|

| On the Yarra |

Based on original David P Millar's text

from the Art Gallery of New South Wales booklet

for the exhibition in Sydney 1st November - 14th December 1980

References to Australian photography at the turn of the century must always include N.J. Caire of Melbourne. As a specialist in scenic views, Caire established a strong reputation in his lifetime—a reputation that still continues.

Jack Cato, the chronicler of Australian photography, and a portrait photographer of distinction noted, "Often I've had to study a print of his a second time to make certain it was not a copy of a painting. His rich subject matter, his fine composition, and his mellow tonal qualities seemed to be too good for a photograph".1

Few Caire plates are left, and although there are reasonably sized holdings of his prints in Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra, they are but a fragment of a life time's work. Details of Caire's life are elusive, and in some cases seemingly contradictory. Cato's The Story of the Camera in Australia gives a racy account of a charming personality, but cannot disguise the lack of important facts that would assist us in explaining and assessing Caire's work.

In 1858, the ship "Bee" arrived in Adelaide on 10 October from the United Kingdom. On board were many assisted immigrants, including Caire's father, also named Nicholas John, his wife Hannah, and six other children. The shipping records note that Nicholas John, senior, was a 46 year old Guernsay-born agricultural labourer. Nicholas John, the future photographer, was now aged 21, having been born on 28 February, 1837.2

On his arrival in South Australia, N.J. Caire jnr. was to be swept up by enthusiasm for the camera. He received instruction from the flamboyant photographer, Townsend Duryea. This New Yorker had started a photographic business in Melbourne before moving to Adelaide. Here he combined studio work at 66 King William Street with an investment in a copper mine at Walleroo, S.A.

Caire soon felt confident enough to start out on his own, and the South Australian Almanac and Advertiser for 1867 carried an advertisement stating that N.J. Caire, "Photographer and artist", was now established at 67 Hindley Street, Adelaide, and offering portraits in various styles for 1/- upwards, or "Carte de Visits" at 10/- per dozen. The Carte de Visite was the life blood of the photographer's business.

Measuring about 7.5 cm x 5 cm, the size of a visiting card and sporting the photographer's name on the reverse side, these cheap, multi-portrait photographs were in much demand. They were collected and inserted into highly decorated, leather-bound albums whose outside format was indistinguishable from the family bible.

By the 1870s the fashion was changing. The Carte de Visite was supplanted increasingly by the larger size, the Cabinet, measuring 10x14 cm. In his treatment of portraiture, Caire showed initiative. Cato reports that Caire was the first to break the family group stereotype by dropping the full length formula, massing the heads together and vignetting them off at the shoulders.

A few of Caire's Carte de Visite have been found in the State Archives of South Australia, showing faded, and somewhat predictable images of public buildings and street scenes. Other popular subjects, such as local dignitaries, entertainment personalities and State politicians and Governors would also have been taken by Caire for insertion in celebrity portrait albums.

For three or so years Caire worked in Adelaide, until the opportunity came for greater advancement on the goldfields, whereupon he moved to Bendigo and Talbot, and re-established his wet-plate portrait business there. The goldfields seem to have been a lucrative area of work for photographers. At the height of the rush, the English economist, Stanley Jevons, who was also an amateur photographer, noted in a letter to his sister from Sydney in February 1859.

"The diggers were highly amused at being taken, and only required a hint to stand in any desirable attitude, so that my pictures seem almost alive with real diggers. When out in the field I am quite pestered with people wishing to buy views, and if I carried printing materials with me I might easily travel scot free as an itinerant photographer." 3

The peak of the gold rush hysteria lhad died down by the 1870s, Caire obviously now had sufficient reason to believe that there were quicker profits to be made on the goldfields than remaining in Adelaide.

