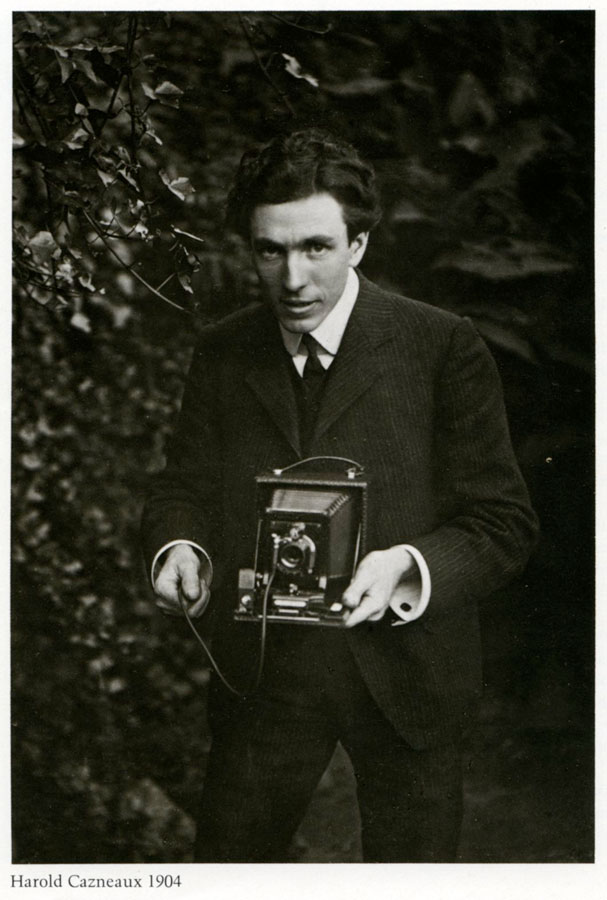

Harold Cazneaux

Cazneaux's Sydney 1904-1934

Biography Essay by Gael Newton

Originally published as the essay from

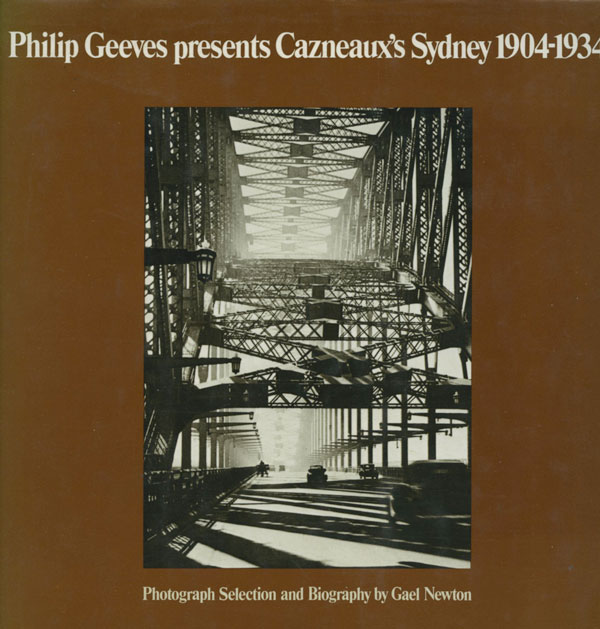

Philip Geeves presents

Cazneaux's Sydney 1904-1934

Photograph Selection and Biography by Gael Newton

The David Ell Press Sydney 1980

Harold Cazneaux's long and distinguished career as an Australian photographer stretched from 1904 when he began taking photographs until his death in 1953, although it is generally agreed that his most important work was done before World War II.

During this period, he produced a large and varied body of photographic work, both professional and personal. It embraced such diverse areas as portraiture, landscape, architecture, industrial and urban scenes.

