Irreverence:

a gloss on the photograph and the smile

originally published by the Australian Centre for Photography,

Photofile 55, November 1988, issue: Happy Snap |

|

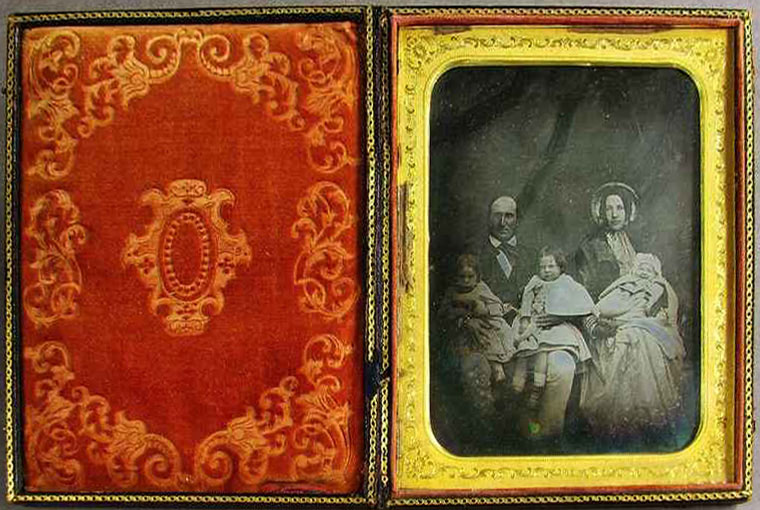

Sometime in the mid 1850s John and Rebecca Ross and their three daughters — from left to right, Sarah, Rebecca and baby Henrietta — sat for a family portrait photograph, probably in an Adelaide studio. They are dressed in their best and indeed rather abundant clothes, suggesting it was perhaps chilly under the blue glass roof in the studio.

Unknown photographer South Australia

John and Rebecca Ross and Family c1855 - half plate daguerreotype

Mortlock Library State Library of South Australia B16095

Their image is on the expensive half-plate size of daguerreotype but the execution and composition are primitive. The Ross family sitting was an antipodean performance of what was, by then, a world-wide domestic ritual of the upper- and middle-class trade in photographic likenesses. The family was still within the first middle-class generation to have self images as an option.

The Ross family portrait attests to stability and prosperity in a new land, and the affluence of the clothing belies the physical hardness of John's working lite and long overland journeys. In the mid 1850s, however, his repute as an explorer was still in front of him — in the 1870s. We know about the Ross family because of the intersection of John Ross's public and private roles.

The family portrait is now a useful historical document but what is unforgettable about this image is baby Henrietta's spontaneous grin, a virtual fluke of animation for daguerreotypy. Her gummy display is a sideshow, even a Barthesian punctum, which steals the show from her glum sisters and sober parents. What the baby saw in this daguerreotype was the funny side. Unschooled in reverence for camera ritual the baby finds the photographer a joke — or was it just wind?

The long exposures of portrait photography in the first decades of photography meant that self-presentation for the camera was a sober affair. Babies and children were frequently shown asleep, or pinioned by parents. If awake, their poses show awkward discomfit and their faces anxiety and distrust. Photography freezes time but it also has one foot in the grave. Lacking images of their loved ones in an age of high mortality, posthumous portraits were also part of the photographic repertoire.

Writing over a century later in 1959 and from the social values of the post war era, the Australian poet John Thompson expresses commonplace sentiments about the cadaverous nature of photography. He is disturbed by the emotionless visages of early portrait photographs which paradoxically render their subjects in prfound unlikeness:

What of this statuesque unbending wife?

This frigid frowning father? None will guess

That she was sprightly and lovable all her life,

And he had a name for fervor and friendliness

The ubiquitous camera dictums of saying 'cheese' and smiling for the camera was a conditioned response still decades away in the snapshot era. This response would barely be seen until the era of the snapshot in the 1890s. Indeed the energetic smiling face is perhaps most associated with the late 1920s and early 1930s when the new 35mm camera was recruited to the cause of portraying in pseudo-spontaneity all those healthy proletarian boys and girls striding into the future, an association which has perhaps accounted for the banishment of the smiling photo from the museum of photography.

When the author became a mother in 1982 my relationship with photography changed. I seized the fat envelopes of baby snaps from the chemist like a penitent, quite regardless of my sophisticated photographic education (son number one was much more photographed than son number two).

Photography became the great leveller and I shared the delight Mrs Ross must have felt in her babies' images, ignorant of any sadness which might he in the future. Her joy was short lived. Mrs Rebecca Ross died in 1869 after having two more children. In my case the marriage died and the child as teenager pulls away.

