A

web site dedicated to Keast Burke

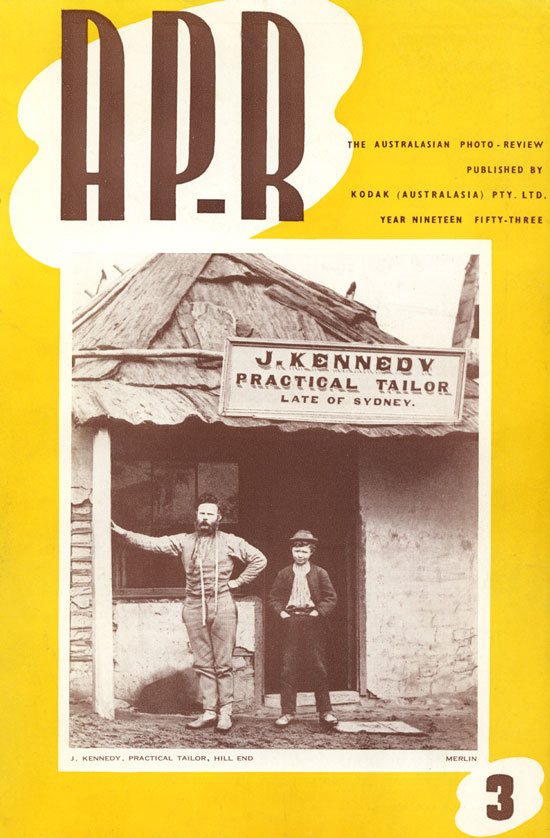

Beaufoy Merlin

Keast Burke's article on Beaufoy Merlin in the A.P.-R #3,

1953

Gold and Silver

By Keast Burke

Being the story of the

association of Bernard Otto Holtermann with Beaufoy

Merlin and with Charles Bayliss

and of the

photographic collection which resulted therefrom.

"In the great days of the gold rushes, many a photographer

left behind studio and darkroom to join in the great

search - but sure Holtermann must have been the only

gold-miner who neglected his gold-mining in favour of photgraphy.

He can be ranked perhaps as Australia's first and greatest

amateur of photography, using that word in its original

French sense. He liked the art for its own sake yet

reallsed perhaps more than he knew, its great documentary potentialities.

Furthermore, he did not hesitate to spend a vast sum

upon a great series of photographs designed to convey

to the world at large the story of the colony's extraordinary

material progress. He believed that by doing so he

could, in some small measure, repay his adopted landfor the

many favours it had conjurred upon him."

JACK

CATO

The

quotation is from some unpublished mss. by Jack Cato

in connection with his forthcoming work "The

Story of the Camera, in Australia."

INTRODUCTION

On

one fateful day during the winter of 1922, two distinguished

Egyptologists stood outside a doorway in Egypt's

famed Valley of the King. For them it was an anxious

moment,

knowing that that doorway had been sealed for three

thousand five hundred years. Would this be just another

disappointment?-with nothing disclosed but a few

discarded trifles left behind'in haste by some early

tomb-robber?

The

two were not to know that soon they would be gazing

in awe and in rapture upon a storehouse

of

ancient cultural

treasures the like of which the world had never before

seen.

Some

thirty years later two Sydneysiders were destined to

stand outside a small suburban backyard

shed;

it had been locked for more than a generation,

its contents

almost forgotten, its key long since lost. Their

anticipatory feelings were hardly on the same plane

as their predecessors

but at any rate there was to be no doubt as to

the eventual

value of their discovery-the dramatic revelation

of a life and culture almost as forgotten as Tutankhamen's.

Here,

neatly stored in fitted cedar boxes were incredible

numbers of negatives, records that were

in due course

to disclose every detail of the lives of our

gold-fields pioneers-the men, the women and the children,

their

homes, their business enterprises, and their

mining shafts,

the populous towns and larger cities.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Of

all the arts of mankind, that of the photographer

is inevitably

both the most lasting and the most

perishable. Marble and canvas possess some

degree of physical strength

but the cameraman must entrust his treasures

to perishable paper and film or fragile glass.

An

oil painting

is likely to be treasured as an heirloom

or possible "Old

Master," but only too often are old photographs "just

old photographs" to someone charged with "tidying-up." Occasionally

Fate intervenes, as she is also so apt to

do in the lives of mortals, but seldom has

she been

so watchful as in

the present instance; those who have followed

this story since its inception still have

some little difficulty

in believing that it is all true, that this

marvellous thing can possibly have happened-and

the reader

may well share that view. It is a long story

and one dependent

on many, many fortunate coincidences-each

one more astonishing than the preceding.

But of all

these happenings we recognise

as the most important the part played by

photographer Beaufoy Merlin.

