In 1998 I drafted an essay for the Oxford companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture published in 2000 about the new developments in Indigenous photography through the 1980s–1990s. For reasons I cannot remember, I did not submit the essay.

That draft was expanded in 2006 as The Elders Indigenous photography in Australia for the exhibition catalogue for Michael Riley Sites Unseen at the National Gallery of Australia.

Please note: I have kept this unpublished draft more or less as I wrote it in 1998. That is, I have resisted updating it.

|

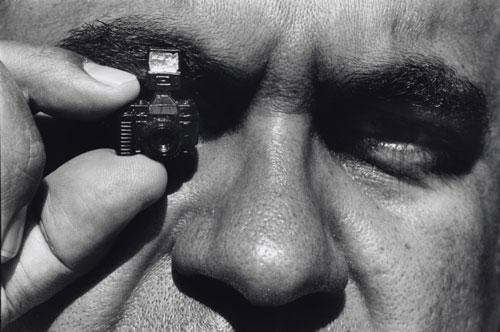

Mervyn Bishop: Is there an Aboriginal photography? 1989

Collection - National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

First Generation:

Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Photographers

Gael Newton AM, 1998

formerly unpublished

In 1986 a dynamic wave of urban indigenous artists in Sydney gave notice of their ambitions and style by staging the first contemporary art exhibition by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander photographers. The venue was the Aboriginal Artists Gallery in Clarence street, Sydney, and the exhibition part of the program for NADOC ’86 (National Aborigines and Islanders Observation Day Committee).

The exhibition included sixty mostly black and white photographs by ten photographers: Mervyn Bishop, Brenda L Croft, Tony Davis, Ellen José a Torres Strait Islander by origin, Darren Kemp, Tracey Moffatt, Michael Riley, Chris Robinson, Terry Shewring and Ros Sultan. The works included reportage to manipulated images, some with a sharp political edge.

It was not the first exposure of indigenous photowork, Koori ’84 a pioneering show of urban artists two years earlier had included photographers Riley, Shewring and Ian Craigie. At the same time as NADOC’86 a parallel photography exhibition of Aboriginal Images by ten Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal photographers was opened at the Aboriginal Artists Gallery in Melbourne on 10 September 1986. José, Moffatt and Sultan exhibited in both shows.

The 1986 exhibition photographers came from a variety of backgrounds and some were to move out of photography afterwards. Shewring, and Davis who were chiefly painters. Shewring was self-taught and involved with the new Eora Centre. Davis was a teacher from Western Australia and the most experienced of the group, having exhibited extensively in his home state. He worked in several media and had won the Bunbury art Purchase Prize for Landscape in 1974.

Ros Sultan also worked across media. Croft, José, Moffatt, Sultan and Riley were graduates of the booming art school courses in the 70s and 80s which over the previous decade had embraced photomedia in their curricula. Moffatt had already made short films and Sultan and Riley would work later in film.

Non-traditional fine art mediums like photography and video were established as serious disciplines in the 1970s and courses included introductions to new art and social theories of feminism and post-modernism and multiculturalism as well as some awareness of Aboriginal issues. The students of this era, report that they were not then encouraged to express their ethnicity or Aboriginality.

Curator Ace Bourke then Director of the Aboriginal Artists Gallery, and co-ordinator of the 1986 Sydney show affirms that the project was initiated and driven by the artists involved, in particular by the lobbying of Tracey Moffatt. Later as a Director of the Hogarth Galleries in Sydney, the first commercial gallery specialising in Aboriginal art, Bourke regularly exhibited the work of Riley and José as well as indigenous photographers who emerged in the 1990s.

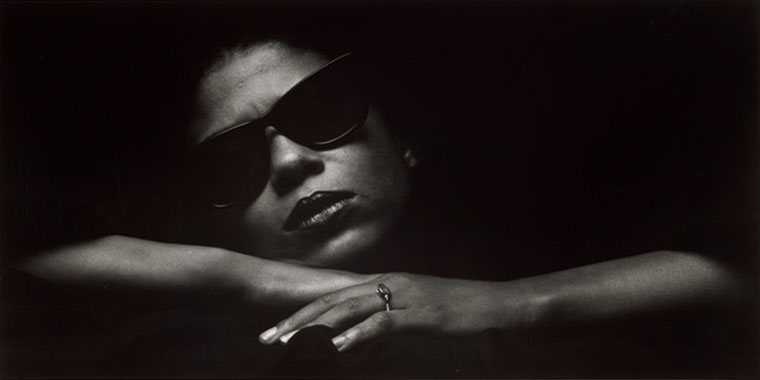

The NADOC’86 invitation card used Michael Riley’s moody Hollywood-style portrait of Kristina Nehm, a dancer with the Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre in Glebe. She enigmatically flaunts her sunglasses as a fashionable not functional accessory. Yet no magazine then would have used her image regardless of the international profile some black models enjoyed in the 1970s. Kristina’s glamour removed the image from the overt political and social commentary expected in representation of Aboriginal subjects. Ace Bourke, recalls Riley’s portrait ’…was very political, black girls weren’t meant to be seriously chic’.1