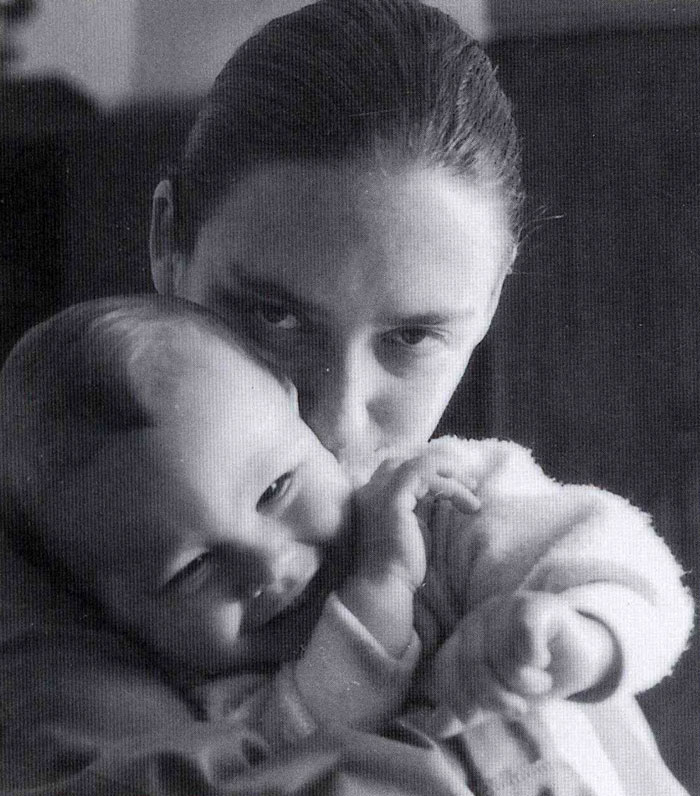

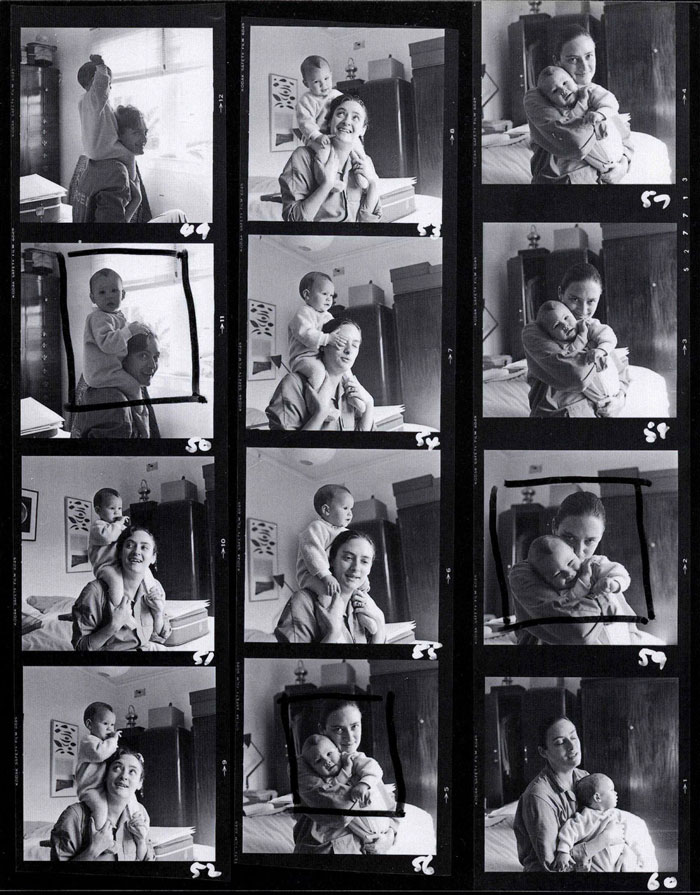

My vocation as a curator and friendship with Max Dupain led to his offer to photograph me and my first born, a rare portrait excursion for him. He arrived early and found me unshowered and in overalls and the baby in daggy bunny suit. No matter, the shoot was short and efficient. I despaired of the result, especially when the contact sheet was delivered with a single image marked up for development. Dupain made an exhibition print of this frame in which the ordinary weekend morning and seemingly spontaneous moment between mother and child became mysterious and slightly exotic.

As an art print, the work was no longer 'ours'.

Two photographs of smiling babies, taken with radically different technology and aesthetics but both representing happiness in their families. They also stand for the intertextuality of documentary and for the historical, visual and aesthetic aspects of photography. Asked to write on a few funny or happy photographs, I did not expect to find many in the art museum nor even the library archive, nor the vast literature and histories of photography. Things which the medium does so distinctively in the arena of motion and emotion, especially the smiling faces of commonplace family photographs, are few. This arena is left at best to the picture magazine.

The photoart archive seems to be much governed by an idea that to be a serious art form photography is expressed best by literally serious subjects and controlled colouration. Trawling for poems in anthologies it also seems that photography is little celebrated. But it is also seemingly the case that fear of the represented image exists well beyond the precepts of Judaism and deep anxiety recorded so often in early portraits of children underlies the medium's history and interpretation. On the way to the millennium, sadly, photographic art is far from being funny.

Gael Newton

more Essays and Articles

|