|

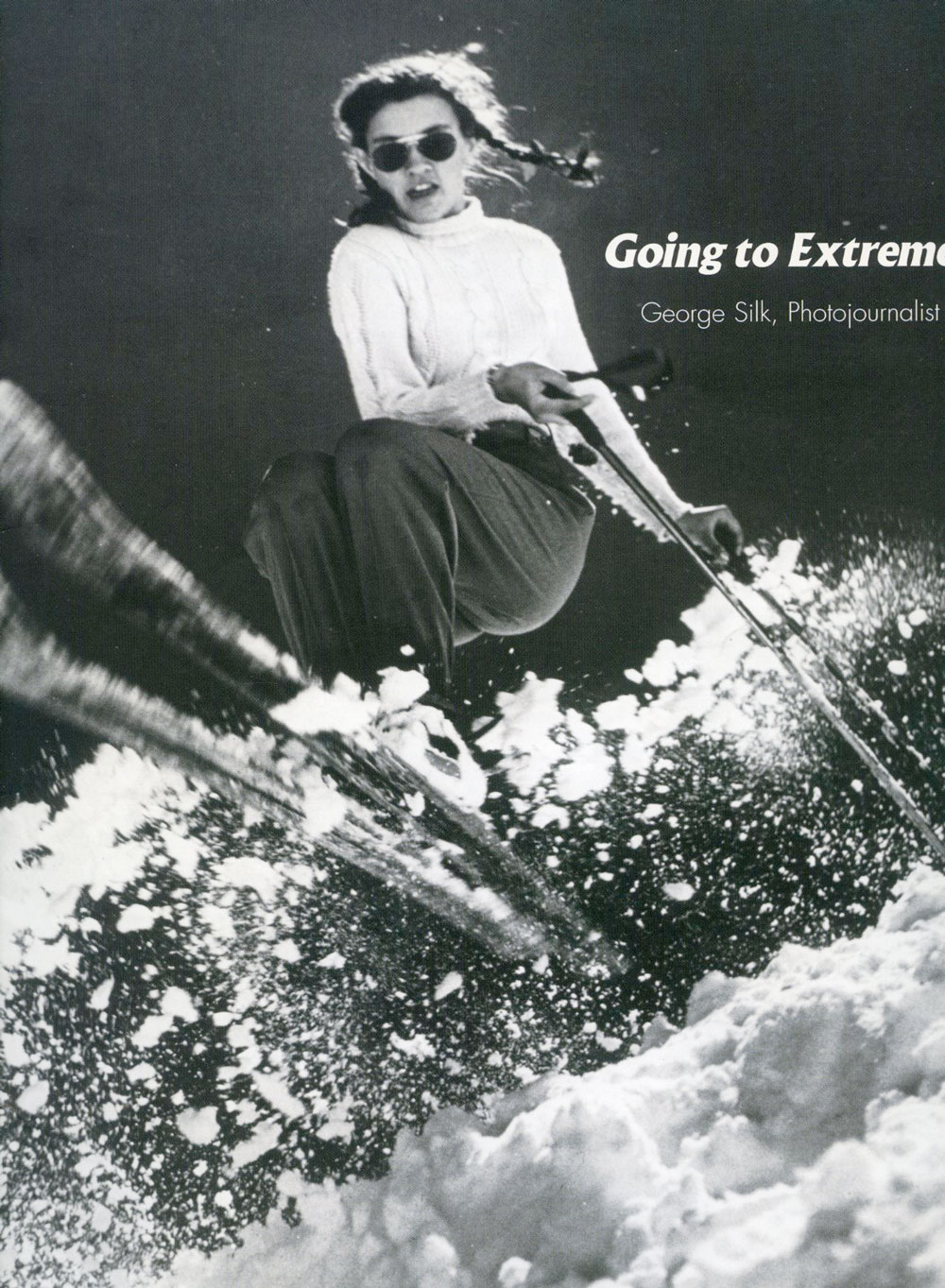

George Silk b. New Zealand 1916 to United States of America 1943. Skier Andrea Meade preparing for the 1948 Winter Olympics 1947 © Time Inc.

Going to Extremes, George Silk, Photojournalist

at the National Gallery of Australia 12 August -12 November 2000

Gael Newton

In 1939 Winston Churchill declared that Britain was at war with Germany and, as a result, governments across the British Commonwealth mobilised in support. In far away New Zealand, George Silk — then an amateur photographer working in a camera store in Auckland — clearly understood the role that photography could play as witness.