|

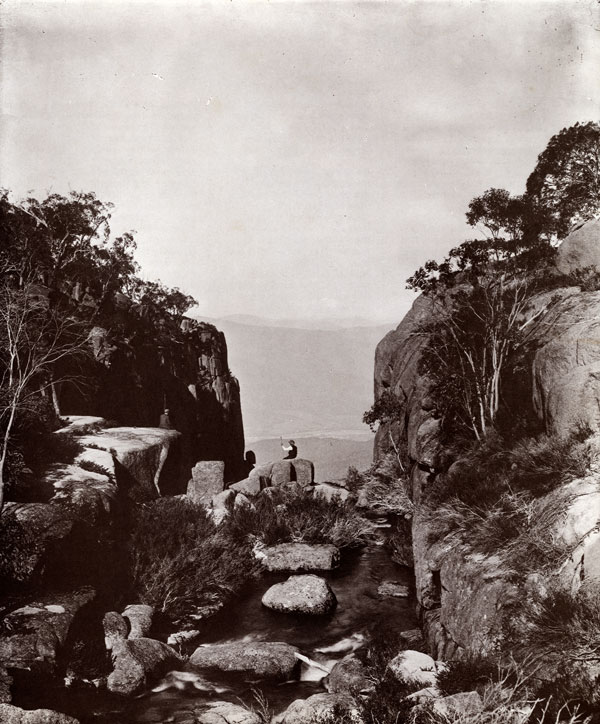

| Buffalo Gorge |

In 1876, Caire moved from the goldfields to Melbourne, and settled at Sherwood Street, Richmond. By 1880, Sand's & McDougall's Melbourne Directory noted that 11 Royal Arcade Studio, Bourke Street, once the business address of Thos. F. Chuck & Sons, was now in the name of N.J. Caire—a situation that was to last for four years. Obviously the profits from the goldfields must have been considerable for Caire to have purchased such a select business in such an enviable position.

In 1884, N.J. Caire was not listed at 11 Royal Arcade, and was described only as a "landscape photographer". He had obviously decided to go it alone, as no other record of a town studio is ever to be found. Caire had shown an early interest in landscape photography. There are reports in Cato of his taking wet plate scenes of Aboriginals, Lake Tyers and "good landscapes of the tree-lined roads rolling away to Strzelecki Ranges". 4

Caire's enthusiasm for the view trade was one shared by the Australian market. From the invention of the collodion wet-plate process in the 1850s, view photography had become increasingly popular. Views were often issued in sets or mounted in albums, and then sold through studios, bookshops or stationers. Topographical or scenic, they were usually severely limited in scope— townscapes, picturesque walks, exotica, public buildings or farm settlements. Of such a genre is Caire's View of Bendigo, Views of Victoria, and Gippsland Scenery, all to be found in the La Trobe Library, Melbourne.

The invention of the dry-plate process revolutionised view photography for Nicholas Caire, as it was to do for everyone. Its faster exposure times, its packages of prepared plates, marketed first in Adelaide in 1881, and in Melbourne in 1884, and the need no longer of developing the plate as soon as it was exposed, was a boon to landscape photographers.

Caire was quick to dispense with boring studio work, and by 1884 he had sold out to L. Grouzelle et Cie., owned by a Frenchman, who was to become the Melbourne master of retouching and tinting photographs. Caire now aged 47, began operating from his house at Darling Street, South Yarra.

Caire had already exploited the economic possibilities of the scenic view earlier than the advent of the dry-plate. In 1878, prior to taking over Chuck's, he was manager of the Australasian Photo Company at 57 Bourke Street East—a company that specialised in producing albums of views, complete with captions and comments, and one with which he had already served his apprenticeship as an operator.

In 1888, Caire was appointed official photographer to the Royal Commissioners of Melbourne's International Exhibition. Along with the famous and prolific wet-plate master, Charles Nettleton, he exhibited scenic views in the Victoria court.

Caire had not always kept good health, his stomach causing him almost constant pain. About 1888 he visited a doctor, who urged him to give up drinking tea. The success of this simple treatment launched the 51 year old Caire on to a fitness and diet programme. It was a step which brought him into contact with a new movement—a movement that took good health seriously. 5

It campaigned against alcohol and smoking, and urged exercise, plain food, and vegetarianism. It preached the virtues of fresh air, regular bowel motions, and salads, and denounced condiments, patent medicines and tight corsets. Combining a medical opinion with puritan stoicism, it was a movement that was to become increasingly popular. In Australia its mouthpiece was the magazine Life and Health, whose advertisements urged the sickly to visit, either the Sydney Sanitorium at Wahroonga or the Warburton Sanitorium in Victoria, to purchase Sanitarium Health Foods, and to eat at Sanitarium Cafes.

