Australian Women Photographers: 1890-1950

(Australian Tour 1981-1982)

Gael Newton

This essay was written as the forward to the catalogue for the exhibition Australian Women Photographers: 1890-1950, that had an Australian Tour 1981-1982. The exhibition was staged at the George Paton Gallery in Melbourne, with the then Director Judy Annear. Click here for more on the exhibition.

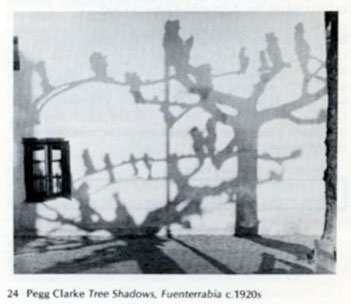

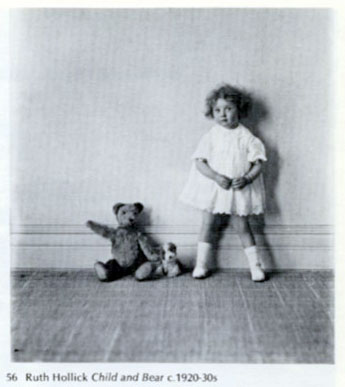

Over the last few years the Australian Women Photographers project has run parallel to my own research into the development of art photography in Australia (1890-1960). Between us there has been mutual interest, encouragement and collaboration, the latter in particular on photographers common to both projects; namely Ruth Hollick, May and Mina Moore, Pegg Clarke, Olive Cotton and Margot Donald.

It was assumed that quite different criteria would be involved in our respective overall selections for presentation.

As the researches are now publicly accessible it is interesting to consider relationships between these two bodies of work. My focus was on photographers visible in their own time. This was done by reference to exhibitions, publications and other indicators of self-conscious, artistic aspirations. Perimeters of traditional art history, such as tracing development of period and personal styles defined the field of view.

The Australian Women Photographers project seemed open-ended with a curiosity as to what women's work even looked like.

I expected their findings to reveal a kind of vernacular photography, reflecting the restricted physical and social sphere of women's lives before World War II. The question was also whether gender affected the totality of the image, or was an arbitrary category, likesay, 'one-legged' photographers.

In reality, this exhibition seems to have charted a territory between the realms of art and information in photography. The organizers wished to avoid simply prompting the belated inclusion of a few women workers into the art stream. There they would be promptly de-sexed as marketable products. However, the selection also seems to be readily accessible to the formal criteria of contemporary art photography.

The photographs being sufficiently organized or stylized to attract attention on a formal level. The exhibition is being shown in art museums and would no doubt be a welcome addition to any of their photography collections. This impression of some common ground is enhanced by the organization of the exhibition around the work of twenty-six women photographers with clear personal styles. In this way it approaches an art context more than would women's folk photography or occasional snap shots by 'Mum'.

A reading of the women's biographies reveals a familiar general pattern in the development of photographers: the gift of a camera at an early age. Photography is quite physically and financially demanding, though not highly regarded as a profession. It is not surprising then that the biographies show up a number of audacious and resourceful personalities. Both characteristics would have been required to work seriously in photography as a woman in those days.

In comparison, the biographies of pictorialist photographers of the period often reveal tame lives and a safe emotional distance between self and subject.

Despite their break with social convention in taking up photography (especially as a profession) the women's work is not radically subversive or unconventional. The world presented rather seems to show the status quo domestic life more sensitively than their male counterparts.

Perhaps because of the choice of a career in photography, such a life appears to have been denied to some of the photographers. It is a comfortable world reminding us that photography has always required time and some funds. There is an admitted preference for a quality of 'warmth', women and children as subjects, on the part of the exhibition organizers. This would seem to be a response to an emotional intimacy or rapport on a human level between many of the photographers and such subjects. By extension, this includes the viewer, who assumes the position of the invisible photographer.

Perhaps an unpretentious relationship could exist simply because their mutual low status as women cleared the air of ego and any desire to mystify the process of photography.

Any hard and fast examination of whether a feminine aesthetic exists generically or socially would require a hard cross-examination of the period in general, outside of art photography. The latter, in comparison with more naive work, usually appears very stylized and thus more distant.

This view is supported by examining the photographers in the exhibition most influenced by styles in photography.

For example, pictorialist Pegg Clarke and Dorothy Davidson's work (the latter obviously influenced by a thirties taste for geometric design) have least contact with the people in their pictures. Ruth Hollick and May and Mina Moore adopted conventions of Art Nouveau and the Aesthetic movement of the turn of the century. Hollick's elegant spatial harmonies and the Moore sisters' dark tonality and soulful expression seem high and low key variants of the era of Sargent's portraiture.

Yet both have that 'presence' lacking in their style models. Hollick's child portraits have an inventiveness and appeal lacking in her rival in this field, Harold Cazneaux, in whose work children become mere elements on a par with the gauze, flowers and light patterns. The Moores extracted the maximum of effect and personality from the minimum means in their head and shoulders only shots, by simple and subtle turns of the head. Considering the gross sterility of their contemporaries or even of current studio work, their achievement is impressive.

Hollick's two studies, one a formal and conventional view of bride as the demure virgin, the other an informal shot knees up on the studio stool, further confirms the impression this exhibition gives of cutting through style to a direct contact with the subject not found in other work of the period.

Final mention must be made of Lillian Louisa Pitts whose work evokes a J.H. Lartigue-like world of the Edwardian extended and comfortable family life (whose gaiety and security no doubt evokes a nostalgic longing in today's nuclear or solo parent society). The zany energy of Lillian Louisa Pitts' pictures arises from her relationship to the subject and a preference for repeated shapes; rows of ladies, ladders, and a patch of straw-hatted nieces and nephews sprouting like mushrooms in a field. Her art happily subverts sobriety, formality, art and artifice.

This exhibition furnishes us the enjoyable stimulation of unknown work, and re-evaluates what has been in most cases long neglected. No doubt some will also be commercially popularised. In gaining respect for the activities of these photographers it is important to ask what significance it has for women photographers today?

Not just for the new wave of those who are art school trained and career oriented, but for the respect and valuation of photographers outside this area. Perhaps a parallel exists between the goals of women and ethnic cultures: assimilation with the option of retaining heritage and identity. It is in a way the dilemma of photography itself, which is being so eagerly absorbed into the art world that the issue is confused as to whether 'good' and 'art' are synonymous terms.

Gael Newton

National Women's Day

March 1981

more Essays and Articles

|