In Search of the Native:

Photographs by Max Dupain and Eduardo Masferre and their contemporaries

Brochure originally published for the 2001 NGA exhibition

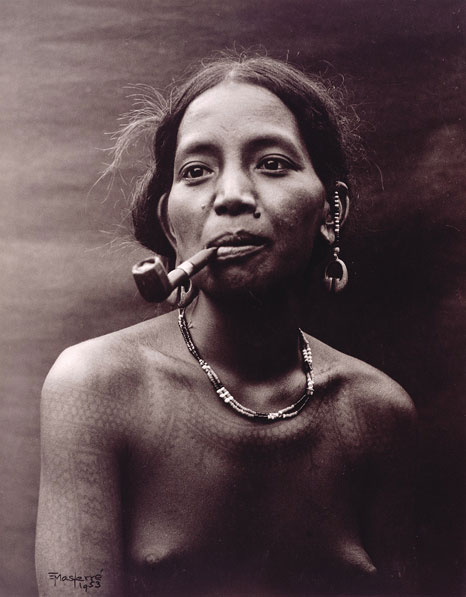

Eduardo Masferre, Woman with her pipe. Butbut, Tinglayan, Kalinga 1953 gelatin silver photograph

Introduction

In Search of the Native: Photographs by Max Dupain and Eduardo Masferre and their contemporaries focuses on two special acquisitions made by the National Gallery in 2000. The first is the New Guinea series, a unique portfolio of twenty-seven photographs taken hy Australian photographer Max Dupain (1911-1992) during his war service. It is the only known group of exhibition prints in a portfolio made by Dupain before 1980.

The New Guinea series was originally acquired by William H. Quasha while he was in Australia with the US Army during World War II. Quasha sat for Dupain in 1944 and presumably acquired the New Guinea portfolio at that time. The portfolio was first offered to the National Gallery in 1992, but it was not until 1999 that the purchase was completed. The prints are marked with an edition no. 1/12, though no other edition is known. Each is signed, titled, and dated '44' in pencil, though Dupain appears to have been in New Guinea only in early to mid-1943. He may have dated the portfolio by its production year. New Guinea pictures are dated 1943 in his later publications.

The second acquisition featured in this exhibition is equally rare. It is a group of thirty-three vintage exhibition prints (some hand-coloured) taken between 1935 and 1954 by Philippine photographer Eduardo Masferre (1909-1995). The Southeast Asian art dealer Thomas Murray of California acquired the prints in 1981 from Masferre, when his work was not so highly valued. Exhibition prints by Masferre are very rare, as he did not often show or sell his work in this format in either commercial or public galleries. Most of his work was distributed in postcard format. This is the National Gallery's first acquisition of a large group of works by a senior 20th-century photographer from Southeast Asia, part of a commitment to increasing the representation of Asian photographers and photographs of Asia in the national collection.

