FIONA HALL

RETRO-SPECT LEURA'S THEME

originally published 1997 as a paper within A Small History of Photography

It was a case of love at first sight in 1974 when I saw Fiona Hall's photograph Leura in her final year presentation in the old cell block of East Sydney Tech. I still love it but perhaps now I can say a little more about why- and about its relation to later developments in her work as an artist.1

It was of course not a naive encounter. Having myself only graduated from an art school two years before, we shared common ground in photographic education ants formalist aesthetics. At that time I would not have imagined the directions in which photographic aesthetics in general, or Hall herself, would go over the next twenty years.

Photography seemed set to continue doing what advocates of a dominant purist aesthetic proclaimed it did best, recording anti exploiting its genus of romantic naturalism. The massive decampment of young photographers in the 1980s, from reportage on the world into studio tableaux and artifice, was barely imaginable in 1974.

But it is from a retrospective perch that we now see Hall's work and it is hindsight which enables a gloss upon her early images. This luxury of being able to plumb several decades of work by a contemporary woman photographer is a new experience.2

The careers of mature or past women photographers were largely invisible in the seventies and early eighties, Even with feminist retrieval projects their numbers will never match the waves of art school graduates in photography from then on, What makes revisiting Hall's first works especially interesting is that she is (me of a number of 1970s women artists in photomedia whose earlier work in documentary / feminist / social mote has, on the surface, undergone considerable evolutions in appearance, scale, subject matter and style. Their 1980s - 1990s works tend to be larger and more dramatic, staged in composition, manipulated in painstaking, hybrid in medium anti incorporate quotation from the figurative and narrative traditions of western art.3

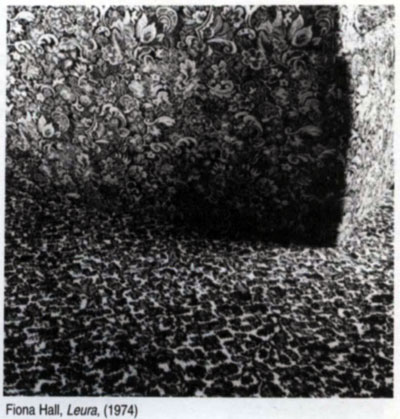

In Leura a sturdy armchair fuses with a carpet. Indeed its prow-like edge appears to part a floral sea into which it dissolves on the left. As an image it is a collusion of surface and volume.

Leura is sensuous even playful in its illusory metamorphosis but it is also a still point. Light fails from high on the right, rendering the moment the kind ' of scorner of creation' of a painting by Vermeer. Both chair and carpet are intricately flower-patterned in the manner of oil tapestries, but not identical. The pictorial confusion of figure and ground arises from the fine tonal distinctions of large format photography which Hall practised.

The image is also classic camera vision in its close-up and reductive framing. The camera's facility for scrambling tile cc-ordinates necessary for the rationalized window-view of mimetic art is one of the most utilized strategies in modernist photography. In the seventies the meaning of Leura could have been unpacked (however, close reading of images was not then popular) in terms of both the prevailing personal documentary photographic aesthetic and formalist aesthetics.

Equally influential for Hall was her passionate interest in the sensuous, fluid exchange between line and volume of the early 20th century master painter Henri Matisse. Her early works, though mostly taken outdoors, were not landscape or architectural studies as such. Nor were they the bizarre/bland 'new topographies' of contemporary American landscape photographers.

Leura could be placed within a rather peculiarly American fusion of European 'New Objectivity' with the literary theory/cum philosophy of vitalism of the 1920s, as in Edward Weston's work but elaborated by later 'mystic realists' like Minor White. Nature in Hall's images is one in which there is a subtle human intervention as in Marrakesh (1976) in which a grove of palms and cultivated trees line up in neat rows inside a walled garden.

Hall's first studies were in painting but by second year she, like many of her generation, Hall switched mediums to photography which seemed unplumbed and to have no burdensome history. She had been introduced to photography as a teenager through her brother's hobby of train spotting. Hall left Australia soon after graduation determined to stay away 'long enough to undergo change'.

She returned in 198O having done postgraduate study at the Visual Studies Workshop under Nathan Lyons in Rochester, New York State. There she discovered the intricate surreal images of the American photographer Frederick Sommer4 whose work was influenced by the writings of Paracelsus, the 16th century Swiss physician and gnostic philosopher. Later she read texts such as Frances Yates' The Art of Memory (1966)5 on the complex thought and images of Renaissance theorist Giordano Bruno and other theorists of systems of memory based on images.