"People were interested in my pictures but I had no intention of taking photography seriously until war was declared in'39. Then it became a burning passion, a crusade to document the war. Maybe my pictures would save the world from wars, I actually thought." ( Letter by George Silk to New Zealand photo historian, John B. Turner, 26 December 1972.)

George Silk was born on the North Island of New Zealand in 1916 and raised in Auckland. School work did not interest him, but he was serious about his hobbies: model aeroplanes, climbing, fishing, sailing and, later, skiing and motor cycles. He dreamed of outdoor adventures and exploring the polar regions and remote lands. After leaving Auckland Grammar school in 1930 he worked on a farm at Taranaki on the West Coast for two years, then in a hardware store in Auckland before being offered a job with D.G. Begg Ltd, the first agency in Auckland for the modern European small format 2-1/4 square Rolleiflex, and 35mm Leica and Agfa cameras.

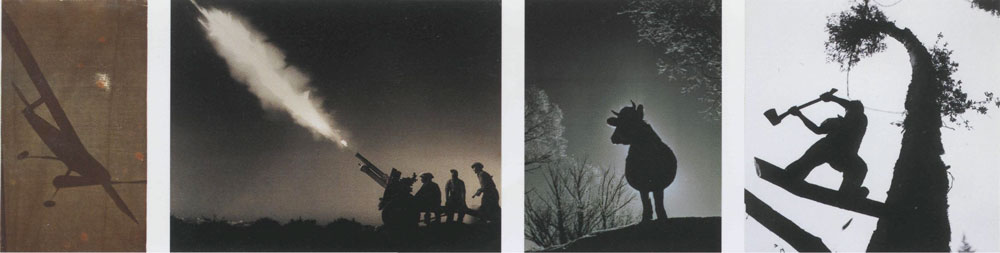

left to right: One of my models r. 1932 reproduced from Silk's earliest photographs © George Silk; New Zealand anti tank outfit firing 23 pounder gun at night against German position, Western Desert 1941 © Australian War Memorial; My favourite cow. Spring in New Zealand 1942 © George Silk; Timber felling. King Country, New Zealand 1946 © George Silk

Silk's introduction to photography was as a teenager through his sister's Box Brownie, and he began by taking pictures of his cat. He had a natural technical bent and experimented with different effects and compositions. An album of Silk's first efforts at flashlight studies shows a clever silhouette of one of his model planes hanging in front of a window blind so that it appears to be a fighter plane in a night sky. As a war photographer in the Middle East a decade later he was photographing planes at night by the flash of big guns.

In his idealism to aid the war Silk had been primed by the Documentary movement in film and photography which arose during the social consciousness of the 1930s. Silk believed that photography could affect society. Although not a professional, he was already skilled in sports and outdoor photography. Begg had encouraged Silk to become expert with the equipment in the camera store, and displayed and sold his young assistant's work — including some very large prints of yachting subjects. Through his job Silk came into contact with imported magazines and books on modern photography in advertising and magazine reportage. From this exposure he developed his own modernist style using dramatic angles — when he took up skiing he made pictures in which the skiers appear to be flying over him. He had a few pictures published in the local newspaper.

In 1939, fearing he could not be guaranteed a position as a photographer in the New Zealand military, Silk quit his homeland for Australia. From Sydney he travelled to Canberra, managed to have his portfolio of sports and outdoor photographs seen by the office of the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, and was immediately appointed to a coveted position as an official war photographer for the Australian Department of Information. From 1939 to 1942 he covered action in the Middle East, Greece, Crete and North Africa. Then, in late 1942, when Japanese forces threatened Australia and New Zealand, he was sent to New Guinea.

Silk had some pictures published in Parade, the British military magazine for the Middle East, and formed close friendships with other war photographers — in particular Damien Parer (1912-1944). While he was in the Middle East, Silk first saw issues of Life and later sent them a gentle picture of a cow. It was published in the 'Pictures to the Editors' section in February 1943.

Runners, Olympic try-outs, Palo Alto, California 1960 © Time Inc. Sweden's Olympic high jumper, Gunhild Larking, Melbourne 1956 © Time Inc.