Its Seventh Day Adventist background was important for the production of Life and Health, but as it was implicit rather than explicit, the reader will search in vain for any denominational theology in its pages. Much of the movement's teachings would later be adopted throughout society as normal medical and domestic practice, particularly in infant and child care.

Caire became a strong supporter of both the movement and the magazine, and from 1911 until his death in 1918, a large number of his photographs were reproduced in it. That Caire saw his scenic photography increasingly in ideological terms is apparent by the titles to these pictures which he wrote, either himself, or found acceptable. Thus, a picture of men and boys collecting wattle on a bank is titled, "Wattle-gathering is a good stimulant to appetite". 6

A picture of the Avon River, Christchurch, N.Z. has the caption, "Fresh air is one of Natures Remedies",7 whilst a scene of a Maori house has the unwittingly amusing comment that such a building "does not require much artificial ventilation". 8

It was not only in an ideologically orientated magazine as Life and Health that Caire's attitude towards clean and open living was expressed. In the La Trobe Library, Gippsland Scenery contains several photographs whose titles leave it quite clear as to what Caire intended the reader to take from the photographs. For instance, no.39 entitled "Packing Fish" extols the virtues of a healthy outside occupation by stating that "the Fishermen of the Lakes are a Fine Race of Men—Stalwart, Healthy and Robust".

He subtitled no.51, called "Caire's Camp", with the statement that in "searching for the Picturesque in his bush travel", the photographer has "slept under the canopy of Heaven in huts and tents, with and without blankets". It was a statement not to arouse pity, but to excite emulation.

|

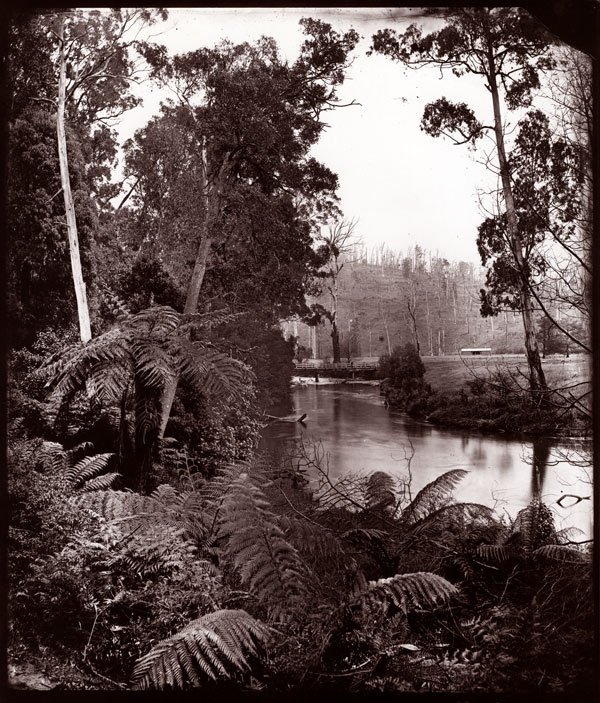

| Upper Yarra |

Caire's love of scenery had a two-fold basis. First, it was a love for "picturesque", which for him was the rain forests of Victoria and the mountains of the Great Dividing Range. Secondly, it was a belief in the efficacy of healthy exercise and fresh air. It was a popular belief that the air of the cities was not healthy for people—that diseases and general debilitation were the lot of those who breathed in the air of the crowded terraces and tenements of the city.

By the late 19th century, State Governments felt compelled to do something about this, and accordingly began to establish national parks, such as the Royal National Park, south of Sydney, established in 1879.

Although we know now that the smoky, polluted air of the Victorian city was less a source of disease than contaminated water, inadequate sewerage, low standards of food hygiene and bad diet, this simplistic medical belief was unquestioned by those who trumpeted the advantages of ozone at the beach or the cool air of the mountains.