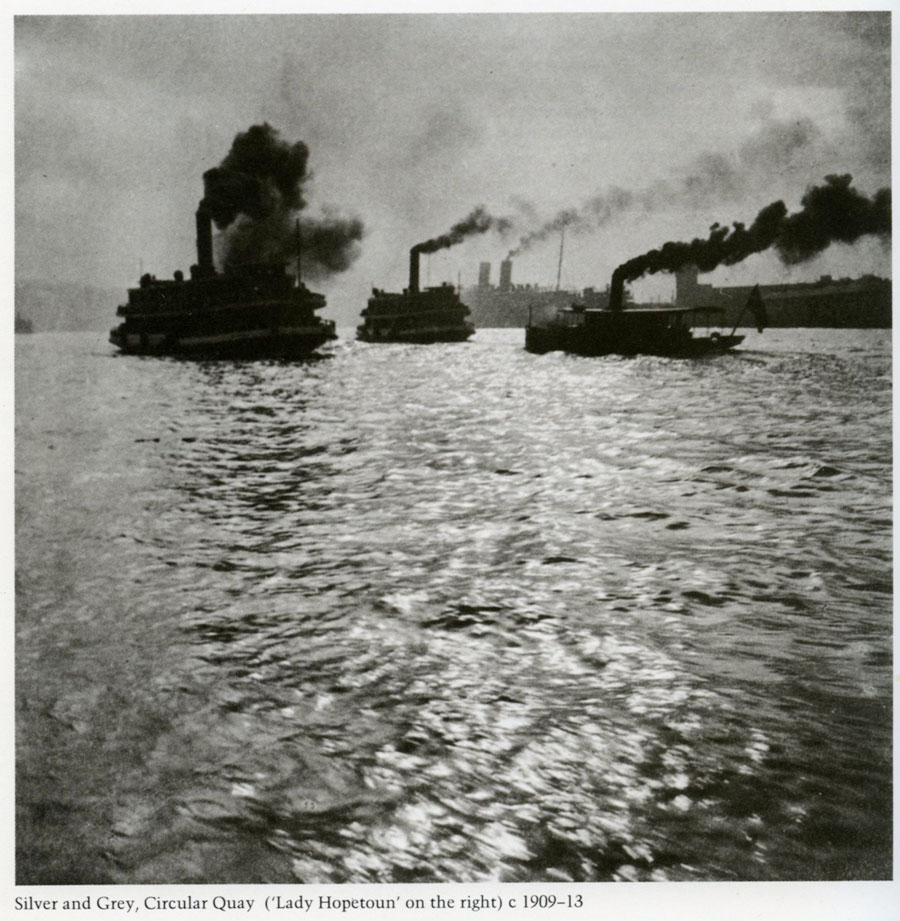

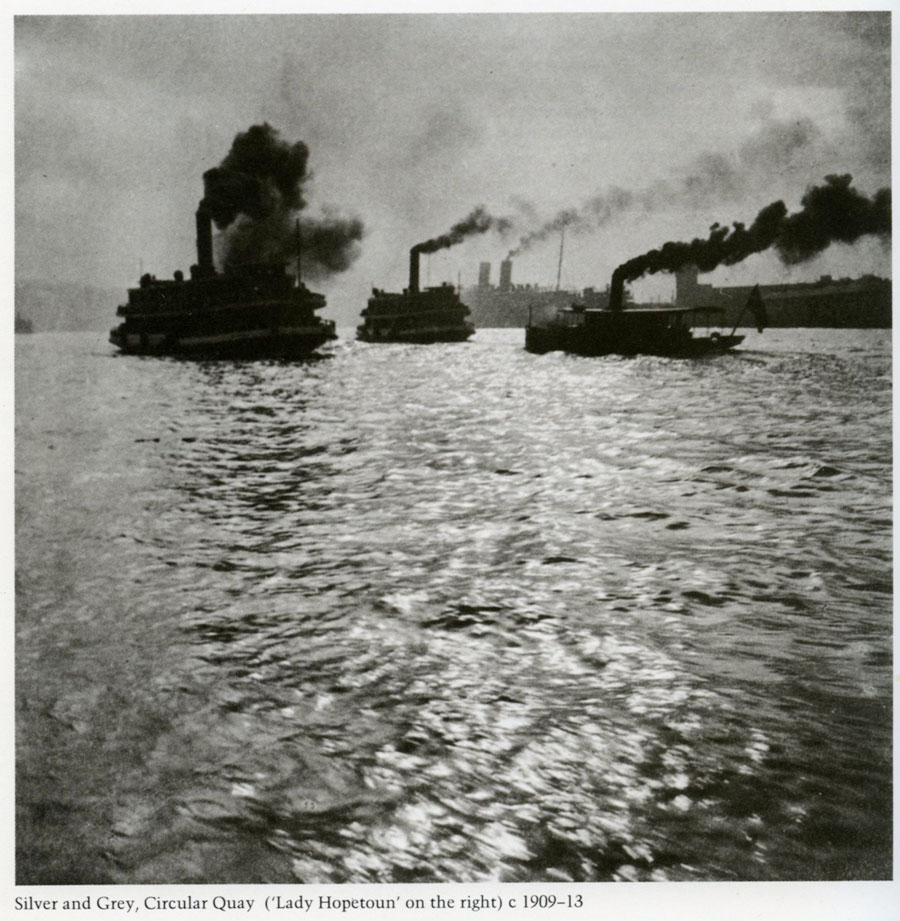

It is, however, for his pictures of Sydney that Cazneaux is best remembered. He photographed Sydney over thirty years and his work provides a pictorial record of the dramatic way in which the city changed in that time. |

|

|

It is, however, for his pictures of Sydney that Cazneaux is best remembered. He photographed Sydney over thirty years and his work provides a pictorial record of the dramatic way in which the city changed in that time. During this period Sydney changed from gas to electric power; from hansom cabs to motor cars; from a skyline dominated by terraces to the jagged peaks of modern buildings.