Chapter

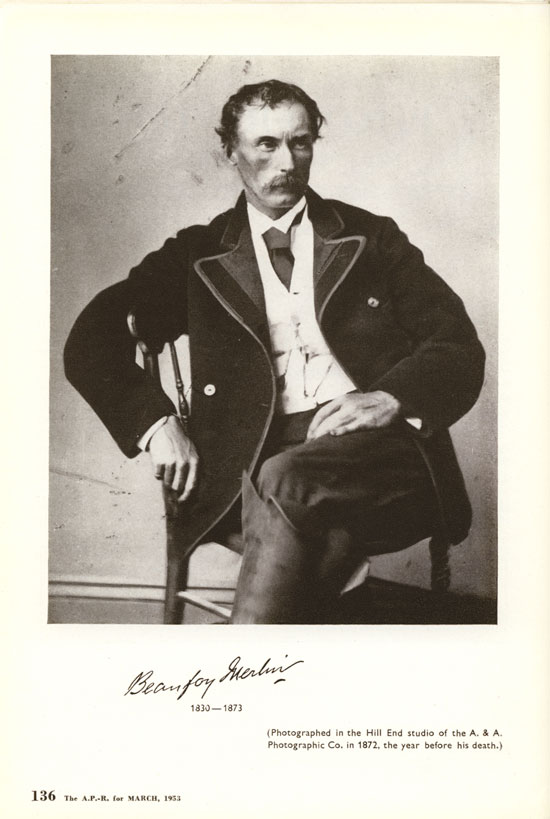

One Beaufoy Merlin

Of

Beaufoy Merlin we wish we could tell more than we can.

After

eighty years the written records have become

scanty. We have his portrait, made perhaps a year

before his death; it shows a sensitive, artistic nature,

yet

one not lacking in purpose and driving force. Above

all, we have his life's work - or, at any rate, a

substantial portion of it. The images carried on those

thousands

of carte-de-visite wet plate negatives show that

he was a born photographer, one who combined an excellent

technique with a documentary outlook that is astonishingly "modern" by

to-day's view. One thing is certain, and that is

Merlin's photography was not just a matter of "bread-and-butter";

he was a born artist and one who always gave of his

best.

Henry

Beaufoy Merlin was born in 1830, the son of an English

chemist by name Frederick Merlin - the

Beaufoy

being perhaps his mother's maiden name; by the time

he arrived in Australia he was nineteen years of

age. Of

his young manhood we know little, but it can be suggested

that his interest in photography arose from the family

association with chemical science, for in those days

almost every chemist dabbled in photography. That

interest may also have been reinforced from another

quarter.

There

is a strong family tradition of association with Ballarat,

and it is certainly a fact that there were

Merlin families living in that city as far back as

the mid-fifties. The Post Office Directory for 1868

shows

an entry for T. Merlin, Photographer. It may well be

that these folk were relatives and that they afforded

hospitality to

young Beaufoy when he first landed.

He

appears to have established himself as a field

operator under the trade-name of the American & Australasian

Photographic Company and to have travelled

throughout Victoria. On these trips he made numerous

records

of the scenery, but his specialty seems to

have been house-by-house

photography. The scheme was to give a few day's

notice to the householders of the area so that

they could

array themselves, ready for the camera, in

their 'Sunday-best.'

In

1863, then being thirty-three years of

age, he married Louisa Elliott Foster and

there were

four

children of

the marriage, all of whom appear to have

had interesting and adventurous careers-but that

is another story.

Our

first documentary information regarding Merlin comes

from a Vice-Regal letter still in the possession

of family descendants. As was the custom of the photographers

of those days, he had presented the Governor of Victoria,

Sir John Henry Manners-Sutton, with an album of photographs,

and it is clear that this letter of acknowledgment is

no perfunctory routine, but one of real appreciation.

The date is October, 1869, and it shows Merlin to have

been well established as a travelling photographer; of

value to us is the fact that it refers to Merlin's plans

for the extension of his sphere of activities to other

parts of Australia.

Government

Offices, Melbourne. 7th April, 1869.

Dear

Sir,

I am directed to convey to you the thanks of His Excellency the Governor

for the very handsome book of Photographs which you have presented to

him, and which he especially values as containing so many interesting

views of the places which he visited in his tour through the Western

District last year. The

Governor desires me to request that you will

let me know the name of your agent in Melbourne

through whom His Excellency may be able to

procure copies of the views which you propose

to take in other parts of Australia.

Faithfully

yours, (Sgd.) J. S. ROTHWELL, A.D.C.

Whilst

exact dates remain uncertain, everything appears to

have moved along as Merlin had planned. Some time in

1870, with the Victorian interests of "A. & A." in

the hands of a very young but capable assistant, and

one whom he had personally trained, Merlin set forth

for that wider field which he had so long envisaged.

We pause to wonder whether he could have had any anticipation

of just what lay in store for him-a bare three years

of life-span, but three years of crowded activity and

of positive achievement. He could have had little inkling

that his work in New South Wales would establish him

as perhaps one of the greatest documentary photographers

of all time.

The

Sydney directories of 1871-1872 provide us with some

information, listing the American & Australasian

Photographic Company as being in business at 324 George

Street, at 377 Riley St., and also at 11 Barrack St.

Apart from that there is internal evidence to show

that during portions of 1870-1871 he was carrying on

with his outdoor photography in Sydney. Of special

interest is the picture of the General Post Office,

showing the building just completed, the scaffolding

having been removed - this would be in 1870. Other

photographs depict familiar harbour scenes, some of

them most pleasantly 'pictorial' in their treatment,

while others show the arrival and docking of sailing

vessels.

But

even as Merlin was setting up his 10" x 12" wet-plate

camera along the quiet foreshores and on harbour vantage

points, the tenor of life was destined to be disturbed.

The cry was once again Gold! Exactly twenty years after

those first eager rushes to the Ophir and the Turon,

the tempo was again quickening all through the area.

And then there was the new field at Gulgong, appearing

even more promising.

The

principal gold-bearing areas of the day in N.S.W.

lay approximately within (or around) the triangle

Bathurst-Orange-Mudgee, the first-named place being

about one hundred and fifty miles west of Sydney.

Though he must have had many predecessors, the credit

for the first discovery of gold goes to Edward Hammond

Hargraves, who found payable gold in a creck (which

locality he subsequently named Ophir) about nine

miles from Orange. The Turon area is to the north

of Bathurst, the principal centres being Sofala,

Hill End and Tambaroora. Gulgong lies further north,

some sixteen miles beyond Mudgee.

Photographers,

like everyone else, must live, and it is not surprising

to learn that Merlin's caravan was soon carrying his

cameras and equipment along that well-worn road that

runs westward across the Blue Mountains. Let us pause

a moment as we travel this same route at fifty miles

an hour by car or air-conditioned express, to think

back to the days of horse travel. Beyond the rail-heads,

of course, an efficient service was offered by famous

coaching companies; by changing horses every ten or

fourteen miles, some fifty or sixty miles a day could

be covered according to the terrain. For the private

traveller and the teamster it was a quite different

proposition.

Normally

he had but the one set of animals and these had to

be properly cared for at intervals

during the day and at nightfall; he was, therefore,

fortunate if he was able to maintain an average of

twenty miles a day or thereabouts. There was a substantial

degree of expense involved too. As today, those who

provided food and drink and accommodation for man

and beast had to be reimbursed. Special services might

be required as well-harness to be repaired, swingle

trees to be replaced and horseshoes to be re-nailed.

Merlin's

first picture-making stop appears to have been at

Hartley on the Cox River, across the mountains.

Of that Hartley series just two are reproduced, but

those two are more than sufficient for the realisation

of his outstanding photographic ability. Everything

was grist that came to Merlin's mill; every scene

was a subject for him. Normally there had to be human

beings

in the field of view; then, as to-day, people were

possessed with a deep appreciation of their personal

likenesses and Merlin's posing ability was always

gentle, persuasive, artistic and confident. His sitters,

despite

the necessity for a 'hold it' of some five or ten

seconds, were always naturally grouped with little

sense of

strain. So much for the demands of business; in addition,

there were many which were obviously taken solely

for his own artistic pleasure.

And

now on to Gulgong. just why he selected this new field

instead of one

or the other of the more

obvious

three Turon towns is not quite clear; he was perhaps

deterred by the latter's comparative inaccessibility.

Coming as he did from the established cities of

Melbourne and Sydney, Gulgong must have made a great

impact

on his ever-susceptible 'documentary' outlook.

The town

was indeed a strange one and we to-day, as we study

Merlin's photographs, can share something of his

reactions. The Gulgong of 1871 was veritably

an American gold-fields

town.

"Gulgong

was certainly a rough place when I visited it, but

not quite so rough as I had expected. There

was an hotel there, at which I got a bedroo-

to myself, though but a small one, and made only

ofslabs. But

a gorgeously grand edifice was being built

over our heads at the time, the old inn being still

kept

on

while the new inn was being built on the same

site. The inhabited part of the town consisted of

two streets

at right angles to each other, in each of which

every habitation and shop had probably required but

a few

days for its erection. The fronts of the shops

were covered with large advertisements - the names

and praises

of the traders - as is customary now with all

newfitngled marts: but the place looked more like a

fair

than a town - perhaps like one of those fairs which

used to

be temporary towns and to be continued for

weeks - such as some of us have seen at Amsterdam and

at Leipsic.

But with this difference-that in the cities

named the old houses are seen at the back of the new

booths,

whereas at a gold rush there is nothing behind.

Everything

needful, however, seemed to be at hand. There

were bakers, butchers, grocers and dealers in soft

goods.

There were public - houses and

banks in abundance. There was an

auctioneer's

establisLment, at which

I attended

the sale of horses and carts."

(Australia

and New Zealand, by Anthony Trollope.

Chapman & Hall,

London, 1873.)

Those

were the days when the miners and those who catered

for their economic needs followed the gold strikes

around the world; as the Australian fields came into

the news at the very time when the Californian fields

were slackening, the direction in which world interest

turned is obvious. Clearly there was many a skilful

carpenter aboard those Pacific ships and soon those

tradesmen were busily at work.

For

the main part they would care to work the wet-plate process in the field the

year round, through burning summers and piercing

winters. Merlin possessed, of course, that necessary

asset,

a wet-plate coating caravan; in fact, at one stage

he appears to have had at least two (perhaps three).

One was constructed on a light buggy "chassis," while

the other was a two-horse vehicle of more substantial

build. Both had permanent false roofs which permitted

a current of air to pass between the roof and the

coating chamber-a most desirable precaution. And,

of course,

Merlin was not working single-handed in his enterprise.

He had a driver for the caravan - we see him in many

of the photographs, standing by with a spare dark

slide

in his hands. Later on, he had at least two assistants;

their services would be needed for studio operating,

plate-coating and for floating and printing the large

sheets of albumen paper.

Merlin's

sphere of activities also covered the smaller satellite

villages that

had grown up at the various

mining fields around Gulgong. Where for generations

cattle had grazed peacefully, there was now a population

larger perhaps than that of the Adelaide of its

day, and it dwelt in what we to-day would call "shanty

towns"-but let us not be'deceived-those people

lived in homes of bark because no other building

materials were available. Most of these settlements

took their

names from the rich alluvial leads near which they

grew up. Such were Black Lead just northeast of

the town, and Home Rule and Canadian Lead about

six miles

to the south-east. And there were many others.

All of these were visited in due course and photographs

obtained of dwellings, hotels and business premises

of every description.

Nor

did he fail to visit the diamond fields on

the Cudgegong River (five miles to the west of

Gulgong)

and first-rate, even by today's standards, were

the pictures he brought back from there. He photographed

by the hundreds mining shafts and their miners,

hopeful

or successful as the case might be; and the results

appeared to sell very well. That we know for

certain for the precise Merlin has left us his sales

records,

these being carefully marked on a slip of paper

glued to each and every negative. Of the mining

subjects,

perhaps the most valuable for its record value

and news interest is one of the two which we

have reproduced,

for it shows the happenings regularly associated

with a new "strike." Other photographs

show, in actual operation, a variety of types

of almost forgotten

mining equipment as, for instance, the various

devices for ventilating-a definite necessity,

for many of these

shafts descended hundreds of feet into the earth.

"Of

course, having come to Gulgong, I had to see the

mines, and I went down the shaft of one, 150 feet deep,

with my foot in the noose of a rope. Having

offered to descend, I did not like to go back from

my word

when the moment came; but as the light of

the

day faded from my descending eyes, and as I remembered

that I

was being lowered by the operations of a

horse who might take it into his brutish head to lower

me

at

any rate he pleased - or not to lower me

at all, but to keep me suspended in that dark abyss-I

own that

my heart gave way, and that wished I had

been

less courageous. But I went down, and I came up again

- and I found six or seven men work! It the bottom

of the

hole. I afterwards saw the alluvial dirt

brought up from some other hole, puddled and ing hed

and the

gold

extracted. When extracted it was carried

away in a tin pannikin-which I thought was detracted

much from the splendour of the result.

"Of

the men around me some were miners working for

wages, and some were shareholders, each probably

with a

large stake in the concern. I could

not in the least tell

which was which. They were all dressed alike, and there in

was nothing of the master and the man in the tone

of their

conversation.

Among those present at the washing up, there were two Italians,

an American, a German, and a Scotchman, who I learned

were partners in the property. The important task

of conducting the last wash, of throwing away for

ever

the stones and dirt from which the gold had sunk,

was on this occasion confided to the hands of the

American.

The gold was carried away in a parmikin by the

German."

(Australia

and New Zealand, by Anthony Trollope-Chapman & Hall,

London, 1873.)

Towards

the end of the year a most novel assignment came his

way. He had always been recognised

as one of Australia's leading outdoor photographers (in

those days there were not very many of them), and, in

consequence, when the New South Wales Government of the

day required a photographer for The Victorian-New South

Wales Eclipse Expedition of 1871, it did not hesitate

to select Merlin for the job. This was the total eclipse

of the sun of December 12th, the occasion being Australia's

first great effort in that branch of scientific enterprise.

The

site chosen for the observation was Cape Sidmouth,

in Northern Queensland - half - way between Cape York

and Cape Flattery. It was midsummer and the temperatures

were unexpectedly high. It was 140 degrees in the dark

tent; at noon the sun was vertically overhead and no

shade could be found for the tent, while on every side

there was glare from the dazzling coral strand. No

wonder

that, on many occasions, Merlin's plates dried out

before he could get them into their processing solutions.

As

for the eclipse, rain clouds obscured it for the whole

of its totality excepting a tantalising second or two.

However, Merlin brought back some interesting locality

pictures, including one of the Queensland coast that

he obtained from the expedition steamer; the latter

was satisfactory enough to lead Merlin to place before

the

Victorian Government some eminently practical (bilt

long ahead of their time) suggestions for the use of

photography

in coastal survey work.

The early autumn saw him back in Gulgong. The evenings were drawing in and business may well have been becoming slack, with new subjects for photography to be found only in the more distant south-eastern leads. And then, one afternoon perhaps, Merlin was approached by a wellattired stranger, his waistcoat adorned by a heavy gold chain carrying two miniatures or lucky charms; this person he had never before observed in the streets of Gulgong. The visitor was a shortish, rather sad-looking individual with a sparse beard, yet very much a man of ideas and practical enterprise, and one who had survived many vicissitudes.

After a few mutual words, it appeared that the two could meet on common ground. The stranger was very much interested in photography - and he was a wealthy man; in fact, a very successful gold-miner. Merlin, on the other hand, was the practical photographer in search of new avenues for his enterprise. What better project could a wealthy miner undertake than to arrange for the effective photographic coverage of Australia's progress? What fine publicity for Australia (and for the wealthy miner) such a collection of photographs would be when exhibited in the cities of the world? No sooner discussed than it was all agreed upon.

Merlin would leave at once for Hill End and there establish a studio that would make available the regular A. & A. house-by-house and studio services. As soon as that was done he would commence work, as his patron's personal photographer, on the much broader scheme of picturing the greater cities of Australia's south-west. He would photograph, in the largest possible negative proportions, their streets, their public buildings and their industries. In this way the story of Australia's extraordinary material progress could be recorded and prepared for exhibition throughout the great centres of U.S.A. and the Continent.

Beaufoy Merlin appears to have reached Hill End in the autumn of 1872 and to have started operations immediately, but it is unlikely that he spent the whole of his time there in view of his interstate interests and the field undertaking referred to above. He probably left Hill End, for the last time, about March or April 1873, that fact being confirmed by his photography of the decorations arranged by the citizens for the visit of Sir Hercules Robinson, the State Governor, on March 11, 1873.

By the autumn of 1873 his health must have been failing rapidly and he returned to Sydney, spending his last days in one of those familiar two-storeyed terraces in Leichhardt. He passed away at the early age of forty-three of "an inflammation of the lungs," almost certainly tubercular in origin, on September 27, 1873, and was buried in the Church of England cemetery at Balmain.

And so, the Beaufoy Merlin story draws to its close. One cannot help thinking . . . if only he had known how magnificent was his work, how well preserved against the ravages of time would be his negatives and, finally, how well they would respond to modern sensitized papers and modern enlarging methods, giving 'contact quality' at 4 to 15 diameters. If only he could have seen the great travelling exhibition of his work and the interest it was destined to arouse throughout the world ....

* * * * * * * * * * *

Before we bid farewell to the old days, let us bring the background up-to-date. On the fields (and elsewhere ' ) a scattering of old men and women in their eighties and nineties are living today, most of them with keen minds, vivid recollections and a wealth of tales. The descendants of the miners are legion; in Sydney, as like as not, two out of every five at a luncheon table will tell you of their forbears of the Turon. Gulgong still stands, sharing with Mudgee the pastoral prosperity of the rich alluvial flats of the Cudgegong. Surprisingly enough, as one walks the characteristic narrow curving streets of the town, one notes on almost every hand buildings whose detail of construction bears undeniable evidence that their erection goes back to those first days when the throng of carpenters busily sawed and nailed the boards of pine into 'false fronts' of surprising variety. Quite a number of the buildings actually photographed by Merlin can be recognised without much difficulty, though, in most instances, their days are numbered. Incredibly enough, there is still one building which ante-dates to the gold-rush days by some ten years-it is the original accommodation house and posting station for the teams and other road travellers bound for the north-west.

Black Lead, just north of the railway line, remains a name on the map and many a high mullock heap is to be seen, mutely reminding us of the strenuous labours of the deep-lead miners.

At Home Rule, some six or seven miles to the south-west, digging is still in active progress, but all of it is for clay (of both the building and pottery varieties). Any of the locals will be happy to point out to you the very spot where four Irishmen found the first gold and without hesitation named their claim Home Ride.

Canadian Lead to its west is barely recognisable, for there the pits were shallow and mostly they have been filled in by the graziers.

Moving down to Tambaroora you will find it hard to reconstruct the town from a,few pine trees, a single chimney and one or two overgrown cemeteries.

Southwards across Fisher's Hill there is still a Hill End, and the wattles in their season still blaze in Golden Gully where the prospectors coming down from Hargraves met those coming up Oakey Creek from the Turon. What remains of the town dozes sleepily on its great Hawkins Hill spur high above the river. It enjoys a magnificent setting as the everchanging light plays on the slopes of the valley and on the river fifteen hundred feet below. The views are magnificent; there are many that say that the Split Rock outlook is the most beautiful in Australia. To the west, Sargent's Hill bleeds scarlet from a thousand erosion scars but the impression is softened by the rich greenery of the avenues of great shade trees planted 'by Beyers and Mayor Hodges, to say nothing of a generous sprinkling of orchard trees everywhere. Of the buildings photographed by Merlin, a handful have managed to survive the passage of time but to-day's observer is likely to be hard put to recognise some of them.

As for gold, one is more likely to encounter a boundary rider than a fossiker as one moves about the surrounding countryside. Nevertheless, a panful of gravel taken at random from any creek is likely to show a few colours in the dish. It is good fun, but undeniably strenuous; after washing half-a-dozen dishes most City dwellers would consider they had done a good day's work.

There is little local employment and it is difficult to see from whence could come any new enterprise. Hill End does not want a tourist industry and probably it is unlikely to have one. There are no golf links and there is plenty of better fishing than the Turon's. Casual walking is hardly to be encouraged by the steep slopes everywhere and the thousand unfilled, unfenced shafts would be something worse than a nightmare for parents. In any case, those fifty odd 'V.H.' miles from Bathurst will ever deter all but the most confident and well-equipped drivers.

But hope still runs strongly among those good people of Hill Endand we share those hopes . . .

(To be concluded in the May issue)

17742:

Here we see the familiar Hartley Court House as

it was

early in 1871. The central figure

appears to be

the P.M., Thomas Brown, who retired in the

same

year after sixteen years' service. The

building was erected

in 1837 and remained in active use as a court

house for half a century.

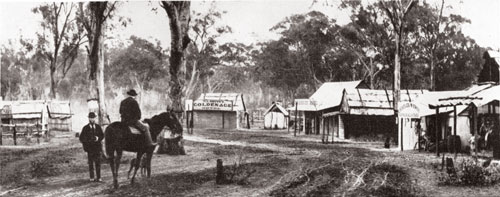

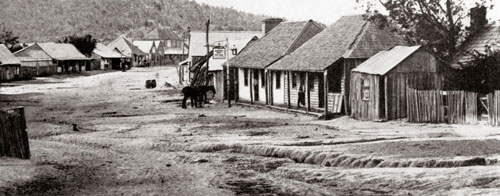

18353:

One of Gulgong's principal streets as it appeared

early in 1871. The style of building-stringy-bark

with "false-front" of

pine-was characteristic of the period.

On the extreme left we see the photographer's

wet-plate

caravan.

<

18401:

Merlin's pictures of Gulgong, Black Lead and Home

Rule are

unique in their "earliness".

We are shown Black Lead as it appeared

in its first year, the other

settlements as they stood in the first

months of their existence. Only in Australia

could the

making

of such

a record be possible.

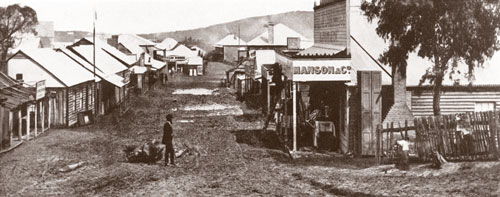

18629:

This is Clarke St., Hill End, looking south-west

from

near the present Royal Hotel, as it

appeared in the

spring of 1872, when the town was at

its

heyday. Points of interest are: Merlin's

assistant

with spare darkslide;

the signwriter at work on the signboard

outside Manson's new store; the boggy

patches in

the streets showing

the sites of old shafts; the premises

of the Australian joint Stock Bank (the two-storey

building at far end),

with Beyer's cottage just to this side

of it.

70046:

The Mudgee road passing through Tambaroora,

looking north from a -point near the

original public

school. The square brick building

at the far end is - Salkeld's

Royal Hotel; that with the twin gables

is Arthur Correy's, baker and confectioner-the

latter

is reported as having "grub

staked half the miners of the Dirt Holes".

Tombaroora (31 miles north of Hill

End) was declining in importance

by this time

(1872).

18264:

From the mining angle this is perhaps the most

interesting

of the many scores

of

similar records.

It is the

perfect documentary, showing, as

it does, all the events associated

with a gold strike. On the left

we see the red flag which the regulations

stated must

be hoisted

for

a week as soon as gold was found;

then comes the syndicate

of miners with the tallest of the

group holding the dish in which four or five

nuggets can

be seen in

the "tail";

next is the clerk from the mining

warden's office (grasping a spade

as though

he himself had found the gold);

on the right we see the butcher

included

by way of "local

colour"; as a background,

the forge (for the never-ending

tool

sharpening), and just behind

it on the right the

actual shaft and its tall whip-pole

for horse-power hoisting.

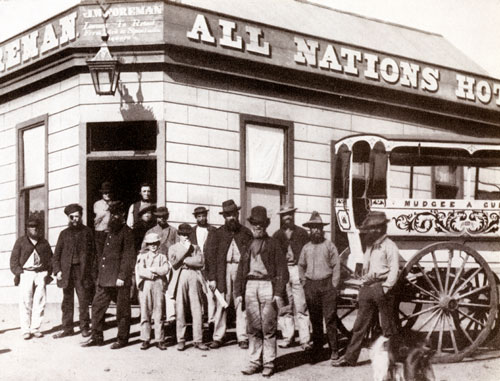

18472:

By way of contrast, this print shows a small claim

on the Gulgong field

on which

work

has just been commenced;

the reason for selection was Merlin's

fine groupings of the two sets of

figures.

18144:

Of the numerous groups of passers-by photographed

outside hotels and

business premises, this

is perhaps the best

for its admirable depiction

of a cross section of Gulgong citizens.

Here we

are introduced

to "mine host," to

an upstanding police officer,

a miner suffering from injuries

received

from a premature blast, and,

most important of all, "Paddy".

Paddy had been a circus clown

in his younger life and was

well known

for his stage attitudes, his

incomparable flow of language

and his comical "Irishisms".

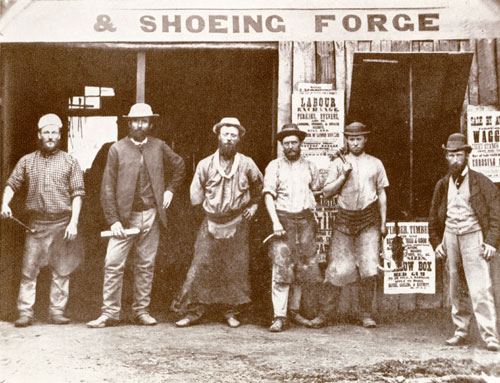

18715:

One of the best of the Hill End groups. It was

photographed

outside

Jenkyn's

shoeing forge towards

the southern

end of Clarke Street about September,

1872. The various types of workers

are represented,

while

to the right,

slightly aloof, we are introduced

to Holtermann himself. He is

to be observed

in many of

the Hill End scenes.

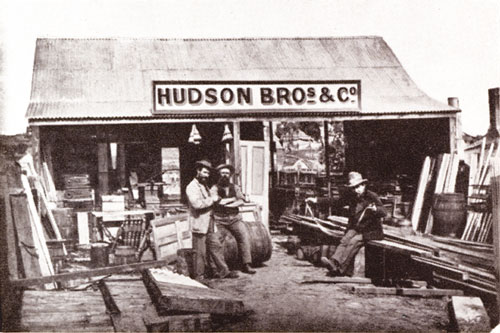

18793:

A feature of wet plate is its exceedingly fine-grain

structure;

in consequence,

provided the image

itself is sharp, enlargements

to a degree of ten or fifteen

times can readily be obtained.

This picture,we believe,

of the original

Hudson Bros is

a good example of the

possibilities in this direction.

The scene is of documentary interest as showing

the

complete stock of a typical

builder's

yard in 1872 galvanised

iron, staircase

uprights, and ready-made

doors, Australian ovens

and casks

of nails with everything

dumped just as it was

unloaded from the bullock

waggons.

18678:

This was selected for reproduction for reasons

similar

to the

preceding one. It

is so technically

excellent

and so full of trade

interest.

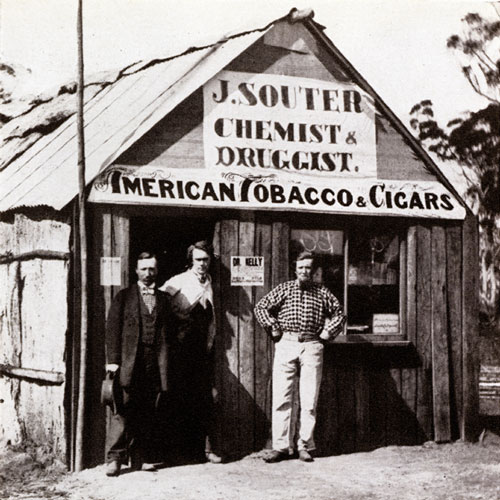

18444:

The Souters were reported the first chemists

in Gulgong, and, incidentally, their "shingle" is

still to be seen in Cleveland Street, Sydney.

They also appear to have had established the

branch in Home Rule which is here depicted. The

goldfields'

chemist shops were used as consulting rooms

by visiting doctors, and on the left we may have

the

Dr. O'Connor referred to in the left-hand notice

(as for Dr. Kelly, see below). The assistants

were not members of the Souter family.

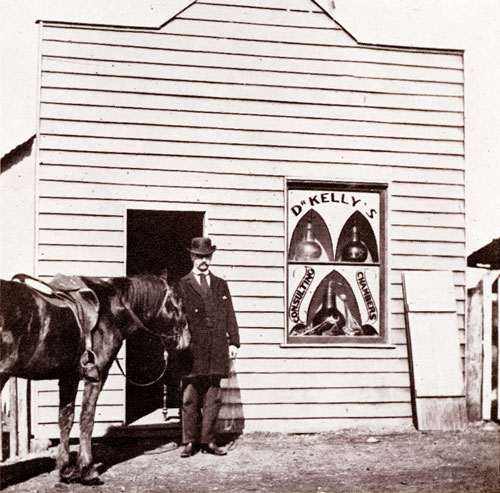

18037:

Dr. Kefly seen outside his consulting rooms

in Mayne Street, Gulgong, next door to Wood's "West

End" Stores. Of especial interest is his

window display, which comprises articulated

hands and

other bones and jars of coloured water adorned

with astrological or similar emblems.

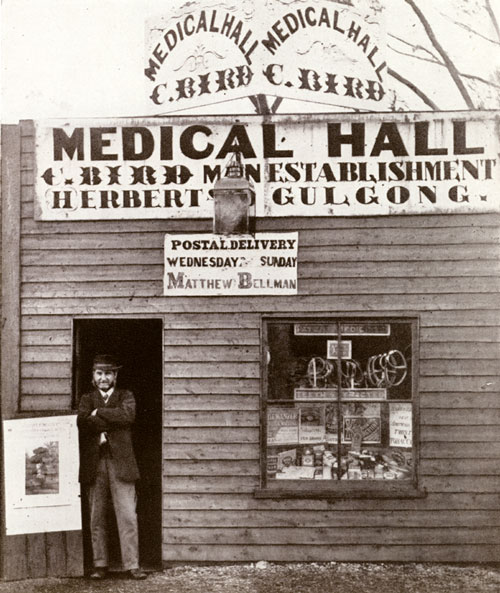

18787:

Chemist Charley Bird had two stores, one in

Gulgong and the other in Home Rule, as depicted

here

in a particularly fine technical shot. It effectively

records the contents of his display window

(trusses, cigars and sewing machines), the current

supplement

to the "Illustrated Sydney News," and

the noticeboard for the town crier, "Matthew

the Bellman". Charley, "the man with

the big ear," is recorded as one of the

town's personalities - "good company,

clever amateur actor, and a champion at all

kinds

of card

games."