By the 1980s Hall was assembling objects in complex tableaux which she then produced as photographic works in colour. These works such as Marriage of the Arnolfini after Van Eyck, went beyond an ironic post-modern fashion for quotation my their overt but uncanny reconstruction of the originals in mundane objects anal materials. A later series used a diverse assemblage of objects to construct the kinds of cosmic systems beloved of Renaissance scientist philosophers. Hall's acute awareness of formal resonances in tile 1980s' works was what Renaissance intellectuals would have delighted in as illuminating and entertaining 'conceits'.

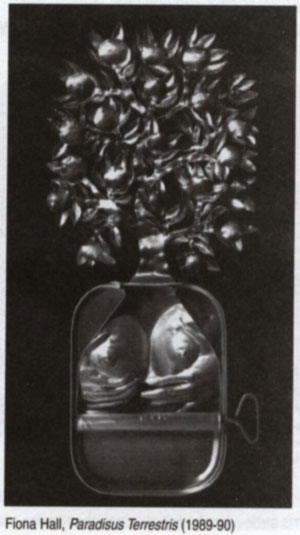

The works present the too easy potential for one thing to elide into another, to echo it or lose its own integrity in favour of another reading. Hall later proceeded to exhibit independent three dimensional works such as the extraordinarily intricate relief cut-outs of the Paradisus terrestris series in which botanical specimens and sexual organs have a bizarre concordance confirming the cosmic harmony hidden in nature beloved of the gnostic philosopher/ theologians. Since 1993 Half has increasingly worked in three-dimensional installations.

In I993 the National Gallery of Australia mounted a survey of hall's work titled The Garden of Earthly Delights, the work of Fiona Hall. The catalogue essay by the curator Kate Davidson, defined Hall's work as a dialogue between nature and culture. The title of the exhibition, with its reference to the famous series of paintings of Heaven and Hell by the 16th century Flemish artist Hieronymous Bosch, does not come from the title of any particular work by Hall, but reflects the artist's frequent use of sources from that period and her engagement with relationships between nature/culture and morality.

A later title concept which Hall thought even closer to her work was In the vicinity of Eden Davidson's catalogue essay affirms that conceptual sympathies as well as visual affinities exist between Hall's work and the great western cultural traditions. In particular the form and concept of a lost harmony between humanity and the cosmos, as in the Christian belief in the existence of an earthly paradise, is a recurrent theme.

As Davidson notes: "Much of Hall's imagery is based just outside the garden wall: it depicts the circumstance of contemporary human existence and our persistently tenuous relationship with nature. "

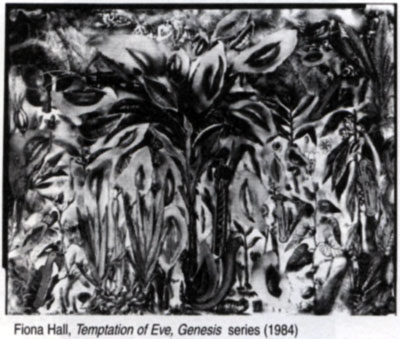

In the appropriately named Exit from Eden and Temptation of Eve from the Genesis series (both 1984, a year with its own significance in terms of depiction of a soulless world) Hall works over the book of Genesis in what was already her distinctive maelstrom of images. Eve is reduced to seductive smiling lips seemingly sprouting ant spawned from a feral plant; a neat conjunction of woman-as-nature anti evil human nature.

Fragments of medieval woodcuts showing the scourging of nude women are in the background. The fertility of women (painful childbirth being the curse and blessing of women after the Fall) their allure and power, mocks the modern pen knives hovering ready to prune and castrate generative power.

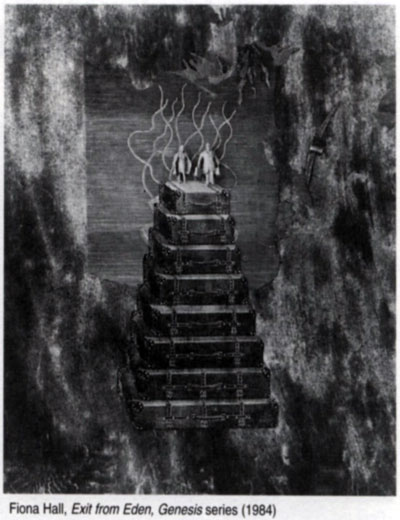

In Exit from Eden a couple jauntily set out from paradise in nineteen forties dress. Their smart suitcases are perhaps packed with their cultural baggage of stolen knowledge of the world, sex, death anti damnation. They stand upon a tower of Babel made of suitcases, from which tendrils swirl as in some sci-fi horror of mutated growth.