Silk left New Guinea early in 1943 to undergo treatment for malaria and recuperate in Australia. As a war photographer his negatives and copyright belonged to the Australian government, but he managed to have some of his New Guinea pictures printed, cleared and sent to New York via a Time magazine correspondent. On 8 March 1943 Life published, as 'Picture of the Week', Silk's image of a blinded Australian infantryman in New Guinea, and the Executive Editor, Wilson Hicks, offered him a job as a war correspondent for the magazine.

In May Silk's New Guinea photographs appeared in The War in New Guinea, published in Sydney by EH. Johnston — with the blinded soldier as the frontispiece. In Sydney, Silk was one of several war photographers (including Parer) who came into conflict with the Department of Information over conditions of work and frustration at censorship which, they felt, meant that their most powerful pictures were not seen. Silk resigned from the Department of Information to join Life.

Over the next three years his pictures and photo-essays from Europe, such as the Battle of Anzio in Italy, and the allied offensive at the Roer River in Germany, were featured prominently in Life. In 1945 Silk flew over Japan in a B-29 from Iwo Jima and recorded the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He covered the Occupation of Japan that began in 1945. In 1946, after a time in New Zealand, he covered the great famine in Hunan, China. Silk remained with Life after the war and continued to be associated with stories shot under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions. In 1952 he was assigned to accompany a military expedition to establish a radio station on an ice island in the Arctic. In 1954 he covered the revolution in Guatemala and the British Empire Games in Vancouver; in 1955 he covered the Pan American Games in Mexico and, in the following year, the Olympics in Melbourne.

By the late 1950s Silk was becoming known for his sports photography involving technical innovations — beginning with a skiing story in 1958 at Sun Valley, Idaho, when he attached a wide-angle camera to his ski. In 1959, seeing the potential of the slit-cameras used at finish lines on racetracks and at athletics meets, he had a small portable version constructed. He took cameras under water and into seemingly impossible locations.

Silk's dramatic up-shot picture of a logger from 1946 as well as his picture of a child begging during the famine in China were included in the landmark travelling exhibition, The Family of Man, mounted by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955 and selected from thousands of submissions from across the world.

During the 1950s, television and improved transport facilitated the growth of national sports events, and the publisher of Life, Henry Luce, alert to the potential of sports coverage, launched Sports Illustrated in 1954. Silk was seen as a photographer who could engage a wider audience than just devotees of particular sports and, in 1956, was assigned by Life to work out of New York. He settled with his wife Margery and three children at Westport, Long Island Sound, Connecticut. With his reputation for sports photography established, Silk undertook major nature stories in the 1960s. In that decade he received several international awards.

Life was seemingly at its most glamorous, dense and colourful in the 1960s. Their experiments with colour spreads and bolder graphic layouts, however, cloaked a declining market dominance (as advertisers went over to television). Silk was in Nepal in 1972, shooting a story on the Himalayas, when he received a cable advising that Life was closing. Work as a staff photographer for Life had suited Silk; it allowed him freedom, resources and strong support services. Through the 1970s and 80s Silk continued working as a freelance photographer for various magazines, specialising in stories on ecology and the environment.

The years of war in the 1940s and the quest for photographs to fill the pages of the golden age of illustrated magazines during the post-war decades offered many young photographers the chance to make new lives in new countries. Silk, whose forebears migrated to New Zealand from Scotland and England, became an American citizen after the war. His home on Long Island Sound is far from New Zealand — and he has made only short visits there since leaving in 1939 — but the view from the large windows looking out onto the water, and following the boat races, is not unlike the beauty of Waitemata Harbour and the silvery light of the Land of the Long White Cloud.

George Silk first showed his photographs to the office of the Prime Minister in Canberra in 1939. His Department of Information photographs are held by the Australian War Memorial. It is appropriate that works representative of his international career should now be in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia.

This is his first museum retrospective.

|

|

|

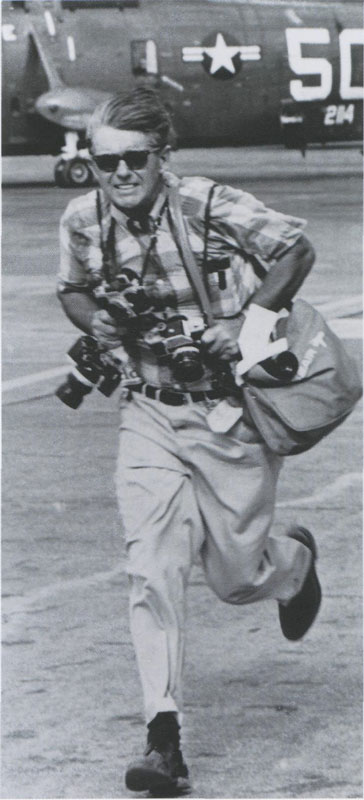

unknown photographer, George Silk, running to join flight for President L.B. Johnson's tour of 1966 collection George Silk

|

|

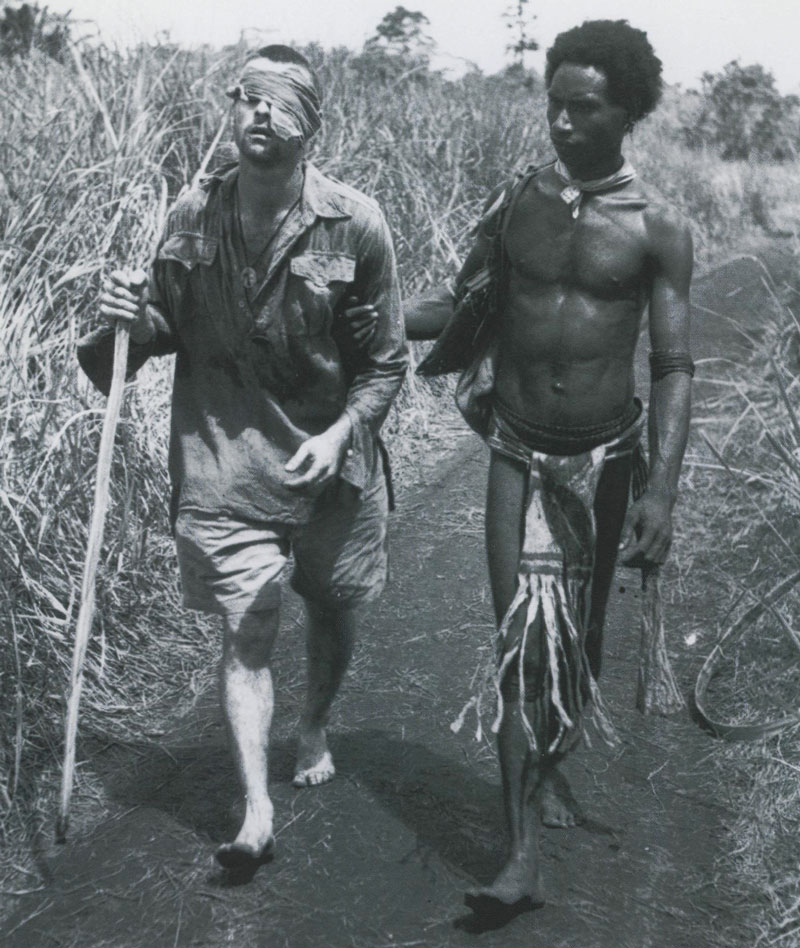

George Silk took this picture at Buna on Christmas Day 1942 after Australian and American troops had reversed the Japanese advance in New Guinea. He had arrived in New Guinea earlier in the year and was, then, the only photographer on the Buna Trail.

For Australians the image brought home the reality of war on their doorstep. It has become an iconic image of the efforts of New Guinea native volunteers, who were dubbed 'fuzzy-wuzzy angels' for their humane service to wounded Australian soldiers.

Underpinning the image is the familiar Christian iconography of the Good Samaritan aiding a wounded traveller on a lonely path. It was perhaps this broader reading which appealed to Wilson Hicks, Executive Editor of Life, who was the first to publish the photograph (8 March 1943), and led to an invitation to Silk to work for the magazine. This had been Silk's ambition since first seeing an issue of Life while covering the war in the Middle East.

Suffering from malaria, Silk left New Guinea early in 1943, never to return. His friend Damien Parer, whose film and stills of the New Guinea campaign were to secure his place as the great Australian war photographer of World War II, died in 1944. Silk's war career and friendship with Parer are documented in depth in Neil McDonald and Peter Brune's book, 200 Shots: Damien Parer and George Silk and the Australians at war in New Guinea (Allen & Unwin, 1998).

In 1993 Raphael Oimbari was awarded an OBE by the Australian government. |

Blinded soldier

(Pte George Whittington being led to an aid station by Raphael Oimbari)

1942 © Australian War Memorial |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

In the northern Spring of 1945, the U.S. Ninth Army was positioned at the Rhine opposite Diisseldorf in an offensive by the First and Ninth armies and allied forces which had begun in December 1944.

The town of Juliche had been taken when George Silk, covering the Ninth Army for Life, joined U.S. Combat Engineers on 22 February. With the cover of a night barrage and smoke screen, the Engineers had managed to install several pontoon bridges over the small Roer River, under constant shelling from German guns on the opposite bank. The Germans had released earth dams and the river was flooded.

Between 10pm on 22 February and 8am the following morning Silk shot the story. As he crossed to the east bank on one of the pontoons he took the picture of a G.I. killed ahead of him by mortar-shell fragments.

This image appeared in Life, 12 March 1945, in a story, 'The Allies drive for the Rhine', which included a sequence of images of the pontoon bridge breaking apart as Medics tried to retrieve the body of the dead G.I. |

| Dead American soldier on pontoon bridge across the Roer River, Germany 1945 © Time Inc. |

|

|

Halloween 1960, type C colour photographs printed late © Time Inc.

George Silk became interested in the aesthetic possibilities of the distortions produced in race-finish cameras when he covered the 1959 Kentucky Derby. Photo-timers had been in use since 1951 for athletics, and at the Olympics in 1952 and 1956. Photographs made in these cameras stretched or foreshortened the figures leaving only a tiny vertical slit of the film in focus at the exact finish line. Silk had a portable version made, using a phonograph motor to drive the film past the slit which replaced a conventional shutter.

The image produced by the slit camera turned the hammer thrower at the U.S. try-outs into a cartoon strongman, but also conveyed the intensely private moment of the athlete straining in his endeavour to win. The slit camera picture were quite abstract — Silk said: 'I was thrilled when the prints showed strength, speed, design — originality.' For the try-outs story in Life, 18 July 1960, Managing Editor, Edward K. Thompson ran the slit camera images as large illustrations alongside straight shots of the winners. |

|

|

| |

|

Hammer thrower, U.S. track team Olympic try-outs, Palo Alto, California 1960 © Time Inc. |

Silk had first tried out his slit camera by photographing his children and their friends dressed in Halloween costumes. A sequence of these colour images appeared as 'Spectacle of Spooks to be wary of on Halloween' in Life, 31 October 1960 — Executive Editor, Bernard Quint had the images cut and duplicated into wild graphic patterns worthy of a technicolour fantasy by Walt Disney.

Both these stories were radically different to the usual narrative sequence of photo-essays. A new look with more colour spreads and graphic layouts was part of a re-design of Life that Quint and Thompson introduced in 1960-61.

|

|

|

| |

|

Halloween layout in Life, 31 October 1960 © Time Inc. |

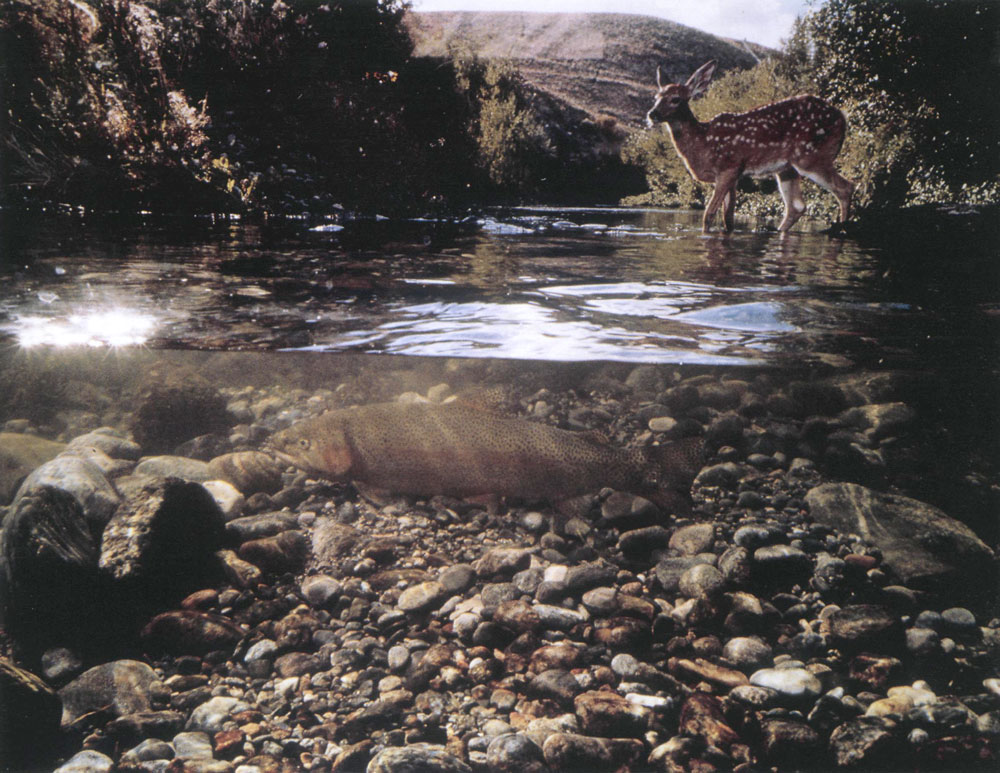

Fawn and rainbow trout, tributary of the Madison River, Montana 1961 dye transfer colour photograph printed later © George Silk.

A variant of this picture appeared in George Silk's photo-essay for Life, 'Wild Creatures of America', in December 1961. The overall theme of that special double issue of the magazine was 'Our Splendid Outdoors'. Silk travelled 11,000 miles across America over four months on the assignment.

To make this picture he used his knowledge of the way spawning trout react when disturbed: '... I moved some rocks to make the water flow in a way attractive to spawning trout.' Silk waited more than a week for all the elements to come together. To show the trout and fawn together he enclosed his camera in a large glass box submerged half-in and half-our of the water and set the exposure from some distance away by a cable release.

'Perfect ten point landing, Kathy Flicker, Dillon Gym Pool, Princeton University 1962 © Time Inc.

This image was the centrepiece of George Silk's story in Life, 20 April 1962, and showed three successive stages of a dive by the 14-year-old national champion Kathy Flicker — which the copywriter declared was surely worthy of a 'perfect ten' score.

The assignment was shot in one afternoon. Silk had the water level lowered to half-way down a trainer's observation window in the side of the pool; he had six flash units set up to record Kathy's entry into the water — knowing that his timing had to match the entry exactly.

Spring-board, or 'art' diving was introduced into the Olympics in 1908 for men, and in 1912 for women. By the 1920s and 30s images of beautiful divers in mid-flight symbolised the new age of speed and unisex super-human sporting prowess.

Silk's image takes its place in a lineage of famous underwater shots — amongst those by the German photographer and film maker Leni Riefenstahl for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, and the wondrous frozen and multi-flash high-speed studies of divers by Dr Harold Edgerton, the pioneer of electronic flash photography in the 1930s whose work was featured in Life.

Many later sports photographers have made images of divers in and under water, but Silk's black and white image remains a classic. Although Kathy Flicker did nor become an Olympic champion, in the photograph she is immortalised, half-in, half-out of the pool.

Gretel and Weatherly, off Newport, America's Cup trials 1962 dye transfer colour photograph printed later © George Silk

|

|

In 1962 Gretel was the first Australian yacht to challenge the New York Yacht Club for the famed America's Cup. The defenders in Weatherly won the Cup.

George Silk's image of the two boats captures the audacity and excitement of the 1962 Cup, but also makes the boats appear abstract and magical as in a children's book illustration.

This picture, although a personal favourite of the photographer, was not amongst the images reproduced in Silk's award-winning story on the America's Cup, 'Cutting the Waves for a Classic Cup', published in Life in August 1962, for which Silk wrote the text. The Life story was included in the definitive exhibition, The Photo Essay, at the Museum of Modern Art in 1966.

The 1962 America's Cup essay established Silk as a photographer with the ability to sweep the viewer into the heart of the action and to share the passion of the 'yachties'. |

unknown photographer

George Silk sailing on Waitemata Harbour c.1935

collection George Silk |

|

Unless otherwise indicated all works illustrated are gelatin silver photographs

and from the collection of the National Gallery of Australia. |

Going to Extremes: George Silk, Photojournalist was an exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia 12 August -12 November 2000

The exhibition was organised at the National Gallery of Australia by Gael Newton, then Senior Curator of Photography, assisted by Anne O'Hehir, Assistant Curator of Photography. The exhibition could not have been realised without the active assistance of George and Margery Silk, and Georgiana Silk, Connecticut, USA, and was made possible through sponsorship from Time Inc., New York, and Nikon/Maxwell Optical Industries, Sydney.

|