Microbiology was yet in its infancy. Erroneous or not, Cairo's photography was a perfect instrument for extolling visits to the beauty spots of Victoria. The Victorian Government had, before the economic crash of the 1890's, covered the state in a network of railways. These provided the working man and his family with cheap day excursions.

Caire was especially charmed by the area of Healesville, Black Spur, Narbethong and Marysville, fifty miles north of Melbourne. Another great Victorian photographer, J.W. Lindt, shared his enthusiasm, and between them they did much to popularise the area amongst day-trippers.

In 1904, with Lindt, he wrote a book Companion Guide to Healesville, Black's Spur etc, advising of walks to be enjoyed, the trains that would get you there, and the scenery to be relished and photographed. The publication was illustrated with photographs by both Lindt and Caire. He later also illustrated Victorian Railway handbooks entitled Picturesque Victoria, How to get there.

If by the turn of the century, Caire's searches for the picturesque were made easier by the multiplication of road, rail, bridges and tunnels, it was not always so. In his early travels in the late 1870's, especially when encumbered by wet-plate technology, Caire struggled through the rain forests in search of waterfalls, fern gulleys, rivers and rapids.

Thus, in his attempt to photograph Erskine River Waterfall at Cape Otway, Caire and two guides spent five days getting themselves, the photographic apparatus and six mules to and from the 750 foot waterfall he wanted to photograph. On the trip through Myrtle Creek, near Black Spur "the dray loaded with stores required six horses to draw it two miles in eight hours". Isolation was another problem before the advent of the railways, but whilst moving by horse through the empty forests of Gippsland and the Great Dividing Range he would stumble across splitters, "lonely individuals", who "obtain a lucrative employment in the production of laths, firewood and post and rail fences".

Such was Howard at Worley's Creek, "who lives a life of seclusion, and whose only neighbours are the wild dogs and snakes, or the lyre birds, all of which are numerous in this wild retreat". 9 (Cat.no.6)

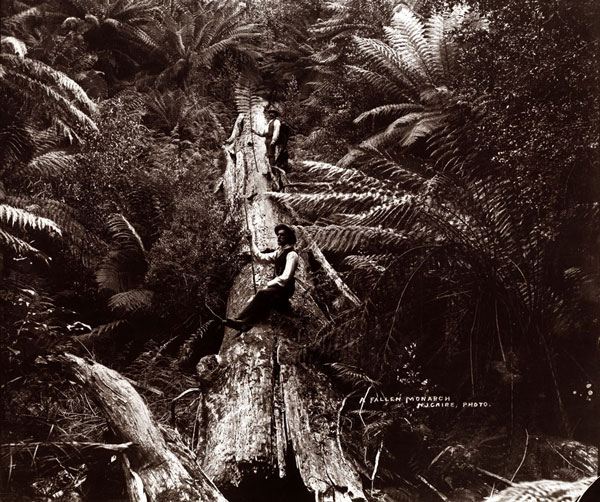

Caire developed a great interest in the trees of the rain forests of Victoria. It was an interest that became an enthusiasm, and he viewed with increasing concern the loss of these forests to the bushman's axe and the selectors' fires. Speaking in 1905, he urged that "some steps should be taken to protect the few remaining giants from destruction either by bush fires or the hand of man".

Some of these Blackbutt trees he reckoned to be between 1,500 to 1,800 years old, while the size of some of them was remarkable— "Uncle Sam" at Black Spur, to mention but one, he estimated to be 250 feet high and with a 40 foot girth. But as he ruefully noted, "The Selector, usually a rough and ready man, with but little poetry or sentiment in his otherwise sturdy character, is oblivious to the origin and history of these great plants, his one desire being to see his land cleared and grass growing for the sustenance of his stock". 10

His love of the bush was in the tradition of English landscape romanticism. Not the turbulent and 'sublime' romanticism of J.W. Turner, whose paintings of mountains inspire the sense of the numinous, and whose storms arouse awe, but the gentle romanticism of the John Constable and William Wordsworth.