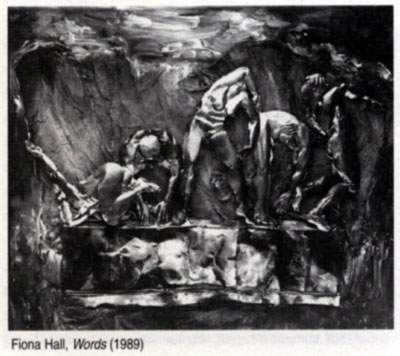

Hall's later series Fords (1989) presents a sharp twist on the interrelation of word and image and develops the Babel theme. Figures (mate by repoussé method in thin metal) contort to form letters. Words as the embodiment of worldly knowledge become the source of survival and. damnation. Language is scourge and saviour at once.

In the beginning was the Word... but human language became a travesty in the city of Babel and God punished human ambition to climb back to the heavens. The peoples of the earth were made lo speak in different tongues so they would have communication problems through their literary as well as physical differences.

Hall's 1980s works are frequently sober even dark fantasies and furies with apocalyptic overtones. Dante's Inferno provided the inspiration for one series. Her imagery reworks religious, cosmological and scientific classificatory systems from medieval and renaissance texts as well as the word/images of literary figures of tile 20th century such as T.S. Eliot, who also followed a modern allegorical art of collage and disjunctive fragmented imagery.

Hall does not combine references in the way that Eliot (a convert to Catholicism) sought to revive an iconographic language. Eliot was also drawn to the Italian writer's work and Hall's reprise, like so many later artists and writers, rather favours the depiction of hell over heaven. The references Eliot makes are more securely tied to the subject and meaning of the original models.

Hall is neither a formalist, born-again Christian fundamentalist nor a surrealist type using imagery with indifference to its original connotations. Is Hall however, a contemporary gnostic at least in her interest in the relations between the natural order and human systems of knowledge? How are we to approach the relation of the imagery to its sources?

Modernism, in rejecting old beliefs and cosmogonies, surely broke forever any real relation with the iconography of the past. We became the new lost souls in our profound unmooring. The revival of imagery from the past art in the eighties is assumed as ironic quotation not for serious analysis. So few would have the education outside the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes to decipher Hall's images in regard to their contribution/continuation of the older tradition (it would be an interesting exercise). The cosmic mirroring evidenced by nature was a tenet of the hermetic tradition, a tradition which in itself was a response to the growth of a secular science which gave literal explanations to previously ineffable mysteries.

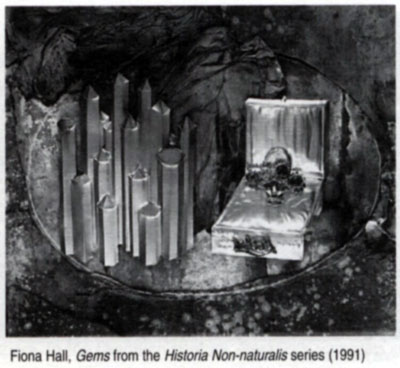

One of the most layered of Hall's images is Gems (1991 ) from the Historic Non- naturalis series in which she assembles an old fashioned jewel box and two brooches. One spells out the word 'mother' in reverse lettering. The inspiration came from Historia Nataralis by the ancient Greek philosopher Pliny the elder whose thought and writings Hall had plumbed.

In regard to Gems, Hall recalled Pliny's questioning of gem culture: 'how many hands are worn by toil so that one knuckle may shine'.

Gems are human adornment powered by technology to rival the natural splendours. Minerals were a source of constant fascination to the Renaissance systemisers. Not only did they have magical astrological properties, but they could be used to access a higher order of knowledge and ecstatic experience.

Hall's background sheds some light on her botanical and scientific interests in the garden of Eden and Nature. Her mother was a physicist (she died in 1981) anti her father a Telecom linesman. Both were radicals in politics and devoted naturalists and bushmasters. Books and images of the heavens were thus part of childhood in an intimate way. Respect for nature and its nexus with the social / spiritual order from childhood experience became the matrix for the emergence of Hall the photographer.