The demure ladies who wore ankle-length skirts in all seasons became sun-worshippers in brief swimsuits. Cazneaux's sensitive and evocative images reflect not only physical changes but also the transformation of the tone, character and way of life of the city.

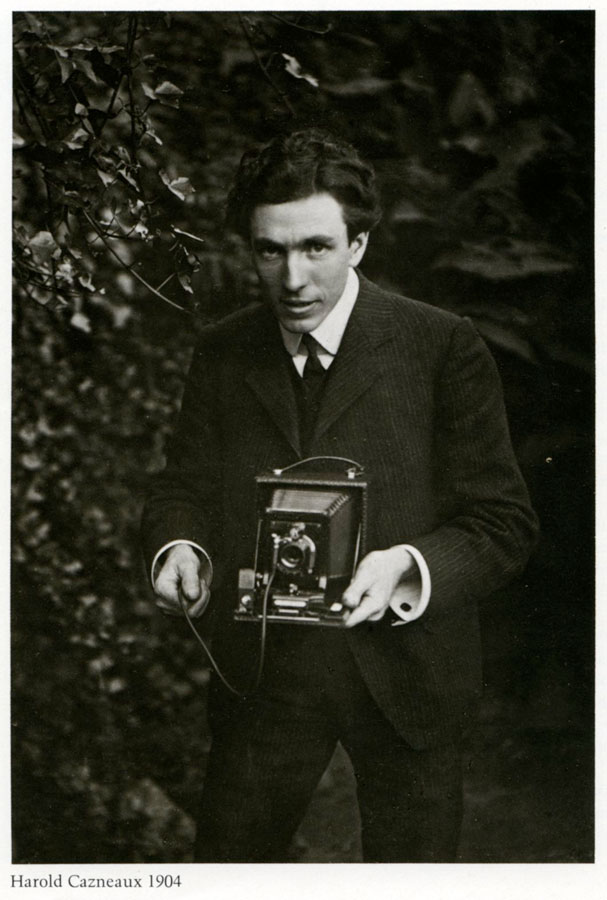

Harold Pierce Cazneau (he later added the 'x' to his name) was at first a reluctant photographer even though he had photography in his blood. He was born in Wellington, New Zealand, on 30 March 1878. His parents, Pierce Mott and Emma Florence Cazneau, operated a photographic studio. They had both worked in photographic studios in Sydney before going to New Zealand in 1876.