|

Michael Riley: Kristina 1986

Collection - National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

The Australian Centre for Photography (ACP) established in Sydney by the Australia Council in 1974 to promote a diverse range of photographic art, was alert to the significance of the 1986 show and published a review in their quarterly magazine Photofile in November. In 1989 Moffatt was first indigenous photographer to exhibit at the ACP.

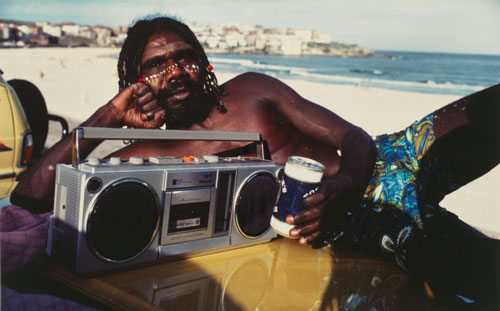

Moffatt’s work attracted the only press coverage. Her black and white series Some Lads showed dancers from the Aboriginal and Islander Dance Company nonchalantly, cheekily, passionately playing and posing; anything but the sobriety or anonymity of photographs of corroborees or even classical dancers. A colour image of dancer and actor David Gulpilil mimicked the stance of sunbaking beer-drinking Aussies at Bondi Beach. Of this image the artist made a rare categorical statement to the media; ‘Why shouldn’t aboriginal people go to the beach like anyone else’. The Gulpilil portrait so emphatically staged and plugging into stereotypes, announced the direction Moffatt would develop in her future work.

|

Tracey Moffatt: The movie star: David Gulpilil on Bondi Beach 1985

Collection - National Gallery of Australi, Canberra |

It could be argued that the post modernism in the contemporary art of the 1980s, with its faith in appropriation and disruption of the notion of an original pure canon, centre or method, greatly favoured the work of those formerly excluded women and / ethnic ‘others’ artists.

In 1989 Moffatt made Something More, a nine-part colour and black and white work that was a clearly staged quasi-narrative. Its central character a Eurasian country girl in outback Australia, was played by the artist. Her character aspires to gaudy glamour clothes and the excitement of the big city but she and her dreams are literally crushed on the road out of town.

Something More was made as part of a residency at the Albury Regional Art Gallery. The work’s overt stage-set backdrop and tableaux compositions, large scale and ambiguity of message was Moffatt’s departure from collusion with camera naturalism and the documentary traditions. The work’s visual and phonic strategies set the pattern for Moffatt’s subsequent decade of work in installation /series works which would alternate between seeming clear narratives and constellations of images reworked from the memory-bank of popular culture.

The meaning of story remains ambiguous. Were all women doomed or just non-Europeans? Was her own fear as an urban Aboriginal artist setting out to scale the heights of the art world, Moffatt’s own anxiety?

Raised as a foster child in a white family in Brisbane, Moffatt’s work plunders images and phrases from films, television, pop music mostly of the recent past and mostly to do with identity. Viewers of different cultures see their own image in her works which frequently mix Eurasian and Hispanic models so that the issues become generic to constructions of the native within western cultures rather than the specific details of racial politics of Australia.2

Moffatt has gained considerable international acclaim with her work handled by two highly respected Sydney contemporary art galleries. Her politics included the refusal to be categorised as an Aboriginal woman-photographer suspecting as she did with the NADOC show, that attention came from tokenism not engagement with the proposition that the works in the show all simply take their place within contemporary art.3

Other indigenous photographer’s shows followed in the next five years, aided by the establishment of dedicated venues such as the Boomali Artists Co-operative. New indigenous photo-based artists and curators appeared. Michael Riley has been active in film and exhibition work a powerful large scale colour series of manipulated still life titled Sacrifice shown at Hogarth Gallery in 1986, was a step away from documentary. Jose also an activist, works across media and has made powerful video work In the Balance in 1995.