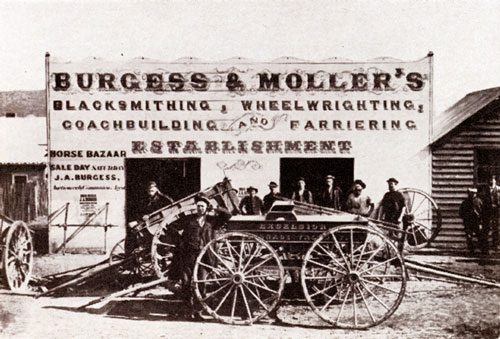

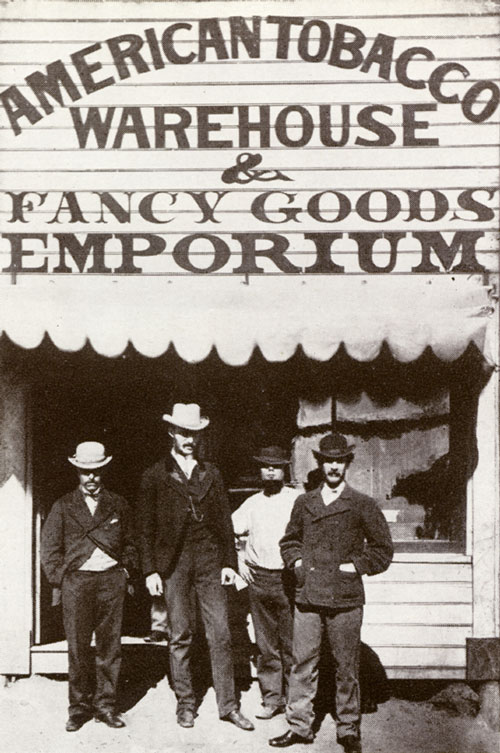

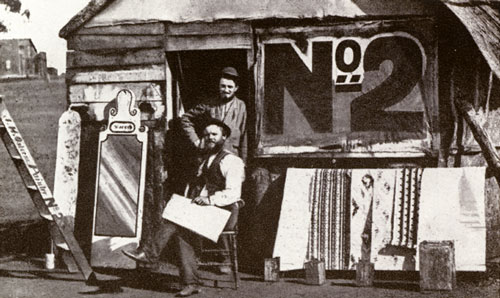

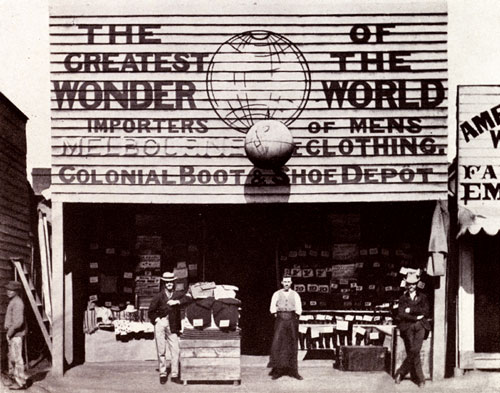

18-,

18141, 18149, 18372: To select just four from scores

of pictures of commercial establishments was a

problem, but it is hoped that these four will convey

something of the "frontier" atmosphere

that was Gulgong's in the early 'seventies.

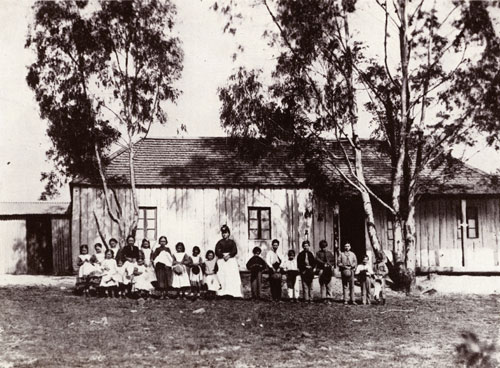

18781,

18772, 18672, 18603: Several hundreds of very informative

pictures show us the residents

of the goldfields standing outside their homes.

These four are all Hill End subjects selected

as

being somewhat more "pictorial" than

the earlier Gulgong ones, which were still in

the stringy-bark era. We are specially impressed

by

the brave showing of the pioneer women folk,

despite the incredible (to us) shortcomings in

the way

of home conveniences, to say nothing of the climatic

variations to be expected from life on an exposed

ridge three thousand feet above sea level.

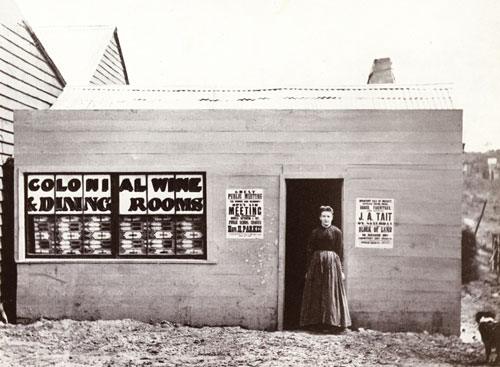

18630:

This one was selected for two reasons; first, for

the trim freshness of the premises, and, secondly,

for its obvious authenticity. The left-hand poster

refers to the visit to Hill End of the Hon. H.

Parkes and of the address which he planned for

5 p.m. on September 2nd, 1872, in the Public School

grounds.

17758:

This concluding reproduction tells its own story

of Merlin's love of the great out-doors and of

his intense artistic feeling.

return to APR introduction