About 1887 the family returned to Sydney and, two years later, moved to Adelaide where Pierce Cazneau had been appointed manager of a portrait studio, Hammer and Co. When Emma Cazneau died in 1892, Pierce and his four children – Harold had a sister and two brothers – settled at Scotts Creek in the Adelaide Hills. Here Harold developed a love for the bush and the outdoor life and began to show signs of a talent for sketching. |

|

|

When Pierce Cazneau remarried in about 1897, the family returned to Adelaide and Harold joined his father at Hammer's studio working as an artist-retoucher. But the work was not congenial to Harold who detested being confined inside a studio and who was, moreover, much more interested in sketching than in photography. He enrolled in evening art classes at the Adelaide School of Design. His father hardly inspired him with a taste for photography for, although he was an able and respected professional, he did very little photography away from the studio.

An enthusiasm for photography was aroused in Harold when, on his way to art classes, he had the opportunity to see the exhibitions of the South Australian Photographic Society. The work of many of the Society members was in the style known as Pictorialism which was closely allied in spirit to the Impressionist movement in painting.

Indeed, Pictorialism was the first real 'art' movement in photography. It originated in England in the 1890s and its adherents sought to explore the potential of the camera so that, instead of being a mere recording device, it could become an instrument of artistic expression. It was developed by amateurs rather than professionals and emerged at a time when the High Victorian taste for detailed realism was on the wane and giving way to a preference for the Impressionist style, particularly that of J. M. Whistler, Aestheticism and Art Nouveau.

In sympathy with this new spirit, the Pictorialists turned away from the even lighting and fine detail of earlier photography and introduced into their images soft atmospheric effects, rather sombre tones and masses of simplified harmonious shapes. To achieve a graphic effect various processes were used to impede the detail and fine tone recorded by the camera, including the simple devices of leaving the lens out of focus or printing through chiffon.

For the young Cazneau, Pictorialism was a revelation. In its techniques he saw a way in which he could achieve with the camera the imaginative effects he strove for in his sketches. Years later he recalled how the 'new beauty of the camera' changed his attitude to photography and set him in a new direction: 'This was my start indeed. The instinctive urge was now fixed in my mind – henceforth all my efforts would be towards using photography as a medium of artistic expression and away from the Traditional Business side of the Professional Studios.' |

|

|

As Hammer and Co. seemed to provide no opportunity for anything beyond routine work, Harold sent some samples of his work to Freeman's studio in Sydney (where both his parents had worked earlier). He was offered the position of artist-retoucher at a salary of £2.2.0 per week. He moved to Sydney in 1904.

With his improved financial standing he was soon able to buy his first camera, a Midge Box quarter-plate. It was about this time, too, that Cazneau, flushed with optimism and with a touch of flamboyance, added an 'x' to his name.

Soon after, Cazneaux sent for Winifred Hodge, his sweetheart in Hammer and Co. studios, and the two were married in 1905.

Over the next few years, Cazneaux gradually built up a reputation. In 1906 the Australasian Photo-Review published some of his pictures and one of them, a study of rock fishermen against a breaking wave, won him £3.0.0 and enabled him to pay for a T. P. Amber half-plate camera.

In 1908 the same journal ran a special article about Cazneaux and in 1909 the Photographic Society of New South Wales, which he had joined in 1907, took the unprecedented step of mounting an exhibition of seventy-five of his pictures. This exhibition is believed to have been the first one-man show ever held by an Australian photographer. It was well received by the public, the press and local artists and established Cazneaux as a major photographer.

Among the more traditional forms of portrait and landscape studies, the exhibition included a number of city scenes in which Cazneaux was able to reveal the abundance and variety of interesting subjects that ordinary city life offered. These pictures were rather sombre in character and were notable for their richly atmospheric effects.

In 1910 Cazneaux gave further evidence of the abiding fascination which the city held for him when he wrote for the Australasian Photo-Review two articles called 'In and Around the City with a Hand Camera'. In these he urged photographers to explore the urban world and explained his own methods of working. He was an enthusiastic advocate of the small camera which allowed the photographer greater freedom of movement and enabled more spontaneous images to be captured.

Around 1916 Cazneaux and other progressive photographers, responding to a burgeoning sense of Australian nationalism, sought to establish a new school of photography based on natural sunlight. He was a founder member of the Sydney Camera Circle which dedicated itself to this end and to banishing the low tone 'greyness and dismal shadows' which characterised the English Pictorialism of earlier years.