Hence his love for fern-filled gullies, bubbling brooks, splitters' huts tucked in romantic clearings and country roads curving past rich foliage. Not that he eschewed mountains. In 1888, with the assistance of the newly formed Bright Alpine Club, he climbed to the top of Mount Buffalo. With the help of his two guides Caire was lowered or hauled by ropes into various positions with his 12x10 camera to get the best points of view. (Cat. nos. 28 & 29)

But none of these pictures are dramatic or 'sublime' in the way that Frank Hurley of a later generation would have made them. They remain human in scale and picturesque in treatment. It was this gentle English romanticism that inspired Caire throughout his life, a romanticism he linked with a belief in the basic goodness and moral purity of nature.

|

| Mrs. Kirkwood's Gully |

Although he was a great reader of the Australian writers, 'Banjo' Paterson and Henry Lawson, his view of Australia is of the moist, coastal areas—the landscapes of the day-tripper on leave from his city office. There are no mobs of cattle, shearers, 'swaggies', artesian bores or a parched, flat landscape covered in mulga and burnt by the midday sun. In a period of Australian history when romanticism for the outback was being made into the national myth, Caire stays with his coastal gums, beech forests and fern valleys watered by streams and waterfalls. (Cat. nos.22-26)

His Australia is green and lush. It is therefore not surprising that he should visit the West Coast of New Zealand and its Fiordland prior to World War One. There was plenty of the picturesque and green in that country to please the eye of this charming romantic.

The dark side of romanticism, with its concern for transience, death and decay, was inspired by the destruction of the trees of the rain forest—either fallen to the splitters' axes, or standing gaunt as the result of fire or ringbarking. English romantics might populate their landscapes with the melancholy ruins of Tintern Abbey or Paestum's temples – Caire populates his photographs with great but doomed trees that arouse a wistfulness that such monuments of nature are being, or will be, destroyed. (Cat. no.20)

People do not dominate Caire's landscapes. Often they do not appear at all. Yet when they do, they fit into the landscape photograph as a small, even if integral, part of nature. They are tucked under ferns, sit beneath great trees, stand shoulder high in the undergrowth or appear as diminutive figures in a forest clearing. (Cat. nos.8&9)

For Caire, harmony of man with nature was a perfect state. The only time man dominates Cairo's landscapes is when nature has been butchered. Man now stands triumphant on felled trees (Cat. no.17), suffers Blackbutts the ultimate indignity of being temporary bridges over mountain streams (Cat. no.32), or turns the stumps of trees into ludicrous houses for Gippsland selectors (Cat. no.18).

Even when the land has been cleared, and man has imposed his order on the Gippsland environment, nature seems to reassert herself. In photographs on fruit farming, raspberry or currant picking in the National Library of Australia, man and nature seem to have struck a balance, which produces pictures of considerable picturesque quality, with man and nature merging into a state of balance and serenity.

The studio photographers, especially those like Kerry & Co. of Sydney who became closely allied with the postcard trade, produced genre scenes as well as views. Genre pictures were intended to either make a point or arouse an emotion. Cairo's genre pictures emphasise the importance of the healthy life, the grandeur of the man who embraces the simple life in the bush, and the heroic quality of those who receive knock-backs whilst pursuing these goals. There is none of the lonely pessimism of Frederick McCubbins' bush-genre paintings. At the worst, Cairo's genre are but temporary setbacks in a life of vitality and inner peace. A comparison of Frederick fMcCubbin's Down on his luck, painted in 1889 with Cairo's photograph of the same title establishes the point very well'. 11

The Heidelberg painters, Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin, Charles Conder and Arthur Streeton occasionally visited some of the spots that Caire photographed. But in moral overtones and atmosphere, Caire's work is much more akin to a Melbourne painting of the earlier 1870's. The dark rich tones of Caire's plates, his love of ferns, forests and streams, are possibly more reminiscent of such paintings by Eugene von Guerand as Ferntree Gully on the Dandenong Ranges, 1857, Waterfall, Strath Creek, 1862, and Figtree on American Creek near Wollongong, 1861, than the highly toned works of the Heidelberg painters, with their sparse undergrowth, patches of high-toned sky and dry vegetation whose roots are rarely bathed by passing streams and cascading waterfalls.