Destiny Deacon, a descendant of the KuKu (Far North Queensland) and Erub/Mer (Torres Strait) peoples, now based in Melbourne, began exhibiting in 1990. Her work is characterised by low tech satire with kitsch objects and dialects amalgamated. She has appended the term Blak to her titles, and employs a kind of creole phrases across her works. In doing this she retrieves the issue of ‘speaking proper’.

|

Destiny Deacon, Blak lik mi 1991/2003

Collection - National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

Deacon also acknowledges the role of television, film and popular culture in shaping her life and imagery.4 Her use of kitsch in particular black dolls, became a recurrent motif. Some images can be pointedly political as in Ask yr’ mother for sixpencethat shows a ‘black mama’ servant in between the monstrous phallic tower of the Melbourne Casino under construction. Some of her works apply to both white and black experience as in the Three wishes triptych where a black fairy princess in black tutu is left with the wand and the baby.

Moffatt and Deacon deliberately ground their works in the issues of dress and undress which are central to how the native is seen (and not seen). These issues are present in the viewing of photographs of and by indigenous people. As feminism argued everything to do with women is inflected.

These references to self-presentation are also present in the work of Brenda L. Croft and Fiona Foley, both sophisticated artists in several media. Croft’s 1988 black and white photographs were direct and tough, an Aboriginal boy is photographed with his T-shirt proclaiming ‘Cook who? /Cuckoo.’

Croft also made use of family photos and inscribes word and sounds in her works. Her large portrait series on contemporary Aboriginal women and their families was also influential making points about rights to glamour, career and motherhood as did her large work on sensuality. Foley most recently presents herself naked to the waist reconstructing old fashioned native belle postcards. It was not necessary to know the artist, as the manner of the photographs made a personal point about a collective past.

Alana Harris who continues major projects works for AITSIS, has received Heritage Art Awards for her landscape work and recognition for her ongoing work portraying Aboriginal people. She most recently worked with Carol Cooper on the 1997 Portraits of Oceania exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, curated by the Judy Annear.

Leah King-Smith from Queensland and more recently Rea are among artists who have emerged since the mid 1980s. King-Smith’s late 1980s colour montages re reanimated old photographs of Victorian Aborigines which she re-embedded in bush settings. These images were seductive and widely reproduced on covers such as that of Art and Australia. The latter the first time for an indigenous photographer. King-Smith had cibachrome photographs included in the 1997 international exhibition curated by dealer Gabrielle Pizzi, Metamorphosis : contemporary Australian Aboriginal photography and sculpture at the Palazzo Papadopoli, Venice.

Rea, has a tough 90s edge to her work in the skill of her digital imaging and the bite of her use of language and addressed issues of gay politics. She links colours to stereotypes and emotions. Brook Andrew’s powerful image I split your gaze (1998) is indicative of the latest sophisticated directions in indigenous photo-arts. A scholar, artist, gay and black man, he works across media and borders in doing so defying that these artists have the confining labels and limits of the past.

Despite Moffatt’s deft strategising to continue work with certain themes and subjects, without being re-confined as an Aboriginal woman art photographer, her work and all the indigenous artist-photographers use subject matter related to issues of identity.

One of the most noticeable features of the work of Moffatt, Deacon and Rea is their ear for the inseparable nexus of imposed categorising words and images. They cannot begin from a tabula rasa in quite the same way that an earlier generation of non-indigenous new wave photographers in the seventies could imagine themselves taking up a ‘new’ medium as if the medium had no history. This was far more complex for the indigenous artists. For this first generation of highly directed artist-photographers to begin meant inevitably that first there would be some backtracking.

To conclude with Bishop’s question: Is there an Aboriginal photography? Patently yes

Links:

Urban Focus essay National Gallery of Australia

Koori Art '84 and NADOC '86

Artists mentioned above as listed in Design & Art Australia online database:

Alana Harris, Rea, Leah King-Smith, Tracey Moffatt, Michael Riley

Ellen Jose, Ace Bourke

Footnotes:

- Conversation with the author June 1997. Portrait of Kistina at the Portrait Gallery. Another glamour portrait was of Tracey Moffatt, both held National Gallery of Australia.

- See author’s biographical essay Fever Pitch ,Piper Press, Sydney, 1995.

- See her exchange with curator Clare Williamson in the show 1994?

- See Virginia Fraser, ‘Destiny’s Dollys’, Photofile, no.40, November, 1993, pp.7-11

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles |