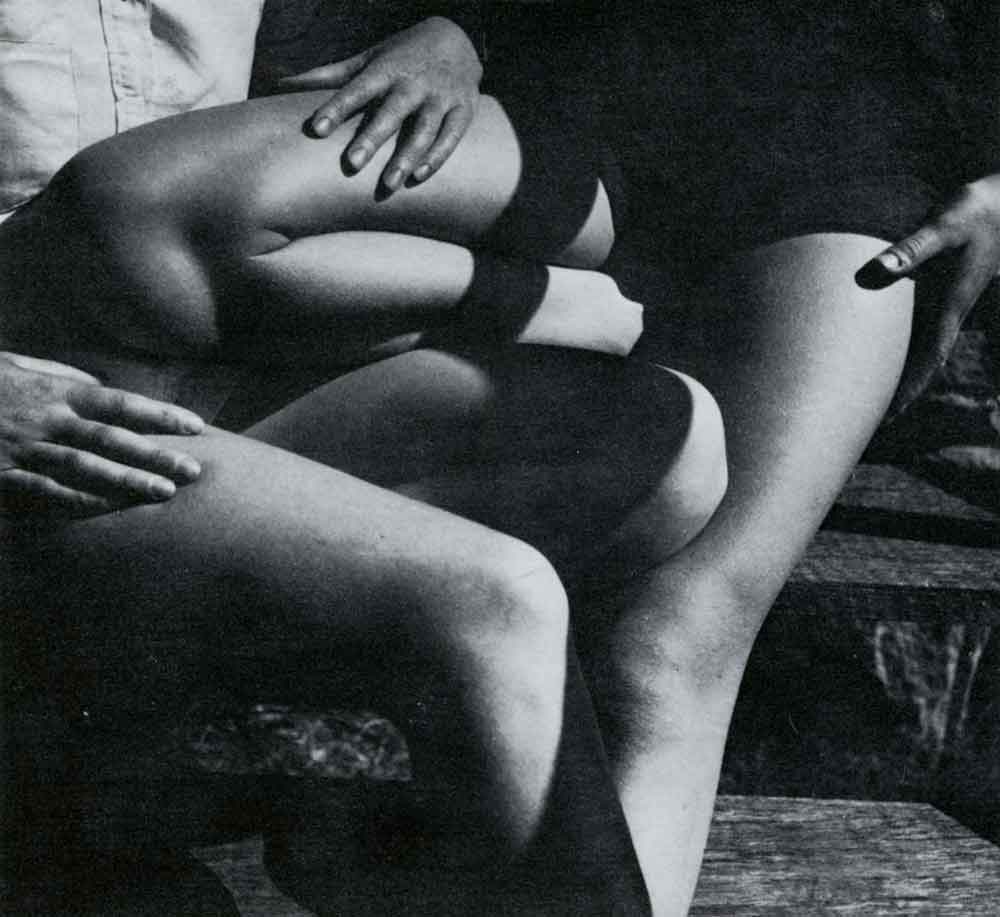

The classic 'Sunbaker' of 1937 is not about bronzed Australian surfers. It is the reduction of an object to an essential shape — struck by a particular light — in an independent spatial world. The figure • studies are a special case, inspired by a rich variety of sources; Brandt, Das Lichtbild and, one would have thought, Edward Weston.

The remarkable 'Floater' of 1939, included in the Australian Centre for Photography's retrospective show in 1976, recalls Weston's superb nude half floating in a pool (1939). Questioned on this, Max Dupain pointed out that he was not aware of Weston's work until the late forties and still doesn't own a book on his work, though he added: ''But his unforgettable images stand stark in my mind, and I realize that if they are going to be surpassed it will have to be done in a non Weston way.' 1

A crucial intellectual connection can be drawn between the work of Weston and Dupain. Dupain had read D. H. Lawrence's essay on Cezanne; there, the poet spoke of the 'appleness of apples' in one painting. Lawrence had been associated with the Imagist poets, led by Ezra Pound, in 1914 in a reaction against the excesses of Victorian sentimentality and verbal orientation. The Imagists stood for precise poetic language; they saw the artistic value of modern life 2; they described things bluntly without similes, going to the essence of the subject. Avoiding a mere catalogue of physical properties, they allowed the use of metaphor if it increased the effectiveness of the image being created of the subject. |

|

|

| |

(top) Edward Weston, Nude Floating, 1939

(bottom) Max Dupauin, Floater, 1939 |

Edward Weston came in contact with imagist ideas, and Lawrence personally, through other Americans associated with the movement; William Carlos Williams, Carl Sandburg, Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand. The value of metaphor was recognized by imagists, and it is this area that Weston developed. His wife, Charis Wilson, warns against being misled by the precision of Weston's images. In speaking of 'Nude Floating', she points to the deeply romantic nature of his vision, concerned as it was with interfaces of life and death 3.

Dupain has been a long time admirer of Lawrence's sensitivity and instinctive approach. However, where Lawrence was very much opposed to the machine, Dupain believed that he could be as sensitive but 'bend the machine to suit my own reflective terms' 4. Where Weston develops the metaphorical potential of his subjects, Dupain prefers a more abstract understanding.

He speaks of subject matter as requiring disciplined handling, any romantic indulgence resulting in obscuring of the meaning:

'/ want to extract every ounce of content from any form. I want a full range of tonality, especially from the blacks, and I want to give life to the inanimate. It's a sort of extension of my penchant for still life in the old days, e.g. 'Two Forms'. . . ' 5.

It is a refreshing reminder to us prig art historians that artists, like scientists, move simultaneously toward the discoveries their societies require. Many and varied intellectual links exist within a given period.

By 1938 Max Dupain had become a clear leader and champion of progressive photography in Australia. In a series of letters to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald in early April, 1938, on the subject of the International Photography Salon Exhibition, the divided state of photographic aesthetics between pictorialists and progressives is evident. The exhibition was one of the usual type of salon, sponsored by the pictorialists.

Harold Cazneaux, as the leading figure of the older generation, was judge and selector. In the cosy self congratulation which is still evident in current 'Sydney International' exhibitions, the sponsors claimed to show the best contemporary work from overseas available. |

|

|

| |

|

Max Dupain, Two Girls, 1935 |

Dupain was stung to reply:

'Great Art has always been contemporary in spirit. Today we feel the surge along aesthetic lines, the social economic order impinging itself on art, the repudiation of the truth to nature criterion, and the galvanizing of art and technology. Our little collection from Europe, if it was truly representative, would reflect these elements of modern adventure and research, but it is not; it is a flaccid thing, a gentle narcotic, something to soothe our tired nerves after a weary day at the office.' 6

Needless to say, the old guard rallied in defence and declared that the exhibition did have a category for 'Modern', but that it was only a minority group after all. Modernism, they claimed, was in general a fad which, at its best, was not true to art principles and, at its worst, capable of leading society to an early anarchic doom.

Even Cazneaux, who was not the amateur hobbyist that so many pictorialists were, remarked:

'Exploration along abstract lines is uncertain and the ultimate destination unknown.' 7

revealing, more clearly than anywhere else, his and pictorialism's limits.

Between 1943-45 Max Dupain served in R.A.A.F. camouflage unit in New Guinea and Australia. On his return to commercial work, Dupain turned away from the fashion and advertising work of the pre-war years.

Finding it effete after the experience of war, he now favoured architectural and industrial assignments. Images such as 'Souvenir of Bungan Beach', 1940, 'Backyard at Foster', 1940 and 'Hotel Beds Atherton', 1942 had already marked a new formal direction toward abstraction and pure geometry, with a cooler austerity than his previous more dramatic handling of form. The experiments and technical displays of the era of the surrealistic double imagery, which had declined, seemed equally superficial and fussy after 1945.

During the war Dupain renewed a friendship with Damien Parer, who had once worked in the Bond Street Studio as a still photographer, although chiefly involved with documentary film making. The war provided him with the opportunity to make the kind of tough, ironic and penetrating films that he had aspired to, encouraged by the work and writing of John Grierson.

Parer introduced Max Dupain to the work and ideas of Robert Flaherty, Grierson and the British documentary films of the Empire Marketing Board and the National Film Board of Canada. The mood and objectives of Grierson and his colleagues provided the philosophic framework for a post war world. The best introduction to the work of Grierson is through a book of selected writings called 'Grierson on Documentary' edited by Forsyth Hardy and published by Collins in 1946, which Dupain read in 1947.

Grierson was originally a social studies student of popular media and mass communications, who saw film as an educational tool perfectly suited to the needs of a complex and fast changing world. Through film it would be possible to dramatize the issues and character of a corporate machine age, in order that bewildered citizens might understand their role in it and the moral dilemmas raised by the new economics. Grierson was very much against 'art for art's sake' attitudes, and loathed the superficial and unrealistic make-believe of popular art forms, particularly commercial cinema, which he felt was always degraded by the profit motive. His acute awareness of the needs of working class ordinary people reflected his interest in the socialist tradition in the Unhed Kingdom and the impact of the growth of communism.

The Russian propaganda films of Eisenstein and Pudovkin provided him with models, but even these he felt to be too concerned with style: ''The conscious pursuit of art carries with it, in times of public difficulty, a certain shallowness of outlook. The surface values are not appreciated in relation to the material they serve, for there is avoidance of the central issues involved in the material? 8

Yet Grierson defined documentary (a term he may have originated) as 'the creative treatment of actuality', believing that poetry could be found in machines and contemporary life.

In 1947 Sydney Ure Smith published a monograph titled 'Max Dupain's Photographs'. In the introduction Hal Missingham speaks of Dupain's concepts. In Dupain's own notes he quotes from Grierson extensively: ' They believe that beauty will come in good time to inhabit the statement which is honest and lucid and deeply felt and which fulfills the honest ends of citizenship. They are sensible enough to conceive of art as the by-product (the overtone) of a job of work done. The opposite attempt to capture the by-product first — the selfconscious pursuit of beauty, the pursuit of art for art's sake to the exclusion of jobs of work and other pedestrian beginnings — were always a reflection of selfish wealth, selfish leisure and aesthetic decadence.' (of his colleagues) 9.

Later in the text, Dupain's own words show the degree of correspondence in thought:

'Modern photography must do more than entertain, it must incite thought and, by its clear statements of actuality, cultivate a sympathetic understanding of men and women and the life they create and live.' 10.

A further article for 'Australian Photography 1947' edited by Oswald Ziegler, titled 'Factual Photography', notes that 'creative treatment of actuality' infers not montage or darkroom tricks, but penetration to the essentials of the subject and the photographed re-enactment of well observed facets of life.' 11. Dupain's article was followed, and probably negated by an account of Pictorial Landscape Photography by Harold Cazneaux, by then nearly seventy. The article was meant to be provocative, but Dupain recalls that there was no response at all, which must have led him to abandon the public arena for the solitary pilgrim's path. The 'criterion of natural phenomena' rejected in 1938 had been restored, but it would be a mistake to speak of Max Dupain as a documenter in any but the more abstract senses that Grierson described.

Despite the kinship of ideas between the two men, a certain gap between Dupain's words and pictures exists for me. The essentials which Dupain seeks are beyond actualities and are spiritually linked to the kind of symbolic geometry of the eastern cultures, wherein simple lines reverberate with infinitely extended meanings.

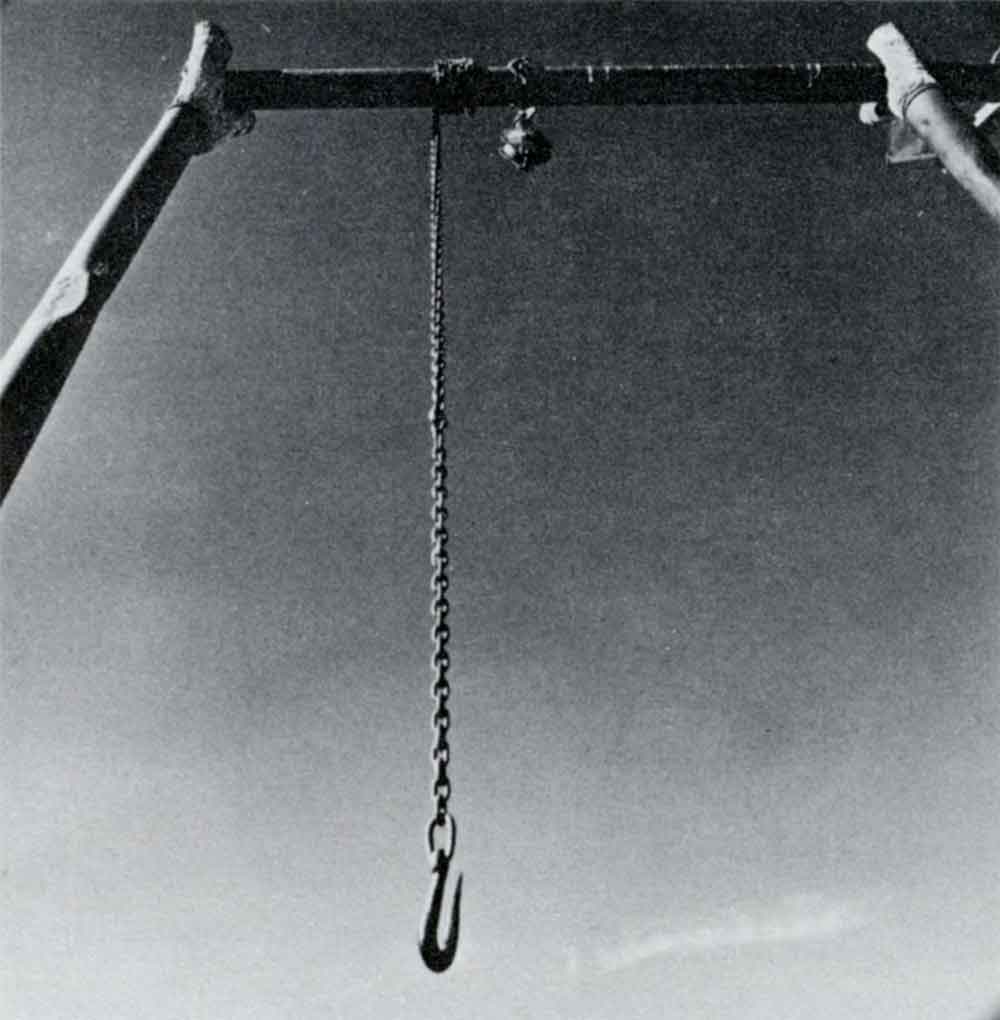

It seems that from pictures like 'Planks and Joinery' 1975 to the 'Stockyard series' of 1977, that ostensible subject matter has been dispensed with by closing in on objects. One of the 'Stockyard series', where posts appear like a guillotine, seems more austere than anything he has done previously.

From the dramatizing architectural forms, particularly those of Harry Seidler, with whom he has had a twenty five year association, Dupain has possibly abstracted the pure formal relations which twentieth century architects have sought. |

|

|

| |

|

Max Dupain, Stockyard Series, 1977 |

By temperament and training it is easy to see why self discipline and reduction to simple essentials are key words used by Max Dupain in his own comments. In the philosophy of Grierson and the realist documentary film makers he found a suitable intellectual framework.

Much contemporary work strikes Dupain as subjective and selfishly indulgent in all the ways that Grierson criticized. His concern over verbalizing about photographs reflects a deep suspicion that talk about photographic aesthetics prevents the catharsis of working through some impersonal external piece of actuality. actuality.

In May this year Max Dupain will travel overseas for the first time, to photograph Harry Seidler's new embassy in Paris. It has been almost an act of faith in Australia, and a self restraint, not to have tasted the pictorial paradise before. The problem of the dilemmas of creative artists in Australia to which he refers is too complex to go into here, but there is a vast literature on the subject.

As a major Australian photographer, it is important for Australians to confront Max Dupain's work. My personal act of doing so is too fresh to attempt to try to relate his achievement to an international situation.

Footnotes

- From a letter to the author, March 23rd 1978.

- For a short account of imagistic theory see Tmagist Poetry', Penguin 1972 — ed. Peter James.

- Ben Maddow, 'Edward Weston; Fifty Years'. Aperture 1973, New York. Plate No. 241.

- Letter to the author, March 231978.

- Letter to the author, March 23rd 1978.

- Sydney Morning Herald, March 30th 1938.

- Sydney Morning Herald, April 8th 1938.

- 'Grierson on Documentary', Forsyth Hardy. P 119.

- 'Max Dupain Photographs', Sydney Ure Smith, 1947. P 10.

- 'Max Dupain Photographs', Sydney Ure Smith, 1947. P 12

- 'Australian Photography', 1947 — ed Oswald Ziegler. P 11.

* Light Vision was a quality photography magazine published in Melbourne - editor Jean Mark Pechoux

there were eight issues during 1977-1978

click here for accompanying essay by Max Dupain - published alongside the above in Light VISION #5

Gael Newton

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|