While Cazneaux was enjoying an ever-growing reputation in amateur photography circles and taking a leading role in teaching and exhibition work, he was not given scope at Freeman's to express his talent in professional work. Cazneaux had never really become resigned to studio work but could not see how he would ever have sufficient capital to establish his own business. He had a large family by this time (five daughters by 1918) and could see no escape from the work he hated.

His health broke down, a misfortune which had a happy outcome as it prompted Cazneaux to resign from the studio. On his recovery he began freelance work, operating from the studio of Cecil Bostock, a fellow Camera Circle member, and developing his work at night at his home in Roseville. When Bostock's studio closed in 1920, Cazneaux began to work from his home.

His move into freelance work came at an opportune moment, for Sydney Ure Smith was establishing The Home magazine and offered Cazneaux the position of official photographer. Ure Smith had been a faithful supporter of Cazneaux since seeing his one-man show in 1909.

The Home and Ure Smith's other publication, Art in Australia, kept Cazneaux supplied with assignments to cover portraits, landscapes and urban scenes. The Home was designed to cater for the latest modern trends and co-editor Leon Gellert encouraged Cazneaux to experiment with pictures which captured the spirit of the times. Cazneaux was at last able to bring all his skills and talent to professional work.

In the late 1920s Sydney was developing rapidly into a modern city and Cazneaux's style, too, changed in a way which allowed him to reflect the changing nature of the place.

The soft and rather hazy visions of the city which typified much of his early work gave way to bright, clear light patterns and geometric shapes.

By 1928-9 he was producing such dramatic studies as the view of Martin Place (Plate 55) deeply cut by late afternoon sunlight and with its pattern of busy commuters.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge, emerging during its construction as an imposing form which dominated the cityscape, became a major theme in his work (see Plate 53).

He responded to the challenge of the New Photography from Europe of the late 1920s and early 1930s in which design and pattern were dominant and which led to the development of a new style of advertising photography.

In spite of these new themes and techniques, Cazneaux could not share the enthusiasm of the younger generation of 'modern' photographers, such as Max Dupain, for the pure forms of the Machine Age. Their work often seemed soulless to him.

For Cazneaux the city remained essentially a human place. In his scenes its inhabitants are rarely absent. And despite his concern with forms and patterns, his images are notable for their spontaneity and naturalness – a sense, not of a moment caught and frozen, but of movement momentarily arrested.

It is not appropriate to class Cazneaux as a Documentary photographer concerned with social or political conditions.

His work was not directed towards revealing the poverty of the slum children he photographed nor the hard labour of the wharfies. |

|

|

| Plate 55 Martin Place |

| |

|

| Plate 53 The Old and The New |

Ugliness of scene or society was not the subject of the Pictorialists. Their aim was to show the best side of the city by the creation of beautiful and imaginative photographs.

Cazneaux's pictures of Sydney, as well as appearing in various magazines, were used to illustrate many Ure Smith publications. These included the Sydney number of Art in Australia in 1927, Sydney Harbour, 1928, Sydney Streets, 1928, The Sydney Bridge Book, 1930, Sydney Surfing, 1929, The Book of the Anzac War Memorial, 1934, and special albums such as The Sydney Harbour Trust Album presented to the Prince of Wales in 1920.

In his late years Cazneaux cherished a wish that his old Sydney work could be published as a book and he spent a good deal of time selecting and preparing negatives and prints for this purpose. He was encouraged by the success of a selection of his work which the magazine Contemporary Photography published in 1948 under the title 'The Sydney of Yesterday'.

But the book project was not realised in his lifetime. It was not until 1978, when an exhibition entitled 'Cazneaux's Sydney' was held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, that interest in the project was revived. The present book, the result of that revived interest, represents the posthumous fulfilment of Cazneaux's wish.

GAEL NEWTON

Gael was Curator of Photography, Art Gallery of NSW 1974–1985

Click here for Harold Cazneaux main introduction page

or - more essays by Gael Newton AM

|