To read the instructions Caire gave to other photographers is to see why his photographs differ from the Heidelberg painters. He urges towards overexposure. "Nothing is more unsightly than an underexposed fern picture ... Remember that to see the Bush in its photographic glory you should see it on a dull day ... Don't be afraid of over-exposing. Remember that in the bush you are photographing almost exclusively green objects, and that the actinic power of the light is considerably reduced owing to the nature of the surroundings".12

It is highly likely that Caire and the Heidelberg painters knew each others work. But Cairo's preferences for grey days, mellow tones and rich detail, a semi-religious respect for nature, and a relative indifference to genre photography, marks him out as sui generis.

|

| The Hermit's Camp near Marysville |

Caire's method of working was very unusual. His contemporaries worked {from studios, supported by a number of operators and dark-room staff. It was the golden age of the studio photographer— Crown Studios, Kerry & Co., Falk Studios— yet Caire, when he left 11 Royal Arcade, preferred to work from his home. That this attractive individualist more than survived is attested by the way he moved through to the top of Melbourne real estate. In 1877, he was living in Richmond, a suburb of working men's cottages and factories.

By 1880, he was at 2 Formosa Terrace, Barkly Street, St. Kilda—very middle class. In 1884, he was living in select South Yarra, first in Toorak Road until 1894 and later in Darling Street in the same suburb. 13

Despite his economic success, it is hard to believe that Caire could possibly have survived, let alone prospered, by simply tapping the view trade. The nineties were a period of great economic hardship, and the shrinking of discretionary incomes affected photographers very badly. Even Caire's great friend, J.W. Lindt, backed up by strong promotion, a large studio, and a vast portrait business in Melbourne, was forced by the depression to close his doors, and open a guest house in Black Spur.

An undated, unsourced newspaper cutting in the La Trobe Library asserts that Caire had farming interests in the Gippsland area. Such an interest, if true, may well have helped to eke out what must otherwise have been a plummeting income from photography.

Few of his negatives remain. Caire destroyed many during the Great War when because of a shortage of imported glass, he was compelled to clean the emulsion off his negatives, preferring to sell most of the pictures already framed.

Caire died in March, 1918, at the age of 81. He left behind five children, investment property in Paidham Street, Prahran, and two cameras, which he willed to his daughter, Edith Florence Caire. 14 He also left behind a reputation as an assured and masterly photographer.

David P. Millar Sydney, 1980.

|

| A Fallen Monarch |

Click here for more on David P Millar

Acknowledgements This collection of work by N.J. Caire was the result of a discovery by Dr. Don Pitkethly, Research Officer for Kodak (Australia) Pty. Ltd., of 42 glass plate, 10 x 12 negatives behind the stage of the social hall at Kodak's Coburg factory, a discovery which Gael Newton of the Art Gallery of NSW inspected and whose great significance she realised.

It was an exciting find as the number of Caire negatives still in existence is minimal. None of the plates were titled, but by perusing the Copyright Collection at La Trobe Library, Melbourne, and albums at Canberra's National Library and Sydney's Mitchell Library, as well as tourist-type publications of Edwardian Victoria, the greater number have now been identified.

John Cato of Melbourne has kindly filled in a few gaps existing in the Kodak collection from plates in his own possession. The result is an exhibition which sums up all aspects of Caire's work. One of the difficulties facing any critic or historian of photography is to differentiate between the information contained in a print, and what the photographer intended as its message.

There is often more information in a photograph than an operator needs to get his message across, and it is often difficult for the observer to decide what constitutes the message, and what information he is to disregard as superfluous. Happily, in the case of Caire, there is enough in writing by Caire himself to be assured of what he intended his photographs to convey.

Information on Caire is very elusive. For instance, claims that he was married in Adelaide in 1870 have not been proved by the Registrar of Deaths, Births and Marriages in S.A. A claim in one newspaper report that he had farming interests in Gippsland have also not yet been proved. The arrival of his family in 1858 is listed in the official records, but does not include the name of J.N. Caire, the future photographer. Yet no shipping records for S.A. lists any other Caire as having arrived in Adelaide at a different date! The Post Office Directories do not list the addresses that Caire lived at whilst working in the goldfields.