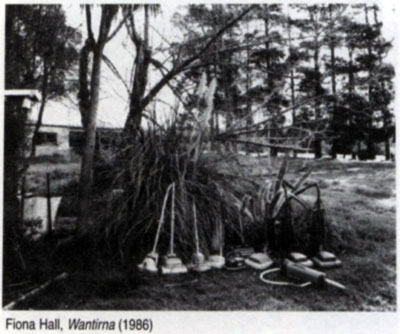

In the light of these elements of her education and background Hall's speculations on the relation of nature and culture are not so much theological - as ecological. Later works such as Wartime (1986) which continue the naturalistic mode are amplified my their location along site the concern with the Garden. In this image the pathos of the herd of discarded carpet cleaners on the lawn is that once we have made tile lawn, that artificial tribute to nature, we must cut the grass.

Similarly in regard to her earliest motifs, the chair and carpet in Leura are then not coincidentally - or solely - a confusion of patterns, a piece of visual wit, a questioning of representational securities, but also the consequences of tile Expulsion. Outside Eden we must build shelters and provide our own seats. Humankind, through humility or hubris, compensates for a lost intimacy with nature and the Creator through floral patterns. We are forever doomed to be creators of mere interior decoration.

Hall's dazzlingly inventive anti exquisitely crafted works deliver contradictory messages of hopelessness and wondrous human invention, tenderness and pain. The gnostics believed in an ultimate harmony of As Above, so below, the knowledge of which was denied to the laity. It rebound secular and religious, cosmic and mundane, pagan ants Christian systems.

What is the message of Hall's work: reconciliation or alienation? Should we try to read the images more closely?

* Since 1995 Hail has received even wider recognition as a contemporary artist. In 1997 she was awarded tile Contempora 5 Art Prize run by the National Gallery of Victoria and has published Subject to Change - a book of her own images and writing (EAF and Piper Press, 1995).

Two one person shows The Price is Right and Call of Nature by Lana H. Foil have been held at Roslyn Oxley Gallery, Sydney and her work included in major surveys.

Her work Occupied Territory was a commission for the Museum of Sydney opening in 1995 and she has also been commissioned to design a garden work for the National Gallery of Australia extensions opening, scheduled for 1998.

Notes

1 . Contemporary understanding of Hall's work over twenty years must acknowledge the fine analysis of Kate Davidson's mid career survey The Garden of Earthy Delights: the work of Fiona Hall (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia 1993) as well as her earlier group exhibition catalogue Stranger than Fiction: Contemporary Work with Photographs. (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 1992)

2. The pioneering historical study Australian Women Photographers ( 1982) by Barbara Hall and Jenni Mather was a largely self-funded (and poorly rewarded) project over many years which inspired and facilitated many small showings and inclusions of women's work in exhibitions land other studies. It has taken another decade for the first substantial monograph on the work of Olive Cotton (b.1911) from the 1930s to the present to appear Canberra: National Library of Australia: 1995 text by Helen Ennis). Ennis is also writing a biography of Margaret Michaelis-Sachs (1902-1985) who immigrated to Australia in the 1930's. A full monograph on Sue Ford has been published this year (Monash University Ad Museum curated by Helen Ennis).

3. 'The Movement of Women', Art and Australia (Vol. 33, No. 1, Spring 1996, p.62-69). Bodies of work by male professional photographers of the past such as Max Dupain were available in the seventies. Feminist retrieval projects had an impact in the 1980s but the many young women graduating from art school photography courses lacked role models. Both male and female photographic artists starting in the late sixties and early seventies lacked the example of an immediately older generation involved in contemporary directions who had begun work after World War II. Some of these like David Moore pursued photojournalism overseas in the fifties.

4. Sommer (b.1905) was born in italy of German/Swiss parents. He came to the United States via Brazil where his father was a landscape architect / Horticulturalist. Somme's work was not widely known until his major 1980 show Venus, Jupiter and Mars (Delaware Art Museum) and monograph by W John Weiss (London: Travelling Light 1980). Sommer who had trained as a landscape photographer was fascinated with Paracelsus (Philippus Von Hohenheim) a radical physician and chemist who based study on natural observation not tradition, but was a follower and inspiration to alchemical and mystic approaches to theology and cosmology.

5. The influence of Dame Frances Yates' publications on the role of visual imagery in the Renaissance virtually created a new discipline in oceanographical study, Densely academic in style, Yates' ideas captured the imagination of Marshall MCluhan and others involved with contemporary culture. The author is currently researching the influence of Yates' books on Australian artists such as Hall, Hewson / Walker, and Paula Dawson.

Gael Newton

Formerly the Senior Curator of Photography

National Gallery of Australia

more Essays and Articles

|