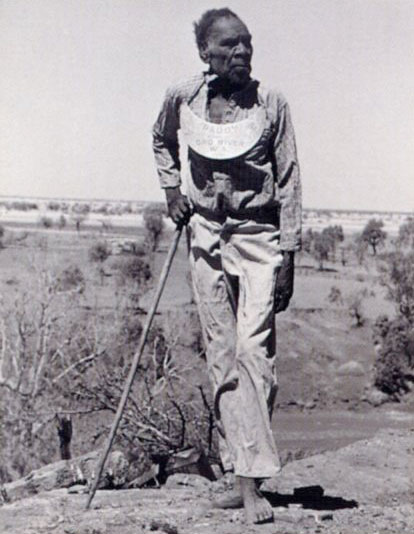

Axel Poignant, Paddy, king of Ord River 1947 gelatin silver photograph

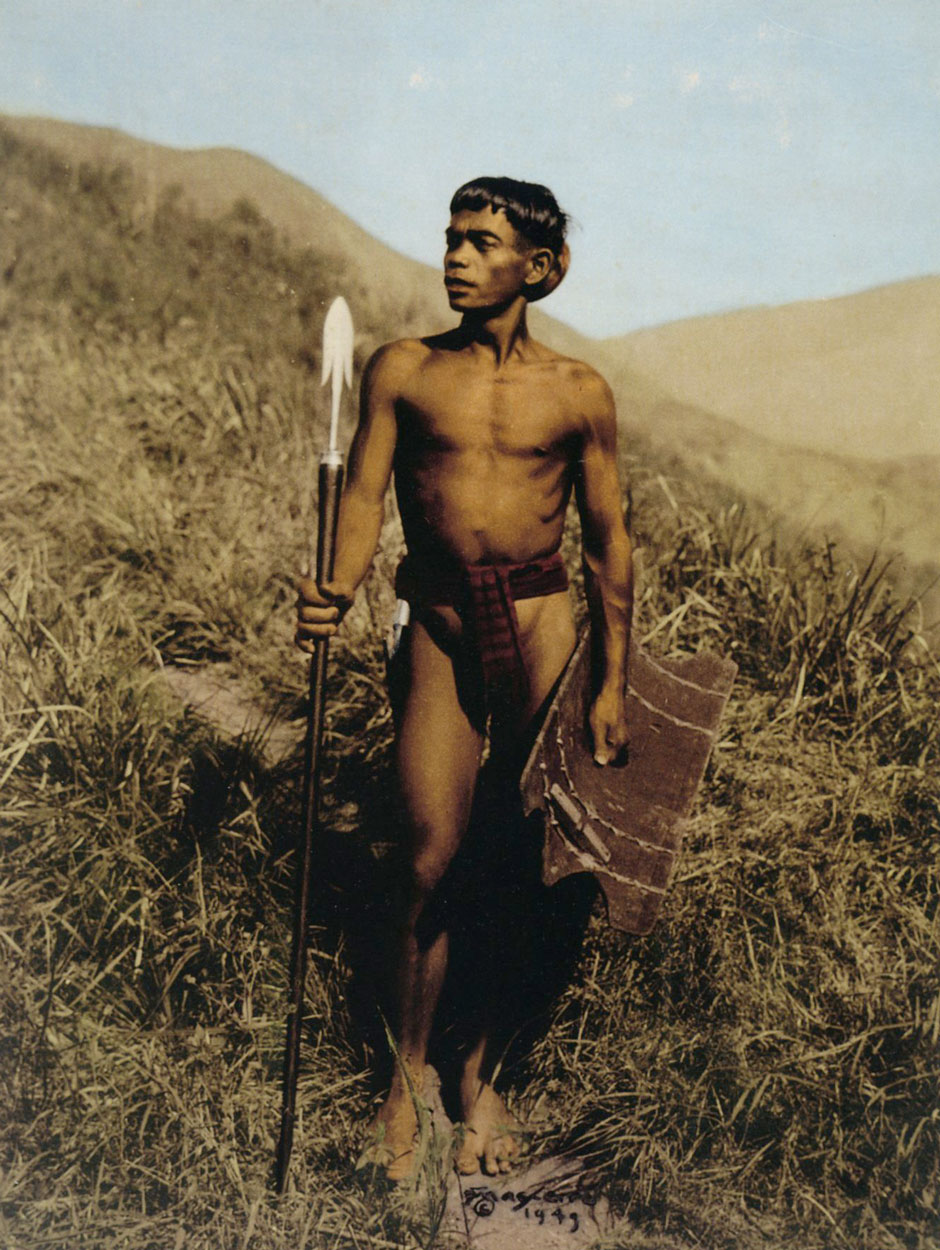

Eduardo Masferre, Man on the way to check his rice fields, armed with spear and shield. Ngibat, Tinglayan, Kalinga 1949

gelatin silver photograph, colour pigment

Eduardo Masferre, At the papatayan [sacred grove]. Malegkong, Bonto/c, Mountain Province 1949 gelatin silver photograph printed 1950

'The sympathy between Masferre and Dupain's exhibition prints is most noticeable'

In Search of the Native

When these works were brought together in the process of acquisition in 2000, conjunctions in approach could he seen in Masferre's and Dupain's portraits of indigenous people in which the subjects appear relaxed and normal. Stylistic features common to modernist photography of the 1920s to the 1950s can also be seen in both photographers' mix of spontaneity and formal design in their compositions, in their use of close-ups and views of figures seen from below or silhouetted against the sky. The point at which their work converges is a shared interest in the documentary photography and photojournalism celebrated in Edward Steichen's Family of Man exhibition in 1955.

The mammoth 1955 exhibition Family of Man, mounted by Edward Steichen, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, exemplified the humanist genre of documentary-art photography. Family of Man toured the world in the 1950s, reaching Australia in 1959. It was a controversial exhibition; many critics felt that its search for universal brotherhood ignored the cultural differences between peoples and the capitalist west's political exploitation and destruction of the cultures of less industrialised nations. Neither Masferre or Dupain were represented in Family of Man, but several Australasian photographers were, including Laurence Le Guay, whose photograph of a New Guinea Kanama ceremony also appears in this exhibition.

Although separated geographically and culturally and following very different careers as photographers, Dupain and Masferre were contemporaries. Their lives had some important similarities. Both men travelled very little outside their homelands. They made use of books and magazines from abroad for technical and aesthetic guidance and were part of broad trends in modern photography from the 1930s to the 1950s. Masferre and Dupain are both revered as key figures in the history of photography in their own countries, yet remain virtually unknown internationally.

The sympathy between Masferre and Dupain's exhibition prints is most noticeable. They are the warm-toned, matt-surfaced exhibition prints in fashion between the 1930s and 1950s, which gave a softer character than the ultra-sharp cold-toned glossy prints used in reproductions or by more avant garde modernist photographers. Dupain would not have approved of the hand-colouring which Masferre used extensively during the early 1950s.

Dupain regarded any heightening of the inherent character of black and white prints as too close to the manipulations of the Pictorialist photographers, who idealised their subjects and favoured sentimental titles and 'story' elements. Masferre worked under much greater restrictions of equipment and supplies than Dupain. Masferre used solar enlarging to print his work until 1946, when he acquired an electric generator and enlarger.

Masferre lived a relatively quiet life. He rarely exhibited in an art photography context and his work has largely been used in anthropological publications. His vision was not scientific and impersonal, he wished to preserve a vivid portrait and a sense of the vitality of his subjects, as well as recording customs and costume of the Cordillera people.

In contrast, Dupain worked all his life in Sydney as a commercial photographer in a broad range of fashion, advertising, social portraiture and personal documentary work. He pursued a career as an exhibiting artist-photographer. Dupain is part of a European modernist tradition of art photography with an emphasis on personal interpretation and formalism even in his documentary work.

Masferre's father was a soldier in the Spanish colonial army. He remained in the Philippines after the islands were ceded to the United States by Spain in 1898. He settled in Sagada, in the Gran Cordillera of Luzon and married a Kankana-ey woman from the Sagada region. Eduardo Masferre had his early education in Spain, returning to the Philippines at thirteen. Although the family had little contact with the Kankana-ey villages and rituals, Masferre learnt to respect the beliefs of his mother's people, though these were often dismissed as pagan superstitions.

Masferre's vision was not scientific and impersonal, he wished to preserve a vivid portrait and a sense of the vitality of his subjects

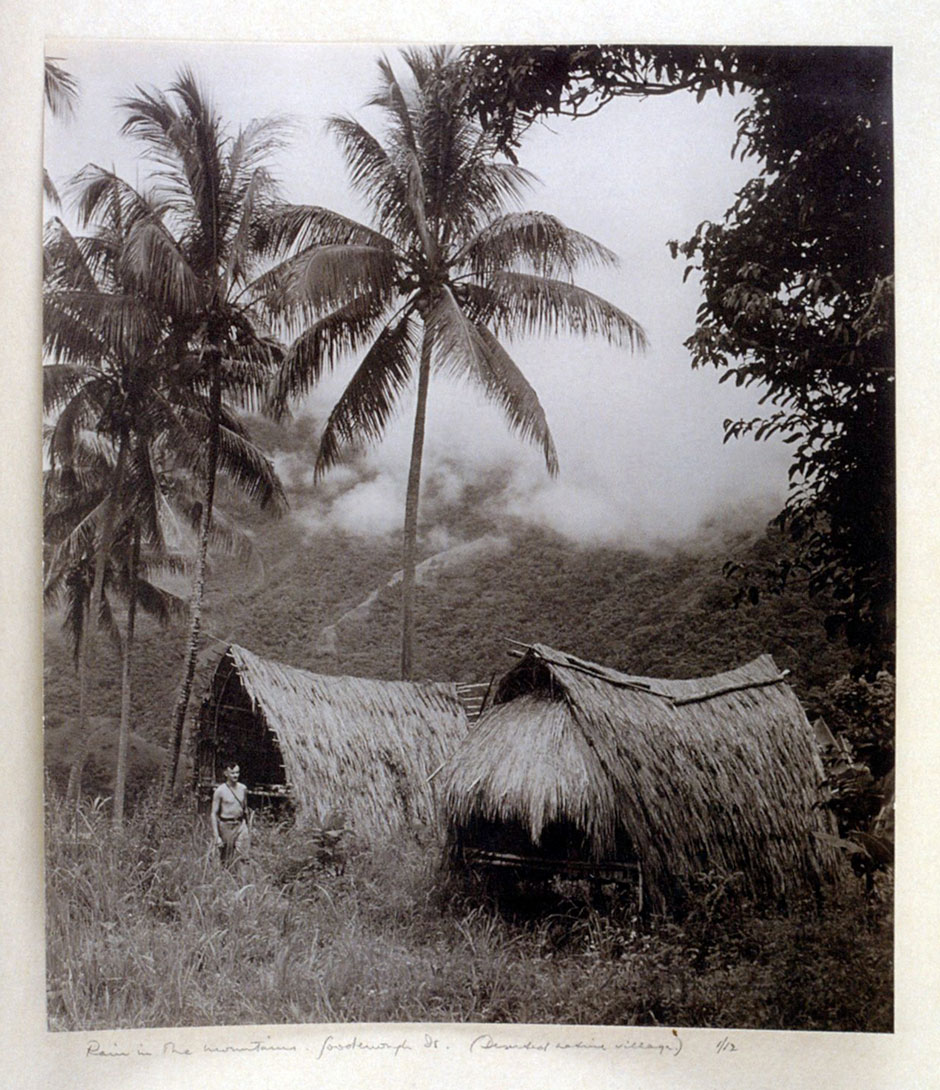

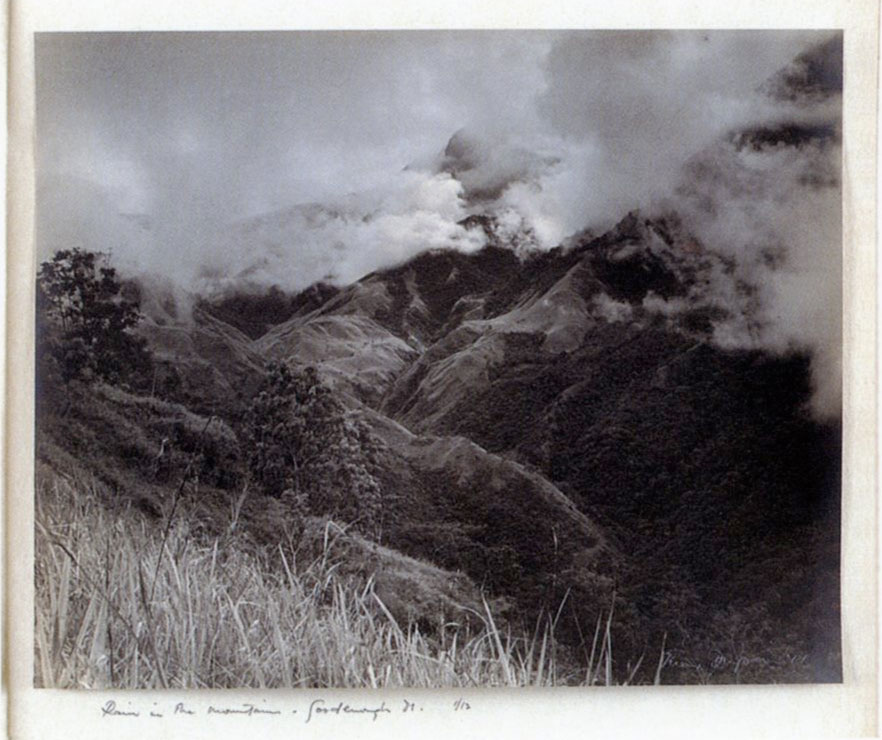

Max Dupain, Rain in the mountains - Goodenough Island [deserted native village] 1944 from New Guinea series gelatin silver photograph NGA Photography Fund (Dr Peter Farrell donation)

Max Dupain, Rain in the mountains - Goodenough Island 1944 from New Guinea series gelatin silver photograph NGA Photography Fund (Dr Peter Farrell donation)

Masferre's first experience with photography was at fifteen. One of the priests took black and white photographs of the Mission school in Sagada which Masferre helped to print. Masferre devoured American magazines: Colliers, the Saturday Evening Post and National Geographic. The articles and ethnographic photography of the Cordillera peoples by Dean C. Worcester (originally published in 1911-1913) remained most vividly in his memory. In 1934, while working as a teacher in a local primary school, Masferre sent to Manila for a box camera, some film and a kit for processing. With little outside help or influence he taught himself photography and chose as his subject one that was not popular but which he considered important - the native peoples and their way of life before it was transformed by modernisation.

He saw photography as 'a way to document the life here as it is, because it is a different life from life elsewhere'1. From 1934 until 1956, when he took up farming to support his family, his photographic work was an elected vocation born of spiritual and cultural concerns as much as any conventional ethnographic documentary project. The Bontok, Kankana-ey, Kalinga, Gaddang and Ifugao of the Cordillera were among the few pre-Hispanic cultural groups to resist and, in the main, evade Spanish influence and governance.

Masferre captured the life that these people had carried on for centuries. Being half Kankana-ey, Masferre achieved a rapport with his subjects, gaining their co-operation and trust. But he was detached enough from the native people to distinguish as meaningful the sights they thought commonplace. In his most productive period, between 1934 and 1956, Masferre produced around one thousand negatives and many prints. After World War II, he moved from Sagada to Bontok and opened a studio there, doing mostly portrait work, later marketing postcards of the region. He continued his personal work on the Cordillera people when he could, but it was not meant to be a profitable venture.

With little outside help or influence Masferre taught himself photography

Eduardo Masferre, Harrowing a field accessible to a carabao [water buffalo]. Sagada, Mountain Province 1938 gelatin silver photograph printed 1948