This exhibition was made possible through the assistance of Gael Newton, Curator of Photography, Art Gallery of New South Wales, who invited me to undertake this project, Nigel Lendon of the Sydney College of the Arts, Allan Davies of the Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, Barbara Perry of the National Library of Australia, and the staffs of the La Trobe Library, Melbourne, the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and the Archives, State Library of S.A. My special thanks to Don Pitkethly and John Cato who printed the works from the original plates, despite the grave tonal problems that exist when one uses aging plates and unsympathetic modern papers.

David P Millar

All the prints listed are in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The owners of the negatives are acknowledged, with thanks. All the plates are 25 x 30.5 cms. When research did not disclose the correct title of the view, a question mark is placed after the title, pending its confirmation. All photographs were taken after 1878, and probably by 1900.

REFERENCES

- Jack Cato The Story of the Camera in Australia, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1955 p.79

- Shipping Returns, State Archives, State Library of S.A.

- W.S. Jevons Letters and Journals, Macmillan, 1886, p.120

- Op.cit. p.76

- Life and Health, Aug-Sept, 1914. pp226-230. Article "Is tea a beverage, injurious or otherwise?"

- ibid, Oct-Nov. 1911

- ibid, April-May 1913

- ibid, Dec-Jan. 1912-13

- N.J. Caire. Views of Victoria, C1878, passim. Mitchell Library, Sydney

- Victorian Naturalist, vol xxi, 9,1905 Article "Notes on the Giant Trees of Victoria", pp122-5

- Art in Australia, Vol 17, no 3, March 1980. Article "The Heidleberg School and the popular image" by Leigh Astbury.

- N.J. Caire and J.W. Lindt Companion Guide to Heaiesville, Black's Spur etc, 1904, pp63-66.

- Sands and McDougall's Melbourne Directory, 1877-1918

- Last Will and Testament. Registrar of Probates, State Government of Victoria.

The list of exhibition prints

A. ABORIGINALS

1. Aboriginals off to Lake Tyers. Cato Collection

B. FLINDERS

2. Cape Schanke and Lighthouse, Flinders. Kodak Collection

C. MARYSVILLE, BLACK SPUR DISTRICT

3. A Settler's hut? Cato Collection

4. A tree bridge? Kodak Collection (Figure probably N.J. Caire)

5. The Hermit's Camp near Marysville. Kodak Collection

6. Splitters Hut, Morley's Track, Fernshawe. Kodak Collection

7. The Fairy Scene. Black Spur. Cato Collection

8. Condon's Gully? Cato Collection

D. GILDEROY DISTRICT

9. Miss Kirkwood's Gully, Gilderoy? Kodak Collection

10. Road scene, head of Blacksands Valley, Gilderoy. Kodak Collection

11. Scene at Cobham, near Gilderoy. Kodak Collection

E. WARBURTON DISTRICT

12. Timber tramway at Warburton. Kodak Collection

13. A Gold Digger's hut near Warburton. Kodak Collection

14. Curve on the Gembrook Railway. Kodak Collection

15. Scene on the Yarra, near Warburton. Kodak Collection

16. Scene near Warburton. Kodak Collection

F. GIPPSLAND

17. A Fallen Monarch. Kodak Collection

18. Giant tree utilized as a house at Wynstay, South Gippsiand. Kodak Collection

19. Giant Tree Gate Posts, Gippsiand Farmer's Garden. Kodak Collection

20. Tall Dead Giant Trees, Gippsiand. Kodak Collection

21. Dead Tree, Gippsiand. Kodak Collection. (Nos. 19, 20, 21 taken on the same property).

G. THE YARRA

22. On the Yarra. Kodak Collection

23. Upper Yarra—a country home. Kodak Collection

24. Upper Yarra. Kodak Collection

H. CAPE OTWAY DISTRICT

25. Big Stony Creek. Falls, Lome. Kodak Collection

I. MT BUFFALO DISTRICT

26. Bright. Kodak Collection

27. Gold Digging on the Ovens River. Kodak Collection

28. Fails, Buffalo Gorge. Kodak Collection

29. Buffalo Gorge. Kodak Collection

30. On the road to Harrietville. Kodak Collection

31. General View. Eurobin Creek. Kodak Collection

32. The Crossing? Kodak Collection |