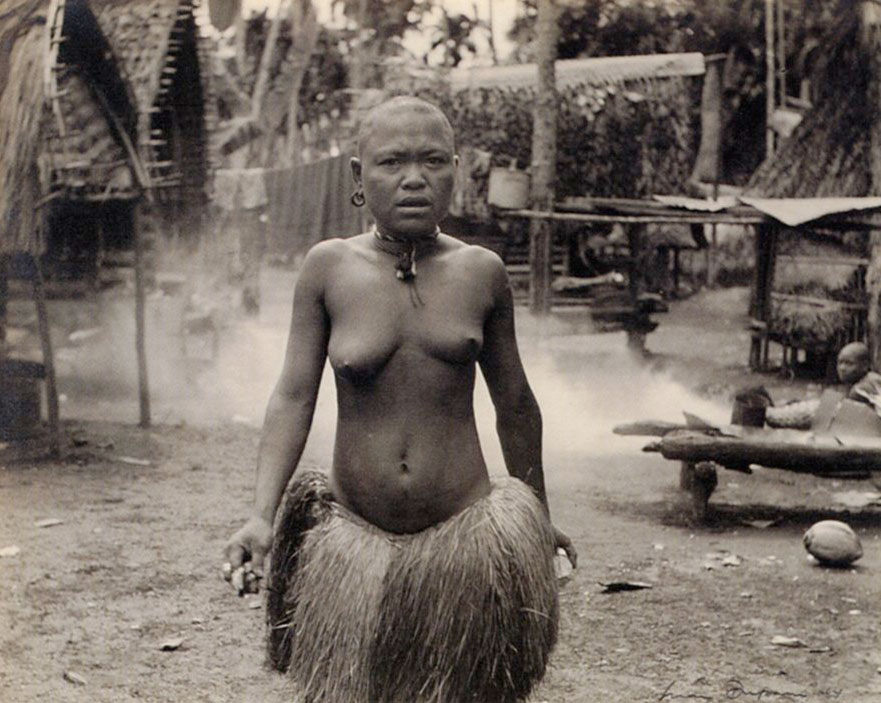

Max Dupain, Native woman - Trobriand Islands 1944, from New Guinea series, gelatin silver photograph, NGA Photography Fund (Dr Peter Farrell donation)

Recognition of Eduardo Masferre's work came late in his life. During the Decade of Philippine Nationalism, which culminated in the centenary of the 1898 independent Philippine Constitution, the first peoples of the Philippines were seen in a new light and Masferre's work became a national treasure. Masferre recalls that in the 1950s, many Filipinos thought his pictures should not be exhibited because the subjects were primitive: 'Now, I hope they will look at my pictures and say "this should be kept'".2

Interestingly, the work of Max Dupain was also rediscovered in the same period. Similar nationalist enthusiasm, created by the Australian Bicentenary in 1988, fuelled a search for national identity, and Dupain's images were recognised as a quintessential expression of part of his country's culture.

Unlike Masferre, Dupain did not take any particular interest in Australian's indigenous people. Masferre's work can be better compared in this context to that of the Anglo-Swedish photographer Axel Poignant (1906-1986) who immigrated to Australia in 1926. Poignant was interested in Aboriginal culture from the earliest period of his residence and, like Masferre, his work was unofficial and personal. In 1952, he worked in the Aboriginal communities of the Liverpool River region of the Northern Territory which, like the Cordillera, was changing under outside influences.

Dupain's New Guinea images are probably not the result of a personal commitment to documenting Papuan village life. Dupain was in New Guinea because, in 1942, he had joined the newly formed Camouflage Unit. The unit was established to create the camouflage schemes needed in tropical warfare. A number of other Australian artists joined, including William Dohell, Robert Emerson Curtis and Clem Seale. In 1943, Dupain was sent to New Guinea for four months. The Camouflage Unit headquarters was on Goodenough Island. Dupain worked with the Royal Australian Air Force and the American forces there and at Tami Island, Finschafen and Port Moresby, taking photographs wherever he went.

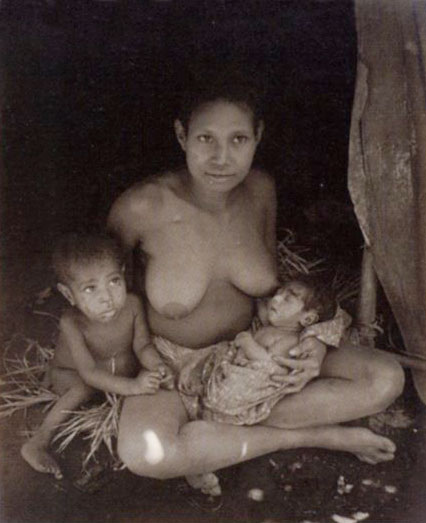

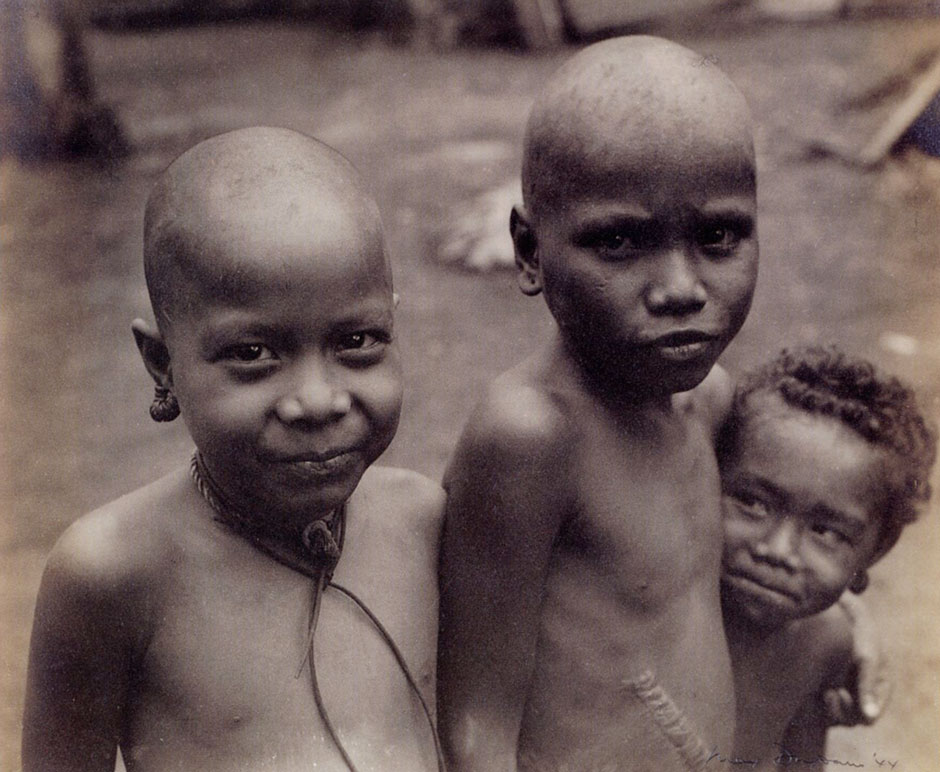

Dupain was never an official war photographer, unlike his close friend Damien Parer, who was killed in action in Peleliu in September 1944- Dupain's New Guinea images were made for personal reasons, perhaps as a consequence of finding himself away from his homeland for the first time. The subjects are chiefly Papuans in their villages but Dupain's purpose was not anthropological and the subjects usually look relaxed in front of the camera.

The portfolio includes some atmospheric landscapes and several scenes of Australian soldiers and military camps. The mood is quiet, even sombre, and the evidence of the war sits lightly in the midst of an idyllic, isolated locale. His subjects are not spied upon or exhibited as sensational and exotic. Dupain's New Guinea is about the daily rhythm of village life, in contrast to the images of earlier photographers, which dwelt on the sensational or exotic aspects of native people.

Max Dupain, Native mother and children — Nadzah 1944 from New Guinea series, gelatin silver photograph, NGA Photography Fund (Dr Peter Farrell donation)

Max Dupain, Native boys - Trohriand Islands 1944, from New Guinea series, gelatin silver photograph, NGA Photography Fund (Dr Peter Farrell donation)

The National Gallery of Australia is proud to bring the work of Masferre and Dupain together here. The images express the broad current of thinking and taste which identified the traditional ways of non-industrialised indigenous peoples with the social, communal and cultural values lost in western culture.

Other photographers who, at some point in their careers, had a special interest in representing indigenous peoples are also shown in the exhibition. Photographers at work in Asia, Australia and Mexico between the 1920s and 1950s have been included. In concert with their contemporaries, Max Dupain and Eduardo Masferre each added individual and regional perspectives to the search for the authentic in the worlds of pre-industrial peoples.

Notes

Jill Gale de Villa, Maria Teresa Garcia Farr and Gladys Montgomery Jones, Eduardo Masferre, People of the Philippine Cordillera Photographs 1934-1956, Devcon I P Inc, 1988, supported by Mobil, p.7

Jill Gale de Villa, Maria Teresa Garcia Farr and Gladys Montgomery Jones, Eduardo Mas/erre, People of the Philippine Cordillera Photographs 1934-1956, Devcon I P Inc, 1988, supported hy Mobil, p.10

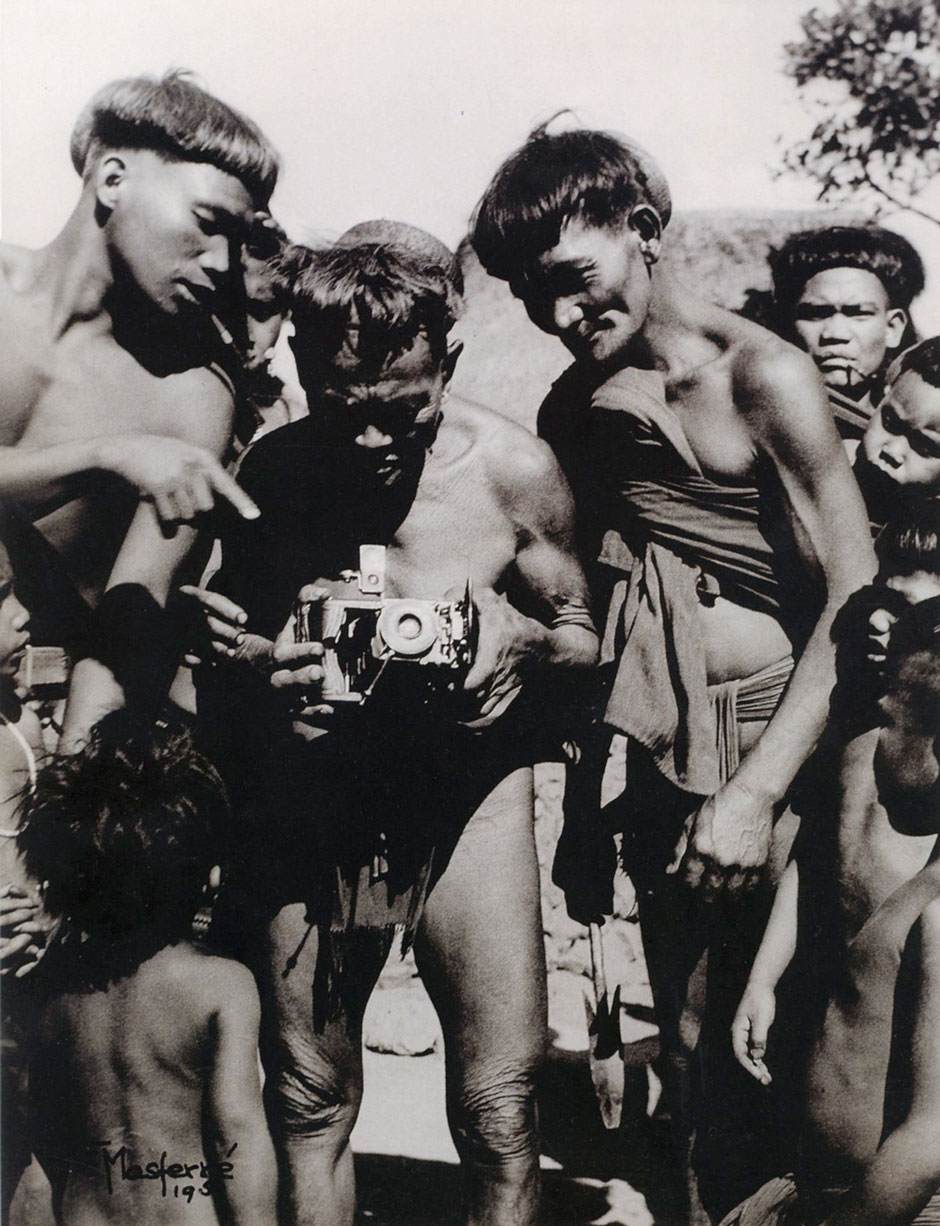

Eduardo Masferre, Investigating a camera. Butbut, Tinglayan, Kalinga 1948 gelatin silver photograph prinred 1950 Narional Gallery of Australia

The exhibition was curated by Gael Newton, (then) Senior Curator of Photography

and Anne O'Hehir, (then) Assistant Curator of Photography.

more Essays